|

||||||||||

|

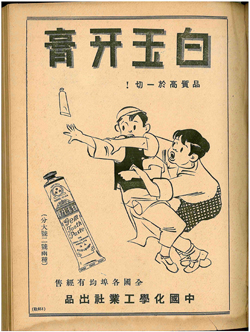

T'IEN HSIALibrary ChronicleV.L. Wong 黄維廉V.L. Wong 黄維廉, 'Library Chronicle', T'ien Hsia Monthly, Vol.VI, No.4, April 1938, pp.369-376.Though the history of libraries in China dates back to several thousand years ago, the rise of the modern library movement is of fairly recent origin. China's present Library Law has its origin in 1909 during the Manchu dynasty, when the Board of Education promulgated a set of twenty regulations governing the functioning of the National Library of Peking, then known as the Metropolitan Library, and all the provincial libraries.  An advertisement from Yuzhou Feng Magazine. Since the establishment of the Chinese Republic in 1912, the Chinese Library Law has been revised and promulgated three times. In 1915, the Ministry of Education promulgated a set of regulations on the promotion, organization, and administration of libraries throughout the different provinces of the country. In 1927, the University Council of the Nationalist Government at Nanking revised the then existing law, and in 1930, it was again revised by the present Ministry of Education, and the revised regulations are still in force today. Since the gradual disappearance of the old idea regarding the librarian as only a keeper of books, there has been a growing demand for trained librarians. Chinese librarians who had years of practical experience in administering libraries at home went to America to continue their studies in the new profession. Library schools in one form or another have been inaugurated to give courses in library science and administration. In this connection, nothing is so memorable in the history of the modern library movement in China as the work of the late Miss Mary Elizabeth Wood, a woman of great vision, who had long foreseen the need of modern libraries in China. As a missionary connected with Boone University at Wuchang, Miss Wood devoted part of her time to the work of developing the university library there. The first thing she did was the sending of two of her men, Samuel T.Y. Seng and Thomas C.S. Hu, to America for professional library training. Mr Seng went to America and entered the Library School of the New York Public Library in 1914, and he was followed by Mr Hu in 1917. The late Mr H.Y. Hsü, sometime librarian of St. John's University, Shanghai, went to the same institution in 1916, and in 1917 T.C. Tai went from Tsing Hua College, Peking, to the New York State Library School at Albany as the first Chinese student there. Thus unassumingly and quietly the movement was launched, and it was the beginning also of a group of Chinese students going to the United States especially for training in librarianship. Soon after their return to China, Mr Seng and Mr Hu of the Boone University library staff were connected with the Lecture Bureau of the National Committee of the Chinese Y.M.C.A. in Shanghai. Through the arrangements made possible by its Secretary, the late Dr. David Z.T. Yui, they were able to visit more than ten of China's important cities, giving demonstration lectures on the need for public libraries in China. Several important results grew out of these lectures in these great cities, but none was more important than the help in getting the way ready for a national movement for modern libraries. Under the direction of Miss Wood and her two American-trained Chinese librarians, a regular curriculum of library science was introduced at Boone University, Wuchang, in January, 1920—the first institution in China to have such a professional course. Since 1929, it has become a separate school on the undergraduate level, known as the Boone Library School, which still remains as the only library school in China. It offers a two years' course and admits students of junior standing. It is equivalent to about the first year work in an accredited American library school. Many of the young librarians now occupying important positions in libraries all over the country are graduates of the Boone Library School. The school is receiving annually a special grant for professorship and scholarships from the China Foundation for the Promotion of Education and Culture in charge of the Boxer Indemnity Fund. But the demand for trained librarians is larger than the Boone Library School can supply, hence library trustees and educators introduced apprentice courses of library science and also summer institutes in order to give the present library workers a general knowledge of library service. In the summer of 1920, in response to the requests of the librarians and the educational authorities of the various provinces, the first library summer school in China was opened at the Peking Government Teachers' College, now known as National Peiping Normal University, under the direction of Dr. T. C. Tai, then librarian of Tsing Hua. In spite of the troubled conditions in the country then, it was a great surprise to all that the enrolment numbered seventy-eight men and women, most of whom were librarians of various provincial libraries and were sent up to attend the summer school. Since then, summer institutes have been held every year in different parts of the country, always well attended. Library courses, varying from a few lectures to full semester courses, are also given at some of the colleges. The first formal library organization in China was the library section formed in 1921 under the auspices of the National Association for the Advancement of Education. At the time of their first annual conference held in July, 1922, at Tsinanfu, Shantung, the librarians of the principal educational institutions passed several resolutions regarding the administration of Chinese libraries. In 1923 when they met for the second time, they drew up another set of resolutions on the library, and the annual meetings continued through 1925. Under the stimulus and guidance of this annual sectional conference on libraries, many local library associations were formed in various cities. The crowning result of these associations was the formation of the Library Association of China in Peking, on June 2nd, 1925, on