|

||||||||||

|

FEATURESEmperor Kangxi's Southern Tours and the Qing Restoration of West LakeLiping Wang 汪利平 University of Minnesota

Liping Wang has worked extensively on the history of Hangzhou and West Lake (see, for example, 'Tourism and Spatial Change in Hangzhou, 1911-1927' in Features). She has kindly allowed us to preview her new work on West Lake during the early Qing era. This study is presented in three parts:

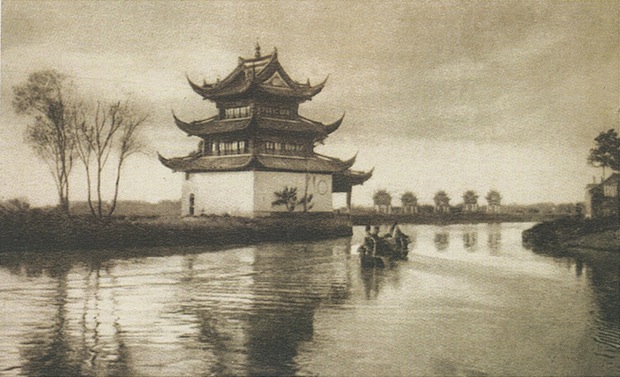

—The Editor In the autumn of 1649, You Tong 尤侗 (1618-1704) traveled from his hometown Suzhou to eastern Zhejiang. You had planned to bypass Hangzhou and go directly to the Qiantang River crossing to the south of the city. But while waiting for a ferry, he decided to backtrack several miles to Hangzhou. It was the great fame of West Lake that changed his mind. Growing up in the last decades of the Ming dynasty, You had heard much about the lake's beauty and promised himself to visit it one day.[1] He imagined that seeing the landscape would be like encountering a seductive woman, but this fantasy was shattered as soon as he got to the Lake, for he and his small party—the only visitors that day—came upon a miserable scene. The lake was chocking with silt, and weeds covered most of the water. The much praised willow trees that used to line the Su Embankment (Sudi 蘇堤) had been chopped down. You recorded: None of the countless branches and catkins were left. There were only broken roots jutting from the weeds. From a far I could see the dilapidated Lake Heart Pavilion (Huxing Ting 湖心亭)—it was all but collapsing into the water. The pavilions and towers around the lake were all in a state of ruination. In the past there were silk cables and ivory oars, fragrant carriages and precious horses, gentlemen with purple flutes, and beauties with red rouge. What have become of them now! All that confronted me were some lone crows flying past the setting sun, and a few lines of migrating wild swans crying sadly on the desolated marsh.[2] He immediately regretted having decided to visit the Lake: 'Instead of seeing it, far better to have [continued to enjoy it through] emotions in poetry, scenes in painting and the beauty of a dream!'[3]  Fig.1 The Grand Canal

This lament for West Lake is not to be mistaken for the typical melancholia expressed by former Ming loyalists when contemplating the ruins of the past. You was not interested in registering his feelings of loss or his rejection of the Qing political order; he was among the first group of Jiangnan 江南 [Lower Yangtze Valley] literati to cooperate with the new dynastic rulers, the Manchus.[4] Rather than nostalgia for the past, You was expressing his shock over the death of West Lake. The death was precipitous since only a decade earlier You Tong that heard people from his hometown bragging about visiting the famed landscape of the Lake. You Tong's disappointment and sadness over encountering a West Lake that seemed to have no future invites a number of questions: Why and how was this landscape destroyed? What is the relationship between the fate of West Lake and the realities of the Ming-Qing dynastic transition? On the other hand, people living in the twenty-first century know that West Lake survives to this day and that it remains the main attraction of Hangzhou. At what time was West Lake first revived after the fall of the Ming [for a discussion of Zhang Dai's dream memories of West Lake, see Duncan Campbell's translations in the Features section of this issue—Ed.], and what led to this rebirth? This article attempts to answer these questions by telling the story of West Lake's transformation from the late-seventeenth to the early eighteenth centuries. My analysis aims to show the complex and creative ways in which the Manchu Qing rulers manipulated the layers of historical memory and the aesthetic traditions surrounding the Lake. Looking into political and administrative developments in the early Qing period, I attempt to explain how new meanings were invested in and landmarks constructed at West Lake that had particular significance for the