|

|||||||||||

|

FEATURESSichuan Teahouses:

|

| Table of Contents | |

| The City, Teahouses, and Everyday Culture | 1 |

| Part One. The Teahouse | |

| 1. A Small Business | 27 |

| 2. The Teahouse Guild | 57 |

| 3. Labor and Workplace Culture | 84 |

| Part Two. Teahouse Life | |

| 4. Public Life | 113 |

| 5. Entertainment | 135 |

| 6. All Walks of Life | 167 |

| Part Three. Teahouse Politics | |

| 7. Conflicts in Public | 203 |

| 8. A Political Site | 224 |

| Conclusion | |

| The Triumph of Small Business and Everyday Culture | 249 |

The political uncertainty during this period was clearly reflected in teahouse life, and especially in the daily conversations found there. Although talk on any topic imaginable flowed freely every moment that every teahouse was open, there are few records of specific conversations. However, journalists recorded what they heard in the teahouse in a few newspaper accounts. Some teahouse conversations might have political implications even if they were not overtly political. Here is a random conversation between two people in 1917:

Man A: The Chinese people and the imperial court respected chastity for thousands of years. Therefore, people everywhere praised chastity. However, after the Republic was established, chastity was no longer emphasized, and social customs and people's minds became degraded.Man B: I disagree. In the past, people paid attention to chastity, but now they respect native places. For example, in 1913, nearly everyone claimed to be from Sichuan on their business cards, while in 1914 everyone denied having Sichuan origins. In 1916, though, after the Republic was restored, their business cards again showed that they were Sichuan natives. But, today they all say they are from outside Sichuan. This is a proof that scholars and officials emphasize native places, but which one constantly changes, depending on what is more advantageous.

Man A: A person's native place constantly changes, and nobody knows his real native place. As you have just said, no scholars or officials have a true native place. Our country has scorned liars for thousands of years.[18]

Here the discussion was ostensibly about native places, but it implied that politicians were dishonest. During the early Republican era, people in Sichuan played a more active role on the national political stage. When politicians from Sichuan had power in the central government, the province was highly regarded; otherwise, people ignored it. These conversationalists also believed that values had been degraded, because society had abandoned its reverence for chastity. As we know, in traditional China a woman without chastity was considered a 'disgrace', but this conversation implied that politicians had lost their 'chastity' and become shameless 'liars'.

The more important information we may get from this conversation is the anxiety of losing a cultural identity in the face of constant political struggle and the transition of power. One's native place was a crucial factor for Chengdu's residents, underscoring virtually every aspect of society, economics, and politics and tying people to their cultural roots. This legacy could bring people together to survive in a new environment and help them resist other cultures. After the fall of the Qing, however, the politicians and elites found that the native place could be used as a tool for political gain. The notion of native place began to change although it was still important. This conversation regarding native place in the teahouse reveals people's bewilderment and dissatisfaction regarding the chaotic situation in the early Republican period.

Teahouse-goers not only chatted and gossiped about the minutiae of daily life but also complained about their hardships and expressed anger at the endless political power struggles and corrupt government, along with their opinions about what should be done. Here is a snippet of a conversation between two elderly men:

Man A: Have you noticed recently how everything is new: a new world, new trends, new knowledge, and a new vocabulary? Although we will not follow these new things, we do not have the old ones, either.Man B: In my opinion, they're just boasting wildly. They are only fooling inexperienced youngsters. Any person who has a mind will know they are boasting and cheating. Haven't people as old as you and I seen enough? The happiness promised in 1911 has not reached us. Do you remember the idea of no taxes? Now taxes have to be paid several years in advance. As for freedom, you were scared when you lived in your big house in the country and moved to the capital city. You do not dare to go back home. Are you free? I am tired of the wonderful promises.[19]

It is necessary to look at the historical context of this conversation. This dialogue took place in 1922, when the New Cultural Movement was under way and many new ideas and new consumer goods had recently appeared, including burgeoning new material culture, which caused a rift between Westernized elites and conservatives. Obviously, this conversation was between two conservatives who disliked new things. From this snippet, we find that they opposed the new because in their experience new things brought false promises; they looked good on the outside, but were rotten inside. They remembered the disappointment and hardships of their own experience after the 1911 Revolution and did not feel secure. The promise of the revolution was never realized and the situation only worsened. People lived in a more dangerous world, paid more in taxes, and were not free. Therefore, these men simply blamed their suffering on the advent of the new. Their conversation also hints at their feelings of hopelessness; on the one hand, they resisted the new, but on the other hand, they could not rely on the old traditions either, because the revolution and the New Cultural Movement had destroyed that way of life. At the same time, they expressed their feelings of superiority and their scorn for people who admired the new by emphasizing their social experiences, akin to the so-called spiritual (or psychological) victory that Lu Xun ridicules in his novella The True Story of Ah Q.[20]

The warlord government also sought to control the teahouse. The regulations issued in the early Republican era dealt only with teahouse theaters and performances; the first comprehensive regulations were not issued until 1932.[21] In the late spring of that year, the municipal government issued 'five restrictions', which addressed sanitation in particular but also dealt with gambling. In 1935, the local government issued so-called restrictions for 'preventing incidents that endanger the public.' The new rules allowed only one teahouse in each park, leading to the closure of some teahouses in high-density areas; the remaining teahouses could be open only six hours per day, and only during the morning and at night, and had to close during weekends.[22] These new rules were a reflection of the government's radical and growing concern about the social issues embodied in teahouse culture. There is no evidence that these new regulations were completely enforced. Enforcement would have been disastrous for teahouse workers who faced losing their jobs or who would no longer had been able to make a living. There is also no evidence of a significant decrease in the hours of operation; teahouses still were usually open fifteen to sixteen hours a day. Also, the number of teahouses in Chengdu not only did not decrease in 1936, but actually increased from 599 to 640. The fact that the regulations were ineffective reveals the tenacity of local customs and teahouse culture in resisting attacks by the state.

The Politics of Resistance (1937-1945): 'The Fate of the Nation and Tea Drinking'

The War of Resistance (1937-45) brought Sichuan and Chengdu onto the central stage in national politics. The Nationalist government's move to Chongqing had a profound impact on Chengdu and the relationship between Sichuan and the central government.[23] Many offices of the central government and other provincial governments, social and cultural organizations, schools, and factories moved to Chengdu. A huge number of refugees flooded the city, bringing many new cultural elements with them.[24] The War of Resistance brought politics into teahouses to an unprecedented degree. Social groups and government officials used teahouses to spread propaganda, displaying slogans, posters, and public notices, and overseeing performances and public meetings related to the resistance effort and patriotism. Teahouses actually became a stage for 'saving the country'. Discussions focused on the war, where people could learn the latest news from the frontlines, as well as stories about the resistance, the ruthlessness of the Japanese invaders, and wartime tragedies. Although people still went to the teahouse, an activity still criticized by elites and the government, they could not escape the impact of the war there and were inevitably drawn onto a political stage.

