|

FEATURES

Perceptions of Change, Changes in Perception | China Heritage Quarterly

Perceptions of Change, Changes in Perception

West Lake as Contested Site/Sight in the Wake of the 1911 Revolution

Eugene Y. Wang 汪悅進

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Professor of Asian Art

Harvard University

Eugene Wang's study combines two themes pursued by China Heritage Quarterly in the second half of 2011: West Lake and the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. Wang's considerations of the Lake in the early, revolutionary years of the Republic of China resonate with the discussion of the same period by Liping Wang (also in Features in this issue), as well as Liping Wang's work on the Qing emperor Kangxi and West Lake. His journey through early modern representations of the Lake engages with Erwo Xuan, which Claire Roberts speaks about in her work on Chinese photography. Here too we are allowed a different, visual perspective on the Temple of Yue Fei, which overlaps with Zhou Zuoren's essay on the martyr-general and Qin Gui, translated by Tim Cronin (also in Features). And throughout we return, time and again, to the Ten Scenes, each era adding to the palimpsest of representation and memory that overlays the physical reality of West Lake.

This work originally appeared in the pages of Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, Vol.12, No.2 (Fall 2000), in an issue devoted to Visual Culture and Memory in Modern China edited by Julia F. Andrews and Xiaomei Chen. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author with minor stylistic changes, although the citation style and bibliography of the original print version have been retained. It is presented here in two parts:

Click here to download a PDF of the original article. For more downloadable PDF-format research papers by Professor Wang, click here.— The Editor

Photographer's Statement

Landslide, avalanche, and earthquake are among the metaphors often used to characterize a historical change, particularly a revolution. In the 1911 Republican Revolution, for instance, one sees 'tokens of the elements of volcanic eruption and confidently looks for seismic manifestations 10,000 miles away' (Dillon 1911: 874). The relevance of such rhetorical flights may in tact extend beyond mere figures of speech. Replacing imperial rule with a republican government, the 1911 Revolution not only dramatically changed the Chinese political landscape (Price 1990: 223-260; Schrecker 1991: 128-135), it also drastically transformed the physical landscape and people's perceptions of it. Two historical photo albums on the landscape of West Lake at Hangzhou 杭州, both published by the Shanghai Commercial Press, bear some eloquent testimony to this fact. One album, Views of West Lake,[1] appeared in 1910, one year before the overthrow of the Qing regime. The second album, West Lake, Hangchow, as part of a series titled Scenic China, first came out in 1915 (ZGMS). They were separated by the historical watershed year of 1911 in whose wake, it seems, nothing remained quite the same. It comes as no surprise that within such a short span, the Commercial Press was pressured by the changed political ethos not just to publish a new edition o n the same subject, but to come up with an entirely different album.[2] As a result, the two albums embody two historical epochs: the pre-Revolution and the post-Revolution, the imperial past and Republican present. Although we do not know who took the photographs that make up the 1910 album, we are certain that Huang Yanpei 黃炎培 (1878-1965), a famous revolutionary activist, was the creator of the 1915 album.[3]

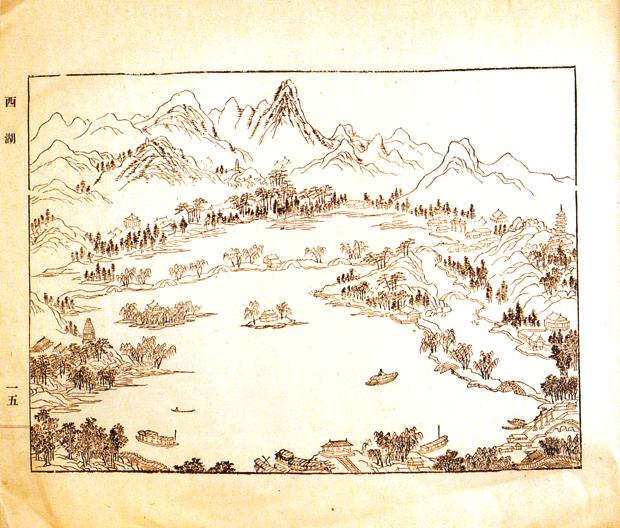

Fig.1 View of West Lake. 17th century. From MST: 15-16.

The preface Huang wrote for the album, dated 1914, articulates the program underlying the photographs:

I once visited West Lake with a group of seven or eight peers in 1906. Westayed at the Tower of Reading on the Solitary Hill for seven days. Since then, I have surveyed Mt. Lu in Jiangxi, Yellow Mountain of Anhui, and cruised down the Xin'an River to the east, only now returning to Hangzhou. It has been eight years, and what a change of landscape and things! Looking a round at the lake shores, one sees the Public Park, the Library, the Memorial Hall for Soldiers Who Died in Nanjing, the Shrine for Martyr Tao, the Tomb of the Three Martyrs (Xu, Chen, Ma) and the Shrine for Lady Qiu of Jianhu 鑑湖. These imposing new edifices, with their lofty stelae and painted posts and ridgepoles, have an infinite variety of sublime aura. As for the notable Qing officials' temples and shrines with their poetic inscriptions, even some isolated ink traces and fragmented silk pieces, are hard to find, if one were to look for them. I revisited the Tower of Reading and saw there rain-soaked window panes and dust-gathering couplet-displaying pillars. The building has languished beyond recognition. Contemplating the old traces and imagining the future, [one realizes that] while people and things come and go generation after generation, the lake and mountains remain intact. I have therefore taken these photographs, and hereby advise our readers: this West Lake is that of May of the Third Year of Republic of China! Noted by Huang Yanpei (ZGMS: 1: n.p.).

