|

||||||||||

|

T'IEN HSIAGems from the Mosquito PressDavid Chi-hsin Lu 盧褀新David Chi-hsin Lu was a journalist for the Central News Agency of China, and later for the Washington Post. His 'Gems from the Mosquito Press' was originally published in 1938. See T'ien Hsia Monthly, vol.VI, no.I (January, 1938): 7-17.—The Editor During the past 30 years there has been growing quite steadily a brand of journalism known as the 'mosquito' press. These small journals are made up chiefly of pseudo-news, semi-features and editorialised articles. Known as hsiao pao (小報), they have branched out into a distinct and specialized line of their own, quite different on the one hand from the big newspapers (大報), such as the Sin Wen Pao (新聞報), and on the other, from the tabloids, better known in China as hsiao hsing pao (小型報) – small size newspapers – such as the Lih Pao (立報).

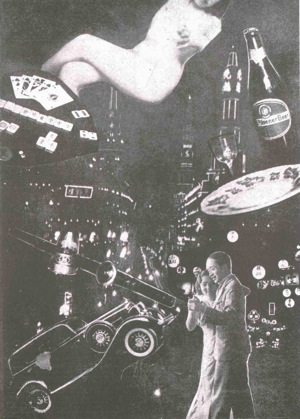

Fig.1 It is rather difficult to trace the origin of the term 'mosquito' (蚊) as applied to these small vernaculars; they have never been called such in the Chinese language. It is generally believed that the name was coined by some enterprising journalist to represent this special type of newspaper. Probably due to the fact that the mosquito is a small and trouble-making insect, and because some of its species transmit diseases such as yellow fever, the term was applied to these dwarfed sheets, which are generally known to be the purveyors of yellow journalism'. While the symptoms of yellow fever are 'fever, jaundice, gastro-intestinal disturbances and a state of prostration', yellow news in the hsiao bao comprises a mixture of things annoying, irritating, half-libellous and frequently biting and satirical.

Notwithstanding all the 'low brow' (下流) material printed in these papers, they have, nevertheless, won an increasingly wide circle of readers, and they are unique and welcome primarily because they are not, in the true sense of the word, news papers; they serve as a refreshing contrast to the bigger vernaculars which are usually staid and fully occupied with political and serious matters.

There is little detailed or official record of the history of the hsiao pao, but modern Chinese writers claim that this type of journalism started towards the end of the Ch'ing Dynasty. Unlike the Peking Gazette (京報), which dealt chiefly with political and court news, the hsiao pao steered away in another direction so as to escape the ever watchful eye of the censors. The muzzling restrictions prevalent at that time, it is claimed, served as the incentive for the 'mosquito' press to seek material dealing primarily with gossip from the theatres and amusement places.

In those early days quite a few of these little papers gained wide recognition. The

About twelve years ago these small journals began to flourish, particularly in the foreign controlled areas in Shanghai, but in a form slightly different from their forerunners. The reason for the sudden growth in their popularity was due to the fact that the general public were at this time disgusted with the corruption and oppression of the warlords and military satraps in various sections of the country. They were, moreover, 'fed up' with the political news published in the big papers which was generally depressing, and they consequently tried to forget their country's troubles by turning their interests to less serious matters. Petty newsmen and idle members of the literati class saw their opportunity of earning some easy money, and sexy stories and journalism of a deep yellow hue became the topic of the day. Led by the Fong Tang Shih Chieh (荒唐世界), a notoriously sexy journal, these papers fed the public with volumes of nonsense every day. This period has been aptly dubbed the 'scandal era' by some newspapermen, and during this time other 'mosquito' papers of the same type commenced and flourished.

Another reason why the hsiao pao thrived during this period was because many disgruntled and disappointed politicians either financed or actively edited such journals and used them as their own publicity organs, and these sheets served as a medium for such persons to attack their enemies, or as outlet to air their views and grievances. The small capital and outlay required made it comparatively easy for them to publish these journals, and thus if one expired another rapidly took its place.

This 'scandal era', however, was short-lived. The political change in the country in 1927-29 played a large part in improving the taste of readers who became tired of the indecent and sensational news diet. The public's interest shifted to politics, which was then of great importance due to the Nationalist Movement rapidly sweeping its influence northward from Canton. The Ying Pao (硬報) came into prominence and furnished the public with plenty of political news, but because it dared criticize public figures it was later ordered to close down.

