|

FEATURES

The Ten Scenes of West Lake | China Heritage Quarterly

The Ten Scenes of West Lake

Xihu Shi Jing 西湖十景

Duncan Campbell

The Australian National University

In the Thirty-eighth Year of the reign of the Kangxi emperor of the present dynasty [1699], during his Southern Tour of that year, the Emperor declared that henceforth 'A spring's dawn breaking upon Su Embankment' [Su di chun xiao 蘇堤春曉] was to be listed first amongst the Ten Vistas of West Lake.

—Liang Shizheng 梁詩正 and Shen Deqian 沈德潛,

West Lake Gazetteer (Xihu zhizuan 西湖志纂, ed.1755)[1]

Over the course of more than a millennium, quite apart from the wealth of historical and geographical treatments of the Lake and its history that have been written, dense layers of cultural sedimentation have settled on West Lake in Hangzhou 杭州西湖. Poetic works, essays, paintings, folk stories have all accumulated around the Lake making it one of the most iconic physical and metaphorical landscapes of China.

There are said to be over thirty West Lakes in China. Hangzhou's West Lake acquired this name (designating its position relative to the city) sometime during the Tang dynasty (618-907). Over time the name gradually replaced a variety of earlier names for the Lake and the Lake itself becoming over time the West Lake.

Initially a lagoon formed when the alluvial deposits of the Qiantang River 錢塘江 dammed the entrance of a bay at its river mouth, West Lake is a small lake—traditionally held to be only thirty li in circumference—surrounded to its north, west and south by low-lying hills, with the city of Hangzhou standing to its east.[2] It is little mentioned before the Tang dynasty, but over time the Lake became something of a palimpsest for two unresolved and intersecting discourses. One revolved around the question of the Lake's utility; was its importance a result of the fact that it acted as a reservoir for the city of Hangzhou and its surrounding countryside or rather because of its scenic beauty? The other discourse concerned the issue of access to (and control of) the Lake itself—the tension between the private (and elite) appropriation of both the Lake's utility and its delights and its centrality within a popular and Buddhist tradition of pilgrimage, for instance.

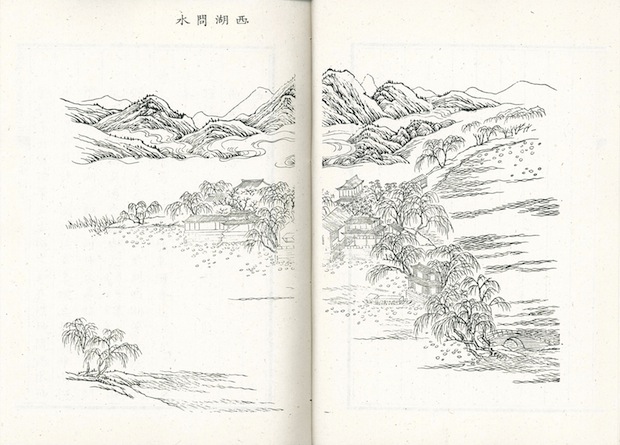

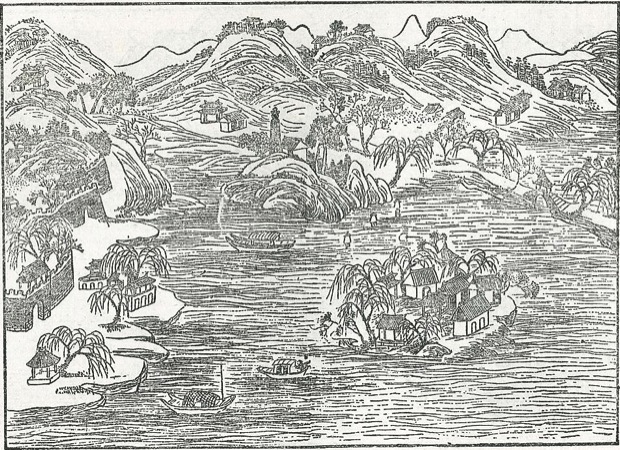

Fig.1 An illustration from Wanggiyan Lincing's Wild Swan on the Snow: An Illustrated Record of My Pre-ordained Life (Hongxue yinyuan tuji 鴻雪因緣圖記)