Huang's text no doubt explicates his landscape photographs, which might otherwise appear neutral in meaning. It is explicit about the author's political allegiance to the Republican revolution, which is expressed through a rhetorical opposition between the Republican present and the Qing past. Yet, there is also a conspicuous and dramatic shift in tone and mood in the text. Huang enthusiastically hails the new Republican memorials and triumphantly declares the landscape as belonging to the new era. What seems equivocal, however, is his attitude toward the 'old traces' of Qing officers' temples: 'their poetic inscriptions, even some isolated ink traces and fragmented silk pieces, are hard to find.' Is Huang here reveling in the increasing irrelevance of these old traces or is h e lamenting their passing into obscurity? For a person who had narrowly escaped a death sentence issued by the Qing authorities, Huang's anti-Qing sentiment is not to be

questioned. Yet, for a moment at least, Huang lapses into a pensive mood or a brooding reverie: ' Contemplating the old traces, and imagining the future, [one realizes that] while people and things come and go generation after generation, the lake and mountains remain intact.' The pensiveness is reminiscent of a traditional literatus-which Huang was, albeit with revolutionary leanings-sighing nostalgically over the change of landscape and historical circumstances in a philosophical vein. For a moment the seems to catapult himself from the plane of worldly affairs to a more transcendent plateau. This makes his final gushing outburst about the landscape being 'that of May of the Third Year of Republic of China' somewhat abrupt: a brassy blare that breaks the nostalgic reverie.

This elusive and subtle mood shift in Huang's text suggests a potentially problematic relationship between his stated purpose and the pictures. Just as are the photographs themselves, the verbal statement is elusive; it in no way offers a key to unlock the meaning of the pictures. Furthermore, it is difficult to map the textual mood shift onto the formal properties of the pictures, which work out mood changes in their own ways. This lack of correspondence between the two media poses a problem for us: how do we translate the author's written statement into his pictures or see his photographs as visualization of his verbalized intent? If our ultimate interest in Huang's photographs rests in their potential as visual testimony to the contemporary perception of the monumental change in landscape (in both its metaphoric and literal senses) brought about by the 1911 Revolution, such a visual testimony is anything but straightforward. It requires some corroborating testimony to be useful. A proper sense of the contemporary perception should not be derived from Huang's photograph album alone. The album is at once collective and partial in character: collective in that it is a valuable historical visual document that registers a way of seeing, a 'period eye' of sorts, different from our present perception;[4] partial in that it represents the vision of one particular revolutionary activist of the period. We might well wonder: to what extent did Huang's contemporaries share his photographic vision? How would Huang's contemporary viewers respond to his photographs, or to the landscape that he photographed? And, to return to our earlier concerns about the complexity of Huang's photographic vision, where might we find documents to support Huang's own testimony, and how do we characterize the latter in the first place?

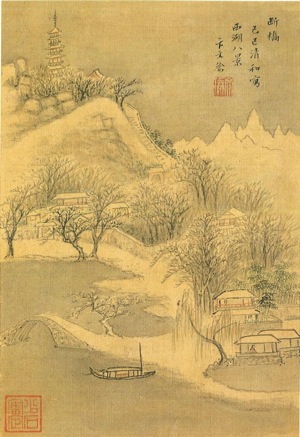

Fig.2 View of West Lake. 18th century. From XZ: 3.2-3.

Soon after Huang took his photographs, some travelers followed his footsteps. They stepped into the very spots that Huang photographed; they looked upon the vistas Huang framed with his camera lens. They subsequently wrote travelogues in which they reflected on what they had seen. Here is the testimony we need. In the following, I measure some of Huang's photographs against the observations made by four visitors, who came from a variety of social backgrounds. Where the photographs and travelogues agree, we have a shared period perception. Where they differ, we must either recognize undercurrents unarticulated or unacknowledged by the photographs or discern the gap between different social groups. In short, the analysis leads us to appreciate the dynamics and structure of landscape perception in the wake of the Republican Revolution. We learn to what extent the revolution changed both the landscape and the eyes set on it, and gauge its impact on perceptual habits.

The Photographer's Revolutionary Career

Huang Yanpei was a native of Chuansha 川沙, close to modern Shanghai. He earned his xiucai degree at age twenty-two. In 1901, when he was twenty-four, he passed the entrance examination and enrolled in the Nanyang Public School 南洋公學, which emphasized new and Western learning. Here he studied under, a mong others, Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培, an advocate of reform and the revolutionary cause who would later become Minister of Education for the Republican government and president of Beijing University. The radicalism of the faculty and students of the school attracted the attention of the Qing authorities, who discharged them en masse in 1902. Thereupon Huang returned to his native place, Chuansha. Sponsored by a liberal-minded timber merchant, Huang founded the new-style Chuansha Primary School and became its first president. In June 1903, Huang was invited to speak at a public rally in Nanhui 南匯 County, where he lashed out against the inept Qing regime that had dragged the country to the brink of catastrophe. He was arrested for his incendiary speech and given a death sentence, but a discrepancy between the central and local government decisions gave him a grace period. With the help of some friends and some American missionaries, he was released on parole, after which he fled to Japan. The following year, because of straitened circumstances in exile, he was forced to return to Shanghai, where he took up teaching and founded a few schools.

