|

FEATURES

Tope and topos | China Heritage Quarterly

Tope and topos

The Leifeng Pagoda and the Discourse of the Demonic

Eugene Y. Wang 汪悅進

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Professor of Asian Art

Harvard University

Eugene Wang's important study of Leifeng Pagoda on West Lake expands our consideration of the Ten Scenes of West Lake—and what the Republican-era writer Lu Xun decried as the 'ten scenes syndrome' in China, as well as adding nuance to the history of the White Snake and the symbolism surrounding that now-perennial story.

This essay originally appeared in Writing and Materiality in China: Essays in Honor of Patrick Hanan, Judith T. Zeitlin, Lydia H. Liu with Ellen Widmer, eds, (Harvard-Yenching Monograph Series, 58), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2003. It is reprinted with the kind permission of the author with minor stylistic changes, and is presented in three parts:

A pdf version of this article can be accessed here. For more downloadable PDF-format research papers by Professor Wang, click here.— The Editor

A site is often a topos in that it both marks a locus and serves as a topic. It is a common place that can be traversed or inhabited by a public and a rhetorical commonplace familiar to both its author and his audience.[1] Although there is no exact equivalent in Chinese to the Greek word topos that conveniently collapses the dual senses of locus and topic, the notion of ji 蹟 (site, trace, vestige) comes close. A ji is a site that emphasizes 'vestiges' and 'traces'. It is a peculiar spatial-temporal construct. Spatially, a landmark, such as a tower, a terrace, a pavilion, or simply a stele, serves as its territorial signpost or perceptual cue, and it is perceived to be a terrain distinct from the humdrum environment. Temporally, this plot of ground resonates with the plot of some vanished cause or deed. A landmark alone, however, does not make a site. No site in China is without an overlay of writing. To make a site is to cite texts. Listed in local gazetteers and literary anthologies, each site (ji) gathers under its heading a body of writing by a succession of authors of the past. It is therefore as much a literary topic, as it is a physical locus; it comes laden with a host of eulogies and contemplations.[2] A site is therefore textualized.[3] Once a locus congeals into a topic, its associated body of writing imbues it with a conceptual contour and an aura of distinction. A site is thereby perpetuated in the textual universe or by word of mouth, and consequently its topographic features and its landmarks become a secondary and tangential matter.[4] Cycles of decay and repair may render the landmark into something widely different from the original. That matters little. The only function of the landmark, after all, is to stand as a perceptual cue or synecdoche for the proverbial construct called a 'site', a somewhat deceptive notion premised on the primacy of physical place, topographic features, and prominence of landmarks. In reality, a site is a topos etched in collective memory by its capacity to inspire writings on it and the topical thinking it provokes. To visit a site is to take up that topos. In China, few literarily inclined visitors can resist that urge. All they need is a prompt from a stele or a pavilion, landmarks that purport or pretend to have links to the vanished past that the site once witnessed.

Fig.1 Huang Yanpei, Leifeng Pagoda at Sunset. Photograph. 1914. After Zhongguo mingshen (Scenic China), no. 4: West Lake, Hangchow [HangzhouJ, ed. Huang Yanpei et al., 2: 19 (Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1915).

A pagoda site is a curious anomaly.[Fig.1] With its soaring height, the pagoda is easily the most prominent kind of landmark that stakes out a site. Yet it is not an easy topos. Other architectural types are more favored for the topoi they facilitate. A terrace often marks the location of a bygone imperial palace and hence a reminder of an unfulfilled cause that occasions posterity's sighs and lamentations. A tomb is an easy topos for mourning a historical figure whose martyrdom can be appropriated as a mirror for self-pity. A pavilion with its command of an open view stretching to the horizon, inspiring an outpouring of transcendental sentiments, is a commonplace of literary exercises. Not so for a pagoda with its dark overtones of numinous otherness. As a Buddhist monument that commemorates the Buddha Sakyamuni's sacred traces, it was adapted in China as a ritual signpost that facilitates the deceased's journey into the afterlife. A pagoda borders on the numinous realm and evokes dark supernatural forces that it seeks to pacify. Traditional Chinese literati were ill-disposed in their outings to note such unsettling matters. Moreover, the dearth of established discursive precedents make the pagoda less of a topos. One exception is the displacement of a pagoda into a tower or a pavilion on a height; it then became co-opted into the topoi surrounding pavilions, a topic about transcendental immortality in the Daoist imaginary.

Precisely because of its otherness, a pagoda presents itself as a potential alternative topos, one that engages the supernatural, the numinous, and the demonic. In traditional China, it was taken up by writers who explored folkloric sources as a reaction against an archaicizing orthodox taste. In modern times, it has engaged radical authors who tap the demonic other as a source of creative and subversive energy. To follow the perceptions and discursive use of a pagoda serves therefore not so much a purely architectural-historical interest as a literary one—it allows us to understand the role of physical signposts in generating a discourse. No other pagoda serves this purpose better than the Leifeng Pagoda 雷峰塔.

Tope and Texts: The Apocalyptic Prelude

Fig.2 Anonymous, West Lake. Ink on paper. Handscroll. Southern Song (1127-1279) period. Shanghai Museum.

To the west of the city of Hangzhou lies one of it most famous attractions, West Lake. Stepping out of the city and walking toward the lake, one sees on the left a hilly promontory jutting into the lake. The promontory is called Leifeng, Thunder Peak,[5] an extension of the South Screen Mountain that lies to its south.[Fig.2] The pagoda, which stood on the hill until it collapsed in 1924, was popularly known as the Leifeng Pagoda. It was built by Qian Hongchu 錢弘俶 (929-88) and his consorts in A.D. 976. Qian was the last ruler of Wu-Yue 吳越, a state struggling for survival when most of China had been unified by the Song in the north. Qian paid homage to the Song court and made sure that none of his symbolic trappings and protocols displayed separatist ambitions.

From the very beginning, the pagoda was deeply involved with writing and texts. Its brick tiles were molded with engraved names or cryptic ideographs. A vast number of the hollow tiles had holes in which were inserted a Buddhist dharani-sutra,[6] prefaced with a votive inscription: 'Qian Chu, Generalissimo of the Army of the World, King of Wu-Yue, has made 84,000 copies of this sutra and interred them into the pagoda at the West Pass as an eternal offering. Noted on a day of the Eighth Month of the Yihai Year.'[7] The content of the sutra is strikingly congruent with the historical circumstances behind the construction of the pagoda and surprisingly prophetic of its fate. At the request of a brahman named Vimala Varaprabha, the sutra narrates, the Buddha leads his entourage to visit the brahman's home to receive his offering. On his way, he passes a park with an ancient stupa in decay. 'In decrepitude and shambles, the stupa was reduced to a mere earthen mount, overgrown with brambles and hazel grass, with debris strewn around.' The Buddha circumambulates the stupa ruin for three rounds and then takes off his robe to cover it. 'Tears begin to stream down his cheeks, mixed with blood. Having wept, he smiles. At that time, the Buddhas of Ten Directions, all weeping, fix their gaze on the stupa. Their radiance illuminates the stupa.' Asked why he weeps, the Buddha explains: the mount used to be a seven-treasure stupa. Normally a structure enshrining a Buddha's 'whole body' would have defied decay. But 'in posterity that is overcome by the End of the Dharma when the multitude practice heresies, the Wonderful Dharma ought to disappear.... It is this reason,' says the Buddha, 'that causes me to shed tears.'[8]

Fig.3 Sutra frontispiece from the Leifeng Pagoda. 16th century.

