|

FEATURES

Tope and topos | China Heritage Quarterly

Tope and topos

The Leifeng Pagoda and the Discourse of the Demonic

Eugene Y. Wang 汪悅進

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Professor of Asian Art

Harvard University

Eugene Wang's important study of Leifeng Pagoda on West Lake expands our consideration of the Ten Scenes of West Lake—and what the Republican-era writer Lu Xun decried as the 'ten scenes syndrome' in China, as well as adding nuance to the history of the White Snake and the symbolism surrounding that now-perennial story.

This essay originally appeared in Writing and Materiality in China: Essays in Honor of Patrick Hanan, Judith T. Zeitlin, Lydia H. Liu with Ellen Widmer, eds, (Harvard-Yenching Monograph Series, 58), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2003. It is reprinted with the kind permission of the author with minor stylistic changes, and is presented in three parts:

A pdf version of this article can be accessed here. For more downloadable PDF-format research papers by Professor Wang, click here.— The Editor

An Alternative Topos: The Supernatural Naturalized

The strained yoking in Strange Views of the woodblock print of a strange sight with a poem praising serenity betrays an anxiety about the legitimacy of the strange.[59] The same kind of inner tension is also discernible in Huang Tubi's play. Once 'a gigantic pagoda' is set on the stage, as we read from the script, the monk Fahai exclaims: 'What a treasure pagoda!' He then sings:

[I shall] embrace the white cloud and green hill and fill them in the void of the pagoda.

The spirits' craftsmanship and demons' axes make it a model of extraordinary shape.

They are indeed a splendor of gold and blue hues.

From now on, among the Six Bridges and Ten Ponds,

The Leifeng Pagoda ranks as the top one.

It occasions poems with staying resonances.

It spawns paintings of a vast serenity and cool mood.[60]

The otherwise demonic White Snake and Green Fish are poeticized into innocuous 'white cloud and green hill.' The unruly supernatural intimation of ghosts and spirits is displaced into a supernatural force harnessed for construction of the pagoda, a trope often deployed in praising an architectural splendor. Moreover, the poems and pictures generated from this architectural topos are just one of those landscape pieces.

The Leifeng Pagoda indeed constitutes a topos of the strange, yet its strangeness ranges from the eerily supernatural and darkly demonic to the blithely transcendent. At one end of the spectrum is the bleak vision of the pagoda shrouded in 'dark vapors' and 'melancholy clouds,' with strange birds perched on its chilling 'green tiles' 'crowing dolefully' in the 'mournful wind.'[61] At the other end is the pastoral serenity of 'white cloud and green hill,' endowed with a touch of otherworldliness. Working with the same topos of the strange localized in the Leifeng Pagoda, dramatists and novelists, closer to folkloric culture, are more likely to toy with the dark force of the unruly monsters and spirits; the elite, on the other hand, tend to naruralize the supernatural, harmonize the disruptive, and use this topos, an intimation of the otherworldliness, to express eremitic aspirations.

Li Liufang 李流芳 (1575-1629), a literati-painter who frequented West Lake, is most responsible for propagating a transcendent topos out of the colossal ruin of the Leifeng Pagoda. In a colophon on his Leifeng Pagoda in Twilight, Li wrote:

My friend [Wen] Zijiang once said: 'Of the two pagodas on the lake, the Leifeng Pagoda is like an old monk; the Baoshu Pagoda [across the lake] a female beauty.' I really like this line. In 1611, while viewing lotus flowers in the pond with Fang Hui, I composed a poem: 'The Leifeng Pagoda leans against the sky like a drunken old man.' [Yan] Yinchi saw it and jumped to his feet, exclaiming that Zijiang's 'old monk' is not as good as my 'drunken old man' in capturing the mood and mannerism of the pagoda. I used to live in a pavilion on a hill overlooking the lake. Morning and evening, I faced the Leifeng [Pagoda]. There he is—a sagging old man hunched amid the mountains shrouded in twilight and violet vapor. The sight intoxicated me. I closed my poem with the line: 'This old man is as poised and aloof like clouds and water.' I did base myself on Zijiang's 'old man' trope. Written after getting drunk in the Tenth Moon of 1613.[62]

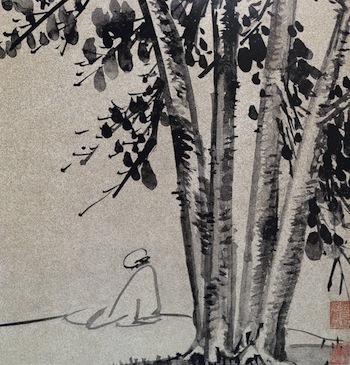

Fig.10 Li Liufang (1575-1629), "Monk Under a Tree." Ink on paper. Album leaf from Landscapes and Flowers. Shanghai Museum. After Zhongguo meishu quanji huihuabian Mingdai huihua, ed. Yang Han et al. (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin meishu chubanshe, 1988), 8:99, pl.92.4.

Much of this mood is captured in his painting of an old monk.[Fig.10]

Li Liufang earned his juren degree in 1606. The failure of his subsequent attempts at the advanced degree crushed any hopes he may have had of an official career. Frustrated, he settled for earning a living by tutoring and selling his writings. He took to drink to escape from financial embarrassments, severe illness, and the bleak late-Ming political landscape.[63] The images of the monk and a drunken old man he and his friend projected onto the Leifeng Pagoda are very much self-portraits: a convention-defying tipsy monk who rises above the world and plays his own games. Li curbed the mutinous energy of the image by qualifying the otherwise crazy monk with a mellowing old age and a 'sensibility as placid as the mist and water,' that is, anything but melodramatic, too old and exhausted to be swashbuckling despite inebriation. The Leifeng Pagoda plays right into Li's emotional needs.

