|

||||||||||

|

T'IEN HSIAThe Foreign Mentality in ChinaRandall GouldRandall Gould was the long-serving publisher and editor of the Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury. He was expelled from China by Wang Ching-wei's puppet government in 1940 for his strong anti-Japanese views. He returned after the end of the War to resume his role at the Post, finally leaving China in 1949. The following essay was published in T'ien Hsia Monthly, vol.VI, no.V (May 1938): 440-52.—The Editor Foreign thought on China has never before been in such a feverishly upset and generally fantastic state of confusion. Says the Latin: experiential docet stultos, experience teaches even fools; but for years, for centuries, the nations of the world have been buying experience in the Far East at high prices and from present indications they could assemble all they have learned on the head of a pin and have room enough left over to conduct a three-ringed circus.

That is, in fact, about what is happening. The spectacle of Shanghai alone must have the gods in stitches. With that as centre, and the fun spreading out to include diplomatic didos at such separated points as Nanking and Peiping, Hankow and Chungking, and with British Hongkong functioning now as cash-box and business-office of Chinese national resistance, we have political and economic complications spectacular enough for any circus bobbing up in all the world capitals whether of diplomacy or of the dollar, the pound sterling, the yen, the franc, the lira, the mark, the rouble and all the other quaint tokens through which we crudely and by ever-varying scales measure man's enslavement to or power over his fellow-man. Meanwhile to the accompaniment of a lot of very earnest shooting, bombing, burning, looting and rape, we have China and Japan enacting the historic role of the Kilkenny cats with China as unwilling host to the embroglio. In none of this do we have any indication that experience, civilization, Christianity, Buddhism, horse sense or Mr. Roosevelt's New Deal have had the slightest influence upon a turn of events based purely on the most brutal and blind resort to the law of tooth and claw.

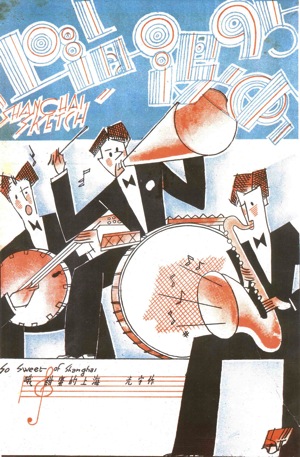

Fig.1 Japan has learned such lessons of the West as have suited her purpose and none could blame her for that had she displayed any intelligence and originality and power of sane selection. China, older and more shrewdly cynical, idled along making ancient ways suffice until belated realization of the approach of Armageddon caused her to strive for a modernization unfortunately specialized and inadequately achieved by the test of time. Meanwhile the Western world, uneasily conscious of a sense of at least partial responsibility, found its own time out of joint and its hydra-headed mind empty of anything constructive to say or any united way of getting together on saying it.

Some Oriental Henry L. Mencken should do a book on this. Standing on an ivory tower out of the direct line of fire, he could swing a bladder on a long string and whack intellectually bankrupt bald heads from Nome to Naples, from Moscow to Memphis, from Washington to Warsaw, from London to Lisbon. It would take a special acumen to attend to this job, but at least a modicum of literary skill and a good bit of general zest would be in order, naturally. I deeply regret that Dr. Lin Yutang, now immured among elderly English ladies and invalids at Menton on the Riviera, does not cast off his notions of a novel and tackle this politico-literary job with something of the same enthusiasm which he used to write of China's 'dog-meat General' and the laughing cynicism of a Tao philosophy now pretty thoroughly blown up by explosive gifts of the Japanese bombers. It would be rather Lin's dish of tea, I should say; but since he has temporarily erased himself from our scene and no other competent Chinese seems inclined to tackle the good work, I may at least sketchily indicate a few lines of thought regarding the criminal numbskullery of my own folk. If this be a traitor's role, make the most of it. I can only say that no small measure of self-confession enters into it.

