|

T'IEN HSIA

The Night New York's Chinese Went Out for Jews | China Heritage Quarterly

The Night New York's Chinese Went Out for Jews

How a 1903 Chinatown fundraiser for pogrom victims united two persecuted peoples

Scott D. Seligman

On a Spring evening in 1903 in New York's Chinatown, a long line snaked down Doyers Street from the Chinese Theater. The huge crowd hadn't gathered for one of the theater's traditional Chinese operas, however, and it included an unusually large number of Caucasians. That night, lower Manhattan played host to an improbable coming together of two immigrant communities: the Chinese and the Jews. They were queuing up for a Chinese-organized benefit performance for victims of the Kishinev pogrom, which, in three days of anti-Semitic rioting during Russian Easter the previous month, had killed 49, injured nearly 500 and left about 2,000 Jewish families homeless in the capital of the Russian province of Bessarabia. 'It was remarked again and again,' The New York Times reported of the performance, 'that it must be the first affair of its kind that had ever occurred in the world.'[1]

So many people showed up that the actors had to give three consecutive performances in the 500-seat auditorium to satisfy all comers. The play, chosen because it offered a sympathetic portrayal of oppressed people, was a Chinese-language drama entitled The 10 Lost Tribes. Its subject, however, was not the destruction of the kingdom of Israel in Biblical times, but rather the subjugation of the Chinese by the Manchus in the early years of the Ch'ing Dynasty.[2]

How had this unlikely event come to pass? Fairly or unfairly, the Chinese were not associated in the popular mind with charitable efforts outside their own community. Nor, despite living cheek-by-jowl with the burgeoning immigrant Jewish community on the Lower East Side, had they ever seemed to take much notice of them. Who were the people who had arranged this event, what were they trying to accomplish and what persuaded their compatriots in Chinatown – many barely able to scratch out a living of their own – to come to the aid of suffering Jews half a world away?

'Great Interest on the East Side'

When news of the massacre at Kishinev (today's Chisinau, Moldova) reached the United States on April 24, 1903, members of New York's Jewish community wasted little time springing into action.[3] They had good reason for alarm. Although such atrocities had been experienced by their Russian compatriots before, this was the first pogrom of the twentieth century, and it had occurred suddenly after many years of relative calm. A committee composed of the community's leading lights formed immediately and began a drive to collect relief funds. Chaired by financiers Emanuel Lehman and Arnold Kohn, it included businessmen J.B. Bloomingdale, Daniel Guggenheim, Louis Stern, Isidor Straus, Cyrus Sulzberger and Isaac Wallach; financiers Jacob Schiff and Isaac Seligman and attorney Louis Marshall, among many others.

As the facts surrounding the violence in Russia came to light, anger grew, and with it support for the relief effort. News reports recounted that rioters had been goaded into action by a local newspaper that had invoked the 'blood libel' and falsely blamed local Jews for the death of a young Christian man. Russian authorities had reportedly stood by and watched the riot without intervening, except that they did not permit the Jews to fight back. The incident provoked an immediate international outcry, and Count Alexander Loiewski Cassini, the Russian Ambassador in Washington, fanned the flames on May 18 when he issued a statement to the Associated Press that essentially blamed the Jews themselves for the attacks that had been carried out against them.[4]

By May 8, a nationwide appeal had raised $10,000 from donors in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Scranton. Locally, house-to-house solicitations were organized and benefit performances at Jewish theaters announced. One theater mounted an original play about Kishinev and pledged to donate half the proceeds of five performances to the relief effort. And New York's Jewish merchants were asked by the committee to contribute 2% of their gross receipts for one day.[5]

Outrage at the events in Kishinev was felt more broadly than just among America's Jews. Newspapers across the nation editorialized about it and preachers of all creeds condemned the violence in their sermons. Even President Theodore Roosevelt expressed his indignation publicly when he received a B'nai B'rith delegation the following month.[6] Most of the actual relief efforts, however, were organized by the Jewish community. It must therefore have seemed odd indeed when the New York Tribune reported on May 8 that a Chinese merchant named Joseph Singleton had offered to arrange a benefit performance for the Kishinev victims at the Chinese Theatre. As far as the Tribune knew, it was 'the first time the Chinese have expressed sympathy for the Jews' and it noted that 'their offer has aroused great interest on the East Side.'[7]

Four Unusual Chinese Men

Singleton was one of a quartet of Chinese who spearheaded the effort, and there was nothing ordinary about any of them. They were community leaders well known both inside and outside Chinatown. At a time when most Chinese were precluded from entering the United States and most of those already in America felt forced into a perpetual defensive crouch, these four were activists, with agendas for change and high public profiles.

