|

FEATURES

Tope and topos | China Heritage Quarterly

Tope and topos

The Leifeng Pagoda and the Discourse of the Demonic

Eugene Y. Wang 汪悅進

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Professor of Asian Art

Harvard University

Eugene Wang's important study of Leifeng Pagoda on West Lake expands our consideration of the Ten Scenes of West Lake—and what the Republican-era writer Lu Xun decried as the 'ten scenes syndrome' in China, as well as adding nuance to the history of the White Snake and the symbolism surrounding that now-perennial story.

This essay originally appeared in Writing and Materiality in China: Essays in Honor of Patrick Hanan, Judith T. Zeitlin, Lydia H. Liu with Ellen Widmer, eds, (Harvard-Yenching Monograph Series, 58), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2003. It is reprinted with the kind permission of the author with minor stylistic changes, and is presented in three parts:

A pdf version of this article can be accessed here. For more downloadable PDF-format research papers by Professor Wang, click here.— The Editor

Lu Xun's Visionary Worlds: Ruins Haunted by Serpentine Spirits

Lu Xun's loathing of the Leifeng Pagoda, fully articulated in his first essay on the collapse of the pagoda, is easily recognizable. What is less acknowledged is the role of the site in the making of his fiercely imaginary world. The contradiction between his resentment of the 'tottering' pagoda and his attraction to ruins is in fact less self-evident than it first appears. The pagoda is no more than a locus and an analogue that allows him to string together often related thoughts into a coherent discursive ground. Both of his essays on the pagoda were written in the distinct genre of 'miscellaneous writings' or 'impromptu reflections'. Such essays tend to respond to a current event or topic. The discussion usually extends beyond the 'immediate circumstances to their larger significance and, in the case of Lu Xun, the character of Chinese culture. Central to such an excursion is an organizing image or analogue. Foreigners' praise of a Chinese banquet provoked his reflections on the Chinese propensity to feast their conquerors and one another, reflections that brought him to his graphic claim that 'China is in reality no more than a kitchen for preparing these feasts of human flesh.' In this case, the banquet was the organizing motif.[105] The pagoda ruin is another such enabling analogue. It provided him with a platform to address two seemingly unrelated issues: the depressing cultural stasis of China and the dialectic between destruction and construction. Two attributes of the Leifeng Pagoda—that it is one of the Ten Views of West Lake and that it exists as a ruin—permit Lu Xun's reflection. He first took up the public regret over the collapse of the pagoda for destroying the wholeness of the Ten Views of West Lake. To Lu Xun, the dogmatic clinging to this arbitrary construct, with its falsifying wholeness, betrayed a cultural resistance to change. The Ten Views of West Lake embody a cultural landscape of stasis. Ruin, the second motif he extrapolated from the Leifeng Pagoda site, provoked thoughts on destruction and construction, first in the physical or material sense, then in the symbolic or metaphorical sense.

Men like Rousseau, Stirner, Nietzsche, Tolstoy or Ibsen are, in Brandes' words, 'destroyers of old tracks'. Actually they not only destroy but blaze a trail and lead a charge, sweeping aside all the old tracks, whether whole rails or fragments, that get in men's way, but making no attempt to pick up any scrap iron or ancient bricks to smuggle home in order to sell them later to second-hand dealers.[106]

The motif of symbolic destruction soon leads to the topic of drama and connects with the first motif of Ten Views of West Lake:

All the world is a stage: tragedy shows what is worthwhile in life is shattered, comedy shows how what is worthless is torn to pieces, and satire is a simplified form of comedy. Yet passion and humor alike are foes of this ten-sight disease, for both of them are destructive although they destroy different things. As long as China suffers from this disease, we shall have no madmen like Rousseau, and not a single great dramatist or satiric poet either. All China will have will be characters in a comedy, or in something which is neither comedy nor tragedy, a life spent among the ten sights which are modeled each on the other, in which everyone suffers from the ten-sight disease. (Selected Works, p.97; italics added)