Qing rulers and their expanding empire. I argue that, in particular, the emperor Kangxi's tours and his patronage of West Lake were crucial factors in salvaging West Lake from extinction. Kangxi would elevate the Lake to become a key site in the Qing cultural landscape. West Lake, Literati Culture and Dynastic ChangeTo understand the changing fortunes of West Lake during the Qing, it is necessary to review its history. First of all, West Lake played an important role in the development of Hangzhou as city. The lake evolved from a lagoon at the mouth of the Qiantang River to become a freshwater lake in the Sui-Qing period. This was the time when Hangzhou became the southern terminal of the newly constructed Grand Canal (Dayun He 大運河). Hangzhou experienced it first period of growth thanks to this strategic position, but its proximity to the sea also meant the underground water was salty and not potable. In order to collect fresh water from the nearby hills, dikes were built on the Lake turning it into a reservoir. It now not only provided fresh water for the growing city, but was also a source used to relieve the surrounding farmland during times of drought. As a reservoir for Hangzhou the Lake became the focus for the city's officials. During the Tang dynasty, when the poet Bo Juyi 白居易 was a local prefect he repaired dikes and regulated the amount of water to be drawn from the Lake.[5] As a reservoir, West Lake required regular maintenance as well as periodical dredging to clean out silt and weeds. During the time of the kingdom of Wuyue 吳越 (907-978) of which Hangzhou was the capital , a dedicated body of a thousand solders was deployed to dredge the Lake. In the Song (960-1279), local officials continued to regard maintaining the Lake as of major importance. The most famous administrator of the Lake at the time was Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037-1101). During his second term as the Hangzhou prefect (1089-1091), Su found that West Lake had shrunken significantly due to increased silt and overgrown weeds. In a memorial to the court he explained the importance of the Lake to Hangzhou and was granted permission to fund a major dredging project. Su instructed the dredged up mud be used to build a causeway in the lake, and six bridges were built into the causeway to facilitate water flow. The causeway made it convenient for people to travel from the northern to the southern shores of the Lake. Moreover, by dividing the lake into two parts, it also added a new dimension to the landscape. Willow and peach trees were planted along the causeway, their extensive roots helping hold the soil together. The leaves and blossoms of the trees added beauty to the scenery. This causeway, named the Su Embankment after its creator would become a model of public irrigation works promoted by scholar-officials.[6] Bo Juyi and Su Shi did far more than protect West Lake's utilitarian function. Their own iconic status as writers in the culture of the literati was also crucial in enhancing the landscape where they worked. The importance of Su and Bo's contribution rested ultimately more on their reputation as paragons of literati culture than their work as energetic field administrators. If Su Shi the prefect physically saved West Lake, it was Su Shi the poet who elevated its landscape from the ranks of ordinary reservoirs and made it a unique site on the cultural map of imperial China. In the words of Ming-Qing literati, it was Su Shi's writing that 'made the landscape famous.'[7] Among the three hundred poems Su composed about Hangzhou many described his leisurely tours of the Lake. The most famous poem, which any educated person in the Ming-Qing would have been familiar with, makes an analogy between West Lake and Xishi 西施, the fifth century BCE beauty who was allegedly born in a village across the Qiantang River from Hangzhou. The poem reads: The shimmer of light on the water is the play of sunny skies, The blur of colour across the hills is richer still in rain. If you wish to compare the lake in the West to the Lady of the West, Lightly powdered or thickly smeared the fancy is just as apt.