|

||||||||||

|

FEATURESWu Zuguang: A Disaffected GentlemanWu Zuguang 吳祖光

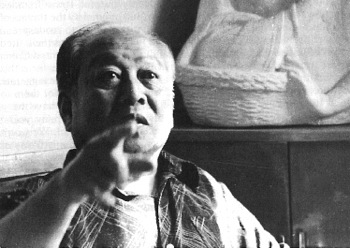

The playwright Wu Zuguang first paid for his outspokenness in the wake of the Hundred Flowers Campaign, a nationwide political movement during which Mao Zedong and the Communist Party encouraged people to speak out to 'help the Party' rectify its errors. Like tens of thousands of others Zuguang took up the call and, among other things, observed that Party leadership was not the key to a flourishing Chinese cultural scene. After all, he asked, did the famous Tang poets Li Bo and Du Fu have commissars looking over their shoulders? As the hundred flowers wilted Zuguang was silenced and in 1957, he was sent, again like so many others, to the Great Northern Wilderness to undergo a period of labour reform. Following the Cultural Revolution the authorities instituted a policy that encouraged leading writers, scientists and other members of the educated elite to join the ranks of the Communist Party itself. Zuguang joined up in 1980 (although his friend Yang Xianyi's application to join was rejected for reasons stated in the Editorial). Thereafter, Zuguang maintained his independence and became a vocal critic of the Party's erratic cultural policy. In 1983, while travelling in America, he went against Party discipline by criticizing the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign which was aimed at curbing dangerous liberalising tendencies in the society and, upon returning to China, organised a petition calling for a halt to such ideological purges. In 1986, he championed the cause of the banned play WM. He criticized the doctrinaire ideologues who called for this and other bans on cultural works, and berated them for being too spineless to admit openly that they had done so. All of this in the 1980s, an era of relative cultural efflorescence, one which enjoyed waves of 'bourgeois liberalisation' that allowed freedoms not enjoyed since 1949, and ones that have all too often been curtailed since 1989. In the spring of 2011, as China enters the centenary year of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 that supposedly saw the end of autarchy, it is timely to recall Wu Zuguang's comments on freedom of speech. The first of the two extracts below is taken from remarks Zuguang made at a meeting held in 1986 to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of Mao Zedong's 'Double Hundred' (or Hundred Flowers), policy speech. The second, 'Three Good Reasons for Quitting the Party', is from a letter addressed to the Central Advisory Committee of Communist Party Central. Immediately upon quitting the Party on 1 August 1987, Zuguang composed a different kind of letter: an invitation to friends to contribute to a collection he was planning called Essays on Dispelling Despondency (Jieyou Ji 解憂集) after the famous line by Cao Cao, 何以解憂,唯有杜康 (he yi jie you, wei you Dukang How does one dispel despondency? Wine, only wine), which features in the Editorial of this issue of China Heritage Quarterly. As we have noted in the Editorial, the inspiration for this collection, 'worrying about China' (to use Gloria Davies' formulation for youhuan 憂患) was soon reinforced by the fact that, after he was asked to quit the Party, Zuguang was inundated by letters of congratulation and support, as well as numerous gifts of all kinds of wine/jiu 酒 sent in celebration of his 'liberation'. In the introduction to the essay collection that appeared in September 1988 Zuguang praised Yang Xianyi as 'the greatest wine drinker of the age' (dangdai diyimingde jiujia 当代第一名的酒家); he noted that he himself had always been a teetotaller. The following passages are taken from Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, edited by Geremie Barmé and John Minford (2nd ed., New York: Hill & Wang, 1988), pp.368-72, with minor emendations. The Chinese-language sources are given below.—The Editor Cultural Assassins Fig.1 Wu Zuguang (Photograph: Mi Qiu 米丘) The crux of the matter is that it is all too common for people in power to say one thing but do another; or even do the exact opposite of what they've said. Then they get away scot free, regardless of how disastrous their actions may have proven to be. Ours is a land with thousands of years of feudal history behind it, where people habitually accept the right of might rather than the importance of democracy and law. The leaders and those they lead are often in a relationship of obvious inequality. Add to this the fact that over the last few decades it has been the 'fashion' to denounce and purge people. For example, just after the 'Double Hundred' Policy was announced [by Mao Zedong in 1956], encouraging intellectuals to make political statements and criticize the Party, a nationwide movement aimed at obliterating the very intellectuals who had done just that was launched, with the most frightening consequences. The number of people who suffered is incalculable, and this was but the first in a series of vile campaigns. There's a famous saying of the feudal philosopher Mencius: If a lord treats his ministers like dirt, then his ministers will regard him as 'bandit and enemy'. It shows that Mencius understood the relationship between the rulers and the ruled. Surprisingly even after all these years, there are many leaders who don't understand this simple principle. They treat the masses like dirt, see them as slaves and fools; at the same time they train a group of opportunistic flatterers vicious, double-faced rogues, as their intimates and strong-arm men: Decades of this situation have led to the near-extinction of integrity. The atmosphere of duplicity at one point brought New China to the verge of collapse, and it has still not been dispelled. From my experience, the aims of any level of feudal dictator [in the apparat] are completely incompatible with the aims of the so-called Double Hundred Policy. These dictators are like Qin Shihuang [the first emperor of China], they can't countenance any opposition within their sphere of control. They can only accept fawning and compliance. They appear stern and powerful on the surface, but in reality their every moment is spent in dread that they may lose their grasp on power. So it is inevitable that they feel threatened by anyone who does not agree with them entirely, worst of all the intellectuals, who think speak and write. Intellectuals have suffered like this for the past thirty years. Every political movement has been aimed at intellectuals first. The arts world in particular has been the first victim in every campaign. This is because intellectuals are not trusted… June 1986 Three Good Reasons for Quitting the Party