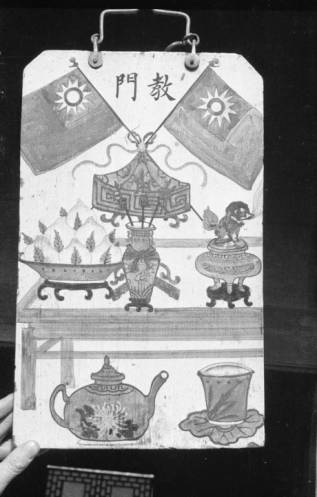

Fig.2 Sign for tea shop with Chinese Nationalist flags, 1930s (Photograph: Harrison Forman. From the American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.)

In a letter to a friend, Zhou Wen described what he saw when he arrived in Chengdu in the late 1930s, when the 'movement for saving the country from crisis' was at its highest point. He describes a group of students in a teahouse carrying flags, with one intensely emotional student standing on a chair and giving a speech as all of the patrons listened. Yet Zhou also found that the war did not seem to change daily life much; just a few days later, he saw people passing through the streets beating drums to advertise performances, and noted that the theaters were still crowded. Zhou was not the only one to comment on this phenomenon. A report titled 'Chengdu under the Microscope' (Xianweijing xia zhi Chengdu) criticized residents for living lives of leisure at teahouses and theaters when the whole nation was caught up in bloody battles with the Japanese. It condemned Chengdu as a 'grotesque and gaudy society' (guangguai luli de shehui). For a period, the government tried to 'regulate wartime life' and generated a discussion that linked the 'fate of the nation to tea drinking' (chicha yu guoyun).[25] Zhou and the author of the report might have seen only the surface of Chengdu society; in fact, the war inevitably affected many aspects of daily life. Although people still frequented teahouses and theaters, the kinds of performances they watched might have already changed. For example, the editor of the publication New Chengdu (Xin Chengdu) said that 'in the past, storytellers' language was licentious and plots were bizarre, which unconsciously corrupted the thoughts and behaviors of the masses.' After the Japanese aggression, storytellers still used well-known materials as the basis for their stories, but inserted patriotic and anti-Japanese themes.[26]

In 1941 a critic condemned the so-called Chengdu phenomenon (Chengdu xianxiang) in which central areas such as Warm Spring Road and Main Mansion Street had more than ten teahouses, all crowded day and night. The author criticized some 'bored and idle people' (baixiangde ren) for sitting in a teahouse all day 'without rhyme or reason.' The writer observed that 'teahouses have recently become an unusual place, where waitresses publicly flirt with customers and even charge four to five times more for tea served in private rooms.' Another article also condemned the prosperous entertainment trade during an era of rampant inflation; people wasted time and money on entertainment when they should be frugal.[27] In 1942, the article 'Chatting about Chengdu' (Xianhua Rongcheng) described the city as not appearing to be in a country at war; people still flocked to the splendid shops, entertainment venues, and teahouses. The population increase meant that these places emerged like 'bamboo shoots after a spring rain', which elites lamented during the national crisis. Another article quoted Chiang Kai-shek as saying that 'the Chinese revolution would have been successful if people had used the time they spent in the teahouse [to pursue] the goals of the revolution.' Many elites thought that teahouses reflected the 'inertia' of people 'who have nothing to do and stay at the teahouse for the entire day'. New Chengdu claimed that these patrons 'kill time in the teahouse, telling stories from ancient and modern times, commenting on society, playing chess, gambling, criticizing public figures, and gossiping about private matters and secrets of the boudoir.' The author wondered, 'How could there be so many idlers in this land who spend their money while doing nothing?'[28] As discussed earlier, the teahouse was multifunctional, and these criticisms focus only on the pursuit of leisure in an effort to make life in the teahouse seem diametrically opposed to patriotic pursuits.

The government tightly controlled public entertainment and tried to shape public perceptions during the war by seeking to use teahouses as places of wartime education, bringing innovations to storytelling, providing new books and newspapers, putting new pictures and slogans on the wall, and facilitating 'patriotic' forms of entertainment. The government required plays to include some patriotic and anti-Japanese terms and content even though the old genres and materials could be still used.[29] A new organization called the Temporary Instruction Committee of the Chinese Nationalist Party for People's Organizations in Chengdu (Zhongguo Guomindang Chengdu shi renmin tuanti linshi zhidao weiyuanhui) was responsible for examining scripts, some of which are still available in the archives and reveal how politics entered this facet of public life. I have found twelve scripts, all of which focus on the war. Some recall the history of Japanese aggression against China; some praise the brave resistance movement; some commemorate the heroes who lost their lives on the battlefield; some express yearning for the lost motherland; some list Japanese crimes committed in China; some bemoan the nation's sad situation; and some recount bloody battles. The kinds of performances varied, and included storytelling and folk songs. The powerful contents and language were intended to wake up and mobilize audience members.[30]

For example, 'Recovering the Motherland' (Huan wo heshan) describes China's beauty, vast territory, rich natural resources, long history, and wonderful culture. The calligraphy of the four characters huan wo he shan written by the Chinese national hero Yue Fei during the Song era was well-known and could be found throughout the country. The use of these characters in the title had a powerful influence on people's hearts and minds.[31] 'Exposing Traitors' (Hanjian timing) denounced the crimes of the Japanese invaders and named eight traitors, exposing them to public shame and adding that there were too many traitors to name individually. This program also tells how they became traitors. Another script with a similar topic, titled 'The Fate of Traitors' (Hanjiande xiachang), warned that 'the heads and bodies of traitors would fall apart if they are caught' and their families would be implicated in their crimes, not only losing their property but also permanently tarnishing their reputation. It cautioned people to avoid such a tragic fate.[32] These scripts used rhymes and lyrics full of political ideas, unlike the traditional style of popular entertainment. These materials targeting the Japanese or traitors obviously met the government's need for a powerful tool of propaganda, which became part of the wartime political culture. Without question, they played an active role in mobilizing people to join the movement to save the country.