[8] From the Tang to the Song, countless people writers emulated Bo Juyi and Su Shi's poems when singing the praises of West Lake, and it became more famous with the repeated iterations. For people of You Tong's generation, the art and poetic conventions of the past had created a West Lake that was an aesthetic space combining poetry and painting with the physical landscape: The West Lake in poetry is one of 'shimmering under clear sky,' and 'mist-shrouded mountains in rain'; the West Lake in paintings is one of 'Oriels Singing in Waves of Willows', and 'Watching Fish at the Follower Bay'; the West Lake in dreams is one of 'Three months of cassia fragrance in the fall', and 'Ten miles of lotus flowers in the summer'.[9] However, West Lake had a negative dimension that was as significant as its fame in literati culture. During the Southern Song, the Lake became entangled in the indulgence and corruption of the court. The decision of the Song rulers to establish their capital at Hangzhou led to the city growing expansion into a metropolis of over one million people. A popular saying of the time held that Hangzhou relied upon 'firewood from the south and rice from the north, water from the west and vegetables from the east'. This is to say that water from West Lake was a necessity just as was fuel from the upper reaches of the Qiantang River, rice from the Lake Tai region, and vegetables from gardens in the city's eastern suburbs. The maintenance of West Lake was given unprecedented emphasize by the court. Dredges were regularly carried out to keep the size around thirty li 里 in circumference. The government also prohibited waste dumping in the Lake so as to prevent the water from being polluted. More importantly, the Lake which was situated right outside the city's western walls became the place for the imperial family and court officials to disport themselves. The water surface was littered with tour boats of various sizes and styles, and the lakeshores dotted with numerous villas and gardens. Critics soon connected the rolling hills and shimmering water of West Lake with the court's indulgence and its lack of interest in recovering the lost territories of the north occupied by the invading Jurchen Jin dynasty [for more on this, see 'Yue Fei and Qin Gui' in the Features section of this issue—Ed.]. Such criticism was encapsulated in a poem, penned on the wall of a hostel near the lake:

In the aftermath of the Mongolian conquest, the West Lake that had been regarded by Su Shi as being as charming as Xishi was now thought of having the same kind of seductive power of that great beauty-spy that toppled a dynasty.[10]  Fig.2 The temporary imperial residence, or detached palace (xinggong 行宫) on Solitary Hill island

The perceived connection between West Lake and dynastic decline was not merely something that related to its sullied reputation; in time it came to threaten the Lake's very existence. Not only did the gardens and villas of the Southern Song fall into disrepair and disappear following the dynasty's demise, but during the fourteenth century under the succeeding Mongolian dynasty of the Yuan the lake itself all but vanished. According to the mid-Ming local scholar Tian Rucheng田汝成, this was because the Yuan state had 'learned the lesson of the Song and gave up on the maintenance of the lake.'[11] Completely ignored by the authorities, West Lake fell victim to the forces that Keith Schoppa describes in his study of the history of Xiang Lake 湘湖 on the other side of the Qiantang River. That is to say, powerful local families reclaimed the land for agricultural purposes.[12] According to Tian, by the early Ming as much as ninety percent of West Lake had been converted into farmland. A large portion of the land was registered for taxes and thus its ownership was legalized. Tian Rucheng describes the condition of West Lake during the early Ming as follows: West of the Su Embankment the higher elevations became farmland while those lower down were turned into ponds. Patches of land were criss-crossed by roads like fish scales, and there was no room left. East of the embankment all that remained was a narrow waterway that flowed like a belt.