A surviving copy contains an illustration of the passage cited above[9] that shows the Buddha present at the ruined mound and causing it to emit radiance. Behind the Buddha is the treasure stupa in its original form.[Fig.3] The graphic demonstration of the decaying of what initially is a splendid structure is a rather sobering visual parable.

The decision to place an illustrated version of this sutra inside the Leifeng Pagoda was poignantly significant. Only three years after the construction of the pagoda, the prophecy of the 'end of the Dharma' was fulfilled: the Wu-Yue kingdom was terminated.[10] Some five hundred years later, the pagoda itself was reduced to a ruin.

From the very outset, the pagoda was a breeding ground for fiction. Tradition has it that the pagoda was built for Qian's consort, Lady Huang 黃妃, and texts often refer to it as Consort Huang's Pagoda (Huangfei Ta 黃妃塔). In truth, there never was a Lady Huang.

A dedicatory inscription, written by Qian Hongchu and recovered from the pagoda, relates that the pagoda was built for pious reasons by a Buddhist layman, namely Qian himself, who 'never stops reciting and poring over Buddhist sutras in the little spare time between ten thousand administrative affairs.' It identifies an 'Inner Court' donor (a consort) who possessed a 'lock of the Buddha's hair' and wished to have a pagoda built to enshrine it.

Initially, she planned to build a thirteen-story affair. Financial strains made this impossible, and a seven-story tower was the compromise. Six hundred strings of cash were spent on the project.[11]

The identity of the 'imperial consort' remains a mystery. According to a thirteenth-century copy of Qian's inscription, the pagoda was named after Huangfei (Consort Huang). The standard history, which tends to be meticulous, if not entirely accurate, in documenting kings' and princes' consorts and family members, records that Qian had two consorts in succession, one named Sun and the other named Yu; neither of them was named Huang. The 'Consort Huang' mentioned in the transcribed version of the inscription may well have resulted from a confusion between wangfei (royal consort) and huangfei 黃妃 (Consort Huang), which in southern pronunciation are nearly identical. In the process of transcribing or typesetting the inscription, wang may have been rendered as huang.[12]

It is not clear which consort was the force behind the pagoda construction. Qian's wife Sun Taizhen 孫太真 accompanied her husband on his trip north to pay tribute to the Song court. Song Emperor Taizu made a controversial decision to confer the title 'imperial consort of the Wu-Yue kingdom' on her, against opposition from his prime minister, who argued that a local prince's wife was not entitled to such an honor. Sun died in the first month of 977.[13] Qian's next wife was Lady Yu, who did not claim the title of 'imperial consort.' The near-coincidence between Sun's death and the date of the construction of the pagoda points to a connection with her, either during her sickness or her funeral, a standard practice in medieval China. In any event, a possible corrupt textual transmission may have spawned the fiction. Taking cues from the inscription, Wu Renchen 吳任臣, the Qing dynasty author of the Spring and Autumn of the Ten Kingdoms (Shiquo chunqiu 十國春秋), created a biography of this Consort Huang out of the profiles of Qian's two real consorts.[14] This he did in the spirit of writing history. In retrospect, the veiled association of the pagoda with a mystery woman is significant since women do figure prominently in the later popular tales that accumulated around the pagoda.[15]

Pagoda and Pavilion

In the first two centuries after its construction, the Leifeng Pagoda did not become much of a site. Following the Wu-Yue Kingdom, the Song ruled the Hangzhou area. The Thunder Peak Pagoda underwent a succession of notable renovations in the twelfth century.[16] Although its presence on the hilltop is unquestionable, there is no indication until the mid-thirteenth century that visitors to the site paid much attention to it. Su Shi 蘇軾 (1036-1101), who twice held an official post in Hangzhou, wrote profusely and enthusiastically about various scenes around the lake. As the temple gazetteer indicates, he visited the ]ingci Monastery 淨慈寺, whose grounds included the Thunder Peak Pagoda, and bequeathed poems to the abbey. His poems fancifully conjure up the oneiric image of the 'golden crucian carp' of the South Screen Mountain on which the Thunder Peak Pagoda stood (JCSZ, pp.4020-21), but not the pagoda itself. In fact, nowhere in the huge number of works by Su Shi inspired by West Lake is the pagoda mentioned. Either the sight of the pagoda simply did not register with him, or it did not strike him as worthy of mention.[17]

Lu You 陸游 (1125-1210) was another of the notable literary figures who visited South Screen Mountain. In his 'Note on the South Garden,' he mentioned that he did 'look left and right' (JCSZ, pp.4057-58). Still, the Thunder Peak Pagoda was simply not on his horizon. Likewise, Qisong 契嵩 (?-1071), an eminent monk of the Lingyin Monastery 靈隱寺 in the lake area, left a detailed description of an ascent of South Screen Mountain. Upon reaching the mountain top, with its sweeping view of the four quarters, he was overcome with lofty sentiments, but he spent not a drop of ink on the Thunder Peak Pagoda. Not that he was insensitive to landmarks. In fact, he took care to mark and punctuate his itinerary with pavilions. He began his trek with the Cloud-Clearing Pavilion and then passed by the Green-Gathering Pavilion, the Seclusion-Commencing Pavilion, and the White-Cloud Pavilion. He made a point of recording his trip 'so that the future generation may admire [him] as a traveller.'[18] In so doing, he also left a puzzle. One would imagine that unobtrusive pavilions are likely to be lost in the lush mountain forest. They simply do not compare in prominence with a pagoda on a hilltop. Why did Qisong pay meticulous attention to pavilions at the expense of the Thunder Peak Pagoda, which was no doubt in his visual field? His preference speaks volumes about the kind of values attached to these different architectural sites.

To a traditional Chinese writer, not all architectural sites make a topic. The monumental grandeur of the structure itself has almost nothing to do with this. Typically, the kinds of landmarks that serve as topics for a writer are towers, terraces, kiosks, and pavilions (lou 樓, tai 臺, ting 亭, ge 閣)—some for their nostalgic associations with imperial palaces or the vanished glories of remote or bygone eras; others for their open views of distant landscapes, which prompt transcendent aspirations.[19] In other words, landmarks and monuments are deemed worthy of remarking only when they accommodate two major topoi: contemplation of the vanished past (huaigu 懷古) and journey to the lands of the immortals (youxian 遊仙), that is, immanent Confucian sentiment and transcendent Daoist yearning. The former may thus encompass a tomb of a martyr-minister or a chaste woman or the ruins of an imperial palace. Compared with these, Buddhist sites attract less profound discursive ruminations. The pagoda, the foremost example of Buddhist architecture, commands conspicuously less writing than a famous imperial consort's tomb. Whenever it does inspire writing, it is only because the pagoda is displaced in the mind of the writer and becomes a 'cloudscaling' tower (lou) good for immortal-aspiring thoughts. Even such an eminent monk as Qisong found little to say about the Thunder Peak Pagoda while leaving no stone unturned when it came to pavilions.[20]

