|

||||||||

|

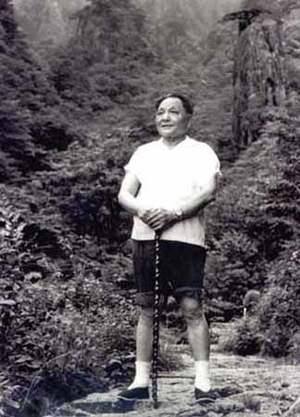

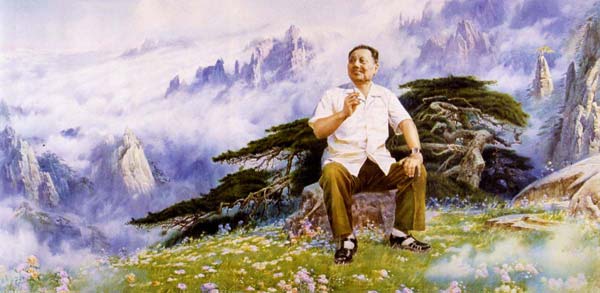

FEATURES1979: Huang Shan, Selling Scenery to the BourgeoisieAn Oral History Account of Chinese Tourism, 1949-1979By Sang YeEdited and translated by Geremie R. Barmé Deng Xiaoping at Huang Shan, July 1979 In July 1979, Deng Xiaoping visited Huang Shan 黄山 in Anhui province. It was only some months since the Chinese Communist Party had formally initiated policies that gave economic development precedence over ideological rectitude. During his trip the Party leader mixed politics with leisure. A famous photograph shows the seventy-five year old Party tourist, pant legs rolled up, standing crop in hand with the famous scenic mountain behind him. During his time at the mountain retreat he stayed at the Villa For Viewing the Waterfall (Guanpu Lou 观瀑楼), and his room and other venues related to his historic visit were later turned into a small museum. At the time Deng gave an influential speech on the money-generating potential of tourism. Known as the 'Huang Shan Talks' (Huang Shan tanhua 黄山谈话), Deng Xiaoping's remarks marked a turning point in China's modern tourist industry; they also proved to be a key moment in the development of the country's heritage industry. Yang Zhiyuan 杨志远 was seventy-two at the time he gave this interview in late 2008. He was a former manager of the China International Travel Service, the official Chinese tourist agency. He was also a specialist in the history of tourism. Among other things Yang shows how thoughtful bureaucrats in even the most invidious era of communist politics attempted to use official directives to justify rational policy decisions. For those familiar with the implementation of Maoist-era travel policies, Yang provides sardonic insights into the paranoid system of control that was in sway for over thirty years. In this context, it is also useful to consult Anne-Marie Brady's important book, Making the Foreign Serve China: Managing Foreigners in the People's Republic (2003). This is an edited chapter from the book by Sang Ye and Geremie R. Barmé, The Rings of Beijing: Inside China's Olympic Aura (forthcoming 2010). The full chapter contains material on the pre-1949 Chinese tourist industry as well as other remarks on the surveillance of foreign tourists in the 1960s and the effects on the industry of the events of 1989. This material is based on an oral history interview by Sang Ye, edited and translated by Geremie R. Barmé, and undertaken as part of an Australian Research Council-funded Federation Fellowship project on 'The Spectacle of Beijing'. The translator would like to acknowledge Linda Jaivin's extensive work in helping revise this text. For an earlier moment in the history of Huang Shan, see Stephen McDowall's essay 'Landscape, Culture & Power: The View from Seventeenth-century Yellow Mountain' in the Articles section of this issue. Tourism is an industry; travel agencies are in the business of providing a service to the paying public. It's common sense, but in China we struggled with this simple concept for three decades. It wasn't until Deng Xiaoping made a speech about it at Huang Shan in 1979 that this basic principle was sorted out. Then it took another three decades to get it right in practice. … … A Clean SweepIn the spring of 1949, before the founding of New China, Chairman Mao had only just entered Beijing when he issued a directive that we had to 'clean the house out before inviting guests in'. What this meant was that we were to exterminate counter-revolutionaries on the one hand and expel foreign companies and organizations active in China or pressure them to leave on the other. We got rid of all the foreign-run travel agencies, of course. Some were run out of China, others were left to wither away from the lack of business, with the sole exception of those affiliated with our big brother in socialism, the Soviet Union. While all this was going on, we ought to have been establishing our own travel agencies, but we didn't. No new organizations were set up to deal with foreign visitors—or locals for that matter. All we had was an Overseas Chinese Service Agency created to assist overseas Chinese returning to visit relatives and needing to exchange foreign currency. At the time, there was no need for special services for foreign tourists as foreign tourists couldn't get into the country; they couldn't even get a visa. For the most part, only three kinds of people could enter China: guests of the Communist Party, who were received by the Party's External Liaison Department; government visitors under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and Foreign Experts from the socialist fraternity [the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc], who were the responsibility of the Experts Bureau