[13] This means the western half of the Lake was completely reclaimed, and the eastern half had been reduced to a narrow strip of water. The gradual disappearance of West Lake continued for over two centuries. One of the reasons for this was that the contours of the coastal itself changed in the centuries after the Song. Hangzhou's underground water was no longer salty, and thus the city did not have to rely so heavily on West Lake for its drinking water. Nonetheless, the Lake's disappearance threatened the city's commerce because its many canals still needed its waters as a source. From the mid-Ming, several officials had attempted to restore the Lake, but they met strong resistance from local land-owners. It was only eventually restored in 1508 by a determined prefect by the name of Yang Mengying, who managed to convince the Ming court of its importance to the well being of Hangzhou.[14] It is said that Prefect Yang turned most of the reclaimed land back to water surface and more or less returned the Lake to the dimensions it had enjoyed under the Song.[15] But Yang's work concentrated only on the utilitarian functions of West Lake and it was not re-landscaped until over half a century later. During the late Ming, scholar-bureaucrats dominated the cultural world and they considered travel and sightseeing as an important part of their activities. In the 1590s, a local official was able to persuade the notorious eunuch Sun Long 孫隆, Superintendent of the Imperial Silk Manufactory of Suzhou and Hangzhou who was eager to win literati acceptance, to allocate funds to repair dikes, bridges and buildings in the lake-district. Sun's largesse resulted in newly paved passages, refurbished monasteries and the planting of new flowers and trees on the causeways. Once more West Lake once again became a charming landscape that attracted large number of sightseers. In this period of frantic cultural and material consumption, what Timothy Brook aptly calls the 'confusion of pleasure', sightseeing on West Lake was very popular among Jiangnan literati.[16] They not only enjoyed the scenery but they were also very interested in laying claim to this open recreational space through their literary compositions. One pervasive mode of representing the landscape was to see it as possessing feminine, seductive beauty; to tour the Lake was then a form of pleasure-seeking similar to a sexual encounter with a woman. Zhang Dai, a notorious dilettante of the late Ming (see more on Zhang Dai, see Features in this issue), epitomized such a view of the landscape when he wrote: West Lake… is a famous courtesan from the Singing Quarters, fair of both voice and visage. She leans against her doorway a meretricious smile playing across her lips. She is available to one and all, and as all may have their way with her, she is at once both the object of desire and the object of scorn.[17] When people in the early Qing reflected upon the tragic denouement of the Ming Dynasty at the hands of the Manchu-led conquerors, they often cited the indulgence of the literati in the pursuit of pleasure as being a key factor in the downfall. Having been a major playground for late-Ming literati, the future of West Lake again seemed precarious. Kangxi's Southern Tours and His Discovery of West LakeThe despoiled state of West Lake as witnessed by You Tong was not the result of direct warfare. When the Qing armies advanced on Hangzhou, the remaining Ming forces there to surrender to the conquerors thus sparing the city. However, the particular nature of the Qing conquest become a major factor in the immediate decline of West Lake: in particular, the Qing court underscored the strategic position of Hangzhou and, in 1647, one of the larger banner garrisons [qiying 旗營] was established in the city.