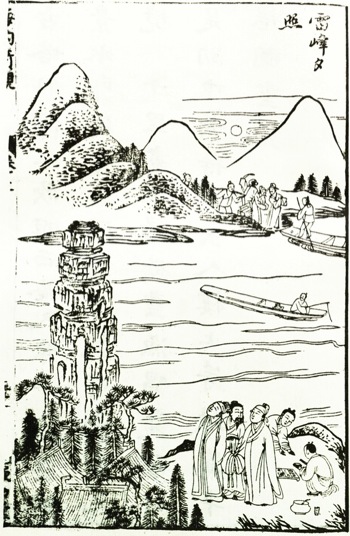

Fig.4 Map of Ten Views of West Lake

The situation of the Leifeng Pagoda improved somewhat in thirteenth century. Some local dilettantes (haoshizhe 好事者; literally, 'busybodies') divided the scenery of West Lake into ten topics known as 'Ten Views of West Lake',[21] [Fig.4] modeled after the popular imaginary topography of 'Eight Views' of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers.[22] The 'Fishing Village in Evening Glow' from the Eight Views of Xiao Xiang became 'Thunder Peak in Evening Glow' of West Lake. The Leifeng Ta became the centerpiece of this view and consequently the topic for eulogies.[Fig.5] The writings inspired by the pagoda were, however, rather generic, the kind engendered by any tower or pavilion.

Romancing the Pagoda: From 'Ancient Site' to 'Aberrant Site'

In the Jiajing era of the Ming dynasty (1522-66), there emerged a discursive interest in taking a pagoda on its own terms instead of treating it as a displaced tower. Some time before 1547, a well-known publisher named Hong Pian 洪楩 printed Stories by Sixty Authors (Liushi jia xiaoshuo 六十家小說),[23] a collection of tales drawn largely from the oral storytelling tradition. Included in the collection is 'The Story of the Three Pagodas'.

Set in West Lake, the story concerns Xi Xuanzan 奚宣贊, a young man of Lin' an [Hangzhou], who rescues a young girl named Bai Maonu 白卯奴 who has lost her way and reunites the young girl with her family. Xi meets the young girl's mother, a sensuous woman dressed in white, and the girl's grandmother, who is attired in black. Xi becomes the lover of the woman in white, who customarily kills her previous lover when she takes a new one. The same misfortune would have befallen Xi had it not been for the intervention of the young girl. Eventually a Daoist exorciser exposes the true identity of the three women: the young girl turns out to be a black chicken; the woman in white, a white snake; and the woman in black, an otter. The exorciser raises funds to build three stone pagodas in West Lake. The three monsters are subjugated beneath them. Xi becomes a religious layman.[24] The tale of the Three Pagodas is the oldest surviving story of the White Snake woman involving a pagoda.[25]

The story of a young man's romantic involvement with a snake-turned-woman has a long tradition in Chinese literature.[26] The Taiping guangji 太平廣記, for instance, devotes four entire juan to narratives of human encounters with snakes. One story tells of a young man named Li Huang 李黃 whose erotic encounter with a white snake-turned-beauty ends in his horrible death in a deserted private garden.[27] In the same juan of Taiping guangji, a group of visitors to Mount Song gather under a pagoda. They kill a snake several zhang 丈 long encircling the inner pillar of the pagoda and in due time are struck down by thunder.[28]

Fig.5 Ye Xiaoyan, 'Leifeng Pagoda at Sunset.' Ink and color on silk. Album leaf from the set Ten Views of West Lake. 13th century. National Palace Museum, Taibei.

For our purposes, what is remarkable about the story of the Three Pagodas is its interest in 'ancient sites'. It begins by noting the famous sites in the West Lake district: the Hall of Three Worthies, the Temple of Four Sages, the Vestige of Su Dongpo, and the Old Residence of Lin Bu, and so forth. It ends with the building of Three Pagodas to subjugate the three monsters. Moreover, it refers to the location of the Three Pagodas as 'an ancient site that has survived up to this day'.[29]

The author thus gives a bold new twist to the sense of an 'ancient site'. Technically, the Three Pagodas indeed qualified as 'ancient sites' in the sixteenth century. Back in the late-eleventh century, Su Shi, then prefect of Hangzhou, had built three pagodas on the lake, close to the islet near the south shore of West Lake, as territorial and boundary markers to control private farming activities on the lake. The site became one of the Ten Views of West Lake in the thirteenth century.[Fig.6] In the late fifteenth century, the greed and corruption of monks of the Buddhist monastery on the nearby islet enraged Yin Zishu 陰子淑, a government inspector known for his strict and bold administrative decisions. Yin ordered the monastery and pagodas 'instantly destroyed'. So when 'The Story of the Three Pagodas' was published, the Three Pagodas were either nonexistent or in ruins, since they were not rebuilt until 1611.[30] In either case, they were 'ancient sites' (guji 古蹟).

Fig.6 Ye Xiaoyan, 'Three Stupas Reflecting Moonlight.' Ink and color on silk. Album leaf from the set Ten Views of West Lake. 13th century. National Palace Museum, Taibei.

Curiously, although any 'traces' (ji) of Su Dongpo's activities are usually diligently catalogued and often invented,[31] the site of the Three Pagodas, which are unquestionably associated with him, was not accorded the prestigious designation ancient site. For one thing, in the sixteenth century the criteria for the 'ancient' or 'archaic' (gu) were quite strict. Nothing short of Han prose and High Tang poetry qualified as 'ancient'. A site associated with a Song figure, despite his fame, was consequently not 'ancient.'

The location, however, acquired the august appellation 'ancient site' in conjunction with a high tale of the demonic. This odd association reflects an inner tension of the period. The archaicizing taste that put a premium on the literary standards of the Han and High Tang still dominated the first half of the sixteenth century. At the same time, a new interest in the contemporary 'racy words from the streets', or folkloric ballads and tales, began to gather momentum. Open-minded scholars, such as Li Kaixian 李開先 (1502-68), were making a strong case for romance (chuanqi 傳奇) and other popular forms of folkloric literature.[32] Even Li Mengyang 李夢陽 (1473-1530), the most prominent proponent of archaism and a major force in shaping antiquarian taste, conceded late in his life that 'nowadays, authentic poetry comes in fact from folkloric sources'.[33] The association of the snake-woman story with a physical location labeled an 'ancient site' therefore either reconciles the two competing impulses or legitimizes the burgeoning interest in folkloric literature.