Decrepit and strange, it nevertheless stands still.

The characterization of the pagoda as a drooping old drunkard or a monk proved to be an infectious topos that attracted a massive following. Even a fiercely imaginative writer such as Zhang Dai 張岱 (1597-1679) seems never to have got enough of this topos [see translations from Zhang Dai in Features—Ed.]. Four poems in his Tracing West Lake in a Dream are devoted to it:

Master Wen portrays the Leifeng Pagoda—

An old monk with his robe hanging there.

He watches West Lake day and night,

and never has enough of it in all his life.

Fragrant breezes come, every now and then,

West Lake is a couch for drunkards.

There he is, standing upside down, the old drunken man

In one breath, he gulps down the entire lake and all.[64]

The bleak and desolate Leifeng [Pagoda]

How can it stand the sunset at all?

Its body is all smoke and vapor,

Like an old man who lifts his long beards and howls.[65]

Elsewhere, he wrote about the 'Leifeng Pagoda at Sunset' as one of the 'Ten Views':

The crumbling pagoda borders on the lake shore,

A sagging drunken old fool.

Extraordinary sentiment resides in the rubble,

Why should the humans meddle with it at all?[66]

The trope of the Leifeng Pagoda as a drunken old monk is richly suggestive and apt for disgruntled literati. Its 'strange' and freakish overtones serve as a canvas for the projections of their disenchantment with worldly affairs and their aloofness and withdrawal from them; at the same time, the image is mellow enough to keep them free of any suspicion of strident excess and dark and demonic riotousness, examples of bad taste and lack of elegance to be studiously avoided. Hence few of the literati who visited the Leifeng Pagoda were inclined to evoke the White Snake even though they were thoroughly familiar with the lore. The old drunkard or old monk suited their taste better. They could live with, and relate to, the sedate, sagging old-manlike pagoda ruins, but not the monstrosity, hailing from the theatrical universe, that haunts it.

This is best demonstrated by the Qianlong emperor's response to the pagoda site. Between 1751 and 1784, Qianlong made six tours of inspection to south China. Each time, the itinerary included West Lake, including the Leifeng Pagoda site. To entertain the emperor during his long boat trip, salt merchants recruited a group of celebrated actors and commissioned a new adaptation of the Leifeng Pagoda, which resulted in Fang Chengpei's Romance of the Leifeng Pagoda (1771). A stage was then constructed on two boats that preceded the emperor's boat, facing the emperor. Qianlong was thus able to watch the play on his way to its real site. He thoroughly enjoyed it.[67] His visits to the Leifeng Pagoda led to a total of eight poems, six on the view of the pagoda at sunset and two on the pagoda itself. The drama of the White Snake woman must have been fresh in his mind when he composed these poems. Yet none mentions it. Two themes run through his poems: a eulogy of the sunset view, and a lament over the 'ancient site' that tells of the 'rise and decline' of an imperial cause. In other words, Qianlong was just churning out poems that utilized two time-honored topoi associated with famous scenic sites and ruins. Had Qianlong written the poems in his study, he might have been under less pressure and turned out something better than these run-of-the-mill literary exercises. The palpable immediacy of the ruins must have made him realize the inadequacy of the topoi he used to measure up to the striking spectacle of the real. The supernatural riot conjured up on the stage, to which he had been freshly exposed, must have tempted him. Yet long ingrained in the traditional literati culture, Qianlong did not have the boldness to play with the themes provided by the dramatists. At one point, he nearly did: '[The pagoda site] demonstrates that all appearances (se 色) are emptiness (kong 空), such as this one.'[68] The interplay between appearances and emptiness is a commonplace and is the refrain chanted as the moral at the close of the Leifeng Pagoda. The shadow of the snake woman apparently lurks behind the line, yet Qianlong reverted to the less disquieting images of 'the pristine moonlight shadows' spreading up 'lattice windows.' The colossal ruin strained this old lyrical topos, and Qianlong resorted to conventions of the huaigu (contemplating the ancient), treating the ruin literally as an ancient site of the Wu-Yue imperial cause. This is a bungling effort nonetheless. It is generically unconventional to seize on a pagoda ruin as a vestige of an imperial cause,[69] and very few Chinese literati have considered the Leifeng site fitting for huaigu, for the inept Wu-Yue kingdom had never been seen as worthy of lamentation: one sighs only for those causes that follow periods of rise, those whose fall is all the more emotionally and cognitively unsettling.

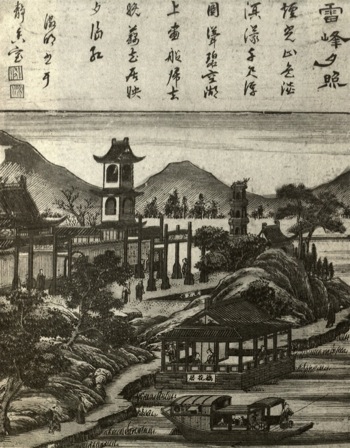

Fig.12 Anonymous, Leifeng in Evening Glow [poem by Yin Tinggao (13th c.)]. 341 x 266. Woodblock print from Suzhou. 18th century. Tenri University Library, Japan. After Machida shiritsu kokusai hanga bijutsukan, comp., Chugoku no yofoga ten: Minmatsu kara Shin jidai no kaiga, hanga, sashiebon (Tokyo: Machida shiritsu kokusai hanga bijutsukan, 1995), p. 379, pl.108.