Of course, one of the motivations behind these patriotic programs was to promote business, and the theaters and entertainers knew how to deal with the government for survival. In 1939, folksinger Wang Qingyun applied for a permit to perform folk songs in the Pleasant Wind (Huifeng) Teahouse. He claimed that he wanted to 'spread propaganda to support the government' in the War of Resistance. He promised not to perform any 'lecherous songs' but to 'wake people up to mobilize the nation'. He said that 'the final victory must be ours, and we must strongly support Chiang Kai-shek and struggle until the end.' In 1941, three people from Jiangsu requested permission to perform operas, claiming that the Nanjing National Opera Theater (Nanjing guoju shuchang) promoted 'noble entertainment' and helped 'change social customs'. They said that they had witnessed the Japanese invasion and the killing of Chinese, and that it was imperative that anyone who had 'blood and breath' should fight the invaders and recover the stolen land, and that their performance could inspire patriotism and mobilize the masses behind the frontlines.[33]

In 1941, the government ordered all teahouses to purchase portraits of Sun Yat-sen and other Nationalist Party leaders and to prepare space for a lectern, blackboard, a party flag, and national flag. The Teahouse Guild issued a deadline for satisfying this new rule 'in order to avoid investigations by the municipal government and trouble for teahouses that do not have these items.'[34] The military was also involved in wartime propaganda. The military's division headquarters inspected the eleven teahouses on the six streets that made up the Imperial City district for these items. When it was found that none of the teahouses was in compliance, Mayor Yu issued an order to the president of the Teahouse Guild that this equipment was mandatory and that the guild should require all teahouses to meet the regulation.[35] The executive committee of the GMD in Sichuan enacted a Plan of Propaganda in Teahouses (Chaguan xuanchuan shishi jihua), issued by the mayor of Chengdu, which stated that the authorities regarded teahouses as an important arena for propaganda. Under the plan, the 640 or so teahouses in Chengdu were divided into three classes, each of which had different requirements for propaganda.[36]

The government even dictated the messages to be put on the blackboards in each teahouse. A Provincial Mobilization Committee (Sheng dongyuan weiyuanhui) was established and issued a weekly 'summary of current news' for display. An example of these summaries had three pieces of news: a two-line update on the war in Europe; a longer description of the Chinese victory in battles in southern Hubei and northern Hunan, which told how many Japanese were killed and wounded; and a item about diplomacy, such as that China had signed an agreement for a loan of five million pounds from Britain. This example also included one sentence about diplomatic problems caused by the United States' refusal to sign a treaty of nonaggression with Japan.[37] From these passages, we see that the government focused on positive news to promote patriotism and inspire optimism.

The government also asked each police district to set up a large, well financed, and centrally located 'model' teahouse as an example for all teahouses in the district. These teahouses had a simple platform for propaganda, which included newspapers and posters, a radio or record player, and maps of Sichuan and the world. The rule also gave nine categories of slogans to be put on the wall: uprooting traitors, military service, transportation, air defense, economizing and saving, raising money, 'general spiritual mobilization', the New Life Movement, and the 'Citizens' Pledge'. In the category of 'uprooting traitors', the government wanted people to follow the government's policies, carry out the orders of the military, and destroy Wang Jingwei's puppet regime. Through propaganda the government encouraged people to support military service and accept that 'avoiding military service is the most shameful action'. It wanted people to believe that 'the War of Resistance can be won if everyone joins the army', and that giving favorable treatment to servicemen's families and serving in the military were 'citizens' obligations'.[38]

In the category of slogans, the government gave specific guidelines about what people should know and do.[39] While the government mobilized people, it also tried diligently to control people's thoughts and ideas in the name of the national interest. A so-called general spiritual mobilization was conducted to promote ideas such as the state and nation should be supreme, 'selfishness' and 'different and wrong thoughts' should be overcome, and so on. Whereas the 'general spiritual mobilization' was aimed at mind control, the New Life Movement targeted behavior. It applied Confucian doctrines such as 'the rite is a serious principle', 'the righteous face death bravely', and 'a sense of honor is a struggle on a grand and spectacular scale'.[40] Thus, the government used traditional values to connect daily life with national current affairs. The government required all teahouses to post a 'Citizens' Pledge' (Guomin gongyue) as part of wartime propaganda. The pledge had twelve items, requiring citizens to never: violate the Three Principles of the People; violate government regulations; violate the interests of the country and the nation; surrender to the enemy; join traitorous organizations; serve in the armies of enemies and traitors; help enemies and traitors; collect information for enemies and traitors; work for enemies and traitors; use the currencies of the banks of enemies and traitors; buy goods from enemies and traitors; and sell grain or other goods to enemies and traitors. In addition, government regulations required all teahouses to provide government-selected books and newspapers. These books covered many topics, such as praise of war heroes and members of the resistance, condemnation of traitors, mobilization, and the ideology of the Nationalists, as well as anti-Communist Party sentiments.[41]

As the war became a major focus, the government adopted a policy of suppressing all criticism of state power and its representatives. In 1940, for example, the government asked the Teahouse Guild to 'stay on high alert' for 120 students from the Resistance University of Northern Shaanxi (Shanbei kangda) who were coming to Chengdu and Chongqing.[42] The Chinese Communist Party established the university to cultivate leaders. Therefore, the students' arrival concerned the local government, which tried to limit their activities. In the political atmosphere of that time, teahouse employees had to work with the police to enforce local 'security'. In the same year, the police claimed that some traitors and hooligans plotted their activities in teahouses and demanded that the Teahouse Guild provide 'secret reports' on them. The guild had no choice but to cooperate. The government used the term 'traitors' loosely during wartime, frequently applying it to anyone who spoke out against the government. For example, the government defined 'anyone who damages government regulations' as 'a traitor' and demanded 'cleaning out traitors and strengthening the rear area of defense'.[43]