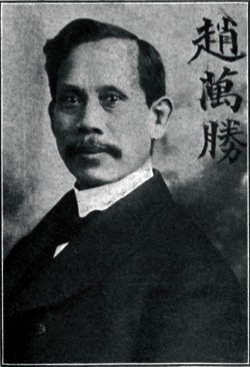

Fig.1 Joseph Singleton, or Chew Mon Sing ( Zhao Wansheng 趙萬勝). (Source: Warner M. Van Norden, Who's Who of the Chinese in New York, 1918, p.33)

The 49-year-old Singleton had arrived in New York 20 years earlier from Oakland, California, where he had done missionary work after emigrating from China in 1872. A Sunday school teacher and an interpreter for the Customs House, he had been known as Chew Mon Sing (pinyin: Zhao Wansheng) before he opted to take an entirely Anglo-sounding name – a very unusual act – in about 1887. He had also adopted Western dress and cut off his queue – the signature pigtail worn by his Chinese compatriots during this period and required by law in China. That same year, he wed the daughter of a prominent Caucasian member of his congregation who had been active in efforts to convert local Chinese. It had been one of the first such mixed marriages in New York, and the match had been a controversial one.[8]

Singleton was an activist with a history of reaching out beyond the borders of Chinatown, and he could boast many friendships with non-Chinese. In 1887—just five years after Congress had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, a xenophobic piece of legislation that effectively curtailed Chinese immigration to the United States for 10 years and rendered Chinese ineligible for citizenship—he had spearheaded a fund drive among the Chinese for a monument to Henry Ward Beecher, who had been a strong opponent of the bill.[9] Singleton had also worked for years to close down Chinese-run gambling establishments, earning the enmity of the tongs, the underworld organizations behind most of the vice in Chinatown. And in recent years he had gone into banking and cultivated many powerful people, among them government officials and business leaders sympathetic to the causes he supported, such as reform and modernization in his native land.

Closely allied with Singleton was Guy Maine, superintendent of the Chinese Guild at Manhattan's St. Bartholomew's Church, an Episcopalian organization he had helped found in 1889 to aid and protect the local Chinese population.[10] Born Yee Kai Man, the son of a Chinese missionary and a Bible teacher in Canton, he had come to America in about 1879. Like Singleton, he was associated with efforts to suppress gambling, and he had also helped establish a Chinese-language religious newspaper, The Chinese Evangelist.[11]

Maine had a ready command of English and had served as official interpreter for the Chinese government during the 1892 debate in America over renewal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which had extended the ban on Chinese immigration for a second decade.[12] He later became a court interpreter. Like Singleton, he had taken a Caucasian bride. Much of his work involved providing legal aid to Chinese victims of crime, who too often found it difficult to get law enforcement from the police or justice from the courts.

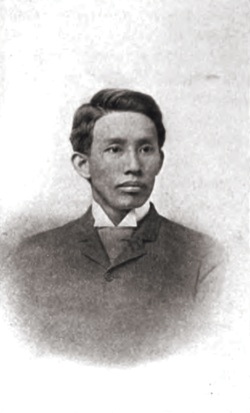

Fig.2 Dek Foon, more formally Ng Dek Foon ( Wu Jixun 伍積勳). (Source: Louis J. Beck, New York's Chinatown: An Historical Presentation of Its People and Places, 1898, p.270).

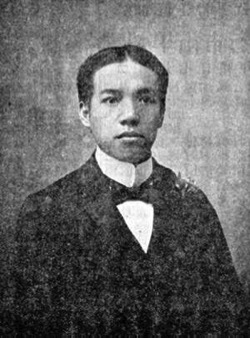

Fig.3 Jue Chue ( Zhao Zi 趙自), or Chu Sing Foon ( Zhao Chengxun 趙承勳). (Source: Chinese Exclusion Case Files, National Archives and Records Administration, Northeast Region, Box 47, Case 12, 165).

