|

||||||||

|

EDITORIALNo. 16, December 2008The Heritage of Beijing WaterGuest Editor: Dai QingOur Guest Editor Dai Qing, the Beijing-based writer, historical investigative journalist and water activist, focuses on the aqueous heritage of China's capital city. Reflecting on the well-springs of the Olympic year and the bountiful supply of water during 2008, Dai Qing discusses the diminishing heritage of a resource that sustained the ancient city in the past, shaped much of its life, and determines its future. The Editorial features a map of Beijing Waterways and an important study, 'Beijing's Water Crisis, 1949-2008'. Both are in dowloadable PDF format. In this issue, we are supported by colleagues from Probe International (www.probeinternational.org), an independent think-tank and environmental protection group with which Dai Qing has worked closely over the years. We are particularly grateful to Patricia Adams, Executive Director of Probe, for permission to carry a selection of oral history interviews conducted by Wang Jian on the heritage of Beijing water. These accounts, which form the main body of Features in this issue, offer a plangent perspective on the city's vanishing heritage, they also add a dimension to earlier work that has appeared in China Heritage Quarterly on the Forbidden City, the Grand Canal and the Garden of Perfect Brightness. Two of these oral histories ('The Lost Rivers of the Forbidden City' and 'Vanishing Hai Dian') include interactive maps which, like the map of Beijing Waterways, were designed by Rachel Tennenhouse of Probe. In Articles we present a study of lesser-known Ming-dynasty imperial tombs by Eric Danielson. We also continue to pursue our interest in Princely Mansions and Invisible Beijing (see our earlier Issues 12 & 14 respectively) with the publication of the first part of an essay on the Hidden Mansion of Beijing by Sang Ye and the editor, which includes rare aerial photographs of the old city of Beijing. In New Scholarship, Claire Roberts introduces an important collection of Chinese art at the National Gallery in Prague and we have a review of May Holdsworth's compelling account of the rebuilding of the Garden of Established Happiness (Jianfu Gong) in the Forbidden City. We also present 'Chinese Visions: a Provocation' written by Gloria Davies, the editor and Timothy Cheek. An essay produced to frame a conference in August 2007, this 'Provocation'—in fact, an intellectual invitation—can be seen as being the basis for an ongoing conversation with Chinese academics and intellectuals regarding the various heritages of Chinese thought and how they may engagement with global discussions about the shared fate of humanity. This essay is a further addition to our articulation of New Sinology. As was the case for Issue 14 of China Heritage Quarterly (June 2008, 'Beijing, the Invisible City'), this issue is produced under the aegis of Geremie R. Barmé's 'Beijing as Spectacle' project which is supported by an Australian Research Council Federation Fellowship and The Australian National University. Other issues of China Heritage Quarterly related to the 'Beijing as Spectacle' project are: 'Yuanming Yuan, The Garden of Perfect Brightness' (Issue 8, December 2006) and 'Wangfu, the Princely Mansions of Beijing' (Issue 12, December 2007).

PDFs to download:

Beijing Waterways & Parks

Beijing's Water Crisis, 1949-2008

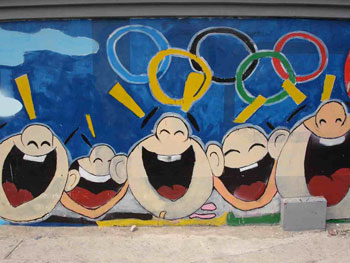

Beijing: an Aqueous HeritageDai QingEdited and translated by Geremie R. BarméMuddied Waters Fig. 1 Street-side botanic tableaux at the corner of the Lama Temple (Yonghe Gong) and the Second Ring Road, Beijing, August 2008. Photo: GRB.  Fig. 2 A floral ruyi auspicious sceptre, the Summer Palace, August 2008. Photo: GRB. In Beijing, the year 2008 was celebrated for the successful realisation of the 29th Olympiad. Although the propogandists made much of this being the realisation of century-long dream, in reality China has only really been in the throes of Olympic-mania from the start of this century, when intense efforts were made to secure and then stage the Beijing Olympics. It is during this same period, that is the last seven years, that the ancient Chinese city conintued to suffer from a devastating drought. Ironically, or not suprisingly given the nature of the official Chinese media, the precarious state of the city's water resources, and the imperilled heritage of Beijing's water, in no way detracted from the grandeur of the Olympics which were held in August 2008. During the weeks leading up to August, and for the whole Olympic month, the streets and intersections of the city boasted extravagant floral displays and all manner of horticultural tableaux on the theme of sport. Rich and verdant lawns filled the new Olympic Park, and at all the official venues and hotels there was an abundant supply of free-flowing water. Nor was there any faulting of the supposedly 'natural' river that provided the venue for the Shunyi Olympic Water Park outside Beijing itself. The Water Park was the site for the rowing and canoeing events, as well as the marathon swimming competition. (For more on this, see 'Thirst Dragon at the Olympics' in Features in this issue.) By the autumn and early-winter months of 2008, there was even some hint of natural water flowing once more in the long-dry riverbeds of greater Beijing.  Fig. 3 A horticultural dragon, Bei Hai Park, Beijing, August 2008. Photo: GRB. Although the once-proud rivers of Old Beijing have disappeared, the inhabitants of the city with access to the urban water supply suffer no obvious inconvenience. Be it cooking, flushing toilets, washing cars, watering lawns....clear and gushing water is always available with the simple turn of a tap. Things are not so carefree for the countless farmers who work beyond the Beijing conurbation, and toil on the land around the city's urban sprawl. The scarcity of water means that all too often the water pumps working the local wells can only be turned on once in the morning and again at night. And these are not the once shallow wells of the past, for they are now dug far deeper than they were even only ten short years ago. No longer do they tap into a watertable a mere ten or so metres underground, for they been sunk to a depth of one to three hundred metres. At least that is the case at Nongtai Village, an old community located on the banks of one of Beijing's most famous water sources, the Yongding River. Of this the public is blissfully unaware, and officialdom maintains an unflappable composure. The year 2008 was the first time in the twenty-first century that there was some hope that greater Beijing would enjoy annual rainfall over 600mm. With this came too the hope that the long years of drought were over and that things would return to 'normal'. Did the increase in water presage a return to regular flows of surface water, as well as the recovery of the whole water system of the capital district? If that was the case, one has to wonder how this 'recovery' was really achieved: Was it due to greater rainfall? Or because of the increase in trans-shipping of water from the surrounding provinces? Or were there other less evident sources of this natural bounty, such as more water pumped from aquifers?  Fig. 4 Olympic wall art at Qian Men, Beijing, August 2008. Photo: GRB. No one seems to be able to give a clear and direct answer. It is all but impossible to get any clear or definitive answers to these questions, whether it be from specialist research organizations, or from a system of government that claims to 'serve the people'. Be it the overall situation of water supply in China's capital, the amount of available water and its quality, or indeed the sources of the water being used, and future projections regarding sustainability—all things that impinge on the city's survival, all matters that residents have a right to know—belong to the realm of the unknown and the unknowable. Moreover, when Chinese and international journalists ask discomforting questions, the answer is always along the lines of: 'We're telling you there is no problem. There's no need for you to pursue the subject'. What's this all about? What is the relationship between this massive capital city and its water? And just why are the waters of Beijing so muddied?  Fig. 5 Chaoyang Park, Beijing, August 2008. Photo: Lois Conner. A Capital SourceUnlike many other great world cities and capitals, no major river courses its way through the city of Beijing. Nonetheless, over the three thousand years that there has been major significant habitation in the area of present-day Beijing (starting with the enfeoffment of Jiqiu in the area of what is today the Lotus Pond Park to the southwest of Beijing West Station in 1045 BCE) there has been water, and people, communities, kingdoms and dynasties have flourished because of it.  Fig. 6 Lawns and lights outside the Bird's Nest National Stadium, Olympic Park, Beijing, August 2008. Photo: GRB.  Fig. 7 Peking University, the South Gate festooned with Olympic decorations, August 2008. Photo: GRB. In 1151, the Jin dynasty established its central capital, Zhongdu, in the area of Beijing. Lotus River (Lianhua He) formed the life-giving arterial system of the city and the imperial demense which was located next to what is today West Beijing Train Station. Not far to the northeast of that city there was a network of lakes and waterways, which became the site of the Northern Palace, now the area of Bei Hai Park in central Beijing. Following the final conquest of the Jin rulers, in 1263 the victorious Mongols under Khublai Khan established one of the main cities of their Yuan dynasty in the defunct Jin central capital. While a major capital (Shangdu) was maintained at Kaiping far north of modern Beijing on the Luan River, Khublai also had an imperial residence on the prominent island in the lake palaces of the former dynasty—on what is known as Qiong Dao, or Hortensia Island, which is in modern Bei Hai Park. In those days, the lake around the island was known as the Taiye Lake and within a quarter of a century a new city arose around it, known as the southern Yuan capital of Dadu. The old Lotus River water system could no longer satisfy the needs of this expanded imperial centre. Where would the water come from now? Far to the northwest of the Yuan city in what we know as the Western Hills underground springs had turned the area into something of a waterworld (see 'Vanishing Hai Dian' in the Features section of this issue). A man by the name of Guo Shoujing (1231-1316)—an extraordinary 'proto-scientist' who with a talent for mathematics, astronomy and hydrology—identified the most best source of abundent clean water in the area at Yuquan Shan (literally, 'Jade Source Hill') and with the support of the court directed labourers to create a reservoir, Wengshan Bo (now known as Kunming Lake at the Summer Palace). He designed a water network that could supply water from the northwest of modern Beijing to the city through the Gaoliang He and Chang He rivers. Ebb and FlowThe waters from the northwest connected up to Jishui Tan (literally, 'Pool of Collected Water'). It became the main dock of the imperial city and was crowded with boats bringing goods and tribute from far flung places in the empire. This waterway was a crucial communications line for from the 1290s in the Yuan dynasty, through the Ming era and right up to the time that a modern railway was built to Beijing in the late-Qing dynasty in 1901.  Fig. 8 A bust of Guo Shoujing at a memorial hall dedicated to his memory. From the large body of water at Jishui Tan, Guo Shoujing's system connected to Taiye Lake (Bei Hai), the location of the Yuan imperial court in the city of Dadu, and also provided water for the Pipe River (Tongzi He), which would be the moat around the Forbidden City. This network was greatly expanded as part of the construction and expansion of the city of Beijing during the Yongle reign of the Ming dynasty in the early fourteenth century (for details see 'The Lost Rivers of the Forbidden City', in the Features section of this issue). By the late-Qing dynasty, the Chang He River had become virtually the exclusive preserve of the imperial court—used predominantly as a canal connecting Xizhi Men, the old northwest gate of the walled city, with the Summer Palace (Yihe Yuan) favoured by the Empress Dowager. It was, ironically, also used as a major transportation link by foreign forces when they invaded the celestial capital in 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion (in relation to this, and the fate of the pro-Boxer noble Prince Duan, see 'Prince Guo's Mansion' in 'Hidden Mansions: Beijing from the Air' in the Articles section of this issue). And since the founding of the People's Republic of China, Yuquan Shan itself, the source of Guo Shoujing's life-giving network of water, has been occupied by the Communist authorities as an army headquarters and as a site for secluded luxury villas for Party leaders and their families. |