of the State Council. Only a very few other visitors were permitted entry, and of these only a minuscule number came from the capitalist countries. The Friendship Association looked after the 'friendship delegations' among them and the External Cultural Committee oversaw groups visiting as part of our United Front cultural work. The only real tourism that existed was when foreign diplomats stationed in China went on holiday. Every year the Ministry of Foreign Affairs organised for them to spend time at the old seaside resort at Beidaihe 北戴河 or the West Lake in Hangzhou 杭州西湖. Beidaihe or West Lake: that was it. It's like when you travel cattle-class on an airplane today: they put on a show of giving you a printed menu with your 'choice' of chicken or fish. But it's only ever chicken or fish. Take it or leave it. There are no other options. In addition, there was the odd delegation from fraternal socialist countries organised by the Soviet Union's Intourist Travel Agency. There weren't that many of these, however, and they weren't bona fide tourists either: they were 'progressive groups' travelling on the public purse. Easy: workers' delegations went to the Workers' Union; model students sought out the Youth League, heroic mothers were the province of the All-China Women's Federation. They were all matched up and off they went. There was even less need for a travel agency to serve the domestic market. The only sort of 'travel' [lüxing 旅行] Chinese people did was government-funded trips on official business. When Party or state leaders travelled on business or took a holiday the relevant city or provincial Reception Office [jiaojichu 交际处] would look after them. If the average person ventured to another city or town, they'd be lucky to find a small hostel to spend the night. People had no concept of tourism or travel agencies and right up to the start of the reform period, didn't dare think much about it either. Even a visit to your native place from the city you lived in couldn't be done without a travel permit [lutiao 路条]. Business travel required a letter of introduction [jieshaoxin 介绍信]. You wouldn't even dream of freely travelling a hundred miles from where you lived, much less overseas. China Travel Takes the Wrong RoadBy 1954, our house had pretty much been cleaned up. It was time, gradually, to open the door to guests and the China International Travel Service [CITS, Zhongguo guoji lüxingshe 中国国际旅行社, known as Guolü 国旅 for short] was established on the basis of a formal proposal made by the International Activities Committee of Party Central that was approved by Premier Zhou Enlai, who was in charge of China's foreign affairs. From then until the launch of the Open Door and reform policies a quarter of a century later ours was the only organization in China that dealt with foreign tourists. But CITS was a foreign affairs unit answerable to the State Council. Our brief was to deal with 'international friends' [guoji youren 国际友人], people on exchanges and self-funded travellers not there by official invitation. In reality, we looked after those who weren't covered by various other official organizations, even if we were ostensibly in charge of tourism in China overall. This was the case right up to the time that the State Council established the Tourism and Travel Industry Management Bureau in 1964. Even then, from day one the State Council decided that the bureau was to be placed under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Things were rotten from the start. The new bureau theoretically marked a division between the state bureaucracy and the travel industry; in practice the same people worked for both CITS and the Tourism Bureau. It was simply that CITS dealt with foreigners and the Tourism Bureau managed the industry. The split finally came in 1982; two years later we were freed from our foreign affairs brief and became a business in our own right. At the time, in addition to having its head office in Beijing, CITS established regional offices in twelve cities: Shanghai, Tianjin, Guangzhou, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Wuhan, Nanning, Harbin, Shenyang, Dalian, Dandong and Manzhouli…. The first six were traditional tourist destinations, the latter six a response to the needs of groups from the Soviet Union, Korea and Vietnam. After graduating from Nankai 南开 University [in Tianjin] in 1957, I was assigned to the Guangzhou branch of CITS. I've worked in the system ever since. My first job was a real wake-up call. On the eve of Chinese New Year in 1958, Party Central decided to invigorate local autonomy by handing over control of the regional CITS branches to the local governments. So instead of taking orders from head office in Beijing we were now under local direction, with Beijing only supervising the work. Great! Overnight I'd