It is obvious that government control over the teahouse caused tremendous resentment. In 1942, the West China Evening News (Huaxi wanbao) published a satirical essay by Ju Ge describing a so-called ideal teahouse (lixiang chaguan) as a 'municipal teahouse' in the heart of the city. The teahouse should have a director and associate director, and all customers should follow their instructions. The teahouse was to serve only Chinese tea, and the quantity of tea leaves in each bowl should be standardized: two millimeters per bowl of green tea, five millimeters for red tea, and three pieces for chrysanthemum tea. There was no limitation on the number of times a bowl could be refilled, but the quantity of water should not exceed 0.5 sheng (about 0.56 quart); customers who weighed more than sixty kilograms or had walked more than two kilometers under the hot sun could request 0.75 sheng. The teahouse should be open from six to seven am, from noon to one pm, from four to five pm, and from nine to ten pm. Patrons who stayed longer than two hours would be punished for wasting time. A teahouse-goer had to get a 'card for drinking tea in the teahouse' (yincha zheng) that certified that he was at least twenty years old and employed, and had received approval from the authorities to patronize the teahouse, including for the reason that his home was too small to accommodate tea drinking. Patrons would be required to dress formally, to 'straighten their clothes and sit properly', and to sip tea slowly. 'Bizarre clothes', 'exposing the neck and shoulders', 'whispering', 'yelling', and especially 'loud talking' would be prohibited. All patrons would be required to be at the teahouse at a certain time, and would not be allowed to enter late or leave early. Before drinking, all patrons would be required to stand up and then be seated. Reading newspapers and playing chess would be forbidden. The teahouse should have a radio, which would be tuned only to certain programs of the Central Broadcasting Station, such as news and market information. All patrons would be required to exit the teahouse by marching in single file.[44] The author is deliberately mocking the teahouse regulations, such as basing the quantity of boiled water on a patron's weight and requiring patrons to enter and leave at the same time, and so on. The 'ideal teahouse' he described is more like a military camp, which reflected people's dissatisfaction with increasing government control.

Never before had there been such large-scale distribution of government propaganda. This movement was well organized and highly controlled. Obviously, teahouses became a 'battlefield' in the government's 'war' for control. In teahouses, patrons could see and hear only what the government wanted them to see and to hear. We can only imagine the political environment and atmosphere created by those new dramas and the portraits, slogans, and pledges that were posted on the walls. Thus, under its wartime propaganda, the Nationalist Party successfully extended its political control into public space and public life. On the surface, teahouse life did not appear much changed, but to a great extent, the core of teahouse life was altered by the domination of the national crisis and political orientation.[45]

In March 1945, on the eve of victory against the Japanese, the provincial government enacted the Regulations on Teahouses in Sichuan (Sichuan sheng guanli chaguan banfa), which covered eleven issues ranging from the location of teahouses to hygiene. Under these rules, all teahouses had to be registered, and the number of teahouses was to be gradually reduced in areas where supply exceeded demand. Furthermore, the new rules prohibited the hiring of waitresses, bringing an abrupt end to the short history of women employees. The regulations forbade some services that had been offered for decades, including haircuts and pedicures, for reasons of hygiene. The regulations also brought new force to bear on the ban on certain activities, such as gambling and the singing of 'licentious' songs, that had been long been ignored. Some trends, including the private 'family tearooms' that emerged in the late-Qing era, were also outlawed.[46]

The opportunity to speak freely was an attraction of the teahouse but this freedom was often challenged by the government, which used its power to suppress people who expressed political ideas and criticized the authorities. Discussing politics in a teahouse was risky. The police and the government could use whatever was said in public against the speaker; some people were imprisoned for expressing their political views. The government commonly planted secret agents in teahouses to eavesdrop. Those who dared publicly criticize the government were harshly punished, which became a means of suppressing dissent. The teahouse also was implicated, even to the point of being forced to close. That is why the teahouse proprietor in Wen Yiduo's song in the epigraph to this chapter begged patrons not to discuss sensitive topics. People were afraid to speak freely.

'Do Not Talk about National Affairs'

According to Yu Xi's essay 'Teahouse Politicians', 'In the past, a public notice stating "Do not talk about national affairs" (Xiutan guoshi) was posted in many teahouses.'[47] A drawing of Chengdu teahouses has the caption, 'Don't talk about national affairs but smoke freely', visual evidence of the existence of such a public notice. It is difficult to trace the origin of this public notice. In his novels about late Qing Chengdu, Li Jieren did not mention such a notice in his detailed accounts of teahouses. Yu Xi's article was published in 1943, when he regarded the notice as a relic of the 'past', meaning that at least in 1943 it was no longer common.

Another account from 1942, however, indicates that such posters were still publicly displayed although in the form of humorous couplets: 'If someone asks your opinion, do not talk about national affairs, just drink your tea' (Pangren ruowen qizhong yi, guoshi xiutan qie chichi).[48] In March 1945, when the war was almost over, Bai Yuhua wrote an article titled 'A Chat on "Do Not Talk about National Affairs"' about this phenomenon. According to the author, 'In the teahouses off the main roads of Chengdu and those in the market towns and settlements outside the city, a public notice "Do Not Talk about National Affairs" can often be seen.' He in fact suggested that such posters could still be found in some out-of-way teahouses in wartime Chengdu, which caused him to comment:

This is a backward, not progressive phenomenon. A strong democratic country should not have such a shortcoming, especially during a war that is crucial for the survival of the nation. People's involvement in national politics, the military, and the economy can give the greatest and most effective aid in the War of Resistance. A country's success in political, military, and economic affairs cannot be based simply on reading the outlines and principles of a few books. What can we not discuss? It should be all right as long as there is a limitation. Folks with conservative ideas should open their minds. Here, I hope that the local authorities can tolerate the following three topics: the war that is deciding the fate of the nation, current affairs, and the resistance movement. As long as we act under the government's leadership and guidance, what national affairs can we not talk about?[49]

The author thus expressed his dissatisfaction with governmental control although he was not overtly critical. Here, the author did not risk calling for true freedom of speech but simply asked for permission to discuss the war and its progress.

Posting such a public notice sparked criticism of Chengdu residents' lack of courage to speak out against authority. This blame seems unfair; notices could be found at teahouses in other regions as well. In Lao She's drama Teahouse (Chaguan), a similar public notice—motan guoshi—was also posted in teahouses in late-Qing and Republican-era Beijing. Although the wording differed slightly (xiutan, or motan, or wutan), these notices had the same meaning.[50] From a certain angle, a sign that read 'Do not talk about national affairs' itself was evidence of people's anger and desire to complain about the dictatorship under which they lived, which might serve a similar function as the message sent by those who tape their mouths shut in demonstrations for free speech.