�

Pervading both of these concerns, or discursive fields, was a practical awareness that the Lake itself relied for its existence on the continuous and prodigious efforts of planners, engineers and an army of workers. 'As is characteristic of Chinese beauty spots', argues the human geographer Yi-fu Tuan, 'the landscapes surrounding the lake, and the lake itself, are largely artificial. The natural scene of the Hangzhou area was a deltaic flat, sluggishly drained by a few streams. Out of the flat alluvium, islands of bedrock obtrude. When the streams were dammed, perhaps as early as the first century A.D., a lake collected behind the dyke so that the basic elements of the Chinese landscape—mountains juxtaposed against alluvial banks and water—were formed'.[3] 'To the casual visitor', Tuan claims elsewhere, 'the West Lake region may appear to be a striking illustration of how the works of man can blend modestly into the magisterial context of nature. However, the pervasiveness of nature is largely an illusion induced by art. Some of the islands in the lake are man-made. Moreover, the lake itself is artificial and has to be maintained with care'.[4]

Perhaps representative of the way that some of these understandings of the Lake were worked out during the late imperial period is the account given of his trip as a youth to Hangzhou to visit the Lake in 1806 by Linqing 麟慶 (the Bannerman Wanggiyan Lincing, 1791-1846), latterly the Director-General of River Conservancy in Huai'an, from Book One of his remarkable collection of autobiographical travel essays Wild Swan on the Snow: An Illustrated Record of My Pre-ordained Life (Hongxue yinyuan tuji 鴻雪因緣圖記):[5]

Paying my Compliments to West Lake[6]

In the first month of the year bingyin [1806], my father was appointed Prefect and assigned to the province of Zhejiang. He proceeded there immediately. In the following month my mother and I accompanied my great-grandmother on the river-trip to the South. When we were about to weigh anchor, I received a poem sent to me as a parting gift by Uncle[7] Ju Shantao 車珊濤.[8] The poem included the following lines:

The year contains so little spring enchantment;

When you visit West Lake, enjoy it to the full.

When I did reach Hangzhou it was already the beginning of the sixth month. Just then Uncle Li Kangjie 李康皆[9] came from Shanyin[10] and invited me to visit West Lake with him. That very day, accompanied by my brother Zhongwen, we went to the Water Pavilion outside the Yongjin Gate[11] of the city, and hired a boat to sail downstream. All around us the hills stood like screens of azure and jet, while purple halls and crimson palaces shone to right and left, as if we could pluck them from our very sleeves. Then we paid our respects at the Temple to the Prince of the Water Immortals.

Evening was approaching as we sailed into the thick of the lotus flowers; we smelt the fragrance of the wind on the gentle ripples of the water, and became oblivious of the cruel heat. I cut a lotus stem and used it as a straw with which to sip my wine. The moon was up by the time we left.

During my days as an official in the Capital, I would recollect this happy experience, and fly there in my imagination.

I have written a series of sixteen 'truncated poems'[12] entitled 'Reminiscences of West Lake', and I beg to append one here:

Outside the Tower to Welcome Auster[13]

the green flow is rich;

Visitors are loath to leave

the fragrance drifting these many miles;

If this moral frame can change

into a butterfly dreaming,

Surely tonight it will fly

around the lotus flowers.

On investigation there are altogether in our Empire thirty-one expanses of water bearing the name West Lake, but the Mingsheng Lake of Qiantang[14] is the most famous. In the ancient Han dynasty, there occurred the miracle of the Golden Cow, as recorded in Li Daoyuan's 酈道元 Notes on the Water Classic.[15] And West Lake is not merely a picturesque scenic spot, it is also a useful source of water. In the Tang dynasty, the Duke of Ye[16] drilled six wells, Bo Xiangshan 白香山[17] constructed stone conduits to irrigate the farm land, and Su Shi of the Song dynasty introduced vegetable farms. The economic benefits of West Lake have been enhanced from age to age. During the Yuan and Ming dynasties, it was left unattended and came to be more and more in need of dredging. In the present dynasty, during the second year of the Yongzheng reign [1724], the Governor of Zhejiang, the posthumously canonised Lord Li Minda 李敏達[18] received an Imperial order to dredge the Lake and make other necessary improvements. The Lake thus came to be of great benefit to the livelihood of the people in the western part of Zhejiang. Moreover the same Governor restored the antiquities and revised the gazetteers. He certainly did much for West Lake, and it is fitting and proper that he should be worshipped together with the Prince of the Water Immortals.[19]

By the late-Ming period in particular, West Lake had become a required stop on the itineraries of literati during their tours of the empire.[20] It was, to their minds, also the best of all possible literary, spiritual or political retreats when they were either out of favour in the capital, tired of their bureaucratic duties or in need of an escape from family pressures. In Dream Search for West Lake (Xihu mengxun 西湖夢尋), extracts of which are translated in the Features section of this issue of China Heritage Quarterly, the late-Ming historian and essayist Zhang Dai 張岱 (1597-?1684) attempted to recreate in prose the West Lake he had known. That extraordinary collection of 'dreamscapes' is not simply a loving description of the sights and sounds of an entrancing, if almost entirely man-made, scenic place; to Zhang and his like-minded contemporaries, the Lake embodied the cultural and philosophical values that they held most dear. It was the summation of a civilisation that, for a few years in the 1640s, seemed threatened with extinction. One could summarise the late-Ming literati sensibility by isolating a number of themes that would seem characterise representations of West Lake during this unique period:

- Writings about the Lake reflected a particular kind of nostalgia, as well as a related sense to do with loss and separation;

- The Lake figured as an escape from the burdens of office, factionalism at court, or family responsibilities, yet it was a 'productive escape' justified through the creation of written or painted works;

- Accounts of the Lake were permeated by a masked but marked sensuality, something reflected in the representation of the Lake as the most beautiful of all women, Xi Shi 西施, or the Lady of the West;

- The delights of connoisseurship are made more intense by the juxtaposition of elite tastes to do with the Lake and its pleasures with popular and religious uses of the site; and,

- Representation of the Lake invariably engaged with the dense tapestry of literary and historical associations that had accumulated over the ages.

To Zhang Dai's mind, the delights of the Lake, like other pleasures in life, 'can provide the gratification of but a moment' (zhi ke gong yike shouyong 只可共一刻受用).[21] Not for him the easy contrast between the fleeting impermanence of human existence and the immutable continuity of the mountains and rivers; as his West Lake anthology so eloquently shows, landscape too is as prone to the vicissitudes of history as is humankind. His pursuit rather was the quality of the enjoyment of the moments afforded by the realm of the senses, and the refinement with which one could depict such moments. This is perhaps most tellingly revealed in Zhang Dai's evocation of the Southern Song period (1127-1279), a time of dynastic crisis when Hangzhou served as capital of the truncated and ever threatened remnants of the Chinese empire. For Zhang it was the time when the Lake was at its most splendid. The implied analogy with the circumstances of his own age, one in which first peasant rebellion and then the Manchu-led invasion of Ming territory cast the empire into chaos, is obvious.

