|

||||||||||

|

EDITORIALNo. 25, March 2011Wine (jiu 酒) and

|

| I lift my drink and

sing a song for who knows if life be short or long. Man's life is but the morning dew The melancholy my heart begets Who can unravel these woes of mine? Disciples dressed in blue You are the cause Across the bank a deer bleats Honored guests i salute Bright is the moon's spark Thoughts of you from deep inside Stars around the moon are few Flying with no rest No mountain too steep Sages pause when guests call |

曹操《短歌行》

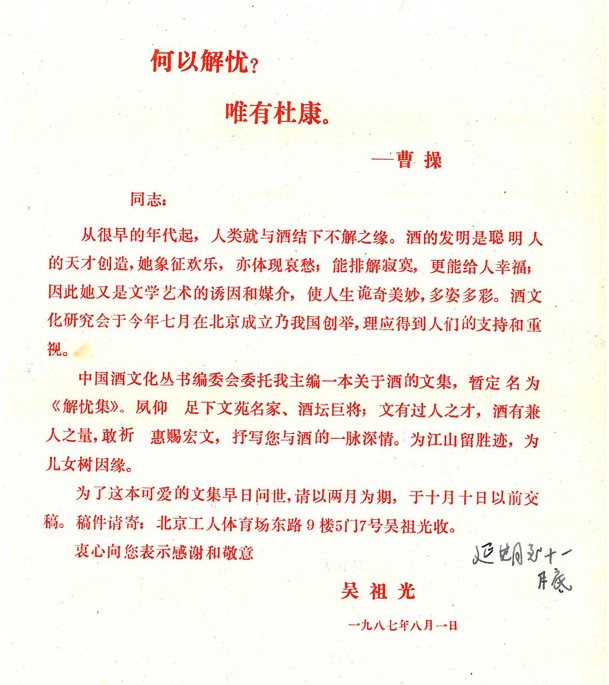

對酒當歌,人生幾何?  Fig.3 The title page of Essays on Dispelling Despondency with the name of the book in Huang Miaozi's hand |

The Layabouts Lodge 二流堂

Fig.4 Tang Yu, the Master of The Layabouts Lodge, in wartime Chongqing. (Source: Tang Yu 唐瑜, Accounts from the Master of The Layabouts Lodge [Erliu Tang zhu jishi 二流堂主纪事], p.249)

In his contribution to Zuguang's book, 'Speaking of a Title', Yang Xianyi would argue that Cao Cao was hardly a man who needed wine to dispel any despondency. He also shares his doubts about the authorship of a poem attributed for centuries to the old warhorse, and suggests instead that it was collective composition. Amidst the well-natured chiding and playful reminiscences of the dark days of High Maoism none of those who wrote for the book in 1987-88 had any idea what the following year would bring, nor what would unfold politically for China in the aftermath of 1989. However, in the spirit of a 'late efflorescence', Wu Zuguang's appeal did join in print many of the remaining members of a unique cultural salon that had originally flourished in wartime Chongqing 重慶 in the early 1940s.

Erliu Tang 二流堂 or The Layabouts Lodge was the name given to a building owned by a wealthy Burmese Chinese known among his friends as A Lang 阿郎, the pet-name of Tang Yu 唐瑜 (1912-2010).[Fig.4] Tang enjoyed a successful career in publishing and film, as well as being able to rely upon the generous support of wealthy relatives outside China. He in turn was unstinting in providing the struggling artistic talents of the wartime Nationalist capital with food and lodging. His house became, avant la lettre, the Chelsea Hotel of the city.