Nor is it entirely surprising that a tale of the demonic such as the White Snake should be sited in a pagoda. In the mid-sixteenth century when the tale of the White Snake was taking shape in printed and stage versions, several pagodas were likely candidates to become the setting of the tale. Quite a few sites of pagodas in the lake area were associated with snake lore. The pagoda on the Southern Peak, also built under Qian Hongchu in the tenth century, stood close to Bowl Pond (Boyu Tan 鉢盂潭), a name that prompts an association with the bowl used by the monk Fahai 法海 to contain the white snake, as described in a story in Feng Menglong's 馮夢龍 (1574-1645) collection (see below, and 'West Lake Liberated' in Features). Beside the pond is White Dragon Cave. A huge boulder nearby is allegedly the altar where a Daoist once pacified a monster.[34] The Baoshu Pagoda 保叔塔 on the Northern Mountain across the lake was also built in the tenth century. Toward the end of fifteenth century, a thunderbolt killed three itinerant monks inside the pagoda together with a 'huge snake which weighed fifty pounds. In its belly were ten or so white embryos': Soon after, the pagoda collapsed into ruins.[35]

At some point the ruins of the Three Pagodas and, across from them on the south shore, the Leifeng Pagoda became the setting of the story in printed versions. It appears that in the mid-sixteenth century, the story was not yet linked to a specific pagoda. In his topographic account of West Lake, Tian Rucheng 田汝成 (jinshi 1526) recorded a 'popular saying' that the White Snake and Green Fish, two monsters from the lake, were imprisoned beneath the Leifeng Pagoda.[36] Elsewhere, he told a story of a young man named Xu Jingchun 徐景春 who has an amorous encounter on the lake with a beautiful woman attended by a maid. After a night of dalliance, the woman gives the man a 'double-fish fan' as a souvenir. The man wakes up near the woman's grave.[37] The narrative resonates with the White Snake story in its cast and relationships, although it has no pagoda. Tian also noted, in a separate context, that the taozhen 陶真 performers of the lake area told stories set in the Southern Song (taozhen were a kind of chantefable, or 'singspeak', popular in the lower Yangzi region). Their repertoire included the tales of the Double-Fish Fan and the Leifeng Pagoda, which were treated as two separate stories. In the meantime, the White Snake lore was increasingly wedded to the Leifeng Pagoda. Surviving librettos of stage plays, with prefaces dated in the 1530s, include such titles as 'Madame White Clasped Under the Leifeng Pagoda for Eternity'.[38]

The Leifeng Pagoda had its share of snake lore, an association that may have prepared the way for its linkage with the White Snake story. During the late-Northern Song, the pagoda was damaged in warfare between the imperial army and peasant insurgents. The affiliated monastery was destroyed, leaving the pagoda alone 'standing dilapidated' amid brambles. Around 1130, a Southern Song construction force decided to pull down the pagoda to use its materials to fortify the city walls of Hangzhou against the northern Jurchen invaders. 'Suddenly,' according to a twelfth-century record, 'a huge python appeared, encircling the foundation [of the pagoda].... The numinous site (lingji 靈蹟) has thus manifested itself.' The curious happening stopped the demolition and led to the restoration of the pagoda later in the twelfth century.[39]

Fig.7 Leifeng Pagoda in ruins. 1920s. After Tokiwa Daijo. Shina bukkyo shiseki hyokai (Buddhist monuments in China) (Tokyo: Bukkyo shiseki kenkyukai, 1931). vol.5, pl.55.

An incident in the mid-sixteenth century may have strengthened the association between the Leifeng Pagoda and the White Snake. In 1553, pirates and bandits harassed the coastal region, including the lake district.[40] A rogue army of 3,000 troops turned the monastery into their barracks, sending monks in flight, 'scurrying like rats.' The soldiers ruined the landscape: 'All the bamboos were razed' (JCSZ, 4042a). During this period of military chaos, a fire broke out in the pagoda. It burned away all the wooded eaves and interior stairways and left the pagoda an 'empty shell,' a colossal ruin with rampant plants growing from its brick eaves.[41] [Fig.7] Before the fire, the exquisite architectural structure had evoked, by virtue of its association with a Buddhist monastery, a kind of Chan tranquility that fulfilled people's expectations of a landscape vista. The fire fundamentally changed the character of the pagoda and gave it a desolate mood. The ruin may have spawned fantasies about the demonic and may have made its association with the White Snake lore all the more compelling. In the Wanli years (1573-1620), the tale circulated that 'the Buddhist master contains the White Snake in a bowl and clasps it under the Leifeng Pagoda. Tradition has it that underneath the Leifeng Pagoda are two snakes, one green and one white.'[42]

Certainly by the early seventeenth century, the link between the White Snake and the Leifeng Pagoda was cemented. Yu Chunxi 虞淳熙 (?-162l) noted in the 1609 edition of the Qiantang County Gazetteer:

According to a popular saying, the Leifeng Pagoda serves to subjugate the monsters White Snake and Green Fish. People, old and young, keep telling the story to one another. During the Jiajing period, the pagoda belched smoke that spiraled up into the sky. They said it was the two monsters spouting venom. A closer look revealed that it was only swarms of insects. The romance (chuanqi) is indeed false.[43]

Yu also wrote a poem on the Leifeng Pagoda, which ends with the line 'The serpentine monster traverses the stone blocks.'[44]

The definitive touch comes from the short story 'Madame White Eternally Subjugated Under the Leifeng Pagoda', which is included in Feng Menglong's Jingshi tongyan 警世通言 (1624). This narrative version is not only the earliest surviving comprehensive account of the subject,[45] but it also solidified the Leifeng Pagodas position as the topographic locus for the story:

[Having turned Madame White and her maid into their original form of a snake and a fish], the venerable monk picked up the two tame creatures with his hand and dropped them into the begging bowl. He then tore off a length of his robe and sealed the top of the bowl with it. Carrying the bowl with him and depositing it on the ground before Thunder Peak Monastery, he ordered men to move bricks and stones so as to erect a pagoda to encase the bowl and keep it inviolate. Afterward Xu Xuan went about collecting subscriptions, and the pagoda eventually became a seven-tiered structure, so solid and enduring that, for thousands of years to come, the White Snake and Green Fish would be prevented from afflicting the world. When the venerable monk had subjugated these evil spirits and consigned them to the pagoda, he composed a chant of four lines:

When the West Lake is drained of its water

And rivers and ponds are dried up,

When Thunder Peak Pagoda crumbles,

The White Snake shall again roam the earth.[46]

All subsequent narrative versions and dramatic adaptations of the story end with this scene. The pagoda site thus truly becomes a topos, a common place (hence a commonplace) that admits a concentrated topical thinking and invention, a foundation or a scaffolding on which fiction and drama could be built.

This is indeed what happened later. One of the major theatrical adaptations after the seventeenth-century short story was Huang Tubi's 黃圖珌 1738 stage play The Leifeng Pagoda. In Huang's play, the construction of the Leifeng Pagoda becomes the structural framework: the play both begins and ends with it. In the opening scene, the Buddha anticipates the romance involving the White Snake and instructs Fahai to build a seven-story pagoda after the model the Buddha gives to him so that the 'two monsters' can be subjugated under it for eternity. The play ends exactly as the opening anticipated.[47]

Nearly contemporary to Huang's adaptation is a script allegedly by a famous actor named Chen Jiayan 陳嘉言 and his daughter, a version that is staged more often. It survives in later copies and is still performed today.[48] In 1771, based on this version, Fang Chengpei 方成培 readapted the tale for the theater. Not only did Fang retain the title The Leifeng Pagoda and continue to use the pagoda construction as the structural framing device, but the pagoda looms even larger in his theatrical universe. Before the snake woman is subjugated and imprisoned under the pagoda, she gives birth to a child who grows up to succeed in the official examination system.[49] No longer is the final pagoda scene purely an act of subjugation. In an emotionally wrenching scene, the son pays a visit to his entombed mother and seeks her release. The pagoda, in fact, has become a prison. Obeying the traditional imperative of happy ending, the Buddha releases the snake woman and arranges for her and her husband to ascend to the Tushita Heaven.