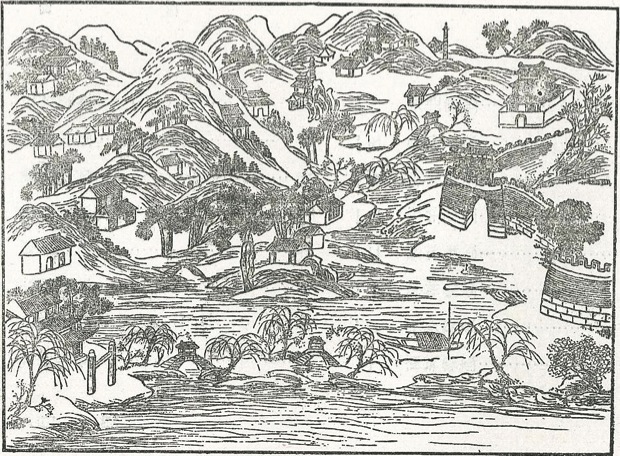

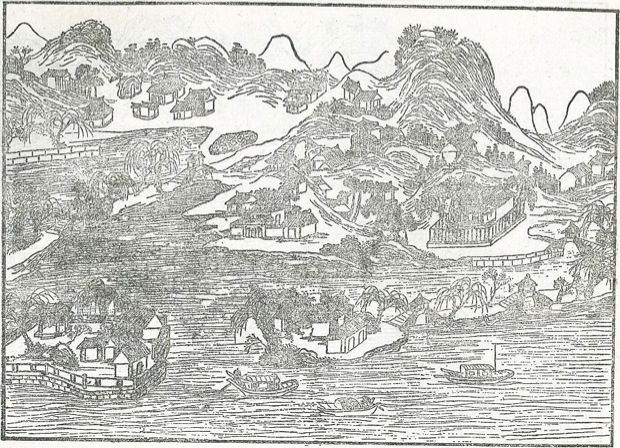

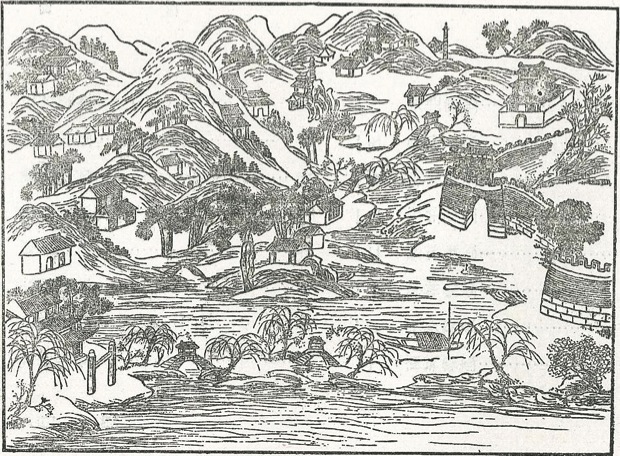

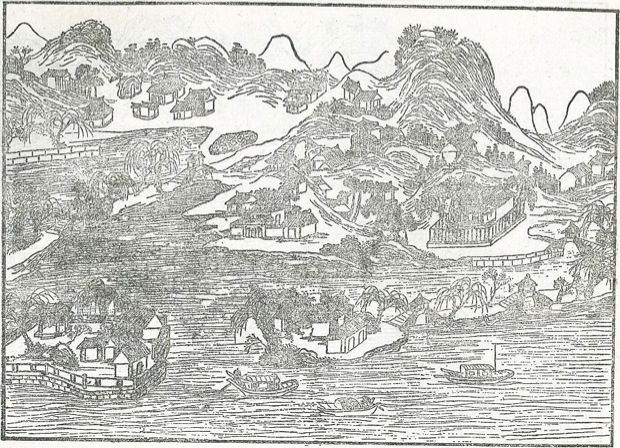

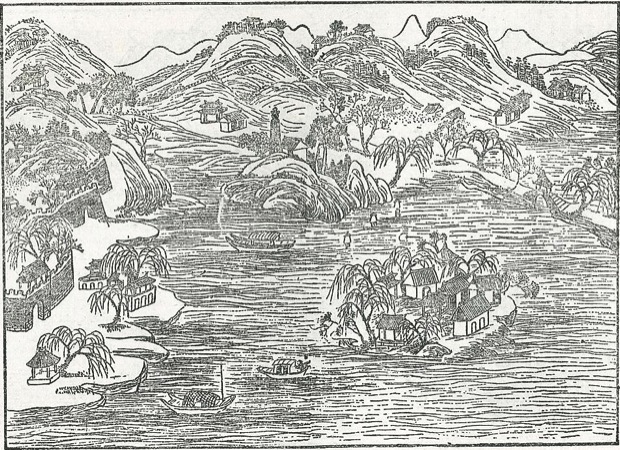

Fig.2 Woodblock print depicting West Lake, Guangxu period.

�

Whatever the literary or historical aspirations of its author, Dream Search was (and indeed is) often read as a guidebook to the West Lake. Zhang Dai encouraged his readers to think of the Lake as a 'stroll garden', with its implication of a 'defined route' and 'sense of destination', part of what John Dixon Hunt describes as a triad of movement through gardens and designed landscapes:

Rambles are for the pleasures of movement itself, without definitive or preordained routes or destinations; a ramble implies impulse, spontaneity, a disconnected wandering, and therefore it is more likely that a ramble is solitary, since one person's disconnections would distract from another's ramble.[22]

There is a further related, if posthumous, irony associated with Zhang's Dream Search. By the time of its first publication in 1717, the Lake had been re-inscribed as the domain of the third mode of movement discussed by Hunt, the procession or ritual, at the hands (or feet) of no less a figure than the Kangxi emperor (r.1661-1722) himself (see Wang Liping's essay in this issue).

Fig.2 Woodblock print depicting West Lake, Guangxu period.

�

During the course of his long reign, the Kangxi emperor embarked on six elaborate and expensive Southern Tours (Nanxun 南巡): in 1684, 1689, 1699, 1703, 1705 and 1707. On an average each lasted for about eighty-six days.[23] Although on the first of these in 1684, only four decades since the Qing established its dynastic capital in the fallen Ming city of Beijing, Kangxi only reached as far south as Nanjing, the itinerary for the subsequent five tours followed an established route that included visits to Hangzhou. Ostensibly conducted as exercises in river inspection and water conservancy, the tours served other purposes as well.[24] They can also be understood as being part and parcel of what in another context has been termed the 'landscape enterprise' of the new dynasty.[25] To this extent they represented the Kangxi emperor's ritualised appropriation of a 'Chinese' empire.

Under Kangxi's 'Imperial gaze', representations of the Lake were irrevocably altered, and this process is found best embodied in the new prominence that the emperor gave to an old and somewhat neglected tradition of West Lake representation—that of the 'Ten Scenes'. In Dream Search, appended to his synoptic history of West Lake, Zhang Dai anthologises his own ten poems on the 'Ten Scenes of West Lake'. He makes little further reference to these scenes however, and certainly does not structure his account of the Lake around them. After Kangxi's Southern Tours however, and in particular following the third tour in 1699, no account of the scenic beauties of the West Lake fails to give prominence to this fixed set of scenes.