been demoted from being an employee of the central government to working for a province. I was young and seriously dejected. I passed a cheerless Spring Festival that year. My studies had been unrelated to my job—universities didn't offer courses in hospitality back then. If I'd specialised in foreign languages there would have at least been some connection, but I'd studied history. As a northerner I was never that happy being sent to the south, and for that sort of job no less. And now I'd gone from the Central Army to a guerrilla outfit. But back then we were pretty compliant and did as we were told. The Anti-Rightist Movement had just concluded [when the Party first invited criticism from non-Party members and then punished the critics harshly]. If you had any gripes you didn't dare express them openly. To be fair, there were advantages to letting local authorities run regional tourism. They were far more enthusiastic now that they derived direct benefit from it. In fact, provincial and city governments all over the country applied to be able to receive foreigners or to expand the places accessible to travellers. CITS offices multiplied accordingly; within a year the original twelve had grown to thirty five. Then the Three Years of Difficulty [the Great Leap Forward and its aftermath, including the Great Famine] struck and all industries were ordered to 'adjust, consolidate, rebuild and improve' [tiaozheng, gonggu, chongshi, tigao 调整,巩固,充实,提高]. In reality, everything stagnated. By the time the difficulties passed, there were forty-six branches of CITS around the country. That just about brought us back to where things were before the Second World War with the old China Travel Service.  Out of Bounds for Foreigners Without Special Permits/ 外国人未经许可不准超越 In March 1958, warning notices like this were set up around restricted areas in the limited number of Chinese cities that were open to foreigners. This was done in accordance with the State Council's 'Additional Regulations Concerning the Management of Foreign Travellers in China'. In February 1964, following a Ministry of Public Security meeting held to discuss the management of foreigners, also known as the 'Tianjin Meeting' because it was held in that city, the boundaries around the areas in which foreigners in China were free to move were redrawn to restrict freedom further. In the case of Beijing, foreigners were now only allowed to travel within a twenty-kilometre radius of Tiananmen. For Hangzhou the limit was set at the Qiantang River just outside the city (the so-called 'North Line', or beixian 北线), and so on. Numerous notices of the kind illustrated here were set up to create such 'cordons sanitaires'. In April 1984, following the 'Beijing Meeting' which was held in the capital under the auspices of the Ministry of Public Security, those earlier restrictions were lifted, although control was still strict. This included the continued deployment of some 116 warning notices set up on roads leading to the outskirts of Beijing and to sensitive military areas. In November 1984, the Ministry of Public Security issued its 'Rules Concerning the Reform of the Management System of Entry to and Exit from China'. The last item in this document consisted of a statement that, 'Henceforth, the Ministry of Public Security will no longer employ "Out of Bounds for Foreigners Without Special Permits" notices.' Accordingly, the notices were removed through the following year. The last of the notices to be taken down—that originally set up at the crossroads at Baijia Tong in the western suburbs—was listed as a Grade Three National Heritage Artefact. It is now on display in the Beijing Police Museum.  Still 'Out of Bounds for Foreigners Without Special Permits' In December 2007, the Beijing Government set up this notice not far from the entrance to the Beijing Military Region Headquarters in the western suburbs of the city. While the Chinese message was the same as in the old days, the English had been revised to read, 'Foreigners are forbidden to pass without permission.' The appearance of this notice led to considerable speculation in the media and among citizens that China was taking a step backward, or that it was a single that the authorities were preparing for a difficult Olympic Year in 2008. Others were far more practical and complained that, as the entrance to the sensitive military zone was some one hundred metres away from the sign, local traders (supermarket, shops and vegetable market) would be adversely affected by it. Perhaps it was just a bellwether of the more radical 'Safe Olympics Action Plan' initiated the next year, elements of which have remained in force for 2009, the year of anniversaries. But then it was 1966 and the Cultural Revolution was upon us. Truth be told, our troubles began well before that, in 