The turning point for the 'mosquito' papers had, however, been reached, and the change in the temper of people started them on a definitely upgrade march. A remarkable change for the better has been taking place, particularly during the last five years. The economic depression and political crisis altered the outlook of editors and publishers, who began to see the handwriting on the wall. They also realized that the interest of the reading public had turned to the more serious side of life and that they must cater to this interest if they desired to continue to exist. Competition also made several of them attempt to improve their status. The financially weak and fundamentally unsound were weeded out and those which continue to be publishe today, including one which claims continuous publications since 1919 and a peak daily circulation of 50,000, have won a welcomed as well as a dreaded place in the country's journalistic field.

As has been already stated the Chinese 'mosquito' papers are not news papers in the strict sense of the word. They do not attempt to publish the daily chronological events of the world or of the locality in which they are circulated, which is the general practice of newspapers. They are in no way to be compared with the big journals either in size, bulk, contents, advertisements, or general lay out and organization. Most of them are founded with a few hundred dollars capital, and few, if any, have a printing press to their name, and unlike the big newspapers the hsiao pao do not subscribe to any foreign or domestic news services, nor do they engage a staff of reporters, sub-editors and make-up men who are indispensable in a modern newspaper office. While their big morning and evening contemporaries are read chiefly for the up-to-the-minute news from the four corners of the world, the hsiao pao are eagerly scanned for items of interesting information, gossip, tea-time chats and timely comments.

As a rile, the big newspapers are the chief source of news for the hsiao pao, but each of the latter has its own circle of key-hole reporters, anonymous contributors and paid writers, who are not only well-informed but are in most cases seasoned journalists – many being also employed by larger publications – and keen observers. The material published is not limited to China or to one locality, for one frequently finds 'correspondence' from as far as Tokyo, Berlin, Paris and New York.

But why read the hsiao pao when they depend on the big newspapers for news which has already been printed a day or two earlier? The answer is, people do not read them for last-minute news, but for extensive and surprising details as well as background information on the reports which have been previously published hurriedly and briefly in the more important dailies.

Much of their popularity also lies in their ability to seek the unusual; to avoid the straight, dull and staid reporting characteristic of the bigger newspapers. They present well-seasoned news and features with the purpose of providing entertainment and interesting reading. While the larger papers apparently attempt to publish news in an unbiased was and allow the readers to draw their own conclusions and make their own criticisms, the hsiao pao is radically different. Not only is practically every item of news and the features 'coloured' and opinionated, but every effort is made by the editors and contributors to touch up here and there, so as to make each story or article read attractively. This is probably the reason why the hsiao pao have become so popular and influential.

The more outstanding of this class of publication in Shanghai today are The Diamond (金鋼鑽), The Holmes News (福爾摩斯), The Great Crystal (大晶報), and Star Morning News (明星日報). These can all be classed a 'respectable', and they are widely read by educators, government officials, editors of big papers and prominent leaders in all walks of life.

A New York editor once admitted to the writer the undesirable effects of the American tabloids on their readers, who are chiefly from the so-called 'lower class'. He expressed the opinion, however, that these journals were serving as a kind of 'stepping stone' to the bigger and better press of the country and were therefore playing a significant part in educating the people to be newspaper-conscious.

Asked as to whether it would be best to suppress all tabloids, he answered: 'If the New York Daily News, which has over 2,500,000 daily circulation, were closed today, there would be that number of newspaper readers less in this country the next day. Certainly these readers would rather go without papers than be forced abruptly to read the big journals for which they are not yet prepared.'

The same argument would hold true of the Chinese 'mosquito' papers. They probably do not have the moral and uplifting effect which puritans would desire, but they undoubtedly serve as 'stepping stones' to the better journals. These 'mosquito' papers, in spite of their defects, have become a daily necessity for the so-called 'lower class' as much as the big journals have become a necessity to the millions of educated people throughout the land.

The 'mosquito' papers are noted for their 'nose for news' and like sensitive bloodhounds they keep their nostrils so close to the ground that they not only find the scent of their victims but literally collect much of the dust and dirt as well. Many trivial things, which are either missed or deliberately ignored by the big press, find prominent place in the small journals. It is quite obvious that a barber and a college professor are equally interested to know that Christian General Fong Yu-hsiang can swear and use profane language when he is highly indignant; or that Philosopher Hu Shih once had a pet duck which he had to sell because his wife objected to having the bird running around the home.

Despite their small size and limited organization, the scope of the 'mosquito' press has no boundary as to country, race or creed. Their comments and daily observations cover events and items of importance from the remotest parts of the world. In their nonchalant and pungent fashion, they ridicule, criticize and attack as they see fit, and because they have no 'special interest' they have been able to comment more freely on a wider variety of subjects than their bigger brothers.

The editorials are, as a general rule, exceptionally good and intelligently written. Comments on world problems are usually straight and simple, written in an understandable language welcomed by the masses.