By this point, the Leifeng Pagoda had become more than a mere setting and framing device; it is now truly a topos that can generate further narrative and dramatic possibilities. To intensify the emotional resonance of the play at its close, the playwright directs the audience's attention not to the characters in the play but to the pagoda itself. One of the Buddha's attendants suggests that the pagoda be destroyed. No, says the Buddha, it ought to be left for the posterity to look up to. The play thus ends first with the invitation: 'Why not turn to West Lake and take a look at the soaring pagoda in evening glow?' This is followed by a poetic pastiche of eight lines, each taken from a Tang poet, celebrating the grandeur of the pagoda and the moral of the play. The pastiche thematizes the working of a topos: a pagoda is but a topic under which one can gather textual bits as building blocks to make a 'soaring pagoda.' To elaborate on the play is to build on the architectonic topos of the Leifeng Pagoda. It comes as no surprise that many subsequent playwrights seized on the pagoda scene to create dramatic situations. With the evocative pagoda as a locus and a cue, endless inventions and variations on the same theme become possible. In one Suzhou tanci 彈詞 (a storytelling performance to the accompaniment of string instruments), for instance, the snake woman gives birth to a child right inside the pagoda.[50] The pagoda is where the drama is.

The evocative power of the Leifeng Pagoda as a topos derives not so much from its architectural monumentality as from its efficacy as a haunted ruin that puts people in touch with the strange and the otherworldly. The generic associations of a ruin constitute a sufficient cue for writers to elaborate on the topos. The libretto of a popular storytelling performance (zidishu 子弟書) on the Leifeng Pagoda paints a chilling word picture:

The pagoda top soars into the sky. In the morning and evening views, it blocks out the sun and the moon. It metamorphoses into unpredictable moods with cloud and smoke, varying with the sun and rain. ...The bleak sight is certainly saddening. The melancholy cloud hovers closely around the pagoda top. Dark vapors surround its base. Mournful winds from the four quarters rattle the bronze bells; drizzles chill the green tiles of the thirteen stories. Strange birds on top of the pagoda crow dolefully as if decrying an injustice. ...And this is the sight of the Leifeng Pagoda at sunset. What a strange view![51]

Accuracy counts for little here; the Leifeng Pagoda has never been thirteen-story high, nor did it ever have green tiles. Either the writer had never seen the Leifeng Pagoda in person or he thought the empirical facts about the real Leifeng Pagoda irrelevant. For him and his audience, the Leifeng Pagoda was a topos, which one attaches words and situations. Whereas Huang Tubi, the author of the 1738 version of Leifeng Pagoda, was apologetic about the liberties he took with the Leifeng Pagoda and worried that they may have tarnished the reputation of the 'thousand-year-old famous site', Fang Chengpei, the playwright of the 1771 version, was unrepentant about his project of 'transforming the stinking decay into a miraculous wonder and alloying gold out of the debris of a ruin.' In a preface to the play, Fang noted: 'This pagoda, otherwise known as Huangfei Pagoda, was built by an imperial consort of the Wu-Yue kingdom. ...It was ruined by fire during the Jiajing period. Whether the matter of the Buddhist master of Song subjugating the White Snake is true or not is simply irrelevant.'[52] The pagoda is, as the closing lines of Huang's play would have it, 'the site for visitors in the next thousand years to come to admire and sigh; it is what is left for the Buddhist community to perpetuate tales.' Moreover, it is not just any ordinary topos, but one that allows posterity 'to talk about sprites and spirits unlike humans, [a site where] a familiar situation may be transformed into an extraordinary scenario.'[53] In other words, it is a topos for the supernatural and strange.

Fig.8 Chen Yiguan. 'Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow.' Carving by Wang Zhongxing of Xin'an. In Strange Views of the World ( Hainei qiguan). 1609. comp. Yang Erzeng. After Zhongguo gudai banhua congkan erbian (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1994). 8: 269.

The Story of the Three Pagodas, the earliest surviving printed version of the White Snake story, is reticent about the demonic nature of the pagoda site where the subjugation of the monsters takes place. It chooses to veil it with the phrase 'an ancient site and surviving trace' (guji yizong 古蹟遺蹤).[54] By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, such reticence was no longer necessary. The site of the Leifeng Pagoda was recognized as the 'aberrant site' (guaiji 怪蹟).[55] Mo Langzi 墨浪子, a southern writer of the Kangxi period (1662-1722), cast his stories in a purely topographic framework. Each of the sixteen stories published in his Wonderful Tales of West Lake: Sites Ancient and Modern (Xihu jiahua gujin yiji 西湖佳話古今遺跡) is attached to a specific 'site' (ji). Moreover, each is characterized as a particular kind of site: an 'immortal's site,' an 'administrative site,' a 'man of talent's site,' a 'poetic site,' a 'dream site,' a 'drunken site,' a 'laughing site,' a 'romantic site,' an 'imperial site,' a 'regretting site,' and so on. The Leifeng Pagoda is the 'aberrant site' (guaiji), and Mo made a point of defending the 'aberrant':

I used to bear in mind Confucius' dictum that one ought not to speak of the aberrant. Hence I considered it trifling to bother with devious actions and matters that border on absurdity and would leave them aside. But, given the immensity of the universe, is there anything that does not happen? Absurdities are indeed not worth accounting for, but what if a matter can be traced [to its origin] and its site still survives? Take, for example, the Leifeng Pagoda prominent on West Lake. Researching its origin, one finds that it was built to subjugate monsters. It has survived up to this day. The Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow has become one of the Ten Views of West Lake. The aberrant has been normalized. The tombs of royal martyrs and hills of immortals have received detailed narration and provided pleasurable viewing for thousands of years. Why should the matters that are at once aberrant and normal be a taboo? Why can't they lend themselves to a delightful hearing?

He ends his story with the advice: 'Those who admire the Leifeng [Pagoda] should visit the site and mull over the aberrant happenings (guaishi) associated with it.'[56]

Here Mo Langzi takes on the Confucian bias against 'the aberrant, the violent, the spiritual, and the strange.' The traditional moral taxonomy underlying canonical 'sites,' such as Confucian virtues of loyalty and the Daoist ideal of immortality, is found to be wanting. New categories of 'sites' are needed, such as the 'aberrant sites,' if only to revise our rigid classification system and expand our cognitive horizon, 'given the immensity of the universe.' Strategically, Mo Langzi tries to make his case by blurring the line between the aberrant and the normal. The force of his argument for the 'aberrant sites' lies in its subversion of traditional value systems. It is not that the aberrant sites have virtues in themselves; rather, there is something fundamentally wrong with their banishment from the cultural and moral topography. Mo Langzi's sixteen kinds of sites are a new cognitive mapping that reconstitutes cultural topography; the 'aberrant site' is one of the new features.

Fig.9 Mo Fan (16th c.), 'Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow.' In Strange Views of the World, 1609, comp. Yang Erzeng.

After Zhongguo gudai banhua congkan erbian (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1994), 8: 269.