[18] Banner officers chose for their headquarters the western part of the city closest to the Lake. They encircled a large tract of land and expelled tens of thousand of local residents. The Bannermen then used the Lake area as handy grazing land for their horses. They also chopped down the willow and peach trees three for firewood. The trees, though praised for their beauty, had been very important in retaining soil on the causeways and lakeshore. Without them the embankments quickly eroded.[19] All the while, local officials made little effort to save the Lake. Apart from lacking the resources to do so, their inaction was also to be rooted in their own ambivalence towards the Lake. The governor Zhao Shilin 趙世麟, for example, was enthusiastic and resourceful when it came to improving conditions in Hangzhou. Within the city he sponsored the dredging of canals to help facilitate transportation, and he also undertook the repair of the city wall. His efforts, however, stopped short of the Lake. In fact, he felt it was his duty to discourage sightseeing and pilgrimages in the West Lake area, seeing this as one way to restore social order and enhance the morality of the local people.[20] Ignored by local officials, West Lake once again became the target of land reclamation. Decades of encroachment significantly reduced the size of the Lake. Even the remaining area was becoming shallower and overgrown with weeds, as it had not been dredged since the 1600s. What saved West Lake from disappearing entirely was emperor Kangxi's (r.1662-1722) Southern Tours (nanxun 南巡). Kangxi undertook his first Tour of the South in 1684, visiting only Suzhou and Jiangning (Nanjing) in Jiangsu province. He did not venture further south to Zhejiang. He would make an additional five tours of the south, in 1689, 1699, 1703, 1705 and 1707, and he visited Hangzhou on each of these latter trips. During these visits the emperor gradually 'discovered' West Lake, and he developed particular ways of interpreting the cultural meaning of its landscape. In the scholarly work on Kangxi's Southern Tours to date particiular attention has focused on his inspection of hydraulic and irrigation projects and the state of local officialdom.[21] While existing studies focus on the ways the emperor saw Jiangnan, I would suggest that attention be paid to another dimension of the tours, namely, the ways in which Kangxi wanted to be seen through his forays into the core areas of Han culture. In light of the recent reevaluation of the nature of Qing imperial institutions, a fresh look at the Tours of the South from the angle of the monarch's practice of self-representation is of particular importance.[22] More than a mere quest for solutions to administrative problems, the Tours of the South should be considered as one of the more conspicuous and effective ways through which the Manchu emperor built his relationship with Han culture. The tours differed from the palaces in Beijing, where governance was handled routinely. They provided opportunities for Kangxi to engage in the politics of representation close to the home the Han elite's cultural sensibilities.  Fig.3 Lin Bu's 林逋 hermitage and the Pavilion for Free Storks (Fanghe Ting 放鹤亭) on Solitary Hill island

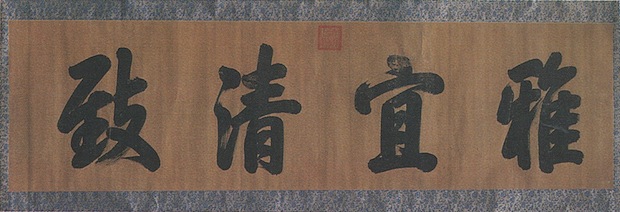

It is well-known that mastery of Confucian classics and Chinese literary skills takes years of study, and Kangxi had been cultivating these skills for over a decade prior to the first southern tour. Beginning in 1670, he put himself through a rigorous curriculum of Confucian classical study and appointed famous Confucian scholars such as Xiong Cifu 熊賜覆 and Li Guangdi 李光第 as his tutors. In addition to studying the classics through regular and ritualized lectures, Kangxi also recognized the importance of writing (prose and poetry composition, as well as calligraphy) in his quest to master Han culture. He made informal arrangements to study calligraphy and poetry. In 1671, he arranged for a calligrapher from Jiangnan to tutor him on the art.[23] In 1677, he ordered selected scholars who were 'erudite and expert in calligraphy' to act as his literary attendants.