Essentially we see a relation of the scatterbrained nature of the Western philosophies in our present mental decrepitude regarding China. We all thought we knew a great deal, but we actually didn't know about a large variety of things. We prided ourselves on our capitalism (or our triumphant march down the road toward communism), our political organization, our limitation of weapons of murder admittedly not yet forbidden nations as in the case of individuals but deemed offensive if not completely unrestrained (like the girl's baby which was illegitimate but 'only a little one'); we felt that peace was probably just around the corner, garages were going to be enlarged to take two cars apiece, every pot was to have a chicken in it and every Jack his Jill. These examples of over-optimistic thinking will be seen to be all out of date in varying degree, the garage-and-chicken idea for example being borrowed from the more pleasant days of the Hoover administration, and peace being a delusion of intermittent appearance like Haley's comet. I should say, offhand, that the most drastic wallops were dealt Western complacency by the World War and the world depression, but that the present state of affairs (if it is not over-complimentary to give it a term at least subtly implying some condition of organization still) may prove considerably more jarring than either. China is, of course, only one part of the scene and Europe may be a far worse mess for the world as a whole than anything China can cause. But China boils down, epitomizes, so much of the confused and selfish feeling that has been current in the world that perhaps in this instance the supposedly inscrutable Far East may be easier to read than a Europe too depressing for lengthy consideration by anybody but a masochist.

Let us ponder on Shanghai, that wonderful city raised to a greatness from a mud flat grudgingly accorded grasping foreign merchants by Chinese officials who didn't want them too close at hand. Most of the things formerly said of Shanghai were wrong at least in detail and I myself cannot plead 'not guilty' of confused and biased thinking, for a sojourn in Shanghai seems to have a bad effect on the brains. The climate tends to be too hot, too chilly, too damp, too conducive to mildew on one's wardrobe and mental furniture. However, we do the best we can and during periods of relative peace it is a cheerful job to perform such sanitary functions as endeavouring to scotch the old yarn that the Bund Gardens used to have a sign, 'No dogs or Chinese'. The trouble is that in another day the story was right in spirit if exaggerated in detail. After salutary lessons in 1925, 1927, and 1932, foreign Shanghai presented a brighter picture in Chinese eyes. Shanghai became really three cities – one French-controlled, one 'international', and a third enveloping city somewhat amorphous but unmistakeably Chinese. Here was a real chance for some constructive foreign leadership. Foreign areas in Shanghai were after all a part of China, and foreign thinkers realized that there was likely to be a gradual process of recession of foreign interest, retrocession of foreign control. Why not go the whole hog with a dash, both foreign authorities coming together on a joint plan for some such project as a Chinese Government-chartered united city in which there would be a truly international though still for some time foreign-led control? Quite possibly Chinese national feeling would have balked and the thing might have fallen through, but at any rate a tremendous impression of forward-looking impulse toward constructive leadership on the part of the foreign nations, and foreigners resident in Shanghai, would have been created on the Chinese public (and the world at large, perhaps).

There had been a drastic lesson in the 1932 hostilities. But the world has a painfully juvenile habit of loose thinking, and resort to such catch-phrases as 'lightning doesn't strike twice in the same place'. Chinese are as bad as foreigners in that respect, and probably more superstitious (if we except old-style Russians). Shanghai having had one war which was deemed the real thing, no one could believe that the 1932 argument might be put in the position of a mere curtain-raiser. Likewise the old habit of thinking that Shanghai was a great city, due to foreign enterprise and sagacity, died hard among both foreigners and Chinese. Both sides have displayed the greatest zeal in hanging on to such antiques as the Land Regulation of 1865 and a system of streets laid out mostly by the meandering of cows and creeks. Certainly Shanghai has some big buildings, and now Shanghai even has a telephone system that works, after years of affectionate clinging to the most obsolete of jingle-and-click boxes anywhere to be found on earth. But every improvement has been the result of individual enterprise, based on a canny expectation that the vast Chinese hinterland would pay for it; there has been no comprehensive planning, very little of anything fairly describable as public spirit, and many residents act as though they were roving around a jail, fitted with a vast number of quaint amenities at the disposal of those who have the wherewithal or at least a convincing exterior and the ability to sign their names. In other words the average Shanghailander is chiefly obsessed with spending as little time in the city as possible, as amusingly as the circumstances permit, and then departing for some more inviting spot whether it be New York, Paris, Little-Puddlemore-On-Tyne, or Ningpo-More-Far. This is not an atmosphere which makes for broad and generous thinking. The results are evident enough in the sad pass to which we are brought.