The recognition of the aberrant sites had been anticipated at the beginning of the seventeenth century. In 1609, Yang Erzeng 楊爾曾, also known as the Dream-Traveling Daoist of Qiantang (Qiantang woyou daoren 錢塘卧遊道人), compiled and published the Strange Views Within the [Four] Seas (Hainei qiguan 海內奇觀). According to Yang, he was motivated by a desire to educate the armchair traveler: 'There are metamorphoses of clouds, fogs, winds, and thunders under the blue sky and the bright sun; there are strange and weird people, creatures, and plants in the sandy region of the Ganges River. The mountains and rivers yonder are truly quaint and unpredictable. ... [I] have therefore marked them out to show what one's eyes and ears cannot reach.'[57] The book includes a woodblock print of the 'Leifeng Pagoda at Sunset,' presumably as a specimen of 'the truly quaint and unpredictable.' Two young scholars, accompanied by an old rustic, stand at the foot of the pagoda and look up, apparently riveted by the spectacle of this ruined pagoda. Behind the scholars, two attendant boys are busy laying out inkstones and other instruments so that their masters can write down their thoughts on the spot.[Fig.8] The print visually makes a case for the pagoda as a topos: visit to the site occasions writing about it. Yang Erzeng matches the print with a poem on the same subject by Mo Fan, 莫璠, a mid-Ming writer [Fig.9]:

The setting sun bathes the ancient pagoda in ever-dimming red.

The shadows of mulberries and elms half-shroud the houses along the western shore.

The reflection of the evening glow lingers on the waves like washed brocade.

This Buddhist kingdom amid a cloud of flowers is no mundane realm.

Ten miles of pleasure boats nearly all beached on the shore,

The lake reverberates with the chants of fishermen and water chestnut gatherers, a landscape apart.

In a lakeshore pavilion, a person waits for the moon to rise.

Red curtains rolled up, the railings await the return of the visitor.[58]

There is a glaring disjuncture between the print and the poem attached to it. The poem, written before the fire reduced the pagoda to a ruin, rhapsodizes about the celestial splendor of the edifice and the idyllic landscape surrounding it; the print, made half a century after the fire, frankly presents the bizarre, fire-damaged pagoda as a curious sight. The print is more consistent with Yang's professed interest in the strange as articulated in his preface rather than the mellow poem anachronistically yoked to it. The disjuncture may have resulted from the compiler's intent to legitimize the newfound interest in the strange by a touch of elegance. It makes the indulgence in the strange sight as displayed in the print all the more an illicit pleasure.

Next

Notes to Part I:

The following abbreviations are used in the text and the Notes:

JCSZ

Jingcisi zhi (Gazetteer of the Jingci Monastery), comp. Ji Xiang (1805), in WZC, vol.13.

LXQJ

Lu Xun quanji (Complete works of Lu Xun), sixteen vols., Beijing: Renmin Wenxue Chubanshe, 1981.

NJSZ

Dahuo, Nanping lingcisi zhi (Gazetteer of the Jingci Monastery of Nanping) (1616), in Xuxiu siku quanshu, vol.719, Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, 1995-99.

WZC Wulin zhanggu congbian (Compendium of local histories of Wulin), comp. Ding Bing (1888), twelve vols., Taipei: Tailian Guofeng Chubanshe, 1967.

YWSQ

Yingyin Wenyuange siku quanshu, 1,500 vols., Taipei: Taiwan Shangwu Yinshuguan, 1983-86.

The formatting of the Notes follows the original text and does not conform to China Heritage Quarterly style.—Ed.

[1] David Leatherbarrow, The Roots of Architectural Invention: Site, Enclosure, Materials (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp.3-6.

[2] See Stephen Owen, Remembrances: The Experience of the Past in Classical Chinese Literature (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1986), p.26.

[3] Richard E. Strassberg. 'Introduction,' in Inscribed Landscapes: Travel Writing from Imperial China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), pp.6-7.

[4] Stephen Owen (pers. comm.) first made this point to me. See also his commentary on the body of writing in connection with the Level Mountain Hall in Yangzhou, in his An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginning to 1911 (New York: Norton, 1996), p. 634. Addressing the issue of visibility and the creation of place, Yi-Fu Tuan (Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience [Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977], p.178) also observes that 'deeply-loved places are not necessarily visible. ... Identity of place is achieved by dramatizing the aspirations, needs, and functional rhythms of personal and group life.'

[5] This commonly adopted translation may not be entirely adequate, for it ignores the origin of the character lei. Lei may have been a reference to a Daoist hermit named Xu Lizhi 徐立之, otherwise known as Mr. Huifeng 回峰, who once lived on the site. The name 'Huifeng' may have changed into Leifeng over time. Another theory has it that a man named Leijiu 雷就 once lived on the site. Hence, the hill was named after him as Thunder Peak. See Qian Yueyou 潛説友, Xianchun Lin'an zhi 咸淳臨安志 (Xianchun [period] gazetteer of Lin'an), YWSQ, vol. 490, pp.873-74; Tian Rucheng 田汝成, Xihu youlan zhi 西湖遊覽志 (Notes on touring West Lake) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1998), p. 33; and Chen Xingzhen 陳杏珍, 'Leifengta de mingcheng ji qita' 雷峰塔的名稱及其他 (The name of the Thunder Peak Pagoda and other issues), Wenwu tiandi, no. 6 (1977): 40-44.

[6] The complete tide is Yiqie Rulai xin bimi quanshen sheli baoqieyin tuoluoni jing 一切如來心秘密 (Sanskrit: Sarvatathagata-adhistanahrdaya-guhya-dhatu-karandamudra-dharani-sutra). It was first translated into Chinese by the Indian monk Amoghavajra (705-74), who went to China around 720, where he became a disciple of Vajrabodhi. The sutra can also be found in Bunyiu Nanjio, A Catalogue of the Chinese Translation of the Buddhist Tripitaka (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1883), no. 957. See also Soren Edgren, 'The Printed Dharani-sutra of A.D.956,' Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities (Östasiatiska Museet), no. 44 (1972): 141; and Zhang Xiumin 張秀民, 'Wudai Wu-Yue guo de yinshua' 五代吳越國的印刷 (The printing technology of the Wu-Yue kingdom of the Five Dynasties), Wenwu 1978, no. 12: 74-76.

[7] See Yu Pingbo 俞平伯, 'Ji Xihu Leifenta faxian de tazhuan yu cangjing' 記西湖雷峰塔發現的塔磚與藏經 (Note on the tiles and hoarded sutras inside the Leifeng Pagoda), in Yu Pingbo sanwen zawen lunbian 俞平伯散文雜文論編 (Prose and miscellaneous notes by Yu Pingbo) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1990), 123; Zhang Xiumin, 'Wudai Wu-Yue guo de yinshua,' p. 74.

[8] Edgren, 'The Printed Dharani-sutra of A.D. 956: pl.3.

[9] See ibid., p. 141. For other copies, see Zhang Xiumin, 'Wudai Wu-Yue guo de yinshua,' p. 76.

[10] Yu Pingbo ('Ji Xihu Leifengta faxian de tazhuan yu cangjing.' p. 126) first noted the poignant circumstantial referentiality of the sutra in the pagoda with regard to the fate of the pagoda itself.