The same site struck an Englishman in a different way. On November 14, 1794, Lord Macartney, the English ambassador to Qianlong's court, 'travelled in a palanquin... in passing through the city' of Hangzhou. The entire West Lake struck him as 'very beautiful', yet only one feature, one single landmark, leaped out and found its way onto his diary: the Leifeng Pagoda:

On one side of the lake is a pagoda in ruins, which forms a remarkable fine object. It is octagonal, built of fine hewn stone, red and yellow, of four entire stories besides the top, which was moldering away from age. Very large trees were growing out of the cornices. It was about two hundred feet high. It is called the Tower of the Thundering Winds, to whom it would seem to have been dedicated, and is supposed to be two thousand five years old.[70]

It is no surprise that the pagoda ruin should appeal to the taste of the British Ambassador, whose sensibility had been finetuned by the contemporary English preoccupation with moss-grown ruins with their Gothic overtones.[71] The Chinese emperor, however, would not take the ruin on its own terms and see it as it is; he preferred what it once was. In his poems, he insisted that one should not let the present lamentable sight of the pagoda ruin tarnish its former splendor. This discomfort with the ruinous pagoda is reflected in a painting, originally by Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1768) and then copied by Ji Ruinan 輯瑞南, depicting Qianlong's tour of the lake, with the Leifeng Pagoda in the background. Despite the documentary orientation of the painting, the painter restored the pagoda to its imagined pre-fire condition.[Fig.11] Contemporary prints from the Suzhou area betray a similar attitude toward the pagoda.[72] The compositions show a tendency to minimize the role of the Leifeng Pagoda in the sunset view. One, entitled Leifeng in Evening Glow,[Fig.12] combines the picture with a poem, inscribed above the composition. The poem was originally written by Yin Tinggao 尹廷高, a thirteenth-century poet, who described the Leifeng Pagoda before the fire:

The mist-shrouded mountains are blurred in the hazy light,

The thousand-yard tall pagoda alone leans against the sky.

The pleasure boats have all but turned ashore,

Leaving the lonely hill to retain a piece of the sunset red.[73]

The choice of this poem as the inscription suggests a quixotic clinging to the past. The print designer was probably embarrassed by the present state of the pagoda. In the picture, the shabby pagoda is downscaled in the distance, even though this runs the risk of undermining the inscribed poem that celebrates 'the thousand-yard tall pagoda alone lean[ing] against the sky.' The central position usually occupied by the pagoda is here ceded to a bell tower, premised perhaps on the idea that the reverberating bell in the evening air may still retain the old mood of sunset-bathed Leifeng. The discrepancy between the thirteenth-century lyrical vision of the sunset pagoda and the pictorial diminishing of its eighteenth-century remnant demonstrates all too clearly a commonly shared sense of embarrassment, if not dismissal, toward this fire-ravaged monstrosity.

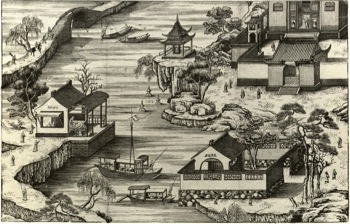

Fig.13 Leifeng in Evening Glow. 344 x 523. Woodblock print from Suzhou. 18th century. Kyoto. private collection. After Machida shiritsu kokusai hanga bijutsukan, comp., Chugoku no yofoga ten: Minmatsu kara Shin jidai no kaiga, hanga, sashiebon (Tokyo: Machida shiritsu kokusai hanga bijutsukan, 1995). p.393. pl.121.

Another Suzhou print of identical style compresses six of the Ten Views into one coherent vista. Although the view of the Leifeng Hill in Evening Glow apparently occupies the high prominence, the print omits the pagoda altogether; in a stroke of visual ingenuity, there is instead an open pavilion sheltering a stele on which is inscribed '[Lei]feng xizhao,' Leifeng in Evening Glow. Long shadows are cast over the water surface toward the east, thereby reinforcing the idea of a sunset view.[Fig.13] Every poem that eulogizes Leifeng in Evening Glow associates it with the pagoda. In fact, the pagoda is the view: 'Each time the sun sets in the west,' writes the author of the West Lake Gazetteer, 'the soaring pagoda casts its long shadow; this view (jing) is unsurpassed.'74 Now, it can be dispensed with, only because it could be an embarrassment to those seeking the picture-perfect view, and their notion of what constitutes a perfect picture and a good view cannot accommodate a monstrosity. The pagoda in its fire-stripped decrepitude makes a mockery of all that is traditionally deemed lyrical, pictorial qualities that make a landscape a 'view'.

To the eighteenth-century emperor and many of his contemporaries, the White Snake lore associated with the Leifeng Pagoda was a monstrosity to be confined to the world of make-believe on the stage; it was unthinkable in relation to the real physical colossus. Yet the stirring demonic matter that roils the stage cannot but cast its shadow over the eerie ruin and tum it into a monstrosity of sorts. Even freed from the association with the tale of the demonic, the pagoda ruin is itself a monstrosity in another sense: it strains the traditional literati's entrenched cognitive stock of tropes and topoi, none of which is adequate to this moldering colossus. That would have to await the arrival of a more modem age, able to take it up unflinchingly, completely on its own terms.