In the meantime, his revolutionary zeal went unabated. In 1905, he joined the Revolutionary Alliance, and the year after, he succeeded Cai Yuanpei as the secretary of the Shanghai branch of the Alliance. During the 1911 Revolution, Huang took a n active role in persuading Qing officials to defect. After the overthrow of the Manchu regime, he was appointed head of the Department of Education in the new provincial government of Jiangsu. Because the Republican government fell into the hands of Yuan Shikai 袁世凱, whose dictatorship and imperial aspirations jeopardized the revolutionary cause, some southern provinces, including Jiangsu, attempted the Second Revolution. In September 1913, a northern army led by the warlord Zhang Xun 張勛 sacked Nanjing. Huang resigned from his post in February 1914. Sponsored by the Commercial Press of Shanghai and the progressive newspaper Shenbao,[5] he embarked, with a modest entourage, on a tour that was to cover three provinces and eleven cities. In addition to inspecting the state of education in various cities, Huang was able to tour famous landscape sites such as Mt. Huang, Mt. Lu, and West Lake (Xu 1985: 1-19; Wang Huabin 1992: 1-82). He took numerous photographs, which were published by the Shanghai Commercial Press in a twenty-one-volume series under the title Scenic China (Wang 1992: 76-82). West Lake was the fourth of the series.

Four Tourists

Fig.3 Map of West Lake.

Fig.4 Remaining Snow at the Dividing Bridge. 18th century. From XZ: 3.34-35.

Built in 1909, the rail road between Shanghai and Hangzhou dramatically expedited the trip to West Lake (Zhou 1992: 249-251; XXZ: 4b). The train ride took only four hours[6] and helped stir a booming tourist industry around West Lake (XXZ: 1: 2-3). Long lured by the fame of West Lake as perpetuated over the centuries by a massive body of poetry, travelogues, and pictures, tourists, particularly those from Jiangsu and Shanghai, took advantage of the newly established transportation system and flocked to the lake.

For many, the excursion to West Lake was more than mere tourism: the sites on the lake had become a set of cultural topoi. loaded with the historical memory created by writings by generations of visitors. Touring West Lake was an experience of encountering or recalling the literary lore and historical legacy associated with these sites.[7] Tourists who experienced this culturally charged landscape engaged with and contributed to a discursive tradition in the form of poems and travelogues.[8] Four visitors' travelogues are examined here. The varying backgrounds of these visitors give us needed diversity.

The two Suzhou visitors, Gao Xie 高燮 (1878-1958) and Gu Wujiu 顧無咎 (d. 1929), were no ordinary tourists. They were members of the Southern Society (Nanshe 南社), a highly prominent and influential literary association, the largest one in early twentieth-century China, which played a key role in propagating revolutionary ideology. Its inauguration took place, in 1909 in a temple dedicated to a seventeenth-century anti-Qing martyr. Fourteen out of the seventeen who attended the inauguration were members of the Revolutionary Alliance (Yang/Wang 1995: 139-140). The association eventually drew a membership of 1100 and dominated the editorial pages of the liberal press to such an extent that it led to the popular expression: 'today's China is the world of the Southern Society' (Yang Yi 1997: 1: 44-47).

The members of the Southern Society were mostly scholars of gentry class. They followed the traditional literati custom of gathering to drink and exchange poetry as well as to tour famous lakes and mountains. It was one of these group trips that brought both Gao Xie and Gu Wujiu to West Lake. Well versed in classical literature, these gentleman scholars were given to articulating their contemporary concerns and sentiments through analogies with historical precedents, particularly the affairs of the Southern Song and late Ming, both of which were ended by foreign invasions. Much of this disposition is evident in the writing of the two Southern Society members, in particular Gao Xie, who was among the most active members of the society. As early as 1903, he was hailing the 'waking lion' from its slumber to confront the ' packs of tigers [and]…wolves' (Yang/Wang 1995: 8).

Little is known about the two Shanghai visitors except what we can glean from their own travelogues, published in 1920. Chen Yilan 陳儀蘭, a woman from Shanghai and an avid reader of travelogues, had long wished to visit famous landscapes. The old practice of keeping women homebound had confined her to the 'cosmetic bower' (zhuangge 妝閣), where she could only 'visualize in her mind the grandeur of mountains and magnitude of rivers and seas.' As a result of the 'dramatic change of the world' effected by the 1911 Revolution, she was able to venture outside the home to 'seek education in the four quarters' and finally got the chance to satisfy her craving to ' roam the famous mountains and rivers.' She traveled with her uncle, her sister, and her brother. The trip appears to have been well organized. The uncle was elected to be the group leader, and the brother its accountant; Yilan herself was its secretary. She initially thought her appointment to have been superfluous, because so much had already been written about West Lake. She was told that previous travel writers had put too high a premium on their tours and itinerary at the expense of the historical record. She could remedy the historical deficiency by 'narrating the dynastic rise and fall by way of noting the 'transformation of mulberry fields into seas: and registering changes in the world by following the transformation of localities' (XYH: 24: 1).

Fang Shaozhu 方紹翥, the other Shanghai native, was an eighteen-year-old high school student. In his childhood, he had heard people talking about West Lake. Like Chen Yilan, he had long yearned for a trip there and was often given to 'mentally conjuring up many an exquisite landscape scene, which filled [his] dreams time and again.' Finally, in 1917, he was able to join his schoolmates on a trip to West Lake (XYH: 25: 1).

The Fading of the Ten Views of West Lake

Fig.5 Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow. 18th century. From XZ: 3.32.