During the past five years these journals have devoted much space to the subject of relations between China and Japan. They have always taken a unanimous and definite stand for the return of the invaded territory, and are unwilling to compromise. Since the Mukden Incident of 18th September, 1931, they have undoubtedly been more outspoken and consistently critical of Japan than any of their big contemporaries, and in spite of Japanese dislike and protests and government instructions against the expression of anti-Japanese sentiments, both verbally or in the written language, these little papers have never relented in their scathing attacks and ridicule of Japan and the Nipponese militarists. It is quite evident that their editorials have not been taken seriously, otherwise the amount of 'unfriendly' comments and cartoons published during the last five years, and even today, could easily have created a first-class Sino-Japanese 'incident'.

The honey-phrased editorials in some of the big journals urging Sino-Japanese rapprochement are generally considered merely 'eye-wash', but it is left to the 'mosquito' press to frankly call the promises of goodwill and friendship from Tokyo 'hot air'. Sato's overtures for improved relations were cautiously commented upon by the big newspapers, but once again the small journals came forward and flatly told Sato that the only way to restore friendship with China is to return Manchuria and East Hopei to her.

Perhaps not a single Chinese will fail to agree with the Holmes News suggestion that China must, after all, meet a knife with a knife and a gun with a gun, in dealing with Japan. And who would not support the advice of the Ching Pao to the Japanese Economic Mission that the Japanese smuggling activities I North China should cease before any economic agreement be formulated.

In discussing European affairs the 'mosquito' press rarely fails to bring the issues home and to find a moral lesson for Chines. For instance, the Holmes News stated that the Spanish insurgents are similar to the Mongol 'irregulars' – both being aided by alien foes – and contends that in spite of Tokyo's denial, it is quite probably that 3,000 Japanese volunteers may soon go to help the Spanish insurgents. It makes no bones about saying that Germany is helping the Spanish rebels and that Japan is backing the bandits in Chahar, and sarcastically suggests that after the Spanish was Germany may return the compliment to Japan by sending Germans volunteers to help eradicate the Reds in Manchukuo, Mongolia and East Hopei.

Abyssinia, a country and word practically unknown to the hsiao pao fraternity, received surprisingly wide comment during the Italian invasion. Italy's conquest of the black kingdom was aptly compared with Japan's invasion of Manchuria, and not many will disagree with the conclusion of the Star Daily News that weak nations will continue to be the victims of the stronger ones and that in order to preserve our nation we must depend on ourselves and be prepared ofr ward.

A comparison of the attitude of the big and small newspapers an the isis Theatre incident will undoubtedly enhance the reputation of the latter in the eyes of those who have often ignored them. While the big vernaculars remained mysteriously silent on the Italian sailors' attack on the theatre, the incident brought forth a chorus of scathing comment from the hsiao pao. This is what one of them said on that incident: 'Italy tried to prevent a film of another country from being shown in the territory of a friendly nation. It is like a motorist who injures a pedestrian but refuses to let another express sympathy for the victim. How can the Italians expect us to respect them?'

One of the most unique roles which the mosquito press has played has been that of outspoken critic of the big newspapers. Rarely have they failed to utilize an opportunity to publicly attack and ridicule the faults – which are many – of their bigger contemporaries. For instance, would gullible readers of the Sin Wen Pao [have] been aware that a certain article on Kweihua appearing in one issue of that paper was 'lifted' in its entirety from the Ta Kung Pao, had not the Ching Pao (晶報) disclosed the fact? Again, the Holmes News unceremoniously exposed the 'photographic scoop' claimed by certain foreign and Chinese journals concerning the Donald-Chang picture which was captioned: 'Taken during the negotiations at Sian.' The public would have been fooled had not this 'mosquito' paper reminded its reader of the horse-sense fact that Donald wore a summer suit in the 'historic picture', and concluded that 'the Australian wouldn't be wearing such light clothing during the sub-zero weather of mid-December.' It went even further and disclosed the fact that the 'negotiation' picture had been taken months before by a foreign newsreel company, which later proved to be 'The March of Time'.

Experienced newspaper reader will endorse the opinion of a 'mosquito' press editor who stated that newspapers should be read, but added that not everything printed should be considered true. He said that if one is gullible to the extent of swallowing all the stories and comments in the daily press, one had better not read any paper at all.

While certain Chinese journalists have found it lucrative to evade the censors and seek protection behind foreign-capitalized newspapers, the little journals have raised a cry against the increase of Chinese language newspapers in Shanghai under alien control. Such papers as the American-owned Hwa Mei Wan Pao (華美晚報) and the Italian-financed Ta Hu Wan Pao (大滬晚報) evoked sharp criticism from the hsiao pao fraternity, which described such a tendency as tantamount to 'selling our freedom of speech to foreigners'.