1964. That's when the Party launched a ['Socialist Education'] movement exhorting everyone 'never to forget class or class struggle'. All foreigners, be they diplomats or tourists, were put under strict surveillance. The government redrew the out-of-bounds zones around the cities; signs appeared everywhere forbidding foreigners entry. They even brought back 'inspection stations' for foreigners [check points in and around cities]. This made the development of tourism rather difficult. Take Beijing, for instance. By then I'd been reassigned to work in the head office there. Originally, foreigners could travel up to forty kilometres from Tiananmen Square. Now, suddenly, this shrunk to twenty. Forget the Great Wall at Badaling 八达岭, you couldn't even get past the 'no foreigners without permits' signs to reach the Fragrant Hills. ….Our travel agency wasn't a business, it was an arm of foreign affairs. So from day one we'd taken the wrong path. Back in 1954, the State Council ruled that 'the aim of tourism is to enhance China's political influence and propagate the achievements of socialist reconstruction. 'Tourism,' it said, was 'an integral part of diplomatic work'. Funding would be 'allocated by the Ministry of Finance to support foreign guests to travel in China. All foreign currency earned by CITS is to be passed back to the Ministry of Finance.' The practical result of these policies was that in its first twelve years of operation, [beginning in 1954, to 1966] CITS hosted fewer than 20,000 foreign travellers, around one-thousandth the number we now get coming to China annually. For the first six of those twelve years we slavishly followed the Soviet Union model and only hosted 'our own kind': that is people from the socialist bloc and friendship delegations from neighbouring countries. As they were all pretty hard up they weren't even bona fide tourists. They either came as 'exchange delegations', or the budgets for them were fudged. You never saw any real money. By around 1960, the socialist bloc was gradually falling apart. With supreme caution, we started hosting an extremely small number of self-funded travellers. A travel agency survives because of the number of tourists it has on its books; if there are only a tiny number of those then it goes without saying that you're not going to be seeing any hard cash. So, despite having forty odd branches throughout China, in over twelve years CITS only handed the Ministry of Finance some US$700,000, plus two million roubles. Even those roubles weren't real money, but 1.2 million US dollars worth of Soviet foreign trade certificates. So over 1,000 people working for twelve years, catering to less than 20,000 customers and making less than US$2 million. Pathetic, isn't it? That's not the worst, though: that two million was not net profit, it was merely what we'd made in foreign currency earnings. It didn't include any of our own expenses: our salaries, the subsidisation of travellers in China, and so on and so forth. If we'd set our expenditures against our 'earnings' we would have gone bankrupt nearly a dozen times over. But, then again, how could we ever go bankrupt? The Party and state had entrusted this branch of foreign affairs to us, and diplomacy is a costly business, not a profitable enterprise. So, although every industry and profession in China can lament the destructive impact of the Cultural Revolution and the Gang of Four on their business, strictly speaking, it doesn't work quite that way for us. During the Cultural Revolution [Mao's wife] Jiang Qing did say, 'You [CITS] are exporting our scenery; in allowing the Western bourgeoisie to enjoy the mountains and rivers of China you're selling out the nation'. But that was merely one fatuous comment among many; just one bit of noise at a time when everything was drowned out by static. Fortunately, we were considered a branch of foreign affairs, and Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou never let her meddle in foreign affairs. She was farting in the wind. CITS was destroyed well before the Gang of Four even became a gang, though in fact, there wasn't really much to destroy in the first place. Selling Scenery to the BourgeoisieDespite our whole-hearted efforts on the diplomatic front, when the Cultural Revolution struck we were still denounced as having carried out the 'reactionary bourgeois line' of having put earning hard currency ahead of politics. That's what Premier Zhou Enlai said, anyway. In 1967, he steadfastly supported the efforts of the revolutionary rebels within CITS to smash the organization as we knew it. He said that foreign countries used tourism to make money, but that our policy was completely different. We were not interested in petty cash. 'Even before the Cultural Revolution it was wrong of you to try to make money from foreign travellers. We're not interested in foreign currency, only sympathy for our cause and the support of travellers for world revolution.' But if you want to generate sympathy and you don't want to make money, how do you go about it? Zhou said:

These people had no money and had never considered coming to China. If you're determined to invite them, you're going to have to foot the bill. We covered all the expenses of such delegations that were invited China. In some instances, we even paid for their travel to and from China. As a result we ended up hosting groups of extreme leftists and radicals from every country. Delegations from the Japanese Red Army, the Palestinian Liberation Front and the Black Panthers came visiting, proudly enjoying song-and-dance parties with Red Guards, with whom they exchanged revolutionary experiences, and received presents of Chairman Mao's works and presented treasures of their own. These groups weren't called tour groups. After all, tourism was revisionism, and travel was about bourgeois scenery. You wouldn't dare call them tour groups—what you did call them was a matter of negotiation. The more humble ones would call themselves 'Study Groups'; the more self-important—those who didn't think they had anything to learn—titled themselves Inspection Tours. The worst were the leftists from little Japan; they really knew how to lay it on thick with names like 'A Group Visiting China to Pay Respect to the Great Leader Chairman Mao'. It made your flesh crawl. Since none of them had to pay for themselves they flooded in, delegation after delegation, to inspect, study and pay respects—hundreds of them. It was quite a phenomenon. Most weren't the least bit interested in seeing any tourist sites. Some even requested not to visit the Great Wall or the Summer Palace. They just wanted to go to Tiananmen Square. Of course, even if they'd wanted to see the Imperial Palace they couldn't: it had been closed for the duration of the revolution. Most of the delegations spent their time in Beijing. If they did go elsewhere it wasn't to traditional scenic cities like Suzhou, Hangzhou and Guilin, but rather to the Three Revolutionary Holy Sites of Yan'an 延安, Shaoshan 韶山 and Jinggang Shan 井冈山. Zunyi 遵义, the other major Holy Site, was off limits as it was on the Third Defence Front and not accessible to foreigners. Those groups given a smaller budget could visit places around Beijing, like the Shashiyu People's Commune [Shashiyu renmingongshe 沙石峪人民公社], which had been extolled by Chairman Mao. Unbelievably, this ridiculous state of affairs continued for nearly two years, right up to the time that the whole country was put under the control of the People's Liberation Army. With that everything came to a complete standstill so that we could throw ourselves into 'struggle, criticism and reform' [dou, pi, gai 斗批改]. We struggled. We criticised. But what were we supposed to do to reform? They sent us off to cadre schools in Hubei and Jiangxi to plant crops and weed out the non-existent 'Counterrevolutionary May Sixteenth Clique' [a spurious conspiracy supposedly aimed against Zhou Enlai]. This situation continued until 1971 by which time things throughout the country were beginning to settle down a bit. Then the martial law committee of CITS reported to the Centre that they were preparing to start up the organization again. They didn't dare call the work we did 'tourism' [lüyou 旅游], preferring the term 'travel' [lüxing 旅行]; the point was we could start hosting foreign travellers again. The report figured that 800 to 1000 travellers could be accommodated in the first year. This number would be made up of leftists from various countries as well as workers, peasants, students and teachers selected from international 'friendship groups'. No one dared approve the report. It had to be sent on up to Chairman Mao for his consideration. The Chairman said that in general its recommendations were acceptable, but that a few rightists could also be given permission to enter China, as well as thirty Americans. Everyone was astounded by the Chairman's directive. What was this all about? How come the sudden turnaround? Now, of course, we realise that the Chairman was thinking about how to get us out of the international quagmire we'd landed in because of the Cultural Revolution and our staunch anti-revisionist stance. He was thinking of how best to revive our relationship with the US. He had a game plan—but how were we to know that? Whatever the motivation, in practical terms this loosened the restrictions we'd been working with, including not being allowed ever to issue visas to Americans and, since the inception of the Cultural Revolution, not to let rightists into China. Make Them Pay to be EducatedIn 1972, the military committee at CITS was removed