The landscape of West Lake that Huang photographed in the 1910s still bore indelible marks of the Qing dynasty. One of the Qing legacies was the reinforcement of the division of West Lake into Ten Views. The scheme goes back to the thirteenth century. By the fourteenth century, when the lake area suffered from lack of maintenance, the sites associated with these views became obscure and defunct. When the Qing first took over Zhejiang, West Lake h a d lapsed into serious disrepair and was heavily clogged by silt and mud. Repeated decrees from the Qing court between 1654 and the late eighteenth century led to its revival. The Qianlong emperor's Southern Inspections in particular spurred the renovation of 'ancient sites' (guji 古蹟) along the lake. A comparison between a seventeenth-century Ming topographic map [Fig.1] and that of an eighteenth-century Qing print [Fig.2] testifies to this point. Following a conventional topographic representation that goes back to the Southern Song, the seventeenth-century map takes the panoramic view of the lake from the east (i.e., the point of view of the city).[9] It shows little interest in highlighting the Ten Views: absent from the map is the famous view of the Three Stupas Reflecting the Moon. In contrast, the eighteenth-century map not only restores the missing Three Stupas—thereby registering the corresponding physical restoration of the site—but also carefully labels each of the sites associated with the Ten Views. Furthermore, it rotates the map's spatial orientation to favor the north side, where the Imperial Itinerary Palace was located (the emperor had to face south, commanding the Ten Views).

The Qing imperial claim to the Ten Views is more than cartographic fiction. During their visits to the sites, the Qing emperors Kangxi and Qianlong calligraphically transcribed the names of the Ten Views. Their autographs were then carved onto stelae and enshrined in pavilions that became the landmark s of the Ten Views. In other words, the Ten Views came to be closely associated with the Qing Emperor s' visits and their enduring legacy.

The 1910 photo album clearly favors these Ten Views. The album consists of forty pictures, with the Ten Views leading the way.[10] Particularly revealing is its representation of the two vistas of the south shore of West Lake. One view, known as Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow, centers on a ruinous pagoda standing on the hilly promontory known as Leifeng,[11] literally, Thunder Peak, an extension of the South Screen Mountain that lies to its south [Figs.1-3] (Qian 1983-198 6: 873-874; Tian 1980:

33; Chen 1977: 40-44). The pagoda had long been associated with the nearby Jingci 淨慈 Monastery, whose reverberating bells led to the naming of another famous vista, the Evening Bell at Nanping Range (Nanping wanzhong 南屏晚鐘). Both vistas are in fact associated with the same site.

Fig.6 Evening Bell at Nanping; or a Pavilion at the Nanping Range. Before 1910. From XHFJ: 7.

Fig.7 A Sunset View of the Thunder Peak Pagoda. From XHFJ: 9.

Since the Qing emperors' reinstatement of the Ten Views, their pictorial or topographic representation emphasized the emperors' stela pavilions. Instead of identifying a famous view, the stela pavilions themselves increasingly came to be the focus of the views and dominated subsequent visual representations. In one extreme case, a stela pavilion is mounted on the very center of the famous Dividing Bridge [Fig.4] (XHZ: 3: 2-3, 32-35). A similar visual scheme underlies traditional representations of the two views associated with the Jingci Monastery. In the eighteenth-century Gazetteer of West Lake (Xihu zhi 西湖志), the wood-block illustration of the 'Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow' (Leifeng xizhao 雷峰夕照) clearly gives visual prominence to the stele pavilion, next to which is the inscription 'Pavilion of His Majesty's Autograph' (Yubei Ting 禦碑亭).[Fig.5] The photograph 'A Pavilion on the Nanping Range' [Fig.6] in the 1910 album is striking in its compositional similarity to the eighteenth century woodblock print. Both compositions place the imperial stela pavilion in the foreground, unblocked by trees, whereas the pagoda is pushed to the background, peeping out from behind treetops. 'A Sunset View of the Thunder Peak Pagoda', in the same album, predictably follows the same visual scheme, which positions the imperial stele pavilion in the center with the pagoda to the left.[Fig.7]

Huang's arrangement of the two views is radically different. In representing the 'Evening Bell at Nanping Range,' he frames the view from inside the monastery, thereby including the pagoda and excluding the Qing stele pavilion from the composition.[Fig.8] His composition' A Sunset View of the Thunder Peak Pagoda ' takes in the vista of the pagoda a cross the lake.[Fig.9] The ' long shot ' makes room for the reflection of the pagoda on the lake surface, which is in effect more faithful to the original conception of the view that turns on the hazy effect of 'evening glow ' (xizhao 夕照); it also negates the Qing-period sleight of hand giving prominence to the imperial stele pavilion.

Fig.8 Huang Yanpei. Tzing Tze [Jingci] Monastery. 1914. From ZMX: 2:5.

Fig.9 Huang Yanpei. A Sunset View of the 'Thunder Peak' Pagoda. 1914. From ZMX: 2:19.

Huang's devaluing of the Ten Views is also revealed in his table of contents , which strips the Ten Views of their privileged lead status and intersperses them among other scenes. Moreover, several sites that could be named as part of the Ten Views are denied such a recognition. In his version of the Evening Bell at Nanping, [Fig.8] for instance, he gives the title 'Tsing Tze [Jing ci] Monastery,' and acknowledges its connection with the Ten Views only in the caption below the photograph: 'Located at the foot of the Huiri Hill 彗日峰, the monastery was built by Qian Hongchu 錢弘俶, Prince of Wu-Yue 吳越. Outside is the Pond of Mr. Ge. A pavilion houses a stele on which is inscribed 'Evening Bell at Nanping.' The monastery is majestic' (ZGMS: 2: 5). Note that it is the monastery that is 'majestic' and not the sight of the pavilion. The view of the Dividing Bridge is traditionally known as Lingering Snow at the Dividing Bridge (Duanqiao canxue 斷橋殘雪). Huang gives it a simple title 'The 'Broken-Off' Bridge.'[12]

Fig.10 Huang Yanpei. Watching Fish at the Flower Lagoon; Imperial Tablet at the Flowery Lagoon. From

ZMX: 2:20.