Hui-shu Lee provides an useful account of the history of the 'Ten Scenes of West Lake' in Exquisite Moments: West Lake & Southern Song Art where she argues that the 'Ten Scenes' 'manifests an aesthetic common to much of Southern Song painting: what can be described as the articulation of seasonal moods.' In support of this view, she cites an early listing of the scenes, found in Wu Zimu's 吳自牧 Mengliang lu 夢粱錄, completed around 1300. Wu writes (in Hui-shu Lee's translation): 'In recent times the ten most spectacular scenes of the four seasons around West Lake and its mountains have been illustrated by painters. [Here Wu lists the Ten Scenes, in a slightly different order to that found in other sources.] In spring flowers and willows compete in beauty, while lotus and pomegranates bloom in summer. In autumn the fragrance of cassia floats in the air, and in winter jade-like plums bloom amidst the whirling flakes of auspicious snow. The scenes of the four seasons are ever changing, and these things that gratify the heart and give pleasure proceed endlessly apace.'[26]

The process of the codification of a fixed number of scenes is captured in Zhai Hao's 翟灝 discussion of the 'Ten Scenes' in his 1765 Handy Guide to the Lake and its Hills (Hushan bianlan 湖山便覽) where he quotes Zhu Mu's 祝穆 (d.ca.1246) Topographical Guide to Touring Sites of Scenic Beauty (Fangyu shenglan 方與勝覽) to the effect that:

The hills and water of West Lake are surpassingly elegant; throughout all four seasons of the year painted barges ply the Lake and the sound of song and drum is ceaseless. Enthusiasts proceeded to identify and name ten vistas of the Lake, as follows:

Autumnal Moon Reflected in a Calm Lake (pinghu qiuyue 平湖秋月)

Spring Dawn Breaking Over Su Embankment (sudi chunxiao 蘇堤春曉)

Lingering Snow upon Break-Off Bridge (duanqiao canxue 斷橋殘雪)

Glow of Sunset upon Thunder Peak (leifeng xizhao 雷峰夕照)

Evening Bell-toll at South Screen Mountain (nanping wanzhong 南屏晚鐘)

Breeze Amongst the Lotuses of Brewing Courtyard (quyuan fenghe 麴院風荷)

Viewing Fish at Flower Harbour (huagang guanyu 花港觀魚),

Listening to Orioles Amidst Billowing Willows (liulang wen ying 柳浪聞鶯)

Moon Reflected on Three Ponds (santan yinyue 三潭印月)

Twin Peaks Piercing Clouds (liangfeng chayun 兩峰插雲).

As Zhai Hao remarks,

This was the first instance of the appearance of these Ten Scenes in the gazetteers of the site and, judging from the fact that each scene is given a name that comprises four characters, a practice that was initiated by painters, these scenes must have first been the subjects of paintings before they were so named. Zhu Mu himself, along with the painters Ma Yuan 馬遠 [fl. before 1189-after 1225] and the monk Yujian Ruofen 玉澗若芬 [thirteenth century], were all men of the reign of the emperor Ningzong of the Southern Song dynasty [1195-1224]. Ma Yuan, for his part once produced a folio of ink paintings entitled 'Ten Scenes of West Lake', none of which filled the entire surface of the paper, hence earning for himself the epithet 'One Corner Ma' (馬一角), for which refer to the Record of the Painting Academy of the Southern Song [Nan Song huayuan lu 南宋畫苑錄].[27] Amongst the extant paintings of Yujian Ruofen there also exist ten paintings of West Lake vistas, for which see Paintings Examined [Huihua beikao 繪畫備考]. This record by Zhu Mu is perhaps made on the basis of the existence of these paintings by Ma Yuan and Yujian Ruofen and does not claim that these Ten Scenes in themselves serve to exhaust the scenic delights of the West Lake. Later on, men such as Chen Qingbo 陳清波 of Qiantang and Ma Lin 馬麟also made paintings of the Ten Scenes, while Wang Wei 王洧 wrote a shi poem on each of the ten and Chen Yunping 陳允平 produced ten ci-lyrics, thus ensuring that the names of the Ten Vistas were transmitted down to the present age….

In the Thirty-eighth Year of his reign, the Kangxi emperor himself inscribed the names of the vistas, in the process of which he corrected the various discrepancies that had arisen, and the authorities had stelae engraved and pavilions built to house each inscribed stone. All eyes now gazed upon the stelae in admiration and both the sequence of the Ten Vistas and their names were fixed for all time, never to be altered.[28]

Fig.2 Woodblock print depicting West Lake, Guangxu period.