Xu Zhimo, Leifeng Pagoda, and the Modernist topos

At 1:40 P.M. on September 25, 1924, the quiet of West Lake was disturbed by the sudden collapse of the Leifeng Pagoda, which raised a soaring dust column that 'blocked out the sun' and sent clouds of crows and sparrows swarming the sky. It was quite a while before the dust settled. The seven-story edifice was reduced to a mammoth heap of rubble, and only one story remained standing. Soon, the site drew tens and thousands of spectators who combed the ruin for artifacts. Police were called in, and a protective wall was built to keep looters out. Half a month later, some soldiers, allegedly commissioned by a certain Mr. Ju in Beijing, broke in and took away copies of the sutras inside brick tiles. That opened the floodgates. They were followed, some twenty or so days later, by a thousand soldiers who destroyed and plundered what remained. Local peasants followed suit. What was left of the Leifeng Pagoda was 'a heap of yellow earth.'[75]

The crumbling of the pagoda sent a shockwave throughout China and became an absorbing topic of conversations, inquiries, ruminations, and spasms of hand-wringing. For some, the collapse of the pagoda brought an epistemological crisis. It suddenly dawned on people that even the natural scheme of things was subjected to change and decline. For all its arbitrariness as a cultural construct, the Ten Views of West Lake—of which Leifeng in Evening Glow was one—had since the thirteenth century been fossilized into a natural given and presumed to be impervious to change and decay. Now with the tenfold vista suddenly incomplete, the 'natural' landscape seemed to be dented. This realization 'jolted many out of the slumber' that had sustained a dream of 'completeness.'[76] For others, the collapse of the pagoda was an academic topic, for it yielded unexpected archeological treasures. The number of sutras recovered from the ruin was second only to those discovered at Dunhuang two decades earlier. That these woodblock-printed sutras were produced only a century after the invention of woodblock printing highlighted the significance of the discovery.[77] The finding galvanized intense research by distinguished scholars such as Wang Guowei

王國維 and others.[78] To still others, not surprisingly, the collapse was a topic for elegy and spawned a renewed round of nostalgic outpouring in the form of poetry and painting. One painter-poet spoke of his heart 'being pounded'; to his sensitive ears, the reverberating evening bell was 'choking with tears.'[79]

Radical intellectuals, however, reveled in the news of the collapse of the structure, for they saw a larger significance in it beyond the mere crumbling of the pagoda itself. The timing of the collapse was apocalyptically pointed: it occurred at the juncture when China was caught between an imperial past that had just recently ended and an uncertain future of possibilities. Awareness of the temporal disjuncture and anxiety about the transition from the old to the new intensified the perceptions of old buildings and ruins to which the weight of the past was attached. Zhou Zuoren 周作人, still a radical thinker at this time, argued in 1922 that nostalgia for the past was not a good reason for conserving ancient ruins. For him, ruins and historical sites should be landmarks that point to the future instead of the past. The modern travestying of ancient sites, such as Zhejiang cloth merchants' 'vulgarizing' cosmetic touches to the Orchid Pavilion, repelled him. Zhou would rather see the 'original fragmented vestige of dignity.'[80]

Corresponding to the preoccupation with physical ruins were ruins as topoi in discourse. Metaphors of architecture and ruins often framed contentious arguments over the fate of Chinese culture, couched in the stark opposition between the old and the new, past and future, and oppression and liberation. In addressing the tension between traditional China and themodern West, Liang Shuming 梁漱溟 proposed a three-way scheme. He framed it by way of a central architectural metaphor: 'a dilapidated house'. The three major civilizations—China, India, and the West—he argues, would harbor different attitudes toward it. The Western response would be to demolish it and build a new one; the Chinese answer would be to repair it with care; and the Indian attitude, rooted in Buddhist quietism, would be to renounce the desire for housing altogether.[81] Embedded in this rhetoric is a preoccupation with the dialectics of destruction and construction.[82] The ruin topos played into this purpose with renewed relevance. The traditional Chinese meditation on ruins is an understated recollection in tranquility of a past event, at times traumatic. It is premised on a poignant resignation toward the leveling effect of the passage of time, which neutralizes and distances the drama of history, and on a recognition of the permanence of nature, which eclipses all dynasties and enterprises. A ruin is accepted as a larger historical fact; it rarely prompts visions either of willful destruction or of construction, even though a ruined site is perpetually caught in the cycle of decay and physical reconstruction. In the early twentieth century, the ruin topos underwent a change. It spawned visions of what Rose Macauley calls the 'ruin-drama staged perpetually in the human imagination, half of whose whole desire is to build up, while the other half smashes and levels to the earth.'[83]

Macauley's assertion that the 'ruin is always over-stated' may not be always true with regard to traditional Chinese discourse; it certainly obtains with regard to two natives of Zhejiang: Xu Zhimo 徐志摩 (1896-1931) and Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881-1936), the most influential writers of 1920s China to harbor a radical vision. Both took up the Leifeng Pagoda topic and 'overstated' it in Macauley's sense.

Both savored a symbolic triumph in the collapse of the pagoda. On September 17, 1925, one year after the crumbling of the pagoda, Xu wrote the poem 'The Leifeng Pagoda, No Longer to Be Seen'. Seeing the pagoda reduced to 'a deserted colossal grave', the speaker senses an urge to lament but quickly checks it with a self-interrogation: Why should I lament the 'destruction by the passage of time', 'the transfiguration that ought not to be'?