[24] The office that was staffed with these selected scholars became known as the Southern Study (Nan shufang 南書房). It was staffed by some of the most influential literati of the time, including the poets Wang Shizhen 王世貞, Zhu Yizun 朱彝尊, and the essayist Fang Bao 方苞. It is probably no coincidence that Kangxi's interest in Han literary skills caused him to develop a close relationship with Gao Shiqi 高士奇 (1644-1704), a man who hailed from Hangzhou. Gao was said to be skilled in essay composition, poetry, calligraphy and painting, as well as being a connoisseur of antiques. In the early years of the Kangxi reign, Gao arrived at Beijing seeking employment and ended up working as a scribe in the palace. His skills brought him to Kangxi's attention in 1672, and he was selected as one of the first two Southern Study tutor/secretaries. Quick-witted, Gao soon became Kangxi's favorite literary companion and he was instrumental in coaching the young emperor in literati aesthetics.[25] Kangxi once openly praised Gao for teaching him the skills of reading and composing poetry.[26] Gao accompanied Kangxi on his first three Tours of the South. It appears that the emperor went through a process in achieving a more nuanced understanding of Han literati culture and ways of appropriating it for his own purposes. As has been pointed out by Michael Chang in his study of Kangxi's tours, Han bureaucrats of late-imperial times came to see an emperor sequestered deep in the palace in Beijing as being the ideal form of sovereignty and they discouraged the monarch from venturing out of the capital. Imperial tours to Jiangnan were particularly apt to raise suspicion, because this area was best known for its luxury and sophisticated pleasures. During his first two tours, Kangxi showed much concern that his travels might be associated with negative historical precedents.[27] To prevent any possible criticisms that the tours were an imperial extravaganza, he was punctilious about limiting the size of the imperial entourage and the scale of local receptions. More importantly, during the first two tours Kangxi took measures to publicize himself as being a diligent ruler with no interest in leisure activities. Gao Shiqi appeared to be working in conjunction with the emperor on the creation of such an image. That is not to say that the emperor shunned sightseeing completely. Visiting the key sites and landscapes along the way was an important way for Kangxi to demonstrate his familiarity with high Han culture. In 1684, Kangxi toured several of the famous sites of Jiangnan, including Jingshan 金山 island in the Yangzi River near the city of Zhenjiang 鎮江, and Tiger Hill (Huqiu Shan 虎丘山) outside the great commercial city of Suzhou. However, he was careful not to let his sightseeing be seen as pleasure-seeking. In addressing his attendants and in his poetic compositions Kangxi reiterated that he was 'diligently seeking the hidden [suffering] of the people, and not here for the enjoyment of river and lake scenery'.[28] Kangxi's preoccupation with dissociating his tours from pleasure very much colored his first visit to Hangzhou. During the six days that he stayed there in 1689 much of his time was spent on what was to become standard imperial activities: pardoning criminals, rewarding laborers and soldiers who worked to transport the imperial entourage, inspecting the garrison force, and treating the local Bannermen to banquets and gifts. He did take one brief excursion to West Lake and visited several Buddhist monasteries in the area. However, he felt it necessary to explain immediately to the accompanying officials: 'We stopped by the Lake merely because it was located on the way to Yu's mausoleum. Some may think that we are enjoying sightseeing here; we are concerned about this.'[29]  Fig.4 The name of a temporary imperial residence, or detached palace (xinggong 行宫) in Hangzhou written in Qianlong's hand