and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs delegated Yang Gongsu 杨公素 to head the Tourism Leadership Small Group. That meant in reality that he was the head of the China Tourism Bureau and CITS. Yang had been a graduate scholar at the old Yanjing [Yen-ching 燕京] University and he'd served as China's ambassador to Nepal. He was very clear-headed. Upon starting the new job he asked the Ministry of Foreign Affairs what they wanted the travel service to do: was it a business or just a branch of diplomacy? The response he got wasn't what he'd been hoping for: they said that politics was in command and that our mission was political. So he referred the matter to Premier Zhou Enlai. Concerned that the ministry's stand hadn't carried enough weight, Zhou added:

The first sentences were nothing new, if even more extreme than the usual leftist line. But we grabbed on to the comment that we could 'permit a small number of non-friendly individuals to visit China if they are willing to pay their own way.' The Cultural Revolution restriction on self-funded tourism was officially over and we were back in business. In 1973, CITS hosted 3,500 tourists. Our method of compiling statistics was risible. Not only did we count the number of travellers, we also had to categorise them by political standpoint. Of the 3,500, we counted 400 as 'leftist friends' and 114 'right-wingers'; the rest were 'ideologically middle-of-the-road'. The majority came in self-funded tour groups, the most we'd ever hosted. From the start of the Cultural Revolution [in August 1966] to the end of 1973 we'd only had a total of 13,000 foreign visitors. During that time there were two years for which it is impossible to give any clear breakdown of expenses as we'd invited so many leftists and 'friends' from the working class. After that we'd shut down entirely for two years. In the three years following we pulled in US$2 million, though that's before deducting our own costs in Renminbi. In reality, the more visitors we had, the more we were out of pocket. It's like the saying: look well fed by punching your own face till it's swollen. A banquet of eight dishes with soup plus Peking Duck cost five Renminbi a head. A night in the Peking Hotel was a little over ten. Even the self-funded tours cost us money. Although the previous bans on hosting rightists and self-funded tours were gone, we still had to work out a sensible pricing regime. We couldn't keep throwing money away on self-promotion; the state simply couldn't afford it. Anyway, the majority of our visitors were no longer from fraternal socialist nations but middle-of-the-roaders and rightists from bourgeois countries. Why should we, the proletariat, be letting them take advantage of us like that? Not only the Tourism Bureau, but even the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said we had to stop losing money hand over fist. We were to earn 'an appropriate amount of foreign currency'—a slippery expression for sure, but that of Zhou Enlai himself. His actual words were, 'Appropriate fees should be charged; you can't keep losing money'. Hearing that, you couldn't help but feel bamboozled: as though it hadn't been wrong for them to turn a travel agency into an arm of foreign policy but rather our fault for somehow forgetting to collect any money for our services! Anyway, the political winds were shifting and the central authorities didn't want us to keep losing money. We took advantage of the winds of change to set up a new pricing regime. We implemented it in the spring of 1974. That year we hosted 10,000 visitors, making US$3.7 million. In 1975, there were 17,000 visitors and we made US$6.4 million; in 1976 it was 21,000 and US$8 million. This is why some people claim that the turning point for the Chinese tourism industry came before the Reform era [initiated in late 1978], in the last years of the Cultural Revolution. They say it was a result of Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou's policy encouraging people-to-people diplomacy. But I think it's contradictory to want to be both a business and an arm of state diplomacy—get over it. Besides, you call that business? It was nothing like a business. During those years, foreign tourists came to China but we did nothing to service their needs or desires. There wasn't a drop of Coca-Cola anywhere; ninety percent of places didn't serve cold beer and, except for a few hotels in Beijing and Shanghai, no one had ever even heard of espresso or cappuccino. In most places the best you could get was Hainan coffee, and that was always served tepid. There were only thirty-two cities open to foreigners, fewer than the forty-eight we'd had back in 1958. And the tourist visas we issued only covered Beijing and its environs. If they wanted to get to any of the other thirty-one open cities they needed a special