No one will contest the argument of one of these small papers that freedom of speech should be sought through legitimate channels and not through foreign protection. Traitors, it argued, will naturally sell their body and soul for money without any concern; but if editors seek protection behind foreign-owned publications they are ten times worse than traitors.

When a big newspaper scoops the 'mosquito' press it isn't news, but when the case is reversed then it is news. Such was the classic example of the birthday party given by the leading Chinese newspapers in Shanghai to Gen. Wu Te-chen at a restaurant not long ago. While all the host papers kept mysteriously silent for fully three days after the event, and enterprising hsiao pao, apparently ignoring the censors warnings, published the story about the big journals' party. And strangely enough, all the big papers came out with the story the next day – fully 24 house behind the 'mosquito' press.

The 'mosquito' papers are widely known for the amount of fascinating 'back-stage' information which they frequently publish to supplement the big news 'breaks' of the day. For instance, the whole world learned through the reports printed in the big journals that the Young Marshal was sentenced to imprisonment, pardoned and deprived of his civil rights within a single week, for his part in the Sian coup, but again it was the hsiao pao that gave some of the most interesting sidelights on the dramatic trial in Nanking. The Holmes News disclosed the information that when the Young Marshal walked into the courtroom on the day of the trial he had a pistol strapped to his belt, while four of his trusted personal bodyguards were posted outside. When Gen. Chu Pei-the (now decease) came into the courtroom and saw the Young Marshal armed he became very indignant and immediately ordered Chang to remove his pistol and demanded the withdrawal of the bodyguards before the trial began. These orders were complied with at once.

Other 'juicy' items which make up the contents of the hsiao pao and interest the public are report like the following:

Butterfly Wu getting a salary of $2,000 monthly, and being the highest paid movie actress in this country.

Miss Liang Sai-chen of the Liang cabaret sisters fame planning to retire when she has saved $300,000.

A one-time society beauty now living comfortable on $400,000 worth of property given to her by old play-boy friends.

Twenty cabaret girls in a certain dance hall getting married last year but ten of them returning to their jobs six months afterwards.

Miss Yeh Chuan-chuan, a taxi-dancer, buying a graveyard for her grandmother and mother, so that when they die they will not be without a burial place. Probably the most filial girl among the thousands of dancers in Shanghai. Many 'mosquito' press writers are day-dreamers and philosophers. Readers can frequently find passing remarks which, however inconsequential, nevertheless, provide much food for thought. Invariably such items come within the realm of the experience of ordinary folk and thus makes them more universal and popular [sic]. Many persons probably possess the same habit as one writer who admitted that whenever he had money he tried to buy something tangible and durable 'otherwise he would squander it on cabaret girls, shows and restaurants.' He explained that on one occasion he came into possession of a few dollars and immediately bought a leather brief case. An empty brief case was useless, he though, unless he had some writing paper in it. But alas! he didn't have any money. He went on to say that one night at a party he won a raffle prize which contained a package of the much-wanted writing paper. He philosophizes that if a person has good intentions he will eventually succeed.

Topics on love and romance are, of course, found in the small papers. Stories of a romance between a dancer and banker, and the daughter of an official and her father's chauffeur, often provide spicy items on the hsiao pao menu. However, the discussions on love are generally sane and clean.

No one will disagree with one hsiao pao editor who says that love like everything else changes with time. He compares love between man and woman to an elastic garter, which when new is strong and useful, but when old becomes weak, loose and useless. He cynically adds that love is also like a toy and woman like a child. The child loves the toy when new as if it were his very life, but when the toy is old it is put away and forgotten. This instinct of 'forgetting and putting away' comes with th child on the very day he is born.

The 'mosquito' press is continuing to improve and grow, and it is difficult to predict at this time to what heights it will eventually reach. The trend in Chinese journalism new seems to be towards the small press, including the hsiao hsing pao (小型報), which, with the exception of the Lih Pao (立報), has not been entirely satisfactory or successful from the financial and circulation stand-point. Many tabloids are trying to ape the 'mosquito' press features but still place their main emphasis on world and national news in skeletonised form.

One well-informed journalist is of the opinion that the 'mosquito' papers of the better type will continue to increase as such journals face fewer obstacles in comparison with the bigger newspapers and are, moreover profitable. With all their defects – and they are many – the hsiao pao have been firmly planted in China's Fourth Estate, and to all appearances, they have come to stay. |