The increasing irrelevance of the traditional Ten Views in the 1910s is confirmed by our tourists' travelogues. In contrast to traditional tourists to West Lake,[13] none of our tourists organized their itineraries around the Ten Views, which may have stemmed from the physical change of the landscape around the lake. The sites associated with the Ten Views had received little maintenance or care since 1800. The spots that drew visitors were either those connected with famous historical figures and legends or villas and memorials associated with more recent personages or events. This does not mean that the Ten Views were forgotten, however; our visitors made passing notice of them. For Fang Shaozhu, the Shanghai high schooler, much of his impression of the landscape was programmed by the circulated West Lake lore that he had learned as a child. The Ten Views were an important component of the lore, so it is not surprising that he made an effort to track some of them down. This interest took him to the famous site of the Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow. Climbing to the top of the Leifeng Hill, he saw the famed pagoda 'standing in isolation':

So, this is what they call the Leifeng Pagoda! Underneath it, all the walls and fences are a bout to crumble. The broken tiles and fragmented bricks are everywhere, making it hard to tread through. The thistles and thorns of the undergrowth keep hooking our clothes. Disappointed, we all leave. (XYH: 25: 2)

Next, he tried the site of Watching Fish at the Flower Lagoon (Huagang guan yu 花港觀魚). What greeted his eyes were 'ruins, with one broken stele standing amidst brambles and rampant grass. The so-called Flower Lagoon was mostly littered lotuses and withering leaves floating on the water surface…. The few fish can hardly please the eye' (XYH: 25: 2). Fang's description explains the rationale behind Huang's photographic composition of the site, which focused on the stele pavilion.[Fig.10] This choice seems to contradict Huang's anti-Qing stance and his consistent devaluing of the Qing imperial stele pavilions associated with the Ten Views. In light of Fang's travelogue, it is apparent that Huang' s composition resulted from lack of alternatives. The dilapidated site had nothing to offer except the lonely stele pavilion, which could still evoke its former splendor as one of the Ten Views. In this regard, concern for the picturesque and the photogenic may just as well explain Huang's decision to position his camera away from the Leifeng Pagoda,[Fig.9] regardless of his political motivation.

Beyond the Picturesque

Fig.11 Huang Yanpei. (1) The Lake View from outside the Yung Chin [Yongjin] Gate; (2) Boat Landing outside the Yung Chin [Yongjin] Gate. 1914. From ZMX: 1:1.

The lake , after all, had a neutralizing and calming effect. No matter what political agenda Huang and his contemporaries may have found pressing, the vast expanse of the lake and the surrounding mountains may have made the tourists forget the political situation of the time—Yuan Shikai's jeopardizing of the Republican Revolution. Huang's picturesque landscape photographs do not seem to register the political agitation of the time. What lay behind a photographic conception of landscape was the unshaken conviction that it should resemble a painting. The tranquility that reigns in traditional Chinese landscape painting inevitably informed the early Chinese photographic imagination.

Fig.12 Bian Wenyu. Dividing Bridge. Album leaf. Ink and color on silk. Dated 1629. Private Collection. From Sotheby's Important Classical Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy. Hong Kong, May 1 , 2000. p. 16, Fig. 6.

Huang' s photo album begins with two compositions: one of the lake viewed from the Yongjin Gate 涌金門 on the west side of the city of Hangzhou and the other of a boat landing outside the Yongjin Gate.[Fig.11] In the larger of the two compositions, the canopied boat, suggesting the traditional activity of touring the lake, occupies the center with the Dividing Bridge to the far left and North Hill, dominated by the Baoshu Pagoda 保叔塔, as backdrop. The composition is reminiscent of the generic composition exemplified by an album leaf from the seventeenth-century painter Bian Wenyu 卞文瑜.[Fig.12] In Huang's photograph, three people occupy the canopied boat: the oarsman in the front, the steersman at the rear, and the tourist-passenger in long robe in the middle. The passenger performs the role of the traditional gentleman scholar cruising the lake. In a traditional painting, a lone figure manning a boat might evoke the placid life of a solitary fisherman or a scholar retiring to a rural home. The boat is central to a number of Huang's photographs of the lake (ZGMS: 1: 9, 11, 18, 26, 29). Wherever applicable, Huang' s captions remind the reader either that a certain poetic allusion 'fittingly describes the view in the picture' [Fig.13] or that the scene 'resembles a painting ' (ZGMS: 1: 9, 10). Such compositions convey a peaceful and leisurely mood, implying that when it comes to boating on a lake, nothing seems to have changed. These pictures, however, do not tell all the stories of what actually happened when scholars of the 1910s went boating on West Lake.

Part of Huang's photographic scenario was enacted by our visitors. Exactly one year after Huang took the photographs, Gao Xie, the Suzhou scholar, visited West Lake with other fellows of the Southern Society. In many ways, he played out what Huang's photography had inadvertently scripted for him. He 'called up a boat' to cruise on the lake (XYH: 23: 1). During the tour, many photographs were taken. It was at the scenic spot of Mirror Lake and Harvest Moon, however, that he began to reflect on these photographs:

Recalling the photographs taken on this trip, I give them respectively a title. The activity of our Southern Society in Shanghai can be called ' Picture of an Elegant Gathering at the Yu Garden' (Yuyuan yaji tu 愚園雅集圖); for the one taken when we first arrived at Hangzhou, it is 'Picture of Touring Wulin in Company' (Wulin tongyou tu 武林同遊圖); for the banquet held at the Apricot Flower Village, it is 'Picture of Drunkards at West Coolness' (Xiling fuzui tu 西泠膚醉圖); for the improvised meeting at the Seal-Carving Society, it is 'Picture of Elegant Gathering at Bright Lake' (Minghu yaji tu 明湖雅集圖); and the one taken here is ' Picture of Boating near the Three Stupas' (Santan fanzhou tu 三潭泛舟圖). (XYH: 23: 8)

Huang's photographs of boating on the lake may fit Gao' s purpose. It appears that for both Gao and Huang, what makes a photographic scene is interchangeable with what makes a pictorial scene. Huang's photographs therefore played rig ht into t his kind of cultural expectation.