Nobody knows anything, today, of what Shanghai is to be made, unless we except the Japanese – and I for one refuse to except them because I think they merely have a fleeting power without knowledge. Japanese convey from time to time a convincing idea that they have a real programme for Shanghai (perhaps involving taking it over from hands which have proved so inept) but the fact is that they are not able to handle all that they have gotten involved in, and that their mental capacity is as sharply limited as their limited strength. So let no one count on the Japanese even for a firm hand, let alone a hand directed by intelligence superior to the intelligences which brought the present muddle of many drivers pulling the steering-wheel in different directions. Shanghai, founded on selfishness and trade, has still got the selfishness but the trade has at least momentarily departed. And the best present thinking appears recently to have been expressed by the American chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Council when he spoke against a proposal to do away with the two-lakhs-a-year Municipal Orchestra, saying that he had previously felt the orchestra might be dispensed with but now he felt that nothing should be let go; this at a time when virtually everything is being let go, more or less, but when the prevailing governing mores in Shanghai are on the Bourbon pattern and when with shut eyes and slippingly-clutched fingers the Americans and Europeans (Chinese being already pretty well out of the picture) are letting the Japanese yank away this thing, that thing, as unintelligently as the perquisites are held.

What, meanwhile, is the attitude of the learned home Governments? These seem to be lying on their respective backs and picking at the coverlets. In principle, none is willing to let anything be changed in Shanghai; and in practice, none is willing to do anything about it. The principle of grab-and-hold-on still holds true, of course, and some very firm 'no's' have been said against Japanese desires to take over the Shanghai Maritime Customs; but this will be done in due course, just as the Japanese-backed Ta Tao municipal government has got itself up on shaky legs and begun with real enthusiasm to collect taxes from such articles as are privileged to enter the foreign areas. It is all very amusing or am I wrong and is it merely sickening? – this utter planlessness of the Western world with regard to Shanghai, as with regard to so much else? One could respect bold intelligence defeated. But what are we to say when not even a dog barks? Certainly there is temptation to feel that Westerners jolly well get what they jolly well deserve, and to hell with them. But that, too, is unfortunately not very intelligent, so we must for very logic keep trying. However, let's on to a broader scene – China as a whole.

In my salad days in China, when Peiping was Peking but not yet the Japan-conferred Peking which is now due to have rivalry on the maps with the name Peiping still sturdily upheld from Hankow, foreign relations with Chines still retained at least the dignity of united action. We who sought to keep informed the minds of world readers were able to visualize things in the capital as between two parties – China and 'the rest', to borrow an English sports term. The Diplomatic Corps would meet (it was Peking's most refined though hardly liveliest club) and formulate a joint note to which all subscribed. That was sent to Waichiapou, which in turn would send back identic replies. True, a few cantankerous souls as Dr. C. T. Wang did not much take to this early demonstration of the United Front on the part of the foreign Powers, who were enabled thereby to enjoy a smugly contemplative attitude as they viewed backward China so unfortunately sunk in medievalism as compared with their modernized and prosperous selves. But there wasn't much to be done until Soviet Russia entered the picture and the late lamented and Stalin-liquidated Lev Mihailovich Karakhan, who would have been a remarkable man even without his black whiskers, not only became automatic Doyen of the Corps because of his unique ambassadorial status in the midst of ministers but also clearly demonstrated his complete unwillingness to play ball with the other boys. They hastily gave thought (in many cases, for the first time in years) and constituted themselves as an Assembly of Ministers or some such thing – the precise names now escapes me but the general idea was that while Mr. Karakhan might on ceremonial occasions head the full Diplomatic Body, when it came to club meetings he was not to be allowed to listen in on the little secrets of the elect. That was quite all right with Mr. Karakhan, who not only thereafter addressed his own separate notes to the Waichiapou but on occasion addressed acid communications to his fellow-inmates of the Legations Quarter, as for example when he demanded that the American Minister effect cessation of the Marine Guard's practice of riding horses disturbingly past the Soviet Embassy on the adjacent glacis. Mr. Karakhan lost that round, incidentally, as he fully expected to do – he had his quiet fun. It is too bad that the exigencies of preserving the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics did not permit of retaining Mr. Karakhan upon this uneasy sphere until he could learn of the recent dissolution of the U.S. Marine Mounted Unit.