Fig.5 Erliu Tang, The Layabouts Lodge, in Huang Miaozi's hand. (Source: Tang Yu 唐瑜, Accounts from the Master of The Layabouts Lodge, cover image)

On one occasion the unfailingly pro-Communist Party writer Guo Moruo 郭沫若 and Xu Bing 徐冰, the Chongqing-based Party United Front Department representative, visited Tang's artist-packed house; both men were shocked and bemused to find that many of its near one dozen denizens were still in bed. These 'cultural youth' were for the most part men and women involved in theatre and journalism; they slept late and rose even later. Guo used the slang term erliuzi 二流子 ('slouch', 'scoundrel', 'wastrel', 'ne'er-do-well', or 'slacker')—an expression from the Northern Shaanxi 陝北 Communist-base area that had recently become popular[1]—to describe the unruly mob and the name stuck. Thereafter, Tang's house became known as Erliu Tang, The Layabouts Lodge.[Fig.5]

Wu Zuguang and other free-thinking and in fact first-rate talents and minds frequently gathered at Tang Yu's house. These members of The Layabouts Lodge were patriotically minded and increasingly critical of the corrupt and authoritarian rule of the Nationalists. They enjoyed a shared language of jokes, literary allusions and political humour, and over years of friendship, reading and appreciating each other's work, or just through the exchange of doggerel verse or political gossip, they developed their own particular argot. Theirs was indeed like a secret lodge.

We should make no mistake, the members of the Layabouts Lodge were by in large 'progressive' cultural figures, which meant that they were attracted to and eventually actively engaged with the Communist Party during the war years. After all, then and during the Civil War of 1949-49, the Party presented itself a force for democratic renewal and humane modernity in China. In countless public statements, speeches, press reports and editorials, Party leaders emphasized time and again that when in power the Communists would support political pluralism, democracy, freedom of speech and basic rights.[2] It was by this means, and through the tireless work of their 'agents of influence'—intellectuals, artists, charismatic political figures and propagandists—that many members of China's elite were won over to the cause, if not as Communists then at least as fellow travellers. The Party was so successful in convincing countless cultural patriots that it was worthy of their trust that whenever they were given an opportunity key members of this group would remind the Party that it should keep to its end of the bargain and bring democracy and freedom to their country. One of the most prominent and outspoken of these was Wu Zuguang.

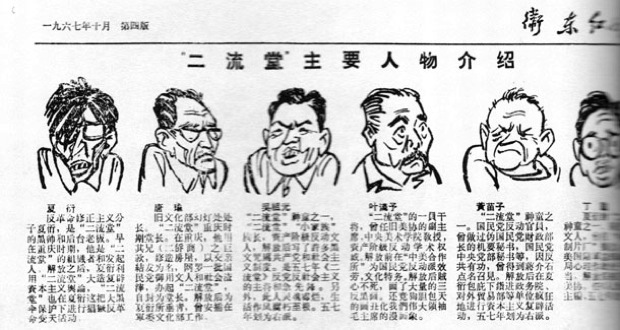

Fig.6 An attack on members of Layabouts Lodge from a Cultural Revolution-era scandal sheet. (Source: Tang Yu 唐瑜, Accounts from the Master of The Layabouts Lodge, p.36)

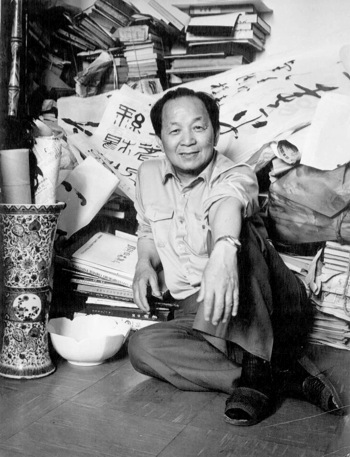

Fig.7 Huang Miaozi in the mid 1980s

Another key member of the old Layabouts Lodge, Huang Miaozi (b.1913), also features in this issue.[Fig.7] His contribution to Zuguang's Essays on Dispelling Despondency is a delightful classical literary homage to Yang Xianyi and his 'spirit'. Miaozi had an early career working for pro-KMT businesses and institutions but later he threw in his lot with the other side. One of China's most note calligraphers he was also famed for his writings on art. In early 2009, Miaozi became the source of unwelcome (and for many old friends heart-rending) controversy when it was claimed that during the 'years of compromise' of the 1960s he had handed over privately exchanged poems and reported conversations he had with his friend the famous liberal poet Nie Gannu 聶紺弩 (1903-86) to the authorities. His accusers declared that this betrayal had contributed to Nie's eventual long years of imprisonment. No convincing evidence of the calumny seems to have been produced,[5] although this distasteful incident does reveal how little is known about the shadowy world of the Chinese personnel file system. Following the Beijing Massacre of 1989, Miaozi and his wife Yu Feng 鬱風 went into self-exile in Brisbane, Australia, eventually returning to China after reaching an accommodation with the authorities.