Fig.13 Huang Yanpei. Bai's Causeway. 1914. From ZMX: 1:9.

Gao' s naming of his own photographs may confirm the impression stated earlier that for the educated and gentry classes in the 1910s, traditional formulations continued to shape their experience of landscape, their lifestyle, and their social activities. But the tranquility conveyed in Huang's photographs and Gao's naming is quite deceptive. The historical reality surrounding 1915 was in fact quite grim and disturbing. The meeting Gao named as the 'Elegant Gathering at the Yu Garden' in Shanghai took place on May 9, 1915. It was an unusual day: Japan had joined the Allied cause and was attempting to take over German-controlled territory in Shandong. In January 1915, Japan presented the Beijing government under Yuan Shikai with the notorious Twenty-One Demands, which included more territorial predominance, intervention in state and civic administration, and other aggressive requests. On May 9, the Yuan Shikai government accepted the Japanese 'ultimatum' regarding the Twenty-One Demands, which caused a national outcry. It was on this same day that the 'Elegant Gathering' of forty-two Southern Society members took place at the Yu Garden in Shanghai. Bemoaning their military impotence, these scholars were consumed by self-loathing and frustration and regarded themselves as 'good for nothing... unarmed bookworms.' All they could do was to gather and get drunk, and 'tour with nostalgia the fragmented land... the lakes and mountains bathed in the setting sun' (Yang/Wang 1995: 388). The next day, they set out for West Lake. The travelers included two of our visitors, Gao Xie and Gu Wujiu.

During their tour, the Southern Society members gathered at the Apricot Flower Village on the lakeshore to drink. Gao Xie recalls:

Liu Yazi 柳亞子 [1887-1958]... downed quite a few cups of wine in a row and was in a bold and uninhibited mood. Mr. Lin had too much and started to dance. Tea cups and bowls flew in the air. Holding Mr. Lin's hand, Yazi began to cry. The floor was strewn with stains of tears and wine. We then boarded boats. Gradually, we were through with drinking. Moans and howls began to fill West Lake. Then the relentless melancholy set in. It was heartbreaking. [Liu Yazi] suddenly rose and was about to throw himself into the lake. Fortunately he was stopped by Mr. Ding and Chunhang 春杭. (XYH: 23: 6)

Liu confided his agony to a friend in a letter he wrote on the same day:

We boated on the lake and drank ourselves into total oblivion. Awakening, we talked again about national affairs. We cried our hearts out, until our sleeves were drenched with tears. ... When the crying was over, I thought of jumping into the lake to emulate Qu Ping's [Qu Yuan] act of drowning himself. Regrettably, my friends stopped me. (Yang/Wang 1995: 390)

Little of this sound and fury is conveyed in the calm pictures of boating on West Lake. We have every reason to question our assumption about the tranquil state of Huang Yanpei's mind as he took these photographs of a serene landscape in 1914, when the political situation was already dismal and Huang had already withdrawn from politics. It may well be that these landscape pictures had a therapeutic and calming effect on him and his deeply distressed revolutionary contemporaries. It is also true that they nevertheless had the urge to project some of their sentiment onto the world they saw. To this end, photographs of pure landscape could not register the intensity of their emotional rhetoric. Their passion had to find other scenes and settings for its outlet.

Next

Notes:

[1] The English title, Views of West Lake, appears on the front page. It is volume one of what was intended as a multivolume publication. I have not seen the subsequent volumes.

[2] A parallel situation was the publication of school textbooks that the Commercial Press had specialized in before the Revolution. On the eve of the Revolution, some staff suggested to Zhang Jusheng 張菊生, who was in charge of textbook publication, to prepare a new set of primary school textbooks in anticipation of the Revolution. Zhang, a conservative with imperial leanings, discounted the possible success of the Revolution and refused change. Lu Bohong, a senior editor of the press, secretly prepared a new set and, in the first year of the Republican era, broke away from the Commercial Press to found Zhonghua Publishing House, where he published the new textbooks. The sudden change caught the Commercial Press unawares. The old textbooks with their references to imperial rule were instantly discredited and outdated. The Commercial Press had to scramble to come up with new textbooks within a short period (Jiang Weiqiao 1959:

396-399).

[3] Huang also coedited volume one of the three-volume set.

[4] The notion of the 'period eye' is derived from Michael Baxandall (1980: 143-145). My sense of the term is premised on the gap between our visual sensibility today and that of 1910s. Of course, the perceptions of these visitors, individuals with different backgrounds and political viewpoints, vary. This diversity allows us to gauge the complexity of moods and attitudes of the time and to see to what extent they shared

Huang's perceptual preoccupations.

[5] Shi Liangcai, the progressively inclined owner of Shenbao, was a close friend of Huang Yanpei. See Lu Yi 1999: 3-4. I am indebted to Kuiyi Shen for this reference.

[6] A tourist recorded that he left Shanghai at 2pm and arrived in Hangzhou at 6pm (Li 1920).

[7] For a general discussion of the relationship between sites and writing in Chinese culture, see Owen 1986: 16-32.

[8] See, for instance, Strassberg 1994: 342-345, 367-371.

[9] This compositional scheme is first seen in the painting in the Shanghai Museum, conventionally and erroneously attributed to Li Song, that shows a panoramic view of the lake from the east. For discussion of the scroll, see Miyazaki 1984: 209-237.