Ultimately, the government could not suppress the topic of politics in wartime conversations. Patrons who frequently discussed politics in teahouses and whose opinions drew attention were humorously known as 'teahouse politicians' (chaguan zhengzhijia) in Chengdu. In his 1943 article, Yu Xi stated that after the war broke out, people talked about politics more than ever before. It seems that Yu was uncomfortable hearing political talk. 'National affairs', he wrote, 'do not concern us'. He claimed his attitude was not one of indifference but of exasperation with the stupidity of those who claimed to be 'concerned with the nation' and 'having a political mind' in their loud, daily arguments over politics in the teahouses. For example, those who often proclaimed that 'So-and-so is a great man' or 'So-and-so is covering up a conspiracy' irritated him. People who 'thought of themselves as having political insight' often deliberately and mysteriously revealed one or two pieces of 'important news', which they immediately emphasized would never be reported in the newspaper. His essay mocked ignorant 'teahouse politicians' who liked to show off by telling 'important news' and name-dropping.[51]

'Teahouse politicians' were usually those who read newspapers and liked to discuss politics. They lingered for hours each day in the teahouse, and what they heard became fodder for future discussions. They usually believed they were superior to those who did not understand politics and they always wanted to be the center of teahouse discussions. They spoke loudly and disliked opinions that differed from theirs. They wanted others to believe they were always right. Of course, some teahouse politicians earned a positive reputation while others became objects of ridicule. They behaved like actors on a stage and often gave their speeches in public. To a certain extent, they could influence public opinion. Although most public talk was not taken seriously, the teahouse did provide an informal forum in which people could express political views. The government, however, used force to put an end to any remarks it considered negative. In fact, talking about national affairs went on every day and in every teahouse; the notice 'Do not talk about national affairs' was more a means for teahouse managers to deal with the government than with patrons because through it they could avoid responsibility for conversations the government did not like.

This article reveals some interesting things 'between the lines'. The author disliked 'teahouse politicians' probably because he resented the government's treatment of patriotic people and because the authorities punished those who expressed unpopular ideas. So, from the author's point of view, 'teahouse politicians' were very stupid to get involved in politics, which the government never allowed. Or, the author probably was unhappy at the teahouse politicians' irresponsible claims, or resentful of their allegiance to a broader cause. Some elites thought that only they were qualified to talk about politics and became uncomfortable and even felt threatened when someone they considered inferior engaged in political talk. They did not want these people to be in the spotlight. In fact, although some political views seemed 'unprofessional' or 'silly', these discussions were the only outlet available to most people. Some people who talked about politics might know little about the subject, resulting in derision from others. Still, the teahouse was an important venue for making their voices heard, and certain factions always shared their opinions.

The End of an Era (1945-1950): Surviving the Civil War

After the War of Resistance, political talk again became taboo as the Civil War deepened and the pro-democracy and anti-despotism movement gained momentum. Most of the posters were replaced by the Nationalist party flag, the national flag, portraits of Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek, and the Citizens' Pledge. The Nationalists did not tolerate public criticism. In the late 1940s, as resentment grew against corruption in the Nationalist government, inflation, and social disorder, the teahouse became commoners' only outlet for their frustration. When people became angry and started shouting, the teahouse keeper would say, 'Be careful! The walls may have ears', meaning secret agents might be listening in.[52] The Nationalists suppressed the pro-democracy movement but on 27 December 1949, nearly three months after the establishment of the People's Republic of China, the People's Liberation Army captured Chengdu.[53]

Political turmoil not only had an impact on the teahouse trade but also created new teahouse politics. Soon after the war ended, three major authorities in Chengdu—the Chengdu Security Army, the Military Police, and the municipal government—issued a public notice that contained five rules:

1. People who served in the military or who were members of illegal organizations were strictly prohibited from gathering and holding any meeting in lodges or teahouses;

2. 'Unworthy people' (buxiao zhitu) were strictly prohibited from mingling with prostitutes or gambling;

3. 'Law breakers' (feifa fenzi) were strictly prohibited from gathering in the teahouse to drink settlement tea or disturb public order;

4. Anyone who damaged the property of lodges or teahouses had to reimburse the exact amount of the damage; and, 5. Anyone who violated any of these restrictions was to be severely punished.[54]

This public notice, like the many other regulations regarding the teahouse enacted during the late-Qing and Republican periods, reflected the government's two major concerns: political gatherings and public order. Regarding the former, the government tried to restrict the exercise of political rights, including by soldiers and Communists and their supporters, by prohibiting public activities that could develop into a political threat. Regarding the latter, the government was motivated by the need to maintain public security, but often also used ambiguous terms such as 'unworthy people' and 'law breakers' to attack political opponents rather than simply to maintain social order.

Although the government paid attention to the conversations held in teahouses, it scrutinized the public meetings held there even more carefully. The police and local government sent covert agents to spy on meetings of soldiers in an effort to learn about and squelch any rebellious action. As we have noted, the authorities also tried to control what people read and watched in the teahouse. Such supervision reached its zenith during the war, but the government also continued this tough policy after the war. In 1946, for example, the police sent a secret agent to the Sleeping Stream Tea Balcony to investigate a gathering of former military school classmates. The investigator reported that one Liang Qinghui organized the meeting to discuss how they could earn a living after being discharged from the military following their service on the frontlines. The group established an alumni association and elected Liang president to seek relief from the government and request that memorials be built in various places for their classmates who had been killed in the war.[55] That same year, the local government issued a public notice restricting such gatherings:

Under the order of the Sichuan Provincial Capital Police on 21 October 1946, because some soldiers recently organized gatherings without permission and held meetings in inns and teahouses, the Military Security Committee has ruled that such activities be restricted in an effort to cut social disorder off at its roots. The professional guilds must hereby notify all shopkeepers of inns and teahouses that they should immediately report any meetings of military people in their inn or teahouse to the Bureau of the Military Police. Otherwise, they will be punished harshly.[56]

Government officials not only enacted regulations to control gatherings of military personnel but also required professional guilds and their members to act as informants to report any meeting in a teahouse to the government. The available sources indicate that most of these meetings were social and did not have a political agenda. Still, the government sought to eliminate this potential threat. That the government overreacted is reflected in the crises it faced as the democracy movement gathered momentum after the Civil War broke out.