Complex, and compromising, relations with the Party-state are a feature of the lives of many prominent Chinese literary and cultural figures from even before 1949. Even less famous individuals were constantly caught between personal proclivity and the pressures brought to bear on them by the Party organisation. In Features we also carry an essay in Chinese by Zou Ting 鄒霆 on wine and Yang Xianyi— 'Wine: the Worthy and the Disciple' (Jiu, Jiuxian, Xiao Jiutu 酒、酒仙、小酒徒). A man with a varied literary background Zou eventually became an editor of China Reconstructs (Zhongguo Jianshe 中國建設), a prominent propaganda publication that in its heyday and through its numerous foreign language incarnations was a crucial conduit for the Party to present its ever-changing story to the outside world. Even during the high tide of 'bourgeois liberalisation' in the 1980s for better or worse Lao Zou served the Party line. We recall this by reproducing an essay about a minor editorial incident involving Yang Xianyi and the outspoken journalist Liu Binyan 劉賓雁 from 1986-87 (see 'My Friend the Memory Hole' in Features).[Fig.8] Zou's raffish Chinese essay, written for Wu Zuguang's collection not long after Liu Binyan's disappearance down the memory hole is offered in unsettling contrast to his simultaneous journalistic role as a cog in the massive apparatus known as 'the Party's throat and tongue' (dangde houshe 黨的喉舌). In private Zou remained a delightfully irreverent character.

Two Poems Written While Drunk

Tao Yuanming (365-427CE)

Translated by Gladys and Yang Xianyi

1. My friends appreciate my way of life, And bearing wine pots all together come; We clear the weeds to sit beneath the pine, With several cups of wine we drunk become. When all the elders midst confusion speak, And drinking is from all conventions freed; We do not know if we ourselves exist, And pay to the material world no heed. In carefree drinking thus ourselves forget, For in the wine a deeper truth is set.

2.

—From John Minford and Joseph S.M. Lau, Classical Chinese Literature, An Anthology of Translations, New York: Columbia University Press/Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2000, vol.1, p.512.

There lived a scholar who was fond of wine, But since he had no money could not buy; Sometimes he was provided by his friends With wine, if he their problems would untie. And when the cup was filled he drained it straight, And when advice was asked would not refuse. But sometimes he would not his counsel give, For unjust cause his gift would not abuse. For when a wise man is desired to teach, He will not err by silence or by speech.

飲酒二首 陶淵明

1. 故人賞我趣 ,挈壺相與至。 班荊坐松下 ,數斟已復醉。 父老雜亂言 ,觴酌失行次。 不覺知有我 ,安知物為貴。 悠悠迷所留 ,酒中有深味。

2. 子雲性嗜酒,家貧無由得。 時賴好事人,載醪袪所惑。 觴來為之盡,是諮無不塞。 有時不肯言,豈不在伐國。 仁者用其心,何嘗失顯默。

Le Droit d'Oublier and the Right to Be Remembered

In March 2011, as this issue of China Heritage Quarterly was being prepared, impassioned discussions featured in the media regarding efforts by the European Union to protect individual privacy on the Internet. In particular there were moves afoot to ensure that through legislation people would have the 'right to be forgotten' (le droit d'oublier) if they so chose. That is to say, they would be able to have information related to themselves deleted from websites upon request and to have that request enforced by law.

Fig.8 Liu Binyan and Wang Meng 王蒙, then Minister of Culture, at the November 1986 Jinshan 金山 Conference outside Shanghai

We would argue that in today's China an issue of profound importance for both print and electronic media is how people, incidents, ideas and history itself can be protected so that there is a 'right to be remembered'. Due to the tireless efforts of censors and 'opinion editors' in every part of the information landscape and every nook and cranny of society in the People's Republic, the Party-guided media and publishing industry aims at, to employ a Sino-Orwellian formulation, 'harmonising difference'. International media commentators, writers and scholars comment frequently on the obvious elisions related to controversial figures and ideas in China, but people are less aware that the quirky, the idiosyncratic and the humanly complex aspects of life in China and among its people can similarly be consigned to what Soviet thinkers referred to as 'the memory hole'.