[11] The inscription is contained in Qian Yueyou, Xianchun Lin'an zhi, p. 874. The pagoda was most likely built in 976, based on the dated sutras and woodblock prints excavated from the pagoda. The Baoqieying jing retrieved from the pagoda is dated 975, which points to the date of the beginning of the construction. The woodblock print bearing a pagoda image retrieved from the hollow bricks is dated 976. Since Qian Hongchu's votive inscription records that the pagoda was built 'within a moment of finger snap,' and considering that the Wu-Yue Kingdom ended in 978, it is very likely that the construction was completed in 976 or shortly after, but not beyond 978. See Chen Xingzhen, 'Leifengta,' p.42.

[12] Chen Xingzhen ('Leifengta: p. 42) argues convincingly that the huang (yellow) is a misprint in the Xianchun Lin'an zhi; it should be huang 皇 (imperial) or wang 王. Similar observations were also made by Qing scholars; see Hu Jing 胡敬, comp., Chunyou Lin'anzhi jiyi 淳祐臨安志輯逸 (Chunyou gazetteer of Lin'an, with scattered fragments reconstiruted), WZC, vol.24.

[13] Tuotuo 脫脫 (Toghto), Songshi 宋世 (Standard history of Song) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1977), 480.13900-901, 13909. Wu Yue heishi buyi 吳越備史補遺 gives the eleventh month of 976 as the date of her death; see Chen Xingzhen, 'Leifengta,' p.43.

[14] Wu Renchen 吳任臣, Shiguo chunqiu 十國春秋 (Spring and autumn of the Ten Kingdoms), YWSQ, 466: 112.

[15] The Jingci sizhi (4034a) records a popular saying that circulated widely in the region: tidal lappings on the Qiantang shore 'produce imperial consorts.' In particular, it mentions Qian Hongchu's consort, Sun Taizhen.

[16] A fire during the war in the Xuanhe era (1119-25) razed everything around the pagoda to the ground, leaving the latter standing alone. The pagoda apparently sustained some damage. It was renovated in 1171 and 1199; see Qian Yueyou, Xianchun Lin'an zhi, p.804.

[17] Su Shi himself was not uptight about discussing outlandish matters. He is closely associated with the telling of ghost stories as a literati pastime. He also authored a zhiguai 志怪 collection titled Dongpo zhilin 東坡志林 (I thank Judith Zeitlin for alerting me to this fact). However, his response to the Leifengta site is still conditioned by the stock generic impulse; in any case, the pagoda site did not inspire him to poetry.

[18] Qisong, 'You Nanpingshan ji' 游南屏山記 (Touring South Screen Mountain), in Xihu youji xuan 西湖遊記選, ed. and annot. Cao Wenqu 曹文趣 et al. (Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi chubanshe, 1985), pp.224-25.

[19] For an excellent study of the literary association of these architectural types, see Ke Qingming [Ko Ching-Ming] 柯慶明, 'Cong ting tai lou ge shuoqi: lun yizhong linglei de youguan meixue yu shengming xingcha' 從亭台樓閣說起:論一種另類的遊觀美學與省命省察 (Of kiosks, terraces, towers, and pavilions: notes on the aesthetics of excursions into otherness and existential introspection), in idem, Zhongguo wenxue de meigan 中國文學的美感 (Aesthetic modes of Chinese literature) (Taibei: Rye Fidd Publications, 2000), pp.275-349.

[20] The first source is Zhu Mu 祝穆 writing in 1240, according to whom the Ten Views are: (I) 'Autumn Moon Above the Placid Lake,' (2) 'Spring Dawn at Su Dike,' (3) 'Remnant Snow on Broken Bridge: (4) 'Thunder Peak Pagoda at Sunset,' (5) 'Evening Bell from Nanping Mountain,' (6) 'Lotus Breeze at Qu Winery,' (7) 'Watching Fish at Flower Cove: (8) 'Listening to the Orioles by the Willow Ripples,' (9) 'Three Stupas and the Reflecting Moon,' (10) 'Twin Peaks Piercing the Clouds' (see Zhu Mu, Fangyu shenglan 方禺勝覽 [preface dated 1240], cited in Xihu bicong 西湖筆叢 [Compendium of writings on West Lake), ed. Lu Jiansan 陸鑒三 [Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin chubanshe, 1981), p. 26). Half a century later, the same Ten Views were cited in Wu Zimu's 吳自牧 Mengliang lu 夢梁錄 although in a different order. The author artributes this tenfold landscape taxonomy to 'recent painters who claim that the most remarkable of the four seasonal scenes come down to ten' (see Wu Zimu, Mengliang lu [Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin chubanshe, 1980), pp.103-6). For a good introduction to the subject, see Huishu Lee,

'The Domain of Empress Yang (1162-1233): Art, Gender, and Politics at the Southern

Song Court' (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1994), pp.47-48.

[21] See Zhai Hao 翟灝 et al., Hushan bianlan 湖山便覽 (Easy guide to the lake and mountains) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji, 1998), p. 27; Wu Zimu, Mengliang lu, pp.103-6.

[22] For studies of the pictorial representation of Xiaoxiang views, see A. Murck, 'Eight Views of the Hsiao Hsiang by Wang Hung,' in Images of the Mind: Selections from the Edward L. Elliot Family and John B. Eliot Collection of Chinese Calligraphy and Painting, ed. Wen Fong et al. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), p. 214; Richard Barnhart, 'Shining Rivers: Eight Views of the Hsiao Hsiang in Sung Painting,' in Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Chinese Art History (Taibei: National Palace Museum, 1992), I: 45-95; and Valerie M. Ortiz, 'The Poetic Structure of a Twelfth-Cencury Chinese Pictorial Dream Journey,' Art Bulletin 76, no. 2 (1994): 257-78.

[23] For the book, see Patrick Hanan, 'The Early Chinese Short Story: A Critical Theory in Outline,' 179n21.

[24] Hong Pian 洪楩, ed., Qingpingshantang huaben 清屏山堂話本 (Nanjing: Jiangsu

guji chubanshe, 1989), pp.25-36.

[25] Most scholars agree that the story could date to the Southern Song. Many traits of the story (e.g., the place-names and official titles mentioned, the style of the prose) point to an early date. The story was in circulation at least by the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368). A catalogue of the Yuan zaju 雜劇 lists a play by the same title, now lost. See ibid., p.25; and Huang Shang 黃裳, Xixiangji yu Baishezhuan 西廂記與白蛇傳 (Romance of the West Chamber and Story of the White Snake) (Shanghai: Pingming chubanshe, 1954), pp.36-39.

[26] The subject has spawned a huge scholarly literature. See, e.g., Nai-tung Ting, 'The Holy and the Snake Woman: A Study of a Lamia Story in Asian and European Literature: Fabula 8 (1966): 145-91; Wu Pei-yi, 'The White Snake: The Evolution of a Myth in China' (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1969); Yen Yuan-shu, 'Biography of the White Serpent: A Keatsian Interpretation,' Tamkang Review I, no.2 (1970): 227-43; Hsu Erh-hung, 'The Evolution of the Legend of the White Serpent,' 2 pts., Tamkang Review 4, no. I (1973): 109-27, no. 2: 121-56; and Whalen Lai, 'From Folklore to Literate Theater: Unpacking Madame White Snake,' Asian Folklore Studies, 51 (1992): 51- 66.