What is it to lament about? This pagoda was oppression; this tomb is burial.

It is better to have burial than oppression.

It is better to have burial than oppression.

Why lament? This pagoda was oppression; this tomb is burial.[84]

By 'burial,' Xu alluded to the White Snake imprisoned under the pagoda. It is easy for the romantic poet known for his defiance of conventional marriage and his passionate pursuit of free love to identify with Madame White. To him, the 'affectionate spirit' suffers only because she took a 'good-for- nothing' lover, and is thereby condemned to the base of the pagoda.[85] Xu was always sensitive to the symbolic overtones of tall structures. During the years of his study in the United States, he came to admire Voltaire and William Godwin—father of Mary Shelley—men who had the courage to 'destroy many false images and to knock down many a tall building' in their times. He became enamored of the writings of Bertrand Russell, whose 'sold shafts of light' had the power of bringing down the Woolworth Building, the imposing 58-story edifice towering over the city of New York, a symbol of the establishment and mighty structures in general.[86] The first time Xu visited the site of the pagoda in 1923, he was struck by its shaky condition: 'The four big brick pillars inside the pagoda have been dismantled to the point where they stand as inverted cones. It looks extremely precarious.' One wonders whether the pillars were not in fact displaced in a different context as organizing tropes for his polemic against conservatism:

Those who mentally embrace the few big pillars left over from ancient times, we call quasi-antiquarians. The posture itself is not laughable. We suspect he is firm in the conviction that the few pillars he clings to are not going to fall. We may surmise that there are indeed a few surviving ancient pillars that are infallible, whether you call them 'cardinal guides' (gang 綱) or 'norms' (chang 常), or rites (li 禮) or ethical tenets (jiao 教), or what have you. At the same time, in fact, the authentic is always mixed with the sham. Those reliable real pillars must be mingled with double their number of phantom pillars, rootless, unreliable, and sham. What if you hug the wrong pillars, taking the sham as the real?[87]

Lu Xun also resented the symbolic implication of the Leifeng Pagoda. He wrote two essays in response to its collapse. The first, 'The Collapse of Leifeng Pagoda', appeared one month after the event. He had seen the pagoda before it collapsed: 'a tottering structure standing out between the lake and the hills, with the setting sun gilding its surroundings.' He was unimpressed.[88] As we have seen, traditional literati normally responded to it as the Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow, one of the Ten Views of West Lake, while ignoring the stormy dramatic romance of the White-Snake woman. Lu Xun, like his contemporary Xu Zhimo, saw the pagoda primarily in connection with the snake-woman romance—related to him by his grandmother—and hence, as a symbol of oppression.[89] 'A monk should stick to chanting his sutras. If the white snake chose to bewitch Xu Xuan, and Xu chose to marry a monster,' observed Lu Xun, 'what business was that of anyone else?' 'Didn't it occur to him [the monk Fahai] that, when he built the pagoda, it was bound to collapse some day? The 'tottering structure' was an eyesore to Lu Xun whose 'only wish... was for Leifeng Pagoda to collapse…. Now that it has collapsed at last, of course every one in the country should be happy.'[90]

It may appear ironic that Xu and Lu should celebrate the collapse of the pagoda, for both were deeply attached to ruins. Their attraction to ruins, however, differed fundamentally from the huaigu topos of the traditional literati. The latter works more by way of temporality and disjuncture: I sigh over a ruin only because it evokes a past that is no more and that is separated from the present world by a gap to which the writer is resigned. To Chinese modernists, such as Xu and Lu, ruins signify primarily by way of spatiality and subversion. For them, ruins beckon not because they evoke a vanished past but because they embody imaginary realms and alternative modes of existence that threaten to take over and eclipse reality.

Xu may have resented the symbolic oppression signified by the Leifeng Pagoda; however, he found the eerie charm of the moonlit pagoda casting its shadow over the lake irresistible. Traditionally, the nearby site of the Three Pagodas was the primary locus amoenus, or 'pleasant place,' that attracted eulogies of moonlit scenes.[91] Xu Zhimo, however, made his dislike of 'the so-called Reflections of the Three Pagodas' explicit. He was, instead, thoroughly enamored of the 'utter serenity of the reflection of the moonlit Leifeng [Pagoda]'. 'For that,' he vowed, 'I would give my life.'[92] After the collapse of the pagoda, he observed with a note of sadness: 'It is rather regrettable that in our south, Leifeng Pagoda remains the only surviving ancient site (guji) cum art work. ...Now the reflection of Leifeng Pagoda has eternally departed from the heart of the lake surface!'[93]

This observation comes out of a most unexpected context: his exposition of John Keats's 'Ode to a Nightingale'. A number of points of contact link Keats' poetic imaginaire to Xu's situation. To begin with, Keats's yearning to leave the world of 'leaden-eyed despairs,' of 'weariness, the fever, and the fret / ...where men sit and hear each other groan'[94] spoke directly to Xu Zhimo, who likewise felt the 'pervasive pain and distress of our time'. Keats listened to a nightingale singing and yearned to 'fade away into the forest dim' in a moonlit night and to fly to some exalted, ethereal state of transcendence. In explicating the poem to his Chinese audience, Xu wrote of the 'purist realm of imagination, the embalmed, enchanted, beautiful, and tranquil state.'[95] In a similar mood, Xu could write about the moonlit Leifeng:

Leifeng Pagoda Under the Moon

I give you a reflection of Leifeng Pagoda,

The sky is dense with cloud dark and white;

I give you the top of Leifeng Pagoda,

The bright moon sheds its light on the bosom of the slumbering lake.