The other two men were Dek Foon and Jue Chue. Foon, who had come to America from China in 1885, had initially settled in California, and had come to New York by way of Nevada, where he had operated a laundry. In New York he found work as a traveling salesman, collector and bookkeeper, opened a restaurant, and eventually went into the advertising business. A devout Christian fluent in English, he, too, had chosen a Caucasian wife, and he was Singleton's partner in the banking firm the latter had opened in 1902.[13]

Finally, Jue Chue (pinyin: Zhao Zi) was a merchant whose Hing Lum Chan company, which dealt in Chinese and Japanese imports, was located adjacent to Doyers Street theater. He had arrived in 1899, leaving a wife and three children behind in China. Regarded as one of the wealthiest Chinese in the city, he was sometimes called 'The J. Pierpont Morgan of Chinatown.' In 1904, he and two others would bankroll a newspaper, The Chinese Reform News. And he would later lend his hand to efforts to make peace among warring factions in Chinatown.

These four men, who had known one another for many years, had much in common. All spoke English well, and all had opted to live their lives in America. They were men of some means, successful in their callings and deeply concerned with ridding Chinatown of vice and improving the lots of their compatriots, of whom there were as many as 7,000 in the New York area in 1900. Three of the four had married white women and at least three were converted Christians, which was true of only a small minority of Chinese in America. They had dispensed with their hair queues and robes and embraced Western dress. And like most Chinese, they strongly opposed U.S. laws that precluded additional Chinese immigration, made it nearly impossible for most Chinese in America to reunite with their family members unless they left the country, denied them citizenship and placed many other burdensome restrictions on them.

They also were all patriotic Chinese who believed deeply that their native land, then in the waning years of its dynastic system, desperately needed progressive reform. In this aspect they were followers of K'ang Yu-wei (Kang Youwei), a turn-of-the-century Chinese nationalist and political thinker who favored modernization and a transition to constitutional monarchy rather than violent revolution and wholesale overthrow of the ruling Manchus. K'ang had gotten the ear of the young Kwang Hsu (Guangxu) Emperor, whose 1898 'Hundred Days Reform' movement had been cut short by a coup d'état launched by his aunt, the reactionary Empress Dowager. The Emperor had been placed under house arrest and K'ang ordered executed, though he managed to save his head by escaping to Japan.

The Chinese Empire Reform Association

In 1899, K'ang, then in exile in Vancouver, founded an organization he called the Chinese Empire Reform Association, the overarching goal of which was the establishment of a constitutional government in China. In this effort he was ably assisted by Leung Kai Chew (Liang Qichao), a disciple and fellow Cantonese who, like him, had fled to Japan under threat of death, and who became vice president of the Association. Together they set out to create chapters of the organization wherever there were significant concentrations of Chinese.[14] Within the year, associations had been established in Boston, Seattle, Portland and San Francisco, but New York had initially proven problematic. Organizers were driven out of the city by the Chinese consul-general, who also threatened local merchants that support for such a group would hurt their business.[15]

By 1902, however, a New York chapter had finally been established, with Joseph Singleton as its head. Guy Maine and Dek Foon were also part of the effort. A banquet was held on November 18, 1902 to celebrate the milestone, and the guest list included several well-known Jewish figures, a number of officials affiliated with Tammany Hall, and a few, like Congressman Henry Goldfogle, who fell into both camps.[16]

It was in the name of this local chapter of the Reform Association that Singleton approached the Jewish relief committee with his offer of assistance for the Kishinev Jews. 'We want to help you. We believe in liberty and want to aid those who suffer from bigotry,' he told them.[17] And the vehicle he proposed was a benefit performance on Monday, May 11 at the Chinese Theatre, to be followed by a dinner at the 'Chinese Delmonico,' a well-known Chinatown eatery.

The Jewish group accepted the Chinese offer graciously, arrangements were made and word was spread. The appearance of throngs at the Chinese Theatre on the night of the show, however, was still something of a surprise. Although all performances were in Chinese, and although the popular impression of Chinese drama was that it was a 'strange, curious and grotesque mixture of barbaric costumes, wild contortions and horrible sounds,' incomprehensible to the uninitiated,[18] the theatre was nonetheless often visited by non-Chinese on tours of Chinatown.[19] The hall seems to have been readily available for special events such as this one, and was often pressed into service when out-of-town speakers of interest to the Chinese community passed through New York. It was, according to the New York Sun, the only facility for general public assembly in Chinatown.[20]

The 'Broad Platform of Americanism'

A total of 40 actors and crew members, all male, were associated with the theater, and they were usually compensated not with salary, but with a percentage of the gate. That evening, however, they donated their services. As in Chinese opera, the actors dressed in colorful costumes and all female parts were played by men. The drama starred Fow Chung, dubbed 'The Booth of Doyers Street' by the Tribune. He was said to have enjoyed a record number of curtain calls that evening.[21]

Fig.4 The 'Chinese Delmonico' Restaurant, Mon Lay Won ( Wan Li Yun 萬里雲), 24 Pell Street, Manhattan, in 1905. (From the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York).