Kangxi's concern was apparently heightened by a perception of West Lake as place of leisure and extravagance that was incongruent with the professed purpose of his Tour of the South. The emperor expressed his view of West Lake in a poem: West Lake was a place of painted boats and music in the past, my trip is to visit local places and inspect the mountains and waters. Never have I stopped my horse to enjoy food; I merely drank a cup of spring water at Hupao [monastery].[30] When local officials requested that the emperor extend his stay, Kangxi refused on the grounds that some might spread rumors about him being inclined to leisure.[31] On that first visit it was unclear to Kangxi what should be done about this famous, yet problematic, landscape. Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes to Part I[1] Jiang Liangfu, Xihu you ji 西湖游记, Hangzhou: Zhejiang Wenyi Chubanshe, 1985, p.149. [2] Ibid, pp.149-150. [3] Ibid, p.150. [4] In 1645, the very year that Jiangnan was conquered by the Manchus, You Tong took the civil service examination held by the new dynasty. In 1649, he had just passed an 'abbreviated exam' in Beijing thereby becaming eligible for official posts. [5] Zhou Feng 周峰, ed, Sui Tang ming jun Hangzhou 隋唐名郡杭州, Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1988, pp.90-92. [6] Zhou Feng, ed., Wuyue shoufu Hangzhou 吴越首府杭州, Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1988, pp.283-85. [7] Chen Renxi 陈仁锡, 'Xihu yueguan ji' 西湖月观记, in Ding Bing 丁丙, ed., Wulin zhanggu congbian 武林掌故丛编, Taipei: Tailian guofeng chubanshe, 1967, p.1. [8] Su Shi 苏轼, Su Shi shijii 苏轼诗集, Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1982, vol.2, p.430. [This translation is from A.C. Graham, Poems of the West Lake: Translations from the Chinese, p.23—Ed.]. [9] Jiang Liangfu, Xihu you ji, p.150. [10] Tian Rucheng 田汝成, Xihu youlan zhi 西湖游览志, Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1980, juan 1, p.2. [11] Ibid. [12] Keith Schoppa, Xiang Lake—Nine Hundred Years of Chinese Life. [13] Xihu youlan zhi, juan 1, p. 3. [14] Yang met very strong resistance from the land owning families, and eventually was demoted for 'restoring the lake and accomplishing nothing'. See Xihu youlan zhi, juan 1, p.3. [15] Ibid. [16] Timothy Brook, Confusions of Pleasure. [17] Zang Dai 张岱, Taoan mengyi, Xihu mengxun 陶庵梦忆,西湖梦寻, Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, 1984, p.174. For a detailed analysis of the late-Ming literati discourse of sightseeing on West Lake, see Liping Wang's 1997 dissertation, chapter 1. [For this translation from Duncan Campbell, see the Features section of this issue.—Ed.] [18] Zhang Dachang, Hangzhou baqi zhufangying zhilüe, juan 15, p.17b. [19] You Tong, Xitang quanji, juan 12, p.2; Wu Nongxiang 吴农祥, 'Xihu shuili kao' 西湖水利考, in Shi Diandong 施奠东, ed., Xihu zhi 西湖志, Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1995, juan 1, p.63; Wei Yuan 魏塬, Kangxi Qiantang xian zhi 康熙钱塘县志, 1719, juan 4, p.24a. [20] Zhao Shilin 赵世麟, 'Wulin cao' 武林草, fuke 附刻, in Wulin zhanggu congbian, pp.3-4. [21] Jonathan Spence, Ts'ao Yin and the K'ang-hsi Emperor has details of Kangxi's southern tours. For the mobility of the Kangxi court, see Spence, Emperor of China: Self-portrait of K'ang-his and Meng Zhaoxin, Kangxi dadi quan zhuan, pp.353-397. [22] For the recent discussion of Qing imperial institution and issues of Manchu identity, see Evelyn Rawski, The last Emperors; Crossley, A Translucent Mirror; and, Mark Elliott, The Manchu Way. [23] Meng Zhaoxing, Kangxi dadi quan zhuan, p.56. [24] Kangxi qiju zhu 康熙起居注, Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1984, juan 1, p.331. [25] Arthur Hummel, Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, vol.1, pp.413-14; Qingchao yeshi daguan, vol.1, p.79; Gao Shiqi, Qingyin tang ji, juan 9, 'dudan ji', p.1a; and, Deng Zhicheng, Qingshi jishi chubian, vol. 2, pp.803-804. [26] Gao Shiqi, Pengshan miji, 3a. [27] Michael Chang, A Court on Horse Back, chapter 1. [28] Da Qing Shengzu ren (Kangxi) huangdi shilu 大清圣祖仁(康熙)皇帝实录, Taipei: Xinwenfeng Chuban Gongsi, 1978, juan 5, p.224. Wang Zhimin 王志民, ed., Kangxi shici jizhu 康熙诗词集注, Huhhot: Neimonggul Renmin Chubanshe, 1994, p.265. [29] Kangxi qiju zhu, vol.3, p.1836. [30] Li Wei 李卫, Xihu zhi 西湖志, Hangzhou: Zhejiang Shuju, 1870, juan 5, p.20a. Hupao was a spring well at a monastery of the same name located near Hangzhou. [31] Kangxi qiju zhu, vol.2, p.1836. |