The theme of ruins allowed him to attack both the static traditionalism that resisted change and the pervasive pettiness of looting public properties. On the one hand, he envisioned China as a colossal ruin whose inhabitants are perennially given to mending the decaying structure rather than reconstructing a new state. Foreign invasions and internal unrest bring about 'a brief commotion', only to be followed by the patching up of 'the old traditions... amid the ruins.' 'What is distressing is not the ruins, but the fact that the old traditions are being patched up over the ruins. We want wreckers who will bring about reforms' (Selected Works, p.99). The destruction Lu hailed is an overhauling of the entire old system, not the petty pilfering of public properties. To Lu, 'the theft of bricks from the Leifeng Pagoda', which caused its collapse, was alarming not in and of itsel£ but because it betrayed a deeper social malaise that 'simply leaves ruins behind; it has nothing to do with construction.' (p.99)

What Lu Xun got out of the Leifeng Pagoda as an analogue in the second essay demonstrates the workings of a topographic site as a topic. The locus generates arguments and brings out hidden relationships between domains of experiences that would otherwise remain unrelated to each other. As a consummate man of letters, Lu Xun worked on and through an imaginary ruin on which he launched his own symbolic destruction and construction all at once.

This is just part of the story. There is more to ruins and the Leifeng Pagoda than what Lu Xun articulated here. Granted, he identified Nietzsche and company as the forces of symbolic destruction much needed in China. But that remains a theoretical abstraction and program. It has yet to crystallize into visual images and tropes that are the stuff of Lu's mind and sustain the intensity of his thinking. The question then becomes: As he yearned for drama, what kind of symbolic drama did he envision?

The two essays on the Leifeng Pagoda themselves offer clues. The first celebrates the collapse of the pagoda as an oppressive symbol in the context of the White Snake; the second calls for a drama of destruction and construction. Is there a connection between the two? Is drama the thread that links the two essays and divulges Lu Xun's imaginary site? There appears to be more to the Leifeng Pagoda ruin in Lu Xun's mind than his essays spells out. We should not let Lu Xun's avowed aversion toward the Leifeng Pagoda beguile us into thinking that this is his attitude toward the site. That site, invigorated by the White Snake drama, is the imaginary stage on which Lu Xun's envisioned drama unfolds.

The paradigm is set up in his 'From Hundred Plant Garden to Three Flavor Study', an account of his childhood. The essay is topographically structured; it turns on a binary opposition between the Hundred Plant Garden, the deserted backyard of his family estate, and the Three Flavor Study, the private school in which he was sent to study. The garden is an imaginary realm open to the wonders of nature and where fantasies about the supernatural could be sustained; the school is a confining place of rigid discipline and Confucian indoctrination where fantasies are banished. The garden is suffused with the imaginary presence of the 'Beautiful Woman Snake—a creature with a human head and the body of a snake', who, as Lu is told by his nanny, once nearly seduced a young scholar, and would have succeeded had it not been for the intervention of an old monk, who detected 'an evil influence on [the young man's] face'. The young Lu Xun is therefore always in rapt anticipation, mindful of the 'beautiful snake woman,' when he 'walks to the edge of the long grass in Hundred Plant Garden.' In contrast, the Three Flavor Study is no place for the fantastic and the monstrous. The young Lu Xun, full of curiosity about the supernatural, visibly displeased his teacher when Lu asked about the nature of a legendary strange insect called 'Strange Indeed' (guaizai 怪哉) associated with Dongfang Shuo 東方朔, an ancient magician.[107]