�

'Landscapes', Simon Schama has argued, 'are culture before they are nature; constructs of the imagination projected onto wood and water and rock… But it should also be acknowledged that once a certain idea of landscape, a myth, a vision, establishes itself in an actual place, it has a peculiar way of muddling the categories, of making metaphors more real than their referents; of becoming, in fact, part of the scenery'.[29] Here perhaps, although he does not make reference to it as such Schama is responding to Yi-fu Tuan's elegant discussion of these two words:

Scenery and landscape are now nearly synonymous. The slight differences in meaning they retain reflect their dissimilar origin. Scenery has traditionally been associated with the world of illusion which is the theater. The expression 'behind the scenes' reveals the unreality of scenes. We are not bidden to look 'behind the landscape', although a landscaped garden can be as contrived as a stage scene, and as little enmeshed with the life of the owner as the stage paraphernalia with the life of the actor. The difference is that landscape, in its original sense, referred to the real world, not the world of art and make-believe. In its native Dutch, 'landschap' designated such commonplaces as 'a collection of farms or fenced fields, sometimes a small domain or administrative unit'. Only when it was transplanted to England toward the end of the sixteenth century did the word shed its earthbound roots and acquire the precious meaning of art. Landscape came to mean a prospect seen from a specific standpoint. Then it was the artistic representation of that prospect. Landscape was also the background of an official portrait; the 'scene' of a 'pose'. As such it became fully integrated with the world of make-believe.[30]

In Tuan's terms then, the trajectory of the long history of representations of the Lake saw it move from being simply a Lake, important to the considerable city that it abutted and the fields that surrounded it for the water it collected and supplied, to landscape to be both toured and represented in word and image, and finally to scenery.[31]

The sixty-one year reign of the Kangxi emperor proved one of the longest in all of Chinese history, whilst his 'Grand Enterprise', the Great Qing dynasty, was to last for almost another two hundred years after his death, the extent of its reach greater than that of any Chinese state either before or after it. By contrast, so complete was the obscurity that Zhang Dai had sought for himself, until he was rediscovered in the 1930s, that even the date of his death remains uncertain. The last uncontested date for him is a preface dated the Nineteenth Year of the Kangxi reign, that is 1680—although after the fall of the Ming Zhang Dai refused to mark his passage through time by reference to the emperor and dated his preface in accordance with cyclical notation.

Recent scholarship suggests that Zhang lived on for almost a decade after this date, dying sometime in 1689. This is the very year that the Kangxi emperor undertook the second of his grand Southern Tours and the first that took him to Hangzhou and West Lake. We have an 'un-authorised' insight into this tour in the form of the personal diary maintained by one of the Chinese scholars who accompanied the emperor, the Grand Secretary Zhang Ying 張.[32] Suggestively, given both the Lake's reputation as a provider of sensuous delights and the emperor's predilection for such temptations, the entries for the four days that Kangxi spent there are vague in the extreme: 'Eleventh day: Stayed at Hangzhou. Twelfth day: Snowed heavily',[33] and so on. On the day after he departed from Hangzhou, however, we are told that the emperor proceeded to Shaoxing, Zhang Dai's birthplace, and that the first thing there was to climb to the summit of the Recumbent Dragon Hill (Wolong Shan 臥龍山), the very hill upon which stood (in ruins, by now) the various family gardens where Zhang Dai had spent much of the first half of his life. Sadly, we will never now know if West Lake's quintessential rambler was still alive to the fact that West Lake's new master had come visiting.

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes:

[1] Panshan zhi (wai yizhong) 盤山志(外一種), Shanghai: Guji Chubanshe, 1993, p.351.

[2] For a discussion of both the nomenclature of the Lake and its history, see Zhai Hao 翟灝, comp., Handy Guide to the Lake and its Hills [Hushan bianlan 湖山便覽], (1765), reprint Shanghai: Guji chubanshe, 1998, pp.11-23. On the geological origins of the Lake, see Zhu Kezhen 竺可禎, 'On the Formation of Hangzhou's West Lake' (Hangzhou Xihu shengcheng de yuanyin 杭州西湖生成的原因), in Zhu Kezhen's Collected Writings (Zhu Kezhen wenji 竺可禎文集), Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 1979, pp.18-20; first published in the journal Science (Kexue 科學), (1921), 6(4).

[3] China, Chicago: Aldine-Atherton, 1969, pp.124-5; romanisation altered.

[4] Yi-fu Tuan, 'Discrepancies Between Environmental Attitudes and Behaviour: Examples from Europe and China', in P.W. Englis & R.C. Mayfield, eds., Man, Space, and Environment: Concepts in Contemporary Human Geography, New York: Oxford University Press, 1972, p.69.