The deep dark night, the lonely pagoda reflection,

The speckled moonlit luminance, the delicate wave shimmerings,

Suppose you and I sail on an uncovered boat,

Suppose you and I create a complete dream world![96]

The relevance of Keats to Xu's world of Leifeng Pagoda does not stop here. In Lamia Keats takes an ancient romance and reworks it into verse. Lycius, a young man of Corinth, encounters a beautiful woman named Lamia. They fall in a 'swooning love' with each other. Their bliss is brought to an abrupt end by the arrival of Apollonius, an old philosopher, who sees through Lamia and proclaims her a 'serpent', upon which, 'with a frightful scream she vanished'. Lycius dies in his marriage robe.[97] The story was first recorded in European literature by Philostratus. Resurfacing in the seventeenth century, it found its way into Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy, which is the source Keats acknowledges. The Lamia story has striking parallels with the Chinese White Snake story.[98] Xu Zhimo was evidently familiar with both the Chinese tale and Keats's famous poem. There were even scholarly inquiries into the connection between the two in academic journals of his time.[99] The Western romantic treatment of a matter familiar to the Chinese inevitably had an impact on the sensibility of someone like Xu who was receptive to Western imagination. Lamia provides a new lens for viewing not only the White Snake romance but, more important for our purpose, the landscape of the Leifeng Pagoda that is the backdrop of the story. The new impulse is the demonic enchantment that suffuses an imaginary landscape with an oneiric quality and an eerie beauty. True, this poetic mood is not alien to Chinese tradition. Yet the long-lasting and ever-deepening Confucian wariness about the demonic has considerably tempered Chinese aesthetic taste over time. By Xu's time, the Chinese imaginary repertoire had been so sterilized and cleansed that the injection of the Keatsian demonic aesthetics had a refreshing impact.

The effect of the demonic enchantment on Xu Zhimo did not hinge entirely on his awareness of Lamia. Keats's poetry is shot through with it. In 'Ode to a Nightingale', which Xu Zhimo knew by heart, the demonically charged landscape is just as striking. Enwrapped in the 'embalmed darkness' of a bower, the speaker envisions 'verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways ' and 'charm'd magic casements... in faery lands forlorn.'[100] Nothing of this was lost on Xu Zhimo, who likened the experience of the ode as 'a child descending into a cool basement, half-terrorized'. In any event, it is apparent that Xu wholeheartedly embraced and internalized the eerie beauty of Keats's poetic world, a conflation of an ethereal transcendent otherness and a haunting demonic enchantment. It was thus inevitable that his poetic meditation on the Leifeng Pagoda departed from the traditional

huaigu topos. The demonic specter that haunted the site in folkloric literature and was largely banished from the literati discourse was welcomed back with a vengeance. Xu described the pagoda as the 'ancient tomb of Madame White,' 'an affectionate demonic enchantress…[buried] deep in the wild grass' (1:168).

It has been thousand and one hundred years

Since she was pitifully clasped under Leifeng Pagoda—

A decaying old pagoda, forlorn, imposing,

Standing alone in the evening bell of Mount South Screen. [I:169]

Elsewhere, he saw the pagoda as a 'desolate colossal grave, with entwining cypresses atop' and 'one-time illusive dream and one-time love' buried underneath. In these poems, we can sense a resonance of Keats ('Forlorn! The very word is like a bell').[101]

The first time Xu visited the pagoda on October 2l, 1923, he was struck by its 'ineffably mysterious grandeur and beauty', which partly derived from its ruinous state. The paths leading to the pagoda were overgrown with brambles. The forlorn sight and site had repelled other visitors. A group of Xu's contemporaries climbed to the top of the Leifeng Hill in 1917 and saw the famed pagoda 'standing in isolation': 'So, this was what they call the Leifeng Pagoda! Underneath it, all the walls and fences were about to crumble. The broken tiles and fragmented bricks were everywhere, making it hard to tread through. The thistles and thorns of the undergrowth kept hooking our clothes. Disappointed, we all left.'[102] Xu, however, was fascinated by the forlorn features of the site. His palanquin-carriers identified two bramble-overgrown tombs nearby the pagoda as those of Xu Xuan and the White Snake woman. Seven or eight mendicant monks in tattered robes, 'with swan-like figures and turtledove-like faces... begged for money while reciting sutras.' A hawker claimed that a yard-long snake he was holding was the Little Green Snake, maid to Madame White, and offered to release it should anyone pay for it. Xu paid twenty cents and 'saw the man tossing the snake into a lotus pond.' He knew that before long 'she would fall into his hands again.' Others would have seen these events as pathetic and laughable. Xu, however, found the experience 'rather poetic.'