travel permit [lüxing xukezheng 旅行许可证] co-issued by the local Foreign Affairs Bureau and Public Security. That rule didn't just apply to tour groups, either: even ministerial delegations of foreign governments required permits to travel out of Beijing. The only exceptions were heads of state and premiers. Tourists were stuck in Beijing without one of those permits, and they weren't allowed to move an inch away from their groups, either. Our CITS guides held onto the permits like glue. Apart from the usual Sacred Revolutionary Sites, the average tourist was allowed to go to Shanghai, Tianjin, Nanjing, Guangzhou, Xi'an, Wuhan, Changsha, Hangzhou, Suzhou and Wuxi. Those from friendly countries were also permitted to visit Shenyang, Anshan and Fushun. Upon request other places could be considered, such as, Kunming, Nanning, Daqing 大庆, Dazhai 大寨 and the Red Flag Canal [Hongqi qu 红旗渠] in Henan. But permits were considered on a case-by-case basis and there was a system of special treatment for some. Even in the supposedly open cities the average tourist couldn't have much fun. Many of the most famous scenic spots weren't open to the public and every city had numerous restricted zones. They could walk along the main streets but not side streets or alleys. We had a saying for this kind of boring tourism: 'Visit temples during daylight, rest at the hotel all through the night' [baitian guang miao wanshang shuijiao 白天逛庙晚上睡觉]. Even that was an exaggeration: they couldn't get away with just visiting temples. In Suzhou they first had to visit the Taiping Rebellion Memorial Museum; in Nanjing it was the Yang-tze River Bridge and in Changsha we took them to see where Chairman Mao had gone swimming and where he had studied. But at night they weren't allowed to rest either. Regardless of whether they could understand a single word of it or not they were dragged off to watch a revolutionary model opera. If that proved completely incomprehensible, not to worry, the next day we'd whisk them off to watch revolutionary acrobatics—and there was no dialogue to worry about there. Even self-funded tourists got the same treatment. They couldn't just swan about enjoying scenery, visiting temples by day and resting at night. Just because you paid for your trip doesn't mean we weren't going to educate you. A Matter of StatusDuring this period we encountered numerous practical problems. For example, there was the issue of visitors engaging in activities incompatible with their status as tourists. This was a problem that we created for ourselves. Back then everyone in China regarded foreign journalists as devils incarnate: being on guard against foreign journalists was the same as preventing fires and guarding against thieves, it came naturally. But the more barriers you erected the more people wanted to take a peek and see what you were hiding behind that Bamboo Curtain. Journalists from all over the world had been trying every trick in the book to get into China, but neither the Ministry of Foreign Affairs nor the Association of Friendship with Foreign Countries would issue visas to them. They couldn't even get in as friends or relatives of diplomats based in Beijing. They had no way in. But journalists are journalists. Not surprisingly they discovered a few cracks in the Bamboo Curtain. One was the Guangzhou Trade Fair. Once journalists began pretending to be businessmen visiting the fair, that loophole was closed. The Trade Fair only issued visas to legitimate businessmen, and limited their activities strictly to Guangzhou. There was only one loophole left: the self-funded tourist group. They were supposedly on holiday: you couldn't keep out all the journalists who wanted to come to China for a vacation. So, some got in and engaged in activities incompatible with their status as tourists, causing no end of trouble. But it was hard to say which activities these were. Of course, if they snuck away from their group to interview people then they were no longer behaving like tourists; yet if they were just walking down the street like anyone else they'd naturally come across aspects of Chinese life that were backward or poor and, when they did, they'd photograph them like crazy. This in turn was seen as an unfriendly act, an example of poor behaviour and incompatible with their status as tourists. But what could you do about it? You could warn them or cut their trip short. You could even hand them over to Public Security and have them expelled. Foreigners were watched very carefully back then. We always knew if they were journalists posing as tourists and we knew how we were supposed to deal with them. Most of the time we just kept a fairly close eye on them. If they took too many inappropriate pictures we'd speak to them about it while trying not to make too big a deal about it, like a fart