[5] For a short biography of Linqing (by Fang Chao-ying), see Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (ECCP)(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1943) , pp.506-506. This section is quoted from Yang Tsung-han, trans. and John Minford, ed., 'Tracks in the Snow—Episodes from an Autobiographical Memoir by the Manchu Bannerman Lin-ch'ing (1791-1846), with Illustrations by Leading Contemporary Artists', East Asian History (1993), 6:131-32; I have retained the annotations given by both translator and editor, marked YTH and Ed respectively, but have altered the romanisation. For two other selections from Linqing's work, see China Heritage Quarterly, No. 17 and No. 21.

[6] YTH: Wen 問 is used here in the ancient classical meaning, to 'pay compliments with a gift', as in 'The Ruler of Wei sends his compliments to Zigong (a notable pupil of Confucius) with the gift of a weapon.' This did not mean that the Ruler of Wei 'asked some questions' about the bow. See also Zuo zhuan, 11th year of Duke Cheng (576 BC).

[7] YTH: The term used here, zhang 丈, is the common Chinese courtesy appellation for a father's close friend or a family close friend of rather advanced age. The word literally means an elder, senior, venerable old man.

[8] YTH: Name Wangdorgi 旺多爾濟, a Mongol and a Student of the Imperial Academy, admitted by Special Grant.

[9] YTH: Name Buying 步瀛, Academy Student from Shanyin, later served as Chief County Education Officer.

[10] Ed: Shaoxing.

[11] Ed: Cf. the lines by Chao Chongzhi 晁沖之 (c. 1090): 'Outside Yongjin Gate you'll be free of the red dust'; and Yu Qian 于謙 (1398-1457): 'Outside Yongjin Gate the willows are like smoke.' Angus Graham's translation in Poems of the West Lake.

[12] YTH: A form of short poem with four lines which is supposed to be an abbreviated or truncated form of the 'regulated verse'. The form was started in the Tang dynasty and almost all the great masters employed it. Many wrote perennially renowned and touching compositions in that form, which became more and more popular in Ming and Qing days. But alas! Waning popularity and lack of inspiration make it a less and less honoured form.

[13] YTH: The auspicious South Wind which symbolises Well-being and Happiness.

[14] YTH: A variant name of Hangzhou.

[15] Ed: Li Daoyuan (d.527).

[16] YTH: Li Bi 李泌 (722-89), a fascinating, enigmatic and talented character in Chinese history.

[17] YTH: The courteous name for Bo Juyi 白居易, the famous poet and renowned civil administrator of the Tang dynasty.

[18] YTH: Name Wei 衛, Provincial Academy Student of Jiangsu. Ed: Hummel, or rather Fang Chao-ying, in his biography of Tian Wenqing, gives Li's dates as (?1687-1738), and leaves a somewhat different impression of the man: 'A provincial official highly favoured by Emperor Shizong (Yongzheng)…. Although in his term at Hangzhou he improved greatly the architecture and scenic beauties of West Lake, he saw nothing incongruous in having an image of himself placed in the main hall dedicated to the Spirit of the Lake, a divinity known also as the Spirit of the Flowers. In a smaller structure to the rear of this image was placed a group of figures representing himself and his wives. When, some five decades later (in 1780), Emperor Gaozong (Qianlong) visited Hangzhou he ordered these figures removed and replaced by others more in harmony with the Spirit of the Lake.'

[19] YTH: First of all, this has nothing to do with the narcissus, though the narcissus is regularly known as shuixian hua. Here shuixian 水仙 means the various Immortals of the Water, just as there are Immortals of Heaven and of Earth. Some of the most famous Immortals of Water were formerly mortals, e.g. Wu Yun 俉員 and Guo Pu 郭璞. But the Prince of Water Immortals here is not a former mortal. In the Sung dynasty there was a Temple for the Prince of Water Immortals which was actually a Temple for the Dragon King in Hangzhou, near the small temple for the poet Lin Bu 林逋 (967-1028). When Su Shi was the Civil Administrator of Hangzhou, he ordered Lin Bu be worshipped together in this Temple of the Prince of Water Immortals. Hence the temple is mentioned in Huang Tingjian's 黃庭堅 poetical works. So here you have a happy marriage (or ridiculous confusion) of Taoist religion, popular folklore, poetic licence, official arbitrary power and cultural diversion and amusement.

[20] For recent discussion of these 'elite itineraries', see Tobie Meyer-Fong, Building Culture in Early Qing Yangzhou, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2003).

[21] 'Peng Tianxi as Performer' (Peng Tianxi chuanxi 彭天錫串戲), in Xia Xianchun and Cheng Weirong 程維榮, eds., Tao'an mengyi/ Xihu mengxun 陶菴夢憶·西湖夢尋, Shanghai: Guji Chubanshe, 2001, p.93.