One excuse the government gave as it sought to control teahouses was to change so-called backward social customs in the name of the 'national emergency.' In 1948, the governor of Sichuan issued an order, called 'correcting the bad habits of gambling and idleness in the teahouse', claiming that it was 'time for mobilizing, controlling turmoil, and building the state', and 'for people to take responsibility and work hard'.[57] But 'bad habits' persisted, and the 'rise in gambling' and the 'prosperity of teahouses' continued unabated, which greatly affected people's peace of mind, sense of security, and the national economy. The governor also accused teahouses of being unhygienic and responsible for the spread of infectious diseases. Furthermore, because gossip, 'licentious songs' and 'evil plays' contributed to superstitious beliefs and immoral behavior, the governor supported teahouse reform for 'popular and social education', to 'turn uselessness into usefulness', to 'regulate people who do not follow rules', and to 'improve the city's appearance and sanitation'. Under this order, no new teahouses would be allowed to open, a move the governor believed was an 'important procedure for changing customs and habits', 'mobilizing people', 'controlling turmoil' and promoting 'state building', The governor wanted to ensure that officials took these issues very seriously as he carried out this radical new policy.[58]

In the meantime, the police of the Sichuan provincial capital issued regulations called Temporary Rules for Regulating Teahouses (Sichuan shenghui jingcha ju guanli chashe ye zanxing banfa), which were even more detailed.[59] Following these regulations, the Chengdu municipal government issued Restrictions of Teahouses in Chengdu (Chengdu shi chaguan ye qudi banfa), which added new limitations: No new teahouses were allowed to open; teahouses in locations that affected public sanitation or blocked traffic were to be removed or shut down; teahouses could not move to a different location unless this became necessary to accommodate a public project such as the widening of roads; any transfer of ownership would not be officially recognized; teahouses that had been closed for longer than three months would not be permitted to reopen and their licenses would be revoked; and violators of the regulations would be punished according to the extent of the violation.[60] These regulations enacted by the provincial authorities, the police, and the municipal government all sought to limit the number of teahouses and the services they offered, but the regulations put forth by the police were the most detailed and concrete and expressed the strongest political orientation. The regulations imposed from the late Qing to the late Republican period not only reflected the state's increasing control over teahouses but also the its need to constantly reassert its authority given that these regulations were often ignored.[61]

Conclusion

The teahouse was always a political arena where patrons were consciously or unconsciously drawn into the orbit of politics. Elites and local government officials always had a purpose when they criticized the teahouse and teahouse life. Sometimes it was to improve the city's image, and other times it was to promote cultural enlightenment, attack a 'backward' lifestyle, preserve social order and stability, or protect the interests of their own groups and political agendas. Some people regarded the teahouse as a negative influence on society, as a place full of vice, where people wasted time, gossiped, spread rumors, smuggled, and so on, but some considered the social and economic functions of the teahouse an indispensable part of everyday life. These different opinions also reflected attitudes toward popular culture. The elites who held the negative view usually supported government regulation and believed that restricting the teahouse business and teahouse life was necessary, while others—although they thought reform was necessary—believed that the teahouse, despite its various problems, was an important tradition in urban society and contributed to cultural and economic development.

The teahouse played an important role in politics, especially in an era when people received most of their information on current events there and used them as places for political activities. Politics infiltrated the teahouse through other means as well. In fact, it is clear that many people liked to discuss politics in the teahouse. Regardless of their ability to articulate their views, knowledge of current events, or political orientation, people involved in political discussions had an impact on others. 'Teahouse politicians' could at least make a voice heard that was different from the official one. Throughout the Republican period the government demanded that teahouse managers report conversations critical of the government and its policies. The public notice 'Do not talk about national affairs' that was posted in teahouses might also have been a kind of protest by serving as a proclamation that free speech was not allowed. To a great extent, the teahouse was a barometer of politics, where the topics of conversation and patrons' freedom to express themselves changed along with the political situation. Although most patrons tried to avoid punishment by not talking about sensitive issues, some people, especially leftists like Wen Yiduo, who called for speaking out in the teahouse, struggled to gain rights that the government tried to suppressed at all costs. Wen Yiduo paid the ultimate price when he was assassinated after giving a public speech in which he challenged the power of the Nationalist government.[62]

Teahouse culture, while tenacious, inevitably changed under the influence of local and national politics. On the one hand, throughout the four periods discussed, teahouse politics remained more or less the same, with people discussing various topics despite the risks, the government trying to enforce its regulations, authorities suppressing criticism and dissent, many kinds of disputes and conflicts taking place, and social groups and organizations using the space for their activities. But on the other hand, politics in the teahouse was different. From the late Qing to the early Republic, the government paid more attention to the reform of local operas and popular culture while people used the teahouse for political protests. During the New Cultural Movement of the late 1910s and early 1920s, conversations in teahouses focused on more cultural issues, such as one's identity, heritage, and the conflicts between new and old cultures or between Chinese and Western cultures. Teahouse politics reached its zenith during the war, when the teahouse became part of the state's propaganda machine. The government wanted to accomplish several goals through the teahouse: to mobilize people, inspire patriotic zeal, suppress activities that threatened authority, and enforce its absolute power. By using slogans and the Citizens' Pledge, the government wanted people in the teahouse to mobilize and participate in official movements, such as military service and raising money, and wanted to promote patriotism and the New Life Movement. One of the government's most important targets was so-called traitors, a term for those serving Japanese interests but one that eventually was used to anathematize anyone who challenged the government's power and authority. During the Civil War, any political gathering became taboo and any political talk became dangerous as the democratic movement gained momentum and the economy deteriorated.

Three kinds of politics were evident in the teahouse: Mass politics by ordinary people, elite politics by intellectuals and reformers, and state politics by the government. Thus, politics in the teahouse became very complex, multifaceted, and multileveled. The freedom of commoners to express their political views ultimately was suppressed by the cultural hegemony of the elite and by state power. Elite reformers tried to change the teahouse in order to expand their influence on public politics as the liaison between the people and the state. Sometimes they depended on state power to achieve their goal of teahouse reform, but other times they resented state control of this public forum. The government's role was also comprehensive; the state attacked and suppressed the expression of grass-roots political opinion, while it developed a flexible attitude toward elite politics, in which support or attack was determined by the government's interests. These three kinds of politics coexisted and interacted in the teahouse, making teahouse politics complicated and colorful.

Notes:

[1] There is a famous saying in China: 'When the empire is peaceful, Sichuan is the first to have a rebellion; when order is established in the empire, Sichuan is still in chaos' (Tianxia weiluan Shu xianluan, tianxia yizhi Shu weizhi). This saying emphasizes Sichuan's uniqueness and strategic position in national politics and also the difficulties in governing the province, which has been first among the provinces in population since the nineteenth century.

[2] See Di Wang, 2003: chap.2.

[3] On the development of urban administration in Chengdu, see Stapleton, 2000a; Di Wang, 1993: 401-2; Di Wang, 2003: chaps. 2, 4, 5; Qiao Zengxi, Li Canhua, and Bai Zhaoyu, 1983; He Yimin, 2002: chap. 3.