In a world that no longer enjoys the presence of the members of Layabouts Lodge, in a China deprived of the lights of Xianyi and Gladys and so many more of their generation one would imagine that in keeping with the 'prosperous age' (shengshi Zhongguo 盛世中國) of economic bounty there would also be room sufficient to remember and celebrate the stories of these extraordinary individuals, including the aspects of their lives that do not accord comfortably with the prevalent orthodoxies of the Communist Party. This sadly is not the case. Xianyi's outspokenness on the morning of 4 June 1989, to which John Gittings refers in his tribute (see Features, 'Xianyi: In Tribute'), as well as his very public resignation from the Communist Party are expunged from the record. At the time Xianyi said of his public outrage at the Beijing Massacre that, 'If I had done nothing but remain silent, I would feel ashamed.' Now, in death, such silence is enforced and maintained by publishers, online editors and the indefatigable Internet police.[6]

The same is true of Wu Zuguang. His criticisms of the Party's abiding dictatorial ways are, not surprisingly, censored in contemporary China. Accounts of his life, as well as his own work as published on the Mainland continue to distort the record. For example, Zuguang mocked the aged Politburo member and ideologue Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木 for his 1 August 1987 visit to Zuguang's apartment the aim of which was to 'encourage him to quit the Party' (quan qi tui dang 勸其退黨). But in the Bowlderised versions of Zuguang's life produced today, Zuguang's biting remarks about this incident (again, see 'Wu Zuguang: A Disaffected Gentleman' in Features) which was of such importance in the last years of his life are twisted so that he now appears pathetically grateful to the Party for its wisdom in suggesting that he obviously had trouble living up to its demanding standards.[7]

Fig.9 A gathering of members of Layabouts Lodge in the 1990s. Left to right: Wu Zuguang, Huang Miaozi, Tang Yu, Zhang Ding, Ding Cong and Yu Feng. (Source: Tang Yu 唐瑜, Accounts from the Master of The Layabouts Lodge, p.77)

In his episodic memoirs Tang Yu, the master of Erliu Tang, recalls being asked by me in 1983 about the origins and history of this loose gathering of cultural figures.[8] Over the years I have collected material on the group but had little confidence that its story could be written without the kind of archival material that is so obviously lurking in the vaults of the Chinese security organs (for the importance of such information, see Timoth Garton Ash's absorbing account of how he learnt about his own past from the former German Democratic Republic's Stasi files on him, marked simply 'Romeo'[9]). The task will be made even harder by the constant distortion of details and memories by the fact that the 'public record' both in print and on the Chinese Internet offers arrant accounts of vital individuals, comments, incidents and ideas that were so germane to their lives.[10]

What do remain, however, in vast cached yet inaccessible stores, are the voluminous accounts collected by the Party apparat over the decades. Even during the years of post-Maoist liberalization, when the Party line wavered between traditional authoritarianism and the possibility of political reform, gatherings of former members and allies of Erliu Tang may never really have been free of informers or covert 'claws and teeth' (zhuaya 爪牙) of the system. It was always best to speak and act as though everything was on the public record. The personnel and security files form immense Borgesian-style libraries of China's modern history and life. Through successive political movements and purges the files have been painstakingly collected, mountains of material amassed full of coerced statements, depositions, informers' reports, self-criticisms, Party evaluations and the like, forming what the Soviet logician and novelist Aleksandr Zinoviev remarked in his 1982 book Homo Soveticus (Гомо советикус) was the only true literature of socialism: the denunciation.

I recall well the time when, probably in 1979, Xianyi and Gladys came back to their apartment at the Baiwan Zhuang compound where I was staying to share the adventures of the morning over lunch. It turned out that on that day they had been invited to the local police station where they were formally told of their 'rehabilitation' (pingfan 平反). They were to be reassured that the previous ridiculous and groundless accusations made against them covering a range of vile crimes in the past had been officially rejected and overturned. Now they could return to the embrace of the Party-state with a clean slate and renewed enthusiasm. Having read out the formal document pertaining to their cases, the police asked the couple whether they would like to be present when the files containing all of the scandalous libel were destroyed. Gladys said that they had politely declined. Anyway, Xianyi observed with a smirk, he was sure that despite all the po-faced playacting the authorities would have kept a copy 'for future reference'.