The pagoda ruin is indeed a historic site (guji) that dates to the Wu-Yue kingdom. Its association with the popular romance (chuanqi) of snake woman is largely confined to the realm of entertainment and make-believe. Few 'serious' literati would transpose the romance to the actual pagoda site, preferring to leave it as a prop on stage. Xu, however, marries the romance with the physicality of the real pagoda. Early topographic descriptions distinguish between an 'ancient site' (guji) and an 'aberrant site' (guaiji) on the premise that a site cannot be both. Xu made the Leifeng Pagoda site both: it is at once a site heavy with historical memory and enlivened with romantic associations. 'It has been thousand and one hundred years,' he wrote longingly, 'since she [White Snake] was pitifully clasped under Leifeng Pagoda.' Not that he believes this to be an empirical fact, but, as a romantic, he insisted that the fiction of the White Snake take precedence over lackluster reality. 'I would like to become a little demon,' he wrote in his diary, 'in the enchanting shadow of the Leifeng Pagoda, a demon who does not return to the shore, forever. I would! I would!'[103] This refusal to choose between dreaming and waking states characterizes Xu's perceptual mode. Thus in a memorial for Xu Zhimo, Lin Yutang observed: 'Nothing that impinged on his eyes... was the contour of real things. It was invariably the shape of the fantastic constructs of his mind. This man loved to roam; and he saw spirits and demons. Once hearing an oriole, he was startled. He jumped to his feet, exclaiming: this is [Keats'] Nightingale!'[l04]

Next | Previous

Notes to Part II:

[59] For a survey of the historical trend in legitimizing the strange in the late seventeenth century, see Judith T. Zeitlin, Historian of the Strange: Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993), pp.17-25.

[60] Huang Tubi, Leifengta, p.337.

[61] 'Mourning in Front of the Pagoda,' in Fu Xihua, Baishezhuan ji, pp.110-11.

[62] Li Liufang 李流芳, Tanyuanji 檀園集 (Collection of the Sandalwood Garden), YWSQ, 1295: 394.

[63] Waikam Ho, ed., Century of Tung Ch'i-ch'ang (Seattle: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and University of Washington Press, 1992), 2: 104.

[64] The line alludes to a famous Chan-Buddhist motto. The lay Buddhist Pang Yun is reported to have asked Daoyi (709-88): 'What kind of man is he who is not linked with all things?' To which Daoyi replied: 'Wait until at one gulp you can drink up all the water in the West River, and I will tell you' (Fung Yu-lan, A History of Chinese Philosophy, trans. Derk Bodde [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953], 2: 393).

[65] Zhang Dai, Xihu mengxun, p.66.

[66] Ibid., p.4.

[67] Xu Ke 徐珂, comp., Qingbai leichao 清稗類鈔 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1984), I: 341.

[68] JCSZ, p.3702a.

[69] There are, indeed, notable exceptions arising out of special historical circumstances. These include the pagoda at the Linggu Temple, next to the tomb of the Ming founder, and the so-called Porcelain Pagoda at the Bao'en Temple, built by the Yongle emperor: they were associated, after the fall of the Ming, by the loyalists with the Ming dynastic enterprise. I thank Jonathan Hay for bringing these to my attention.

[70] J.L. Cranmer-Byng. ed., An Embassy to China: Being the journal kept by Lord

Macartney during his embassy to the Emperor Ch'ien-lung, 1793-1794 (Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1963), p. 179. Macartney mistook 'Leifengta' as 雷風塔, thereby translating it as 'the Tower of the Thundering Winds.'

[71] See Kenneth Clark, The Gothic Revival: An Essay in the History of Taste (New York: Harper and Row, 1962), pp.46-65.

[72] Most Suzhou prints are undated. Based on a few dated prints of a similar style, these date to the Yongzheng (1723-35) and Qianlong (1736-95) reigns. One telltale sign in the prints is the phrase 'Leifeng in Evening Glow' (Leifeng xizhao 雷峰夕照) instead of the usual 'The Leifeng Pagoda Bathed in West Sunset: a change in the wording made by the Kangxi emperor when he visited the site. Qianlong used Kangxi's phrase in his poem on the view in 1751. However, by 1757, he had reverted to the pre-Kangxi phrase 'Leifeng in Evening Glow.' It is likely therefore that the Suzhou prints here, in following the old phrase, must have been dated to the second half of the eighteenth century. For the dating of the Suzhou prints in general, see Chugoku no yofuga ten: Minmatsu kara Shin jidai no kaiga, hanga, sashiebon (Exhibition of the Western-influenced style in Chinese painting, prints, and illustrated books from Ming to Qing dynasties) (Tokyo: Machida shiritsu kokusai hanga bijutsukan, 1995), p.376.

[73] The print does not reveal the source of the poem. I have been able to identify the late Song-early Yuan poet Yin Tinggao as its author: for the full text of the poem, see JCSZ, p.3918a

[74] Li Wei 李衛 et al., comps., Xihu zhi 西湖志 (Gazetteer of West Lake) (1735

ed.), 3: 32-33.

[75] Tong Danian 童大年, 'Leifengta Huayanjing canshi zhenxing tiba' 雷風塔《華嚴經》殘石真形提拔 (Comment on the fragmented stones with the Flower Garland Sutra from the Leifeng Pagoda): cited in Mei Zhong 梅重 et al., Xihu tianxia jing 西湖天下景 (West Lake: view of the world) (Hangzhou: Zhejiang sheying chubanshe, 1997), p.86; Yu Pingbo, Yu Pingbo sanwen zalun bian, p.116; and A.C. Moule, 'The Lei Feng T'a,' Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 1925: 287.

[76] Shen Fengren, Xihu gujin tan (West Lake: past and present) (Shanghai: Dadong shuju, 1948), p. .

[77] Yu Pingbo, Yu Pingbo sanwen zalun bian, pp.121-22.