[10] The present study is hampered by the unavailability of the first edition of the 1910 album. I have to draw on its eleventh edition, published in 1926 by the Shanghai Commercial Press. Of the Ten Views in the new edition, six of them have been replaced with Huang's photographs. The remaining four—looking at Fishes on the Flowery lagoon (XHFJ: pl. 4), A Pavilion of the'Nanping Range (XHFJ: pl. 7), The Three Pagodas Half-Buried in Water (XHFJ: pl. 8), and A Sunset View of the Thunder' Peak Pagoda (XHFJ: pl. 9)—differ from those taken by Huang. It is thereby assumed that they are the plates from the original 1910 edition.

[11] It was built by Qian Hongchu and his consorts in A.D. 976. Qian was the last ruler of Wu-Yue, a state in its twilight days struggling for survival when most of China had been unified by the Song in the north. The pagoda collapsed in 1924. For a study of the history of this pagoda-dominated landscape view. See Eugene Wang's essay on the pagoda, also in Features of this issue.

[12] Again, he acknowledges it as one of the Ten Views only in the caption below the photograph (ZGMS: 1: 10).

[13] Zhang Renmei (1985: 37-42) An eighteenth-century scholar who visited West Lake in 1759, for instance, structured his tour around the Ten Views.

Bibliography:

Baxandall, Michael. 1980. The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cao Wenqu 曹文趣, et al., eds. 1985. Xihu youji xuan 西湖遊記選 (Selected travelogues of West Lake). Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi.

Chen Xingzhen 陳杏珍. 1977. 'Leifengta de mingcheng ji qita' 雷峰塔的名稱及其他 (The name of the Thunder Peak Pagoda and other issues). Wenwu tiandi 6: 40-44.

Chesneaux, Jean, et al. 1979. China from the 1911 Revolution to Liberation. Tr. P. Auster and L. Davis. New York: Pantheon Books.

Dillon, E. J. 1911. 'The Most Momentous Event for 1000 Years.' Contemporary Review (December): 874.

Hu Zushun 胡祖舜. 1949. Wuchang kaiguo shilu 武昌開國史錄 (Record of the founding of the Republic at Wuchang). Wuchang: Jiuhua yinshuguan.

Huang Yanpei 黃炎培. 1914. 'Preface' of West Lake, Hangchow, vol. 1. In ZGMS.

———. 1934. Zhidong (Heading east). Shanghai: Shenghuo.

Jiang Weiqiao 蔣維喬. 1959. 'The Commericial Press and Zhonghua Press in their early phase'. In Zhang Jing l u 張靜廬, ed., Zhongguo xiandai chuban shiliao 中國現代出版史料 (Materials of history of modern Chinese publishing business). Shanghai: Zhonghua, ser. no. 4, 2: 396-399.

Li Tinghan 李廷翰. 1920. 'You Hang ji' 遊杭記 (Touring Hangzhou). In XYH 1920:11-12.

Lin, Shuen-fu. 1983. 'Chiang K'uei's Treatises on Poetry and Calligraphy'. In Susan Bush and Christian F. Murck, eds., Theories of the Arts in China. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lu Ciyun 陸次雲. 1999. Huru zaji 湖*雜記. In Xu Fengji 徐逢吉, Qingbo xiaozhi wai bazhong 清波小志外八種 (Notes on Clear Waves and eight other works) Eds. Shi Diandong 施奠東 et al. Shanghai: Shanghai guji.

Lu Jiansan 陸鑒三, ed. 1981 . Xihu bicong 西湖筆叢 (Writings on West Lake). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin.

Lu Yi 陸詒. 1999. 'Shi Liangcai yu Shenbao' 史量才與申報 (Shi Liangcai and Shenbao). In Lu Jianxin 陸堅心 et al., eds., 20 shiji Shanghai wenshi ziliao wenku 20世紀上海文史資料文庫 (Collection of cultural historical materials of 20th century Shanghai). Shanghai: Shanghai, 6: 1-8.

Miyazaki Noriko. 1984. 'Saiko o meguru kaiga—Nan So kaigashi sho tanichi' (Paintings of West Lake: preliminary exploration of history of painting of Southern Song). In Umehara Kaoru, ed., Chugoku kinsei no toshi to bunka (Urban culture of early modern China). Kyoto: Kyoto daigaku bunjin kagaku kenkyujo, 209-237.

MST. Mingshan tu 名山圖. 1994. In Zhongguo gudai banhua congkan erbian 中國古代版畫叢刊二遍. Shanghai: Shanghai guji. vol. 8. First edition 1633.

Owen, Stephen. 1986. Remembrances: The Experience of the Past in Classical Chinese Literature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

——. 1992. Readings in Chinese Literary Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

——, ed./tr. 1996. Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York and London: vii. W. Norton.

Peng Ziyi 彭子儀 ed. 1941 . Qiu Jin 秋瑾. Shanghai: Yaxin.

A Pictorial History of the Republic of China—Its Founding and Development. 1981. 2 vols. Taipei: Modern China Press.

Price, Don C. 1990. 'Constitutional Alternatives and Democracy in the Revolution of 1911.' In Ideas Across Cultures: Essays on Chinese Thought in Honor of Benjamin I. Schwartz. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Council on East Asian Studies. 223-260.

Qian Yueyou 潛説友. 1983-1986. Xianchun Linan zhi 咸淳臨安志 (Gazetteer of Lin'an compiled during the Xianchun period). In Yingyin Wenyuange siku quanshu 景印文淵閣四庫全書. 1500 vols. Taipei: Taiwan shangwu, vol. 490.