There was no shortage of speakers. Guy Maine noted a strong bond of sympathy between the Jews and the Chinese, 'as both had been persecuted.' Rabbi Joseph Zeff, who spoke in Yiddish, also drew a comparison between the two peoples, focusing on Russian atrocities against both of them. Congressman Goldfogle, who represented New York's Lower East Side, had been on the agenda, but was not in attendance, so a 'Mr. Rosenthal'—probably Zionist leader and author Herman Rosenthal—spoke in his place, praising the Chinese organizers and expressing the indebtedness of the Jewish people to them. 'Let us extend a hand of welcome and hope that the Chinese may stand upon the broad platform of Americanism with us,' he said. It was a remark that could have been taken as a protest against the Chinese Exclusion Act, which the year before had been made permanent by Congress over the strenuous objections of the Chinese community – and those of many Jews, as well.[22]

Also on the program was Leung Kai Chew, the 30-year-old vice president of the Chinese Empire Reform Association.[23] Leung was in New York on his first visit to the U.S., ostensibly to learn more about America's institutions and its Chinese communities, but also to promote his organization and to raise funds. He had arrived from Canada two days earlier for a five-month lecture tour of 28 American cities that was to include a meeting with President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington. While Leung's presence in New York at the precise time of the Kishinev fundraiser can only have been a coincidence, his attendance at the event itself was anything but; it was his organization that had underwritten the evening's activities and, as it turned out, he took a special interest in the American Jewish community.

Leung's remarks do not survive, but the Jewish Daily Forward reported that he, too, drew a parallel between the Chinese and the Jewish experiences with the Russians. He called the Kishinev affair 'a recurrence of the wild slaughter of Chinese in Blagovestchensk,' a reference to the Russian occupation of Manchuria, and specifically to an atrocity committed by Cossacks in a town on the Amur River two years earlier in which the entire Chinese population of 5,000, including women and children, had been forced into the river and drowned.[24]

A Not-So-Kosher Banquet

After the benefit, which raised $280 for the Kishinev Jews, Singleton threw a banquet for some prominent New Yorkers at the Chinese Delmonico Restaurant. No ordinary chop suey joint, Delmonico's—Mon Lay Won (Wan Li Yun) in Chinese—was a handsomely decorated, somewhat upscale establishment at 24 Pell Street that catered to Chinese and non-Chinese diners alike and was known throughout the city. It had Chinese-style coffered ceilings adorned with lanterns, wooden arches richly carved with dragon motifs and Chinese paintings on its walls. Round tables inlaid with mother-of-pearl decorations filled the hall, and guests sat around them on wooden stools.[25]

�

Fig.5 Leung Kai Chew ( Liang Qichao 梁啟超). (Source: Tung Wah News, 17 April 1901).

Among the dinner guests that night was the famous Yiddish theatre actress Bertha Kalisch, who was appearing nearby. She and the other Jews present were apparently unfazed by the fact that Mon Lay Won, which featured pork and shrimp dishes prominently on its menu, was the antithesis of a kosher establishment. Exactly what was served that night is not recorded, but at a similar dinner Singleton had hosted there a few months before – also attended by several prominent Jews – pork and shellfish were notably absent from the table. That night, roast squab, chicken stuffed with reindeer ham, bamboo shoots and mushrooms and several varieties of fruit were served, although there was a course of shark's fin soup.[26] It appears that the Chinese hosts were trying, within their limited understanding of Jewish dietary laws, to make their Jewish guests as comfortable as they could, and that the Jews – at least some of whom surely were observant – were doing their best to meet the Chinese halfway.

The New York Times recorded that Singleton remarked to Kalisch at the dinner that the Chinese considered themselves as much persecuted as the Jews, and that there should be much sympathy between the two groups.[27]

Several months later, the Chinese Delmonico was again the scene of a banquet, but this time the occasion was the Jewish community honoring its four Chinese patrons. Singleton, Maine, Foon and Jue hosted the event, and each received an inscribed gold medal set with diamonds as a token of the esteem of New York's Jews. Tammany Hall figures and several other powerful New Yorkers were in attendance as well, as was 17-year-old K'ang Tang Back (Kang Tongbi), the daughter of K'ang Yu-wei. She had come to New York to enroll as a student at Barnard College, but was also promoting her father's organization. The previous month, she had presided over the inaugural meeting of its women's branch, the Chinese Empire Ladies Reform Association.[28]

Why the Jews?