It is significant that Lu Xun mapped the White Snake story to his childhood memory of the deserted garden of his family home. A ruin haunted by a serpentine spirit was the symbolic topography on which many of Lu's imaginary scenarios unfolded. His fascination with the White Snake lore underlay his resentment of the Leifeng Pagoda, but the imaginary site of the pagoda, or a ruin, haunted by a serpentine spirit, is precisely the stage for his imaginary drama. In 'Dead Fire', published in April 1925, the speaker envisions a surreal spectacle: 'From my body wreathed a coil of black smoke, which reared up like a wire snake.'(p.108) In 'Stray Thoughts,' which appeared in May 1925, three months after he wrote the second essay on the Leifeng Pagoda, Lu urged: 'Whatever you love—food, the opposite sex, your country, the nation, mankind—you can only hope to win if you cling to it like a poisonous snake, seize hold of it like an avenging spirit.'(p.109) In 'The Good Hell That Was Lost,' which came out in June 1925, the speaker 'dreamed [he] was lying in bed in the wilderness beside hell. The deep yet orderly wailing of all the ghosts blended with the roar of flames, the seething of oil and the clashing of iron prongs to make one vast, intoxicating harmony, proclaiming to all three worlds the peace of the lower realm.' He is then told that this 'good hell' is lost to man who 'wielded absolute power over hell… reconstructed the ruins. ...At once the mandrake flowers withered.'(p.110) In 'Tomb Stele Inscription,' also dating to June 1925, Lu Xun wrote:

I dreamed of myself standing in front of a tomb stela, reading the inscription. The tombstone seemed to have been made of a sandstone, moldering substantially, mossgrown, leaving only limited words— ...There was a wandering spirit, metamorphosed into a snake, with venomous teeth in its mouth. It does not bite human beings; instead, it gnawed into its own body until it perished. …Go away! …I circled around the stela, and saw a forlorn tomb in barren ruins. From its opening, I saw a corpse, its chest and back all deteriorating with no heart and liver in its body. ...I was about to leave. The corpse sat up, its lip unmoving, but said—

'When I turn into ashes, you shall see my smile.'[p.111]

In 'Regret for the Past,' written in October 1925, Lu Xun envisioned a glimmer of hope in a landscape of despair:

There are many ways open to me, and I must take one of them because I am still living. I still don't know, though, how to take the first step. Sometimes the road seems like a great, grey serpent, writhing and darting at me. I wait and wait and watch it approach, but it always disappears suddenly in the darkness.[p.112]

Lu Xun's dramatic vision of the spirit-haunted ruin was rooted in a memory of the village opera he saw in his childhood in his native place, Shaoxing. Foremost in the repertoire was the Mulianxi 目連戲, or Dramatic Cycle of the Tale of Mulian (Maudgalyayana). Based on a medieval Chinese Buddhist tale, the play shows the descent of Mulian, one of the Buddha's disciples, into hell to search and eventually rescue his mother who is condemned there for her sins. The stage playas Lu Xun saw it as a child typically began at dusk and ended at dawn of the next day.(p.113) The cycle opens with a ritual ceremony of 'Summoning of the Spirits,' 'those who had died unnatural deaths':

This ceremony signified that the manifold lonely ghosts and avenging spirits had now come with the ghostly king and his ghostly soldiers to watch the performance with the rest of us. There was no need to worry, though. These ghosts were on their best behavior, and would not make the least trouble all this night. So the opera started and slowly unfolded, the human beings interspersed with apparitions: the ghost who died by fire, the ghost who was drowned, the one who expired in an examination cell, the one eaten by a tiger.[p.114]

This is followed first by a 'Hanging Man Dance' and then a 'Hanging Woman Dance,' which features a female ghost who complains about the miserable life that led her to suicide. Now she seeks revenge. The female ghost in particular fascinated Lu Xun. Many years later he recalled her terrible beauty with fondness.(p.115)