[22] John Dixon Hunt, ' "Lordship of the Feet": Toward a Poetics of Movement in the Garden', in Michel Conan, ed., Landscape Design and the Experience of Motion, Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, 2003, pp.187-213.

[23] Kangxi also undertook tours to the other quarters of his empire. For a discussion of these imperial tours, see Jonathan D. Spence, Ts'ao Yin and the K'ang-hsi Emperor: Bondservant and Master, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988, pp.124-57. His grandson, the Qianlong emperor (r.1736-95), also undertook six Southern Tours (in 1751, 1757, 1762, 1765, 1780 and 1784). He later claimed to regret his extravagance in this respect, for which see Harold L. Kahn, Monarchy in the Emperor's Eye: Image and Reality in the Ch'ien-lung Reign, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971, p.96. For an illustrated discussion of a guidebook to West Lake produced for the Qianlong emperor in about 1770, see Philip Hu, 'Map of the Detached Imperial Residence on the West Lake', in his Visible Traces: Rare Books and Special Collections from the National Library of China, New York: Queens Borough Public Library, 2000, pp.189-92.

[24] For a recent treatment of the historiographical issues associated with the Southern Tours of the Qianlong emperor in particular, see Michael G. Chang, 'Fathoming Qianlong: Imperial Activism, the Southern Tours, and the Politics of Water Control, 1736-1765', Late Imperial China (2003), 24(2): 51-108; and his subsequent monograph, A Court on Horseback: Imperial Touring and the Construction of Qing Rule, 1680-1785, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center/Harvard University Press, 2007.

[25] On this, see in particular Philippe Forêt, Mapping Chengde: The Qing Landscape Enterprise, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2000; and Laura Hostetler, Qing Colonial Enterprise: Ethnography and Cartography in Early Modern China, Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 2001.

[26] See Hui-shu Lee, Exquisite Moments: West Lake & Southern Song Art, New York: China Institute, 2001, p.32. In a celebrated essay written in 1925, the great modern Chinese writer Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881-1936) had considerable fun at the expense of this tradition of what he labels the 'ten-sight disease', for which see his 'More Thoughts on the Collapse of Leifeng Pagoda', in Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, trans., Lu Xun: Selected Works, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1985, vol.2, pp.113-18. For a recent treatment of this essay, and of Thunder Peak Pagoda generally, see Eugene Y. Wang, 'Tope and Topos: The Leifeng Pagoda and the Discourse of the Demonic', in Judith T. Zeitlin and Lydia H. Liu, eds., Writing and Materiality in China: Essays in Honor of Patrick Hanan, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003, pp.488-552, reprinted in this issue of China Heritage Quarterly. For a recent discussion of the concept 'Scene' (jing 景), see Hui Zou, A Jesuit Garden in Beijing and Early Modern Chinese Culture, West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 2011. He writes: 'The term jing, which can be translated as "scene" in English, is a classic concept of Chinese garden design. According to the first Chinese garden treatise, Yuan ye (The Craft of Gardens), when the spectator's eyesight touches a jing, wonder will emerge; when his emotion is contained in viewing a jing, the jing will become fruitful. A jing can integrate a garden scene and the spectator's mind into one unity, where the diffusion of brightness is the very flow of passion.'(p.13)

[27] For a note on this work, compiled by Li E 厲鶚 (1692-1752) and published in 1721, see Hin-cheung Lovell, An Annotated Bibliography of Chinese Painting Catalogues and Related Texts, Michigan Papers in Chinese Studies #16, AnnArbor: The University of Michigan, 1973, pp.45-46.

[28] Hushan bianlan, pp.27-28.

[29] Simon Schama, Landscape & Memory, London: HarperCollins, 1995, p.61.

[30] Yi-fu Tuan, Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974, p.133.

[31] For two excellent treatments of the plight of West Lake during the Republican era (1911-49), see Liping Wang, 'Tourism and Spatial Change in Hangzhou, 1911-1927', in Joseph W. Esherick, ed., Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900-1950, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2000, pp.107-20; and Eugene Y. Wang, 'Perceptions of Change, Changes in Perception—West Lake as Contested Site/Sight in the Wake of the 1911 Revolution', Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, (2000), 12(2):73-122, both of which are also reprinted in this present issue of China Heritage Quarterly.

[32] For a short biography of Zhang Ying (1638-1708), by Fang Chaoying, see ECCP, pp. 64-65.

[33] Zhang Ying, 'A Brief Record of the Retinue on the Southern Tour' (Nanxun hucong jilüe 南巡扈從紀略), in Zhaodai congshu, vol.2, p.918.

|