[78] Wang Guowei 王國維, 'Xiande kanben Baoqieyin tuoluoni jing ba' 顯德刊本寶篋印陀羅尼經 (Postscript to the Baoqieyin Dharani sutra), in idem, Guantang jilin 觀堂集林 (Shanghai: Shanghai shudian, 1992), 21.22.

[79] Lou Xu 樓虛 'Song to the tune of Yu the Beauty,' colophon to his painting The Leifeng Pagoda: cited in Pan Chenqing 潘臣青, Xihu huaxun 西湖畫尋 (In search of paintings of West Lake) (Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin chubanshe, 1996), p.149.

[80] Zhou Zuoren 周作人, 'Guanyu chongxiu Congtai de shi' 關於重修叢臺的事 (On rebuilding the Cong Terrace) (1922), in idem, Tanhuji 談虎集 (Speaking of tigers: essays) (Shanghai: Beixin shuju, 1928), 2: 463-66.

[81] Guy Alitto, The Last Confucian: Liang Shu-ming and the Chinese Dilemma of Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), p. 83: Jonathan D. Spence,

The Gate of Heavenly Peace: The Chinese and Their Revolution, 1895-1980, p. 208. Italics added.

[82] See Spence, Gate of Heavenly Peace, p.276.

[83] Rose Macaulay, Pleasure of Ruins (London: Thames & Hudson, 1984), p.100.

[84] Xu Zhimo 徐志摩, Xu Zhimo quanji 徐志摩全集 (Complete works of Xu Zhimo) (Hong Kong: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1983), I: 246.

[85] Ibid., p.169.

[86] Spence, Gate of Heavenly Peace, p.191.

[87] Xu Zhimo, 'Shoujiu yu 'wan'jiu' 守舊與'玩'舊 (Holding on to the old and 'playing' with the old), in idem, Xu Zhimo quanji, 3: 2.

[88] Selected Works of Lu Hsun (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1957), 2: 82.

[89] For a convincing demonstration of the impact of Freudian theory on Lu Xun with regard to Lu's perception of the Leifeng Pagoda, see Leo Ou-fan Lee, Voices from the Iron House: A Study of Lu Xun (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), pp.119, 219n21.

[90] Translation from Selected Works of Lu Hsun, 2: 82-84, with slight modifications.

[91] On locus amoenus, see E.R. Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, trans. William R. Trask (New York: Pantheon Books, 1953), pp.192-202; and Michad Leslie, 'Gardens of Eloquence: Rhetoric, Landscape, and Literature in the

English Renaissance,' in Toward a Definition of topos: Approaches to Analogical Reasoning, ed. Lynette Hunter (London: Macmillan, 1991), pp.17-19.

[92] Lu Xiaoman 陸小曼, ed., Zhimo riji 志摩日記 (Zhimo's diary) (Beijing: Shumu wenxian chubanshe, 1992), p. 24.

[93] Xu Zhimo, Xu Zhimo quanji, 3: 65.

[94] John Keats, Complete Poems, ed. Jack Stillinger (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982), p.280.

[95] Xu Zhimo, Xu Zhimo quanji, 3: 65.

[96] Ibid., I: 41-42.

[97] Keats, Complete Poems, pp.342-59.

[98] Their similarity has spawned speculation about a distant and obscure common source, initially oral, not yet identified in Asiatic folklore. See G.R.S. Mead, Apollonius

of Tyana (London, 1901), passim; Takeshiro Kurashi, 'On the Metamorphosis of the Story of the White Snake,' Sino-Indian Studies, 5 (1957): 138-46; and Charles I. Patterson, Jr., The Daemonic in the Poetry of John Keats (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1970), p.185n3. Other scholars attribute the parallel to the workings of archetypes and assume the universal character underlying both narrative traditions; see, e.g., Henry Eckford, 'The 'Lamia' of Keats,' Century Magazine, n.s. 9 (Dec. 1885): 243-50; and E.G. Pettet, On the Poetry of Keats (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1957), pp.215, 229-31. For a most comprehensive study of both Asian and Western sources, see Ting, 'The Holy and the Snake Woman: pp.145-91.

[99] For a discussion of Keats's Lamia in connection with the Chinese White Snake romance, see Qin Nü 秦女 and Ling Yun 凌雲, 'Study of the Romance of White Snake' (in Chinese), Zhong Fa daxue yuekan 中法大學月刊 (Revue de l'université Franco-Chinoise) 2, no.3/4 (1932): 107-24.

[100] Keats, Complete Poems, pp.279-81.

[101] The passage is a familiar one: 'Forlorn! the very word is like a bell / To toll me back from thee to my sole self! / Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well / As she is fam'd to do, deceiving elf./ Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades / Past the near meadows, over the still stream, / Upon the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deep / In the next valley-glades (Keats, Complete Poems, p.281).

[102] Fang Shaozhu 方紹翥, 'Lüxing Hangxian Xihu ji' 旅行杭縣西湖記 (Journal written after a trip to West Lake of Hangxian), in Xin youji huikan 新遊記匯刊 (A collection of new travelogues) (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1920), 1.25.

[103] Xu Zhimo, Xu Zhimo quanji bubian 徐志摩全集補編 (Complete works of

Xu Zhimo: sequel) (Hong Kong: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1993), 4: 6.

[104] Chen Congzhou 陳從周, Xu Zhimo nianpu 徐志摩年譜 (Xu Zhimo: a chronicle) (Shanghai: Shanghai shudian, 1981), p. 76. Lin Yutang here mistakenly attributed Keats's famous Nightingale to Shelley, who is better known for his skylark.

|