Two qualities in Lu Xun's memory of the village opera informed his dramatic sensibility. First, it is inhabited by ghosts and spirits, in particular, female ones. Second, it has a twilight or hazy mood. Not only was the 'Summoning of the Spirits' enacted at the sunset, but the haziness exists in Lu Xun's mind in the form of recollection: 'the hazy, moonlit outlines of a temporary stage erected on the empty strand between the village and the river ...the faintly discernible abode of Daoist Immortals, bathed in a halo of torchlight that shrouded it like the sunset glow of evening.'(p.116) These twin qualities—the twilight mood and the spectral energy—are precisely what the Leifeng Pagoda evoked: the view of the pagoda at sunset and the romance of the White Snake woman trapped under it. Indeed, Lu Xun was unimpressed with the sight of the 'tottering structure standing out between the lake and the hills, with the setting sun gilding its surroundings,' and he had no patience for the 'Ten Views syndrome'. What troubled him was the stale view of the 'Pagoda at Sunset' divorced from the drama of the White Snake spirit. His two essays are attempts to restore drama, in its different senses, to the otherwise stagnant site. In other words, Lu Xun reconstituted the traditional Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow and refined it as a modernist topography.

A set of circumstances combined to intensify his vision. On April 8, 1924, five months before the Leifeng Pagoda collapsed and six months before he wrote his first essay on the subject, Lu Xun bought Symbolism of Depression, by Kuriyagawa Hakuson (1880-1923), a Japanese art critic. Five months later, he translated the book. The book apparently excited him, for it took him just twenty-one days to finish the project. He began translating another book by the same author, Out of the Ivory Tower, in late 1924 and finished it on February 18, 1925. Meanwhile, he was teaching at universities in Beijing, and he lectured on the Symbolism of Depression and made mimeographed copies of his galley proofs and distributed them as assigned reading.[117]

Kuriyagawa Hakuson was a prominent art critic in Japan in the early twentieth century. A graduate of Tokyo Imperial University, he continued his studies in the United States. He returned to Japan and taught at universities in Tokyo, Kyoto, and various places. He died in the 1923 Tokyo earthquake. The Symbolism of Depression was retrieved, as a friend recalled, 'from the ruins of the master's residence'.(p.118) Kuriyagawa was a follower of Bergson and Freud. His position, as spelled out in the two books that Lu Xun translated, is a rehash of Bergson and Freud: the ultimate motor driving artistic creation is the melancholy resulting from depression and oppression of the life force; art is capable of creating a world of individuality with total imaginative freedom; art can project mental images through concrete 'symbols', and so forth.

Kuriyagawa's style is fierce, and his social criticisms scathing. From a radical stance, he relentlessly lampooned the problems that plagued Japanese society and the Japanese mentality. In this, he was not unlike Lu Xun. Kuriyagawa's appeal for Lu Xun should be obvious. From Kuriyagawa, Lu Xun acquired the Freudian calculus—the valorization of desire, the affirmation of the energy of the libido, and the awareness of its repression as the ultimate source of the eruptive 'life force'.(p.119) This new language gives his old sensibility—molded out of his rural upbringing—a new spin. It releases the demonic forces: the female ghost of the village opera, the spirits that populate the Buddhist hell, the demonic energy associated with the White Snake woman, and the monstrous union between a mortal being and a supernormal creature, and so on took on a new life in the theoretical light of modernism. The ruin of the Leifeng Pagoda lent itself as a primal site for Lu Xun to play out his modernist vision.

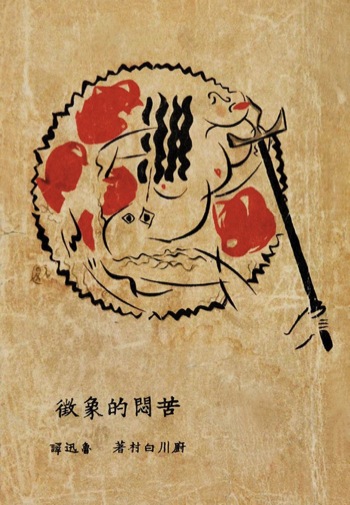

Fig.14 Tao Yuanqing, cover design for Lu Xun, trans., Kumon no shocho; Kumen de xiangzheng (Symbolism of depression) by Kuriyagawa Hakuson (1880-1923) (Shanghai: Weimingshe, 1924).