Although there is no evidence that the display of Christian charity on the part of the Chinese organizers was rooted in any sense of spiritual or theological kinship with the Jewish people, there is little doubt that they had found common cause with Jews as victims of Russian persecution and cruelty. Certainly it was this obvious parallel that accounted for such broad participation in the effort on the part of the Chinatown rank-and-file. The theme was sounded again and again during the May 11 event by Jewish and Chinese speakers alike, and Leung Kai Chew went so far as to draw a specific comparison with Manchuria, which Russia was essentially occupying at the time. Nor was this commonality of interest wasted on the society at large, as a somewhat racist comment that appeared in several newspapers makes clear: 'As Shakespeare might have said,' the author observed sardonically, '"one touch of abuse makes the alien races kin."'[29]

But surely, in the minds of the organizers, there were other factors at work as well. First of all, even before the Kishinev event, these Chinese men had already begun reaching out beyond Chinatown to build relationships with members of the larger society. The November, 1902 banquet was not the only time they had entertained the rich and powerful. In mid-February, 1903, Singleton hosted another dinner to which members of the state Supreme Court, judges and justices of other courts and other VIPs were invited, many, again, with Tammany Hall connections.[30] The leaders of the Chinese community, which, unlike any other immigrant community, was disenfranchised by a law that denied them citizenship, were clearly in the process of building alliances to enhance their access to power. To the extent that Jews had already been successful at entering New York's power elite, this effort naturally included improving relationships with them.

Secondly, as targets of anti-immigrant prejudice themselves, Jews were obvious allies in the fight against exclusion. The Jewish press had opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act from the beginning, when it was first adopted in 1882. More recently, many Jews had spoken up during the debate preceding Congress' permanent extension of the measure in 1902. In late 1901, Max Kohler, former Assistant U.S. District Attorney in New York City and the son of a rabbi, wrote a blistering editorial in the New York Times condemning exclusion as 'the most un-American, inhuman, barbarous, oppressive system of procedure that can be encountered in any civilized land today.[31] And Simon Wolf of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations testified before a Senate committee that the law was unjust because it was discriminatory, and objectionable and unnecessary for a host of other reasons.[32] For the Jewish community, however, exclusion was not only a moral issue but also a pragmatic one, because what had been done to keep Chinese out could also be done to Jews, and if the pogroms continued, more Russian Jews would surely seek refuge in America. In fact, in the year following the Kishinev riot, Jewish immigration from Russia to the United States increased by more than 60% over the previous year.[33] In its coverage of the Chinese benefit performance, the Washington Times noted that 'The Jewish press of this country is loud in its protests against more stringent immigration laws for the United States when there are 5 million helpless Jews in Russia at the mercy of an uncivilized people. The only means of escape for their persecuted race they say is to emigrate, and if the doors are closed to them, how else will they find refuge?'[34]

The third factor that probably played a part in the decision to reach out to the Jews is made clear in the writings of Leung Kai Chew who, in addition to being a brilliant thinker, was also a diarist with a keen eye. Throughout his sojourn in America he kept a detailed account of his thoughts and observations, which he published upon his return to Japan as Notes from a Journey to the New Continent. Liang drew several comparisons between the American Jewish community, whose achievements he admired, and his Chinatown compatriots, whom he found wanting in many ways. He clearly thought the American Chinese had a lot to learn from the Jews.

'When I read the newspapers, I see that the Jews are the strongest among the immigrant communities in the U.S. I have heard that 30-40% of the banks belong to the Jews, and that 50-60% of the bankers and bank clerks are Jews,' he wrote in his journal, without revealing any sources for these ostensible facts. 'The longest street in New York City has thousands of shops. The Jews own 60-70% of them, while we Chinese have only one.'[35]

Leung also admired the fact that Jews had gained power in local government, in New York and elsewhere, and believed they had been able to accomplish all of this because they were united, a characteristic his factionalized Chinese brethren—in Chinatowns abroad as much as in China itself—sorely lacked:

The Jews lost their state thousands of years ago, but still remain united as a nation…The reason they are powerful is because of their strong national character. Where are the Babylonians and the Phoenicians today? Even the Greeks and the Romans are nowhere close to their ancient circumstances. We Chinese think we have a state. The second we leave it, however, foreigners treat us as far lower than the Jews. We fight and kill each other daily. Look at the Jews, they behave in precisely the opposite way![36]

There is no proof that these men had Leung's judgments about the Jews in mind when they decided to offer aid to the Kishinev victims, but it is likely they shared some of his opinions of their Jewish neighbors. And it is a safe bet that building bridges to the Jews appeared to them to be a good idea for more than the obvious reason of common cause against a single enemy.