the occasion of Dr. Arthur E. Bostwick's mission to China as delegate of the American Library Association. The National Association now publishes a bi-monthly bulletin in Chinese as its official organ, and also issues a Chinese Library Science Quarterly, which is devoted to discussions on the promotion of the theory and practice of library work and the development of a library science adapted to the needs of China. Although the Chinese National Library Association was formed in 1925, the Association had not been able to hold an annual conference until January, 1929, when it was called to take place in the new capital of Nanking. The government gave its support to the meeting in the warm receptions extended to the delegates and financial support to the Conference, also an additional grant towards the organization of the Association. The conference was attended by 172 delegates representing 16 provinces. In August, 1933, the Association held its second annual conference at the National Tsing Hua University Library, Peiping. In spite of the hot weather, there was a good attendance. Among the many resolutions adopted, there was one emphasizing the need of introducing library courses into the curriculum of the national universities. The third annual conference of the Association was held in July, 1936, at the National Shantung University, Tsingtao. Some of the more important resolutions passed were directly related to the promotion of a better personnel and more adequate funds for the upkeep of libraries. At the A.L.A. Fiftieth Anniversary Conference held at Atlantic City, U.S.A., in October, 1926, China, as well as the National Library Association, was well represented by Dr. P. W. Kuo, then director of the China Institute in America, Miss Wood, Mr A.K. Chiu and Mr C.B. Kwei—the last two named were attending library schools in America at that time. In June, 1929, the Chinese Library Association also took part in the First International Library Congress held at Rome. A delegate was sent over in the person of Mr Seng of Boone, and fine exhibits of Chinese books were held. Aside from those already mentioned, the factors that helped to push forward the modern library movement in China are numerous and can be briefly treated here. One of the most important influences that has contributed much to the progress of the library movement in China has been the changed educational policy and the rapid spread of modern education. The popular education movement has made possible the spread of education among the masses. The great increase of educated people since 1911 and their thirst for new knowledge has created a new demand for more and better libraries. The rise of the Chinese literary renaissance has also accelerated the development of libraries in China. The visit to China since 1913 of a number of eminent scholars, like John Dewey, Bertrand Russell, Paul Monroe, Von Driesch, Rabindranath Tagore, and others, has, through their lectures and contact with the intellectual leaders and students, exerted much influence upon Chinese thought and life and has brought about changed methods of instruction in the changing system of education which has laid so much emphasis on the use of libraries as a laboratory of research study. The passing of a national law in 1916 requiring the deposit in the National Library at Peking of one copy of every book published and presented for registration in the Copyright Bureau of the Ministry of Interior has also helped the spread of libraries throughout the country. Another factor which has contributed to the development of modern libraries in China and has gradually planted in the minds of the reading public the intrinsic value of libraries to a nation is the advancement of a new literature—professional literature on libraries and library administration, either in the form of periodical articles, newspaper supplements, or published manuscripts by qualified persons who have either acquired their library knowledge from abroad or from active work in the field at home. The earliest publication on the subject was a manual of library economy translated from Japanese sources by the Popular Education Research Association, Peking, in 1917. It was then followed by many other such publications and magazine articles in the New Education Journal published by the National Association for the Advancement of Education, Nanking. The Commercial Press, Shanghai, the largest publishing house in China, has achieved much in putting forth a great deal of valuable literature on the subject. The Shanghai Library Association was also instrumental in publishing a series of booklets on library science which is similar to the A.L.A. Manuals of Library Economy. Library publicity in one form or another, especially library exhibits, is another important factor in bringing about the interest of the general public toward the establishment and development of libraries. Bulletin board information, mimeographed book-lists, printed historical accounts of libraries, and such like, are all means to an end. The occasional exhibits arranged by the individual libraries and those held under the auspices of the various library associations and publishing houses, displaying the value of libraries in the educational development of a nation, all have the same object of arousing general interest in the national library movement. To no small degree, the examples set by many generous donors who had either made gifts of money or gifts of books have been significant in the history of the library movement in China. On account of political and economic reasons, the development of libraries in China has not been very remarkable. But socially speaking, the people have begun to realize the importance of libraries. Funds to erect libraries have been donated by public-spirited persons, though these are few in number. The most important evidences of this new spirit are the gifts of Meng Fang Library at the National Southeastern University, Nanking, now known as the National Central University Library, the Mu Tsai Library at Nankai University, Tientsin, recently destroyed in the Sino-Japanese