you let out discreetly. But in some cases we were told beforehand that if the person engaged in any inappropriate behaviour, whether it was taking too many pictures or phoning Beijing-based journalists with information, we were to notify our superiors immediately and the Public Security Bureau would deal with them. In these cases, the reasoning was that the journalist was known to have written articles attacking China, or to belong to a media organization which had an unfriendly attitude towards China. So CITS guides and tour leaders had to be politically reliable first and foremost— professional competence was only a secondary requirement. In the twenty years that I was a guide, from the 1950s to the end of the 70s, we kept such a close eye on travellers to China it was as though we thought they were going to steal something. We took them around by day and wrote up reports on them each night. If some individual seemed like they might present a problem we'd write it up. If nothing happened, fine, but if you hadn't reported your suspicions and something did go awry, there'd be all hell to pay. What am I talking about? For example, we considered it suspicious if any Chinese people came to visit them in the hotel. We considered it suspicious if a traveller snuck out to stroll the streets after everyone else had gone to sleep. Our judgment as to whether something was problematic depended too on how obsessed society was with class struggle at the time, whether the group was from a friendly country or an enemy state and whether the person in question was someone our superiors had told us to watch out for. China is a country with a long history and a vast territory. Its culture and scenery are rich and varied. Yet for the first thirty years of New China's history, and despite our wealth of natural tourism resources our travel industry was an awful, disorderly mess. And that was all because we treated tourism as part of our foreign policy and not a business. We'd struck out on the wrong path from the very beginning.  'Face the Future', by Chen Jiwu. First Prize, Fourth National Chinese New Year Pictures Competition. Source: Long Bow Archive The Huang Shan TalksIn July 1979, Deng Xiaoping had a three-day holiday at Huang Shan. Before he left he convened a roundtable discussion at which he made a speech that, after it was published, became known as the Huang Shan Talks. Those remarks put China on the path to develop a modern tourist industry. The centrepiece of Deng's observations was that the tourism industry had to be transformed so that it could become an overarching professional and economically viable enterprise. That was the kernel of Deng's thinking about the economics of tourism. He also remarked that Huang Shan had excellent potential as a tourist destination. It was, he observed, a place where we could make quite a lot of money. By speaking of tourism and money making in one breath he both corrected the errors of the past and finally gave business a respectable face. In that speech, he also touched on a whole range of details related to infrastructure. He said we needed to work on creating better conditions for tourism. He told us to improve transportation, accommodation and general services; hotel rooms had to be clean, sheets and pillowcases changed daily, and food should be prepared to suit the taste of foreigners. Staff should have at least a smattering of knowledge of foreign languages and tour guides needed to prepare proper itineraries. He even went into such detail as pointing out that the hotel there ought to have its own souvenir store selling trinkets and postcards of Huang Shan's scenery. … Deng did his sums too. He calculated that the average tourist spent US$1000 in China. If we had ten million tourists a year we could make US$10 billion, and even if it was only five million tourists we'd still be generating five billion dollars. He said, 'We must work to reach this figure by the end of the century.'… … Last year, 130,000,000 people visited China; they generated an income for us of US$419 billion. That's four times more than Xiaoping ever thought of. … … In the three decades before the Open Door and Reform Policies of 1978 CITS was like a series of patches on an overcoat—the overcoat of a uniform, of course. The patches covered up a few holes. Even though they were quite ugly they still cost a great deal. I myself was one of those patches, both before and after the reforms. When the Reform era started I was still quite young, but they didn't allow me to accompany tour groups. They made me a petty bureaucrat instead, gave me some administrative tasks, sat me in an office and put me to work on a history of tourism. So as a result I've just been a patch my whole life. But enough of feeling sorry for myself. At my age self-pity is in bad taste. Enough. |