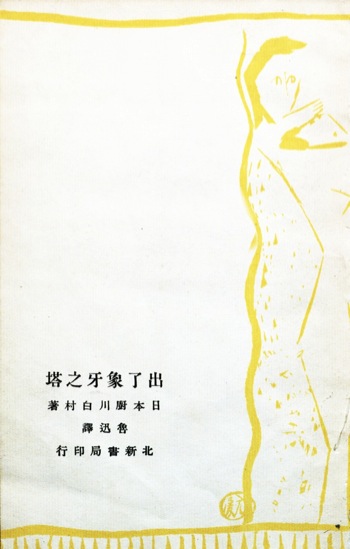

Fig.15 Tao Yuanqing, cover design for Lu Xun, trans., Zoge no to o dete; Chule xiangya zhi ta (Out of the

ivory tower) by Kuriyagawa Hakuson (1880-1923); (Shanghai: Weimingshe, 1924).

More specifically, Kuriyagawa was one of the first Asian scholars to introduce Keats's Lamia story to Asia and to note its similarity to the Chinese White Snake lore and its derivative treatment in Japan. Many of his works were translated into Chinese in the 1920s by several distinguished scholars, including Feng Zikai 豐子愷 and others.(p.120) As someone who consistently valorized sexual desire as the creative force, he was drawn to what he called 'serpentine sexuality', and he praised the sympathetic treatment of snake lore by both Keats and Theophile Gautier, French romantic author of La Morte amoreuse. 'Instead of loathing the demonic woman', he wrote, 'they make one feel what is ineffably beautiful, a quality that can be characterized as chillingly bewitching.' In comparison, he found the Japanese treatment of the matter wanting.(p.121) Kuriyagawa here reinforced a nearly forgotten traditional aesthetic category: 'chillingly bewitching', sai'en 悽豔 (Ch. qiyan). It describes a curiously paradoxical effect, evocative at once of a chilly, mournful desolation and an irresistible enchantment—the twin qualities of the darkly suggestive landscape of the Leifeng Pagoda with its serpentine enchantress.

Lu Xun's life in the 1920s was, deeply caught up with pagodas. From August 2, 1923, to May 25, 1924, he lived in a neighborhood in Beijing called 'Brick Pagoda Alley'. On April 17, 1924, on a lecture trip to Xi'an, he visited the Great Goose Pagoda of the Daci'en 大慈恩 Temple. The day before he wrote 'On the Collapse of the Leifeng Ta', he bought Kuriyagawa's book Out of the Ivory Tower, whose title contains the kanji-character to 塔 (ta in Chinese; 'pagoda'). He was to live with this book for an extended period as he proceeded to translate it.(p.121) These circumstances may have cued his writing on the topic of pagodas.

Pagodas and women, unrelated to each other except in the Leifeng Pagoda lore, came to a head in the 1920s, a period that saw the surge of the women's liberation movement. Appointed to the faculty of Beijing Women's Normal College in July 1923, Lu Xun was actively involved in the women's cause. In April 1925, two months after Lu Xun wrote the second essay on the Leifeng pagoda, a heinous event rocked the country. Four female college students visiting an 'ancient site', the Iron Pagoda at Kaifeng, were brutally raped by six soldiers. After this abominable act, the brutes ripped strips from each of the women's skirts as 'souvenirs' and hung their clothes on the top of the pagoda. The women had to endure further humiliation at the hands of their school's administration. Fearful that the scandal might tarnish the school's reputation, they chose to silence the victims' voices and publicly denied the incident. The four women committed suicide. Zhao Yintang (1893-?), a lecturer in Chinese at Beijing Normal University, wrote on the event with anguished sarcasm:

Who asked them [the women] to visit the Iron Pagoda in that desolate place? The pagoda is indeed an extremely famous ancient ruin. Only the governor should be allowed to climb up and view the scenery; only celebrities and scholars should be allowed to inscribe their names there. Or to put it in a less dignified tone, only male students should be allowed to climb to the top to yell and scream. These women—what right did they have to visit [this site]? Unqualified with this right, they went anyway. Wasn't that indecorous? Shouldn't they die?[123]

The incident also enraged Lu Xun (LXQJ, 7:274). Indeed, it occurred in the wake of Lu Xun's two essays on the Leifeng Pagoda, yet it epitomized an enduring social reality in which the weight of traditional values kept crushing innocent victims, particularly women. It dramatized the pagoda—a signpost of tradition in modern times—as the oppressive symbol and symbolized the social injustice women had to bear. The tragedy at the Iron Pagoda is almost an uncanny modern re-enactment of the Leifeng Pagoda and its subjugation of the White Snake woman. It testifies to the relevance of Lu Xun's two essays and makes Lu Xun's loathing of the pagoda as an oppressive presence and his sympathy with the White Snake woman all the more compelling.

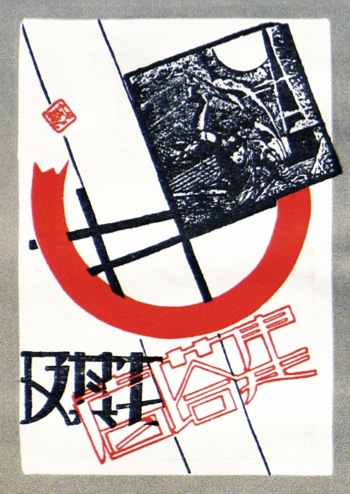

Fig.16 Li Jiqing, cover design for Tai Jingnong, Jiantazhe (Pagoda builder). 1928. (Beiping: Weiming she, 1930). After Tai Jingnong, Jiantazhe (Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1984).

Much as the landscape of the pagoda ruin served as a symbolic topography for modernist writers such as Lu Xun and Xu Zhimo and gave shape to their discursive energy and imaginary universe, their work in turn inspired visual constructs. Lu's vision found its visualizer in an able young artist named Tao Yuanqing 陶元慶 (1892-1929), also a native of Shaoxing. Tao's cover design for Lu Xun's translation of Symbol of Depression shows a nude female figure imprisoned in a claustrophobic circle, wriggling among four crimson patches of monsters threatening to gnaw into her. With her hands seemingly entangled, the woman holds a trident with one foot, whose prongs touch her lifted chin. [Fig.14] Tao's design for the cover of Out of the Ivory Tower again features a female nude, somewhat startled, standing against a wavy and wriggling line.[Fig.15] It may be far-fetched to take the serpentine line in both cover designs as a coded visual allusion to the White Snake woman, but the evocation of oppression, desire, and destruction in the first design and the connection between woman and pagoda in the second are all very suggestive. Lu Xun's dramatic vision of the Leifeng Pagoda is precisely about these diverse impulses.