hostilities, the Hung Nien Library at Chinan University, Shanghai, and that of Mr Yeh Hung-ying's gift to the Jen Wen Library. Through the good offices of one of the alumni, Dr. T. V. Soong, ex-Minister of Finance, St. John's acquired for its University Library in 1933 from the Sheng family the private library of the late Sheng Kung Pao consisting of 66,607 volumes of valuable Chinese books. Dr. Soong has also promised to endow an appropriate fund for the erection of a proper building to house the new Chinese library. The three Soong sisters have jointly given a building to house the library of Ginling College, Nanking, the foremost girls' college in China at present. Internationally, we have the helping hand of the United States and the co-operation of many other countries. A few of the learned societies, scientific institutions, educational foundations, and many departments of the foreign governments have made generous contributions of valuable publications to some of the important libraries in China. It is surprising to find the enormous amount of exchange material being carried to and fro between the National Bureau of International Exchange at the National Central Library in Nanking and the Smithsonian International Exchange Service at Washington, D.C. The Low Library of St. John's University enjoys the special privilege of being the only depository library in Shanghai for the Carnegie Institution of Washington publications as well as those of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Dr. Bostwick's mission to China in 1925 as A.L.A. delegate and his presentation of the value of the educational power of the public library as it is administered today was in many ways a great factor in bringing about the immediate success of the movement. The return of the American Indemnity Fund to China, due largely to the untiring efforts of Miss Wood, has made it possible to establish more libraries and promote the work of the existing ones. The grant of the Sino-American Boxer Indemnity Fund Committee to support twenty-five scholarship students at the Boone Library School is an opportunity to many young men and women who have the ability to become future librarians but not the material means to make them future leaders in the library world in China. There are also increasing opportunities offered to Chinese librarians for more advanced training and study abroad in the field of librarianship. The National Library of Peiping has been able to make exchange arrangements with foreign libraries whereby members of its own staff may work and study abroad. Such exchange relations exist between the National Library of Peiping and the Chinese Library of Columbia University, the Library of Congress at Washington, D.C., the Preussiche Staatsbibliothek at Berlin, the Library of the University of Berlin, and the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris. With the fellowships now offered by the Rockefeller Foundation for foreign students to study library science in America, some of the Chinese librarians have another excellent opportunity for advanced study and training abroad. The Chinese International Library at Geneva, which came into existence about a couple of years ago, was a result of the resolution adopted by the Chinese Committee for International Intellectual Co-operation. The general purpose of the library is to promote a closer educational and cultural relationship between China and the world. The activities of the library will certainly not only have the important function for the dissemination of information concerning Chinese civilization, but will also undertake to bring to the world the idea of a Chinese library which has so long a history. According to statistics published by the Ministry of Education in 1936, there are altogether 4,041 libraries in the different special municipalities and provinces in China. The increase in the number of libraries in recent years is indeed rapid and surprising. According to investigations made by the Chinese Library Association in 1925, there were then only 502 libraries. Investigations made by the same Association showed that the number in 1928 had increased to 642; in 1931, the number had increased to 1,527. The statistics published by the Ministry of Education in 1933 showed that there were 2,935 libraries. Within a period of ten years, the number of libraries has grown to 4,041, which is more than eight times as many as in 1925. The increase in the number of libraries is certainly an indication of the progress made. In spite of the general conditions of success of libraries as described above, most of the libraries in China today are, as Dr. Bostwick has remarked, 'functioning somewhat as libraries in the United States were doing fifty years or more ago.' Compared with those of Europe and America, Chinese libraries are still in the initial stages of development. The constructive work from now on is not only along the line of adequate buildings and rich collections but also toward an efficient personnel to insure effective service. The administrative, technical, and educational duties involved in the work of a librarian are real problems in the Chinese library today, and all these require a personnel trained to perform them efficiently. The mission of the library is to preserve, disseminate, and further human knowledge. In order that the books may be used properly, there arise many administrative problems in connection with the development of libraries in China which should be solved in the days to come. There was a time when complete adoption of the Western system of library administration was thought advisable, but this is no longer found practical now. The task today is to painstakingly and thoughtfully work out systems of our own to fit the needs of our readers and books. Aside from having richer collections and more adequate buildings, the trend should be in the direction of providing more funds for the running and upkeep of libraries, a better personnel to handle the work, and ultimately of making the library not only a scientific laboratory of study but also a useful social institution. |