[4] Sichuan tongsheng jingcha zhangcheng, 1903; CSJJD, 93-2-2559 and 93-6-2718; GMGB, Dec. 16, Dec. 26, 1916; CSSN, 1927: 510-12; CDKB, Apr. 2, 1932; XXXW, Mar. 16, 1945; Jia Daquan and Chen Yishi, 1988: 369; CSSD, 104-1388 and 104-1406; CSZGD, 38-11-298; Sichuan sheng zhengfu shehuichu dang'an, vol. 186: 1431. The general regulations pertaining to all service occupations or informal policies that were implemented are not included. Therefore, one surmises teahouses suffered even more restrictions than those discussed here.

[5] Di Wang, 2003: chap. 7.

[6] For more detailed information of this period, see Stapleton, 2000a; and Di Wang, 2003: chaps. 4, 5.

[7] Qin Shao has discussed how reformist elites regarded the teahouses in Nantong as 'backward' establishments and tried very hard to reform them (Shao, 1998). I have also discussed how teahouses in Chengdu were a convenient target of urban reform (Di Wang, 2000; Di Wang, 2003: chap. 5).

[8] Sichuan tongsheng jingcha zhangcheng, 1903; Shengyuan jingqu zhangcheng, n.d.: 27, 30.

[9] Regarding the movement, see Di Wang, 2003: chap. 7. The leaders of the constitutional movement and the Railroad Protection Movement, including Pu Dianjun and Luo Lun, negotiated with Zhao Erfeng, acting governor-general, with the result that Pu was made governor. But, when Qing soldiers rioted and looted banks and other businesses in most of Chengdu's commercial districts in early December 1911, Pu and other major officials in the new government fled for their lives. The riots were soon quelled and Zhao Erfeng was killed by the allied forces of the New Army headed by Yin Changheng and the revolutionaries. Yin then became governor of the Sichuan Military Government (Sichuan jun zhengfu) established on December 10, 1911 (Wei Yingtao, 1981: chaps. 4, 5; Stapleton, 2000a: chaps. 3, 5; Di Wang, 2003: chaps. 5, 7).

[10] Di Wang, 2003: 228-30; Stapleton 2000a: chap. 7; Kapp, 1973: chaps. 1, 2.

[11] Li Jieren, 1980 [1937]: 788; Han, 1965: 228-29.

[12] TSRB, Aug. 6 1909; May 25, 1910; GMGB, June 14, 1912; Oct. 7, 1929.

[13] GMGB, May 5, July 29, 1917.

[14] Ibid., July 1, 1916; Aug. 20, 1917; Wu Yu, 1984, I: 265-66.

[15] Di Wang, 2003: 228-30; Stapleton, 2000a: chap. 7; Kapp, 1973: chaps. 1, 2.

[16] These five warlords were Liu Xiang, Liu Wenhui, Deng Xihou, Tian Songyao, and Yang Sen. Chengdu had five mayors during this period, all of whom were generals under these warlords. During this period, Sichuan was commonly regarded as one of the most unstable provinces but in fact, under this power structure, Chengdu was relatively peaceful, avoiding war as it did in 1917 (Kapp, 1973: chap. 3). At the end of 1932 war broke out between Liu Xiang and Liu Wenhui and another war broke out the next year between Deng Xihou and Liu Wenhui. Both wars were fought in the streets of Chengdu, resulting in many deaths and an enormous loss of property in the worst catastrophe since 1917. These warlords struggled to grab more financial resources by dramatically increasing taxes, smuggling opium, and controlling the economy. High taxes and economic instability, exacerbated by the presence of bandits, forced many landlords to sell their land and move to the city. Many ended up in Chengdu and became new customers of the teahouses there.

[17] Kapp, 1973: chaps. 3, 4, 5; Qiao Zengxi, Li Canhua, and Bai Zhaoyu, 1983: 15; Zhang Xuejun and Zhang Lihong, 1993: 296; He Yimin, 2002: 345-46.

[18] GMGB, Apr. 9, 1917.

[19] Ibid., Feb. 10, 1922.

[20] Lu Xun, 1973 [1921]: 359-416.

[21] On the regulation of teahouse theaters and performances, see Chapter 5.

[22] CDKB, Apr. 2, 1932; Jia Daquan and Chen Yishi, 1988: 369.

[23] In order to have more control, Chiang Kai-shek himself concurrently held the post of governor of Sichuan.

[24] In 1940 Chengdu suffered serious food shortages that resulted in rice riots. To address this problem, as well as the increasing number of Japanese air raids, the government ordered residents to evacuate. People lived in the shadow of war, and 'running for their lives whenever sirens sounded the alert' (pao jingbao) became a part of daily life from 1938 to 1941. People began moving back to the city in 1941 and 1942 after the Japanese shifted their focus to the Pacific War and stopped bombing. From October 1938 to August 1941, there were thirteen air raids. The worst attacks, on June 11, 1939, October 27, 1940, and July 27, 1941, killed and wounded several thousand people and made homeless countless more, and reduced many streets and districts to rubble (Liu Xiyuan, 1998: 148-51).

[25] For a time, the government tried to 'regulate wartime life' and generated a discussion that linked the 'national fate to tea drinking' (chicha yu guoyun) (XMBWK, Oct. 27, 1943). There is no study of wartime Chengdu but a few of wartime Chongqing. See McIsaac, 2000b; Zhang Jin, 2005.

[26] Zhou Wen, 1999: 229; XXXW, Apr. 9, 1938; Zhou Zhiying, 1943: 224. Teahouses and teahouse theaters took part in patriotic activities, especially fund-raising, from the early stages of the War of Resistance (CDKB, Aug. 25, Aug. 27, Sep. 1, 1938).

[27] HXWB, June 16, Nov. 23, 1941.

[28] Jian Fu, 1942; Qiu Chi, 1942; Zhou Zhiying, 1943: 246.

[29] Wang Qingyuan, 1944: 37-38; Zhou Zhiying, 1943: 224.

[30] CSZGD, 38-11-1103.

[31] This story described crimes of the Japanese invaders and called on fellow countrymen to organize for self-protection as all Chinese fought for their lives. The script claimed, 'We will fight for victory in recovering our motherland. We would rather die as a hero than live as a slave without a country' (CSZGD, 38-11-1103). Regarding Yue Fei in historical memory, see Huang Donglan, 2004.