Free from Servile Bands

Fig.10 Gladys and Xianyi in their later years

From the dying days of the Cultural Revolution, Xianyi and Gladys' sitting room became the scene of a unique and unforgettable salon, for Chinese and non-Chinese friends and visitors alike. It was also something of an alien realm, a post-colonial 'extra-territorial zone', for although the Yangs were still under constant surveillance, even their past minders, keepers and in some cases oppressors would out of curiosity and wonderment come calling, sometimes sincerely to pay their respects. As time went on and as the shrill nonsense of Maoist revolution faded both from reality and from memory many who had shunned the Yangs in the past, or those who had been given the cheerless task of making their lives a misery, began to sense that what had been of such moment was merely transitory folly, while the world of letters and conversation, understanding and engagement represented by Gladys and Xianyi would outlast them all.[Fig.10]

In his recent essay 'The Happy Life', the novelist and poet David Malouf observes that those who are most happy seem to be the people who have learned to live within limits, to find a compromise between the active and the contemplative life, to strike a balance between the possible and the imaginable.[11] I would like to think that in his life's work, in his relationship with Gladys, through his remarkable friendships, and in his reading and conversation, his poetry and his well-natured humour, Xianyi found just such a happy life. Those who knew him, and were changed by him, carry in themselves gleanings of that quiet happiness always.

In his own contemplation of the search for the secret to contentment in the modern world Malouf quotes a poem by Sir Henry Wotton (1569-1639), diplomat and wit (famous also for his quip that a diplomat was 'an honest man sent to lie abroad for the good of his country'). I can think of no more fitting way to end this short tribute and introduction than by recording Wotton's poem 'The Character of a Happy Life' here:

How happy is he born or taught, That serveth not another's will; Whose armour is his honest thought, And simple truth his highest skill;

Whose passions not his masters are; Whose soul is still prepar'd for death Untied unto the world with care Of princes' grace or vulgar breath;

Who envies none whom chance doth raise,

Or vice; who never understood

The deepest wounds are given by praise,

By rule of state, but not of good;

Who hath his life from rumours freed; Whose conscience is his strong retreat; Whose state can neither flatterers feed, Nor ruins make accusers great;

Who God doth late and early pray, More of his grace than goods to send, And entertains the harmless day With a well-chosen book or friend.

This man is free from servile bands Of hope to rise or fear to fall; Lord of himself, though not of lands; And having nothing, yet hath all.[12]

Notes:

[1] Tang Yu 唐瑜, Accounts from the Master of The Layabouts Lodge (Erliu Tang zhu jishi 二流堂主纪事), Beijing: Joint Publishing, 2005 (北京: 生活·读书·新知三联书店). The dialect expression 'erliuzi' had been popularized among 'progressive' cultural figures and others since it was used in the 1943 yangge-play 秧歌剧 'Brother and Sister Reclaim the Wasteland' (Xiongmei kai huang 兄妹开荒) written by Wang Dahua 王大化 and Li Bo 李波 and performed in the Communist-base area at Yan'an, although it was also published in the Chongqing press.

[2] Collected in Xiao Shu 笑蜀, ed., History Bespoken—solemn promises made half a century ago (Lishide xiansheng—bange shijiqiande zhuangyan chengnuo 历史的先声——半个世纪前的庄严承诺), Shantou: Shantou Daxue, 1999. This book was published to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, but was immediately banned. Nonetheless, it is now available in various downloadable online guises.

[3] Mao Zedong, 'Snow, to the Tune of Spring in Qinyuan',《雪,沁園春》. The poem was published under Mao's original name, Mao Runzhi. In October 1945, Mao had a copy of the poem sent to his old acquaintance in Chongqing, Liu Yazi 柳亞子. It was published on 4 November 1945 in the evening supplement of the left-leaning newspaper New Citizen (Xinmin Bao 新民報) and immediately reprinted widely. For more on this, see my study 'For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone—was Mao Zedong a New Emperor?', in Timothy Cheek, ed., A Critical Introduction to Mao Zedong, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp.243-72.