In 1987, when Wu Zuguang again called for an end to the Party's pervasive system of censorship, perhaps the most outrageous of his many acts, and derided the Anti-Bourgeois Liberalisation Campaign launched following the ouster of the Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang and the subsequent purge, the apparat called for action. Although Wu was on a second 'black list' drawn up after the expulsion of the controversial and independent-thinking astrophysicist Fang Lizhi, the writer Wang Ruowang and the journalist Liu Binyan from the Party in January 1987 during a nationwide attack on liberalism, nothing was done until later in the year. However, on 1 August 1987, the PolItburo member Hu Qiaomu was sent to visit Wu Zuguang at home. He read him a Central Committee document demanding that he resign his Party membership or face expulsion. Ten days later, Wu wrote 'A Letter to the Discipline Commission of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China' which he sent to Hong Kong for publication in September. In his letter he gave the reasons why he had relinquished his Party membership so readily.—The Editors of Seeds of Fire Although entirely unmoved by the criticisms of my 'errors' and dumbfounded by the extraordinary fashion in which I was requested to quit the Party-privately and without any scope for discussion—I acquiesced to Comrade [Hu] Qiaomu's request on the spot. I had three reasons for doing so: 1. Respect for the aged is a glorious Chinese national tradition. I have always treated my elders with respect. Comrade Qiaomu is a man rich in years and frail of health. To be the humble object of his magnanimous attention, indeed to be the cause of such exertion on his part—he had to climb up the four flights of stairs to reach my unworthy hovel—caused me the greatest unease. For this reason I said to Comrade Qiaomu: 'This decision has taken me completely by surprise, and I cannot understand it. But, as you have come here to present this request to me in person, I will accept it.' The Communist Party of China always had the magnanimity to accept criticism humbly. Only when all manner of ideas and the wisdom of the broad masses are accepted can the great task of reunifying China be achieved. I first came under the guidance of the Party in the 1940s, so I have had personal experience of this. 'When a gentleman is told of his faults he is delighted, when he hears of the goodness [of others] he pays them his respects'—this is one of the traditional strengths of the Chinese. However, starting in the late 1950s, some leaders in Party Central would only listen to pleasing words of praise, and became increasingly annoyed by criticism. For many years now, it is the most loyal and outspoken intellectuals who have been denounced, their lives destroyed. The numerous political movements have had an inestimable and devastating effect on a huge number of China's most outstanding talents. The results have been tragic. Although the Party has attempted to change, it is all too evident that up to now it hasn't been able to do so. August 1987

Wu's expulsion brought him sympathy from many quarters. He was invited to take part in the Twentieth Anniversary of the Iowa International Writers' Program in October, and during his trip to America remained critical of the Anti-Bourgelib Campaign. In one interview he commented: 'I know I can be a good human being, but it's impossible for me to be a good Party member too.' Sources:Extract 1: 吳祖光,《實現「雙百」方針有點希望了》,《九十年代月刊》,1987:9. Extract 2: 吳祖光,《至中紀委書》,《鏡報》1987:9. |