[32] CSZGD, 38-11-1103.

[33] Ibid., 38-11-950, 38-11-951.

[34] The guild especially organized a committee called the Committee on Lecture Platforms (Jiangtai weiyuanhui), which had three to five members per district, for a total of nineteen people (CSSD, 104-1401).

[35] CSZGD, 38-11-952.

[36] Class A teahouses were required to display the GMD and national flags, and portraits of the founding father Sun Yat-sen, as well as the president and chairman of the national government (the chairman's portrait on the left and president's on the right). A blackboard, a lectern, magazines and newspapers, pictures, and slogans were also required. Class B and C teahouses had to have all of above items except the lectern. Those that did not meet the requirements by a certain deadline were to be fined, and those that refused to follow this order were to be shut down. The mayor also required the Teahouse Guild to report the names, locations, and owners of all teahouses in Chengdu (CSSD, 104-1384). The government enacted 'The Setting of Teahouses', which gave concrete instructions about décor based on a teahouse's economic capacity, size, and class. Class A teahouses had to post cartoons, slogans, charts, and pictures, had to provide books and newspapers for patrons to read, and had to have a blackboard for displaying propaganda and news. Class B teahouses had most of the same requirements, but pictures and books were optional and the blackboard was smaller. Class C teahouses had to display the cartoons, slogans, and charts, but not the pictures, and did not have to have newspapers or a blackboard (ibid., 104-1388).

[37] Ibid., 104-1390.

[38] Ibid., 104-1388.

[39] Here are some examples of the slogans. On transportation: 'Develop transportation for taking military supplies to the frontlines', 'Transportation in the rear areas is just like fighting on the frontlines', 'Transportation plays a key role in the War of Resistance' and 'Transportation depends on the power of humans and animals.' On air defense: 'No air defense, no national defense', 'Develop air defense', 'Building air defense is strengthening national defense' and 'Everyone contributes to buying aircraft for killing the enemy'. On economizing and saving: 'Practicing strict economy promotes saving', 'Economizing and saving establishes a foundation for our children', 'Savings bonds benefit us and the nation' and 'Economizing promotes the fight against the Japanese', The government also sought financial support and stressed the importance of raising money: 'It is natural that the rich should donate more money', 'To donate money for the military is to improve the morale of soldiers' and 'Respond enthusiastically to the call to donate rice and money' (ibid.).

[40] Ibid.

[41] Some praised the heroes of the War of Resistance and some, such as Stories of Bravery (Yingyong shiji) and Yue Fei, the heroes of ancient wars. Anti-Communist themes characterized some books, such as Disbanding the New Fourth Army and Strengthening Military Discipline (Jiesan Xinsijun yu zhengchi junji). Some were about traitors, such as Nets Above and Snares Below (Tianluo diwang) and This Is Wang Jingwei (Ruci de Wang Jingwei). Some promoted Nationalist Party ideology, such as A Popular Reading of the Three Principles of the People (Sanmin zhuyi dazhong duben) and A Brief Plan of National Construction (Jianguo fanglüe). Some addressed mobilization of the masses in the resistance movement, such as The President's Call for Sichuan Folk-followers (Zongcai gao Chuansheng tongbao shu) and Outline for Mobilizing the National Spirit and Its Implementation (Guomin jingshen zongdongyuan gangling ji shishi banfa). There were also some general-interest publications on social reform, such as Sichuan Geography (Sichuan dili) and A Collection of Stories about the New Life (Xin shenghuo gushi ji) (ibid.).

[42] Ibid., 104-1401.

[43] Ibid., 104-1388, 104-1401.

[44] Ju Ge, 1942.

[45] Propaganda in the teahouse became so important and common that someone wrote an article entitled 'The Theory and Practice of Teahouse Propaganda', which discusses the importance and functions of teahouses, the value of teahouse propaganda and its relation to the war, and the preparation of teahouse propaganda, as well as how to do teahouse propaganda (Bo Xing, 1941). The Nationalist government continued this strategy even after the war ended. In 1948, the Sichuan Provincial Government enacted Regulations on Teahouses in Sichuan, which still required teahouses to hang slogans and pictures of the New Life Movement and enact sanitation, air defense, and poison prevention measures. The government also called on teahouses to provide books and newspapers for customers (CSZGD, 38-11-298).

[46] Ibid. These regulations detailed requirements for hygiene, which has been discussed in Chapter 1.

[47] Yu Xi, 1943.

[48] Ci Jun, 1942.

[49] Bai Yuhua, 1945.

[50] Lao She, 1978: 78, 92, 113.

[51] Yu Xi, 1943.

[52] Zhang Zhenjian, 1999: 321-22.

[53] Qiao Zengxi, Li Canhua, and Bai Zhaoyu, 1983: 9-11; He Yimin, 2002: 347, 585-86; Kapp 1973: chap. 8; Li Wenfu, 1998. In early December 1949 thirty-five Communists were executed at Twelfth Bridge (Shi'er qiao) (Liao Junyi, 1998; Tang Tiyao, 1998).

[54] CSSD, 104-1397. The original document is not dated, but Mayor Chen Bingguang held the position in 1946-47 (He Yimin, 2002: 354), indicating that this public notice was issued during that time.

[55] CSJJD, 93-2-759. There is a similar case in CSJJD, 93-2-3101.

[56] CSSD, 104-1388.

[57] On gambling in the teahouse, see Suzuki, 1982: 534; Di Wang, 2003: chap. 6.

[58] CSJJD, 93-2-2559.

[59] Ibid.

[60] CSSD, 104-1388.

[61] Teahouse managers did not support most of the restrictions, but they definitely favored the policy of limiting the number of new teahouses. Their motivation was clear: They did not want the competition that new teahouses would bring. See Chapter 2.

[62] Communists often used teahouses for meetings and networking. It was said that they often met in the teahouses on Horse Walking Street, Green Stone Bridge, East City Corner Street (Dongchenggen jie), Warm Spring Road, the Smaller City Park, and Long Fluent Street. Ma Shitu wrote the drama Three Challenges in the Prosperous Tea Garden (Sanzhan Huayuan) about the struggles between the CCP and special agents of the GMD (Chen Maozhao, 1983: 192-93). According the keeper of the Sleeping Stream Teahouse, CCP members often held secret meetings there because secret agents did not pay much attention to a place that mainly attracted high school students. The teahouse keeper knew their identity but pretended to know nothing about their activities (Wang Shian and Zhu Zhiyan, 1989: 156).