Proximity and shared victimhood notwithstanding, however, an alliance between the two groups never really developed much beyond these efforts, and the event was probably forgotten before too long. But even if all it amounted to was a single night when one persecuted people reached out to another, it was no less an extraordinary—and quite unexpected—gesture of solidarity.

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes:

[1] 'Chinese Help for Jews,' New York Times, 12 May 1903.

[2] 'Chinamen in America are Mentally Broadening,' New York Tribune, 24 May 1903.

[3] 'Massacre of Jews in Russia,' New York Times, 24 Apr 1903.

[4]Cyrus Adler, The Voice of America on Kishinev (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1904), XII-XIII.

[5] 'Chinese to Aid Jewish Sufferers,' New York Tribune, 8 May 1903.

[6] 'President Hears the Case of the Jews,' New York Times, 16 Jun 1903.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Warner M. van Norden, Who's Who of the Chinese in New York (New York: s.n., 1918), 33

[9] The Beecher Monument,' Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 May 1887

[10] Arthur Bonner, Alas! What brought Thee Hither: The Chinese in New York, 1800-1950 (Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997) ,123.

[11] 'A Chinese Weekly Newspaper,' Hawaiian Gazette Supplement, 28 Feb 1888.

[12] 'Paramount Issues,' The Conservative, 2 Aug 1900.

[13] Louis J. Beck, New York's Chinatown: An Historical Presentation of Its People and Places (New York: Bohemia Publishing Company, 1898) 269-70

[14] Susie Lan Cassel, The Chinese in America: A History from Gold Mountain to the New Millennium (Lanham, MD: Alta Mira Press, 2002), 196-8.

[15] 'Off With Their Queues,' New York Tribune, 6 Aug 1901.

[16] 'Dinner Begins With a Dessert,' New York Tribune, 19 Nov 1902.

[17] 'Chinamen in America are Mentally Broadening,' New York Tribune, 24 May 1903.

[18] 'Chinese Drama a Serious Matter,' New York Sun, 12 Feb 1905.

[19] Daniel Ostrow and Mary Sham, Manhattan's Chinatown (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Press, 2008), 117.

[20] Chinese Drama a Serious Matter,' New York Sun, 12 Feb 1905.

[21] 'Chinamen in America are Mentally Broadening,' New York Tribune, 24 May 1903.

[22] 'Chinese Help for Jews,' New York Times, 12 May 1903.

[23] 'Chinese Play for Jews,' New York Tribune, 12 May 1905.

[24] 'Der Benefit in Khinezishen Teyater,' (The Benefit in the Chinese Theatre), Jewish Daily Forward, 12 May 1905. Translation courtesy of Alice Saitzeff Grossman.

[25] Rupert Hughes, The Real New York (New York: Smart Set Publishing Company, 1904), 157.

[26] 'Dinner Begins With a Dessert,' New York Tribune, 19 Nov 1902.

[27] Ibid.

[28] 'Gold Medals Given to Chinese By Jews,' Washington Times, 21 Nov 1903.

[29] Untitled, Canton (New York) Commercial Advertiser, 15 Jul 1903.

[30] 'Chinese Reformers Dine,' The Sun, 19 Feb 1903.

[31] 'Our Chinese Exclusion Laws: Should They be Modified or Repealed?' New York Times, 24 Nov 1901.

[32] Simon Wolf, The Presidents I Have Known from 1860-1918, (Washington: Press of Byron S. Adams, 1918), 287.

[33] Samuel Joseph, Jewish Immigration to the United States from 1881 to 1910 (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, 1914), 194.

[34] 'Hebrews Raise Money to Aid Kin in Russia,' Washington Times, 14 May 1903.

[35] Liang Qichao, Notes from a Journey to the New Continent [Xin Dalu Youji Jielu] (Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, 2007) , p. 47. Translation courtesy of Sasha Gong.

[36] Ibid., p. 48.

|