Rankin, Mary B. 1968. 'The Revolutionary Movement in Chekiang: A Study in t h e Tenacity of Tradition.' In Rankin, China in Revolution: The First Phase 1900-1913. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 354-355.

——. 1971. Early Chinese Revolutionaries: Radical Intellectuals in Shanghai and Chekiang, 1902-1911. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schrecker, John E. 1991. The Chinese Revolution in Historical Perspective. New York: Greenwood Press.

Shen Fu 沈復. 1993. Fusheng liuji 浮生六記 (Six chapters from a floating life). Beijing: Shumu wenxian.

Shen Tuqi 沈屠奇. 1982. Xihu gujin tan 西湖古今談 (Notes on West Lake, past and present). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin.

Spence, Jonathan D. 1981. The Gate of Heavenly Peace: The Chinese and Their Revolution, 1895-1980. New York: Penguin Books.

Strassberg, Richard E., tr. 1994. Inscribed Landscapes: Travel Writing from Imperial China. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Tian Rucheng 田汝成. 1980. Xihu youlanzhi 西湖遊覽志 (A travel guide to West Lake). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin.

Wang, Eugene Y. 2003. 'Trope and Topos: the Leifeng Pagoda and the Discourse of the Demonic.' In Judith Zeitlin and Lydia Liu, eds., Materializing Writing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wang Guowei 王國維. 1981. Renjian cihua xinzhu 人間詞話新註 (New annotated lyric meter poetics from the human world). Jinan: Qilu shushe.

Wang Huabin 王華斌. 1992. Huang Yanpei zhuan 黃炎培傳 (Biography of Huang Yanpei). Jinan: Shandong wenyi.

Wang Lu 王露 et al., comp. 1934. Zhejiang tongzhi 浙江通志 (Gazetteer of Zhejiang). Shanghai: The Commercial Press. First edition 1736.

Wright, Mary C. 1968. China in Revolution: the First Phase, 1900-1913. New Haven: Yale University Press.

XHFJ. 1926. Xihu fengjing 西湖風景 (Views of West Lake). Shanghai: Commercial Press. First edition in 1910.

XHZ. 1735. Xihu zhi 西湖志 (Gazetteer o f West Lake). 48 juan. Comp. Wang Lu 王露. Hangzhou: Zhejiang shuju.

XXZ. 1921 . Xihu xin zhi 西湖新志 (New gazetteer of West Lake). Ed. Hu Xianghan. 胡祥翰. N .p.

XYH. 1920. Xin youji huikan 新遊記匯刊 (A collection of new travelogues). Shanghai: Zhonghua.

Xu Hansan 許漢三. 1985. Huang Yanpei nianpu 黃炎培年譜 (Huang Yanpei: a chronology). Beijing: Wens hiziliao.

Yang Tianshi 楊天石 and Wang Xuezhuang 王學莊, comps. 1995. Nanshe shi changbian 南社史長編 (Annals of South Society). Beijing: Zhongguo renmin.

Yang Yi 楊義, et al. 1997. Zhongguo xinwenxue tuzhi 中國新文學圖志 (Illustrated history of new Chinese literature). Beijing: Renmin wenxue.

Yao Wenzhan 姚文栴. 1921. 'Preface.' In XXZ: 4b.

Ye Guangting 葉光庭 and Lü Yichun 呂以春. 1982. Xihu manhua 西湖漫話 (Miscellaneous notes on West Lake). Tianjin: Tianjin renmin.

You Tong 尤侗. 1985. 'Liuqiao qiliu ji' 六橋泣柳記 (Mourning the lost willows on the Six-Bridge embankment). In Cao 1985: 149-151.

Young, Ernest P. 1977. The Presidency of Yuan Shih-k'ai: Liberalism and Dictatorship in Early Republican China. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Yuan Daochong 袁道沖. 1937. 'Hubin jiuying' 湖濱舊影 (Old reflections of lakeshore). Yuefeng Supplement 1. Rpt. in Cao 1985: 62-69.

Zhang Guogan 張國淦. 1958. Xinhai geming shiliao 辛亥革命史料 (Historical materials on the 1911 Revolution). Shanghai: Longmen lianhe.

Zhang Renmei 張任美. 1985. 'Xihu jiyou' 西湖記遊 (Note on touring West Lake). In Cao 1985: 37-42.

Zhao Erxun 趙爾巽, et. al., comps. 1976-1977. Qing shigao 清史稿 (Draft history of the Qing). Beijing: Zhonghua.

Zheng Yunshan 鄭雲山 and Chen Dehe 陳德禾. 1986. Qiu Jin pingzhuan 秋瑾評傳(Critical biography of Qiu Jin). Kaifeng: Henan jiaoyu.

Zhou Feitang 周芾棠, et al., eds. 1981. Qiu Jin shiliao 秋瑾史料 (Historical materials on Qiu Jin). Changsha: Hunan renmin.

Zhou Feng 周峰, ed. 1992. Minguo shiqi Hangzhou 民國時期杭州 (Hangzhou in the Republican period). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin.

Zhu Yanjia 朱炎佳. 1960. 'Wu Luzhen yu Xinhai geming' 吳祿貞與辛亥革命 (Wu Luzhen and the Chinese Revolution). In Wu Xiangxiang 吳相湘, ed., Zhongguo xiandaishi congkan 中國現代史叢刊 (Selected writings on modern Chinese history). Taipei: Zhengzhong.

ZGMS. Zhongguo mingsheng 4: Xihu 中國名勝西湖 (Scenic China series no. 4: West Lake, Hangchow) . Eds. Huang Yanpei 黃炎培, et al. 3 vols. Shanghai: The Commercial Press.

|