Lu Xun's imaginary ruins, haunted sites invigorated with supernatural forces, became a topos widely shared by his contemporaries. It prompted a group of young followers of Lu Xun in the 1920s and 1930s to cast their mournful eyes to their own native places. They evoke ruins of the past and aspire toward the landmarks heralding the future. Among the group was Tai Jingnong 臺靜農, whose short story 'Pagoda Builder' relates the tale of an imprisoned young woman put to death by her oppressors. The thin narrative is premised on the conviction that 'our pagoda is not built on soil and rocks, but on the foundation of our blood-congealed blocks.'(p.124) The 'Pagoda Builder' became the title for the author's collection of stories, published in 1928. Its cover, designed by Li Jiqing, shows a leftward-tilting grid of dark lines crossed by a red crescent band. An intersection generates a square in which a mason—apparently the 'Pagoda Builder'—hammers a drill rod into a stone block. A tall tower soars above clouds, set against the sun. The more realistic scene inside the box thus thematically echoes the abstract coordinates outside it: illuminating the grid as a soaring structure in the making and the red band as a vague evocation of the sun, and by extension, a hopeful future. Consistent with the geometric mood, the characters of the book title are rendered in 'art script' (meishuzi 美術字), as opposed to the traditional calligraphic scripts, to register a touch of modernism. In color scheme, the design thrives on a sharp contrast between red and black, set against a white background.(Fig.16) It is a modernist reworking of the Pagoda in Evening Glow: not only is the soaring structure, explicitly mentioned in the title as a ta (pagoda), envisioned as an obelisk with its foreign—hence, for the Chinese at the time, modernist—overtones, the sun—presumably anything but a setting sun—evokes blood, sacrifice, and passion, as evidenced in Tai's narrative. This futuristic-utopian pictorial construct brings this story of the Leifeng Pagoda to a close. The pagoda site, which began innocently as no more than a circumstantially rooted monument, ends up becoming an enduring signpost in the Chinese mental universe and a topos that generated an ever-increasing body of writing for centuries.

Previous

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes to Part III:

[105] David E. Pollard, 'Lu Xun's Zawen' in Lu Xun and His Legacy, ed. Leo Ou-fan Lee (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), p. 65. I adopt Pollard's suggestion of 'analogue,' which is particularly revealing about Lu Xun's discursive habits.

[106] Lu Xun, 'More Thoughts on the Collapse of Leifeng Pagoda,' in Selected

Works of Lu Hsun, p. 96.

[107] Lu Xun, 'From Hundred Plant Garden to Three Flavor Study,' in Selected Works, I: 387-93.

[108] Selected Works, I: 340.

[109] LXQJ, 3: 49; trans. Selected Works, 2: 143-44.

[110] LXQJ, 2: 199-200; trans. Selected Works, I: 343-44.

[111] LXQJ, 2: 202-3.

[112] LXQJ, 2: 129; trans. Selected Works, 1:260

[113] Zhou Zuoren, 'On the Miracle Play of Mulian,' in Tanlongji 談龍記 (Speaking of dragons: essays) (Shanghai: 1927), 140; Tsi-an Hsia, 'Aspects of the Power of

Darkness in Lu Hsiin,' in idem, The Gate of Darkness: Studies on the Leftist Literary

Movement in China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968), pp.156-57.

[114] Lu Xun, Selected Works, I : 435.

[115] Ibid., pp.437-38

[116] Lu Xun, 'Village Opera,' in William A. Lydl, trans., Diary of a Madman and

Other Stories (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990), pp.210-12.

[117] Feng Zhi, Lu Xun huiyi lu (Memoir of Lu Xun) (Shanghai: Wenyi chubanshe, 1978), I: 84.

[118] Lu Xun 魯迅, Lu Xun quanji 魯迅全集 (Complete works of Lu Xun) (Shanghai: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1973), 13: 129.

[119] LXQJ, 10: 231-35.

[120] Lu Xun was not the only translator of Kuriyagawa's Symbolism of Depression. Feng Zikai's translation appeared about the same time as Lu's, in March 1925. See Feng Zikai 豐子愷, trans. Kumen de xiangzheng 苦悶的象征 (Symbolism of depression) (Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1925).

[121] Kuriyagawa Hakuson, 'The Western Serpentine Sexuality,' in Lü Jiao 綠蕉 and Liu Dajie [劉]大杰, trans., Zouxiang shizi jietou 走向十字街頭 (Walking toward the crossroads) (Shanghai: Qizhi shuju, 1928).

122. The translation was finished on Feb. 18, 1925.

[123] The Women's Weekly, supplement of Jingbao, no. 21, May 6, 1925.

[124] Tai Jingnong 臺靜農, Jiantazhe 建塔者 (Pagoda builder), 1st ed. 1928 (Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1984), pp.121-25.

|