[4] The idea of alternative Layabouts Lodges continued into the 1980s. I was fortunate enough to be present at the Yang's apartment for the first post-Cultural Revolution gathering of some surviving members of the original Erliu Tang in the late 1970s (and again for many other rowdy conversations, meals and drinking sessions thereafter in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong), and I was able to introduce the Taiwan song-writer Hou Dejian 侯德健 to this world after his 'defection' to the mainland in 1983. Later we created for a while our own 'Little Layabouts Lodge' (Xiao Erliu Tang) at Xianyi and Gladys' apartment. This included Linda Jaivin, Richard Rigby and his wife Tai-fang, all of whom were also friendly with Wu Zuguang, Huang Miaozi, Ding Cong, Shen Jun, and many other old 'layabouts'. For details, see Hou's oral history interview about this and his thoughts on the passing of Yang Xianyi, see 'Flush My Ashes Down the Toilet' (Ba guhui daodao choushui matong—Yang Xianyi er san shi 把骨灰倒到抽水马桶——杨宪益二三事), online at: http://blog.stnn.cc/rain804/Efp_Bl_1002725323.aspx.

[5] The accusations were made on the basis of a lengthy account published by Yu Zhen 寓真 on the fate of Nie Gannu—'Nie Gannu's Criminal File' (Nie Gannu xingshi dang'an 聂绀弩刑事档案) in early 2009 and then amplified with a measure of histrionics by the well-known memorialist Zhang Yihe 章怡和 in her 'Who Sent Nie Gannu to Gaol?' (Shui ba Nie Gannu songjinle jianyu? 谁把聂绀弩送进了监狱?), online at: http://baike.baidu.com/view/115439.htm . The controversy continued into 2010 without the libel against Miaozi being substantiated. See, for instance, Ding Dong's 丁东 1 January 2010 article 'Huang Miaozi yisi gaomi, Nie Gannu zhaoran hanyuan' 黄苗子疑似告密 聂绀弩昭然含冤< in Nanfang Dushi Bao 南方都市报, online at: http://nf.nfdaily.cn/nfdsb/content/2010-01/11/content_8003535.htm. This incident has led some commentators to attempt to explain the exceptional circumstance of Chinese revolutionary fervour—and the proletarian dictatorship—that led many people to betray friends and family. It is as though the Party's ongoing war against its own citizens—the use of forced confessions, secret reports, surveillance, police and state security intimidation, framed charges, as well as psychological terror—has somehow come to an end.

[6] See, for example, the online entry at: http://baike.baidu.com/view/247261.htm

[7] See, for instance, the online review at: http://www.newgxu.cn/html/2006-04/29878.htm

[8] Tang Yu, Accounts from the Master of The Layabouts Lodge, p.16.

[9] See Timothy Garton Ash, The File, A Personal History, London: HarperCollinsPublishers, 1997.

[10] In Hungary there have been recent moves initiated by the post-socialist-era government to dispose of such archives altogether. As the authors of an online petition launched to protest against this plan put it:

The Government of Hungary plans to pass a law allowing for the removal and destruction of original archival documents recounting the history of the communist secret police during the previous regime, as officials believe that these papers are the 'immoral documents of an immoral regime.' These archival documents are irreplaceable and once they are destroyed, Hungarian historians will no longer be able to uncover the activities of state security agents during the communist period. I support the preservation of Hungary's historical record, access to historians, researchers, students and future generations and I do not believe that government officials have the right to destroy archival documents that they deem to be 'immoral.'

See the 'Save Hungary's Archives' online petition, at: http://hungarianarchives.com/the-petition/ Thanks to my colleague Philip Taylor for bringing this petition to my attention.

[11] David Malouf, The Happy Life—The Search for Contentment in the Modern World, Quarterly Essay, Issue 41 (2011): 5 & 54-55.

[12] Quoted in Malouf, The Happy Life, pp.3-4.