[27] Li Fang 李昉 et al., comps., Taipingguangji 太平廣記 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1986), 10: 3752. Juan 456-59 (pp.3720-62) are devoted to snakes.

[28] Ibid., p. 3745.

[29] Hong Pian, Qingpingshantang huaben, pp.25-36.

[30] Tian Rucheng, Xihu youlan zhi, 2.20; Zhai Hao et al., Hushan bianlan, p. 70.

[31] Zhong Jingwen 鐘敬文, Zhong Jingwen minjian wenxue lunji 鐘敬文民間文學論集 (Essays on folkloric literature by Zhong Jingwen) (Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe, 1985), 2: 85.

[32] Li Kaixian 李開先, Li Kaixian ji 李開先集 (Complete works of Li Kaixian) (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1959), p.6.

[33] Li Kongtong quanji 李空同, juan 50: cited in Guo Shaoyu 郭紹虞 et al., eds., Zhongguo lidai wenlun xuan 中國歷代文論選 (Selected Chinese literary criticism of successive dynasties) (Shanghai: Guji chubanshe, 1980), 3: 55.

[34] Tian Rucheng, Xihu youlanzhi, 3.38: Zhang Dai 張岱, Xihu mengxun 西湖夢尋 (A dream search for West Lake), in Tao'an mengyi Xihu mengxun 陶庵夢憶西湖夢尋 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1982), 4.67.

[35] Tian Rucheng, Xihu youlan zhi, 8.86.

[36] Ibid., 3.33.

[37] Ibid., 26.481.

[38] The earliest surviving libretto is titled Yuhuatang zizhuan Leifengta chuanqi

玉花堂自傳雷峰塔傳奇 (Romance of the Leifeng Pagoda composed by Yuhuatang [Jade Flower Hall]), with a preface dated 1530, in the collection of Dai Bufan 戴不凡. Another libretto known as Nanxi yiyangqiang Jiajing shinian Jiguzhai keben Leifengta 南戲弋陽腔嘉靖十年級古齋刻本雷峰塔 (The Leifeng Pagoda in the Yiyang variety of Southern Drama from the Jigu Atelier, a woodblock print dated the tenth year of Jiajing), with a preface dated 1531, is in the collection of Wu Jingtang 吳敬塘. Since these two librettos have not been published, their content remains unknown. The connection made between the two monsters-turned-beauties and the pagoda is confirmed by another libretto, in print in 1532, titled Bainiangzi yongzhen Leifengta chuanqi 白娘子永鎮雷峰塔傳奇 (Madame White clasped under the Leifeng Pagoda for eternity, a romance). See Zhao Jingshen 趙景深 et al., 'The Relationship Between the Romance of the White Snake and Folklore' (in Chinese), in Baishezhuan lunwenji 白蛇傳論文集 . (Papers on the tale of White Snake), ed. Zhongguo minjian wenyi yanjiuhui, Zhejiang fenhui 中國民間文藝研究會浙江分會 (Hangzhou: Zhejiang guji chubanshe, 1986), p. 121.

[39] Yang Kang 楊亢, 'Record of Renovation' (dated 1199), in Hu Jing, Chunyou

Lin'an zhi jiyi, 24: 7358.

[40] Traditional sources identify the bandits as Japanese. Recent study shows that the mid-sixteenth-century coastal piracy involved ethnic Chinese just as well. See Richard von Glahn, Fountain of Fortune: Money and Monetary Policy in China, 1000-1700 (Berkeley: Universiry of California Press, 1996).

[41] Lu Ciyun 陸次雲, Huru zaji 虎濡雜記, in WZC, 4:2087. Qing authors attributed the fire to the Japanese invaders who suspected an ambush inside the pagoda; see ibid.: and Liang Zhangju 梁章鉅, Langji xutan 浪蹟續談 (More travelogues), vol.4 of Biji xiaoshuo daguan xubian 筆記小說大觀續編 (Collection of biji fiction: a sequel) (Taibei: Xinxing shuju, 1979), p. 4234.

[42] Tian Rucheng, Xihu youlan zhi, 3-33. Wu Congxian 吳從先, Xiaochuang riji 小窗日記, cited by Xu Fengji, Qingbo xiaozhi (Shanghai: Shanghai guji, 1999), p.77.

[43] Yu Chunxi 虞淳熙, Qiantang xianzhi 錢塘縣志 (Gazetteer of the Qiantang county), reprint of 1893, 'waiji: p. 33.

[44] NJSZ, p. 407. The poem was written before 1616, since it was collected in Dahuo's 大壑 Nanping Jingcisi zhi 南屏淨慈寺志, published in 1616.

[45] Feng Menglong 馮夢龍, comp., Jingshi tongyan警世通言 (Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1984), pp.435-64.

[46] Ibid., p. 464: trans. from H. C. Chang, Chinese Literature: Popular Fiction and

Drama (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1973), p. 260.

[47] Huang Tubi 黃圖珌, Leifengta 雷峰塔, in Baishezhuan ji 白蛇傳集. (A collection of White Snake stories), ed. Fu Xihua 傅惜華 (Shanghai: Shanghai chuban gongsi, 1955), pp.282-338.

[48] Fu Xihua, 'Preface,' in idem, ed., Baishtzhuan ji, p.5: Huang Shang, Xixiangji yu Baishezhuan, p.43.

[49] The invention of this plot is credited to actor Chen Jiayan and his daughter who adapted the White Snake materials for the stage, since Huang Tubi's version was considered not quite fitting for stage performance. Fang inherited Chen's plot. See A Ying 阿英, Leiftngta chuanqi xulu 雷峰塔傳奇敘錄 (Introduction to the Romance of the Leifeng Pagoda) (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1960), p.2.

[50] Baishe zhuan lunwen ji, p. 161.

[51] 'Mourning in Front of the Pagoda,' a print from the Guangxu era (1875-1908), in Fu Xihua, ed., Baishtzhuan ji, pp.110-11.

[52] Fang Chengpei 方成培, 'Preface to The Leifeng Pagoda,' in Zhongguo gudian xiqu xuba huibian 中國古典戲曲序跋彙編 (Collection of prologues and postscripts to traditional Chinese drama), ed. Cai Yi 蔡毅 (Ji'nan: Qilu shushe, 1989), 3:

1941.

[53] Huang Tubi, Leifengta, p. 338.

[54] Hong Pian, Qingpingshantang, p. 36.

[55] Huang Tubi (Leifengta, p. 335), for example, explicitly refers to the Leifeng Pagoda as a 'an aberrant site (guaiji) that bears viewing.'

[56] Mo Langzi, 墨浪子 Xihu jiahua 西湖佳話, ed. and annot. Shao Dacheng 卲大成 (Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi chubanshe, 1985), pp.266, 284.

[57] Yang Erzeng 楊爾曾, Hainei qiguan 海內奇觀 in Zhongguo gudai banhua congkan erbian 中國古代版畫叢刊二編. (Compendium of traditional Chinese prints, 2d series) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1994), p.26.

[58] The compiler of the Hainei qiguan did not disclose the source of this poem. I have been able to identify Mo Fan, a mid-Ming poet, as the author of this poem: see Zhejiang tongzhi 浙江通志 (Zhejiang gazetteer) (Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1934), 4: 4867a.

|