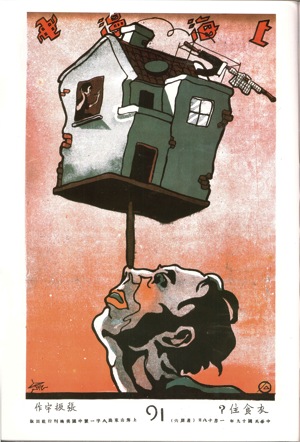

Fig.2 Of course the years 1926-27 brought the end of the world. This fact, naturally, did not penetrate the cloistered recesses of the Legation Quarter for some years more, but it became obvious that China's capital had moved to Nanking and that even the highest of foreign envoys must perform a tiresome journey there at least for the initial presentation of his credentials. The Old Guard hung on (in Peiping), however, and surrendered slowly, and one by one, under the sometimes rather irritated urging of home capitals which gradually became aware that it was no way to take tricks in China to have one's minister, or even ambassador, sitting in cool storage several hundred miles north of where things were going on.

During the last days of Chinese government at Peking, foreign unity on the matter of a 5 per cent maximum customs charge for China had broken down, and this was typical. Item by item, a Chinese governing group relatively compact (for China) and directed by the same sort of nationalistic penetration as is now manifest on the part of Japan, was busily knocking over this and that cherished and time-hallowed institution. Extraterritoriality tottered though it did not quite fall. I have heard that a Shanghai rendition agreement was actually framed and more or less agreed to in 1931. Foreign ranks were disorganized and being riddled by Chinese diplomatic shot and shell, though a dignified front was maintained and with a sort of drunken gravity the Powers agreed among themselves that rejuvenated China must naturally be given this, that, and other things – curiously enough, almost always the thing China demanded, which did not always imply it was the thing which developing circumstances might indicate China should have. It began to be as hard for a Chinese political refugee to find cover in the Shanghai foreign areas, for example, if the Chinese Government wanted to nail his hide on some nearby wall, as it is today for a Chinese patriot to find refuge there from the Japanese. The foreign motto was, is and no doubt will be, ' Divide and be conquered'.

Japan, meanwhile, not only had plenty of internal ferment but had other reasons for seeking a diversion in China. She viewed with alarm the ineptitude of her doddering Western neighbours. Particularly in Manchuria, she found Chinese 'progress' not to her liking. She had emulated the Russian liquidation plan in the case of the late unlamented Chang Tso-lin, only to find that while his son Chang Hsueh-liang lacked papa's incaution, he had instead a tendency to cling to his fellow-Chinese which had the natural result of strengthening Nanking influence in Manchuria and defacing the plain with Kuomintang flags. September, 1931, came; and nothing in all China was ever to be the same again.

It is useless and would only involve me in footless argument to embark on a rehash of such matters as Colonel Stimson's attitude on Manchuria and whether Britain did or did not let him (and China) down – as useless as it would be to jump forward to the present day and speculate as to whether Britain might (Mediterranean complications permitting) have done something currently if Uncle Samuel had not been so busy sucking his scorched fingers. Surely none can disagree with the unflattering thesis that foreign policies toward China have been uncalculated and almost universally inept; that here, almost more than anywhere else, Western civilization has failed to show itself what some few of us still idealistically feel that it could be.

Quite apart from any consideration of each friendly country desiring fair play for China, and being prepared to line up with all other friendly countries in forming a sort of lynch law delegation (if the thing had to be that crude) to assure Japan in measured terms that assault and battery were matters for the police court, there has been the most extraordinary ineptitude even in arranging how the gangs should choose up if they can't get together either to help or harm China.

In a recent article the American writer said that Britain's natural allies in the Far East against Japanese aggression are the French, the Dutch, the United States and Russia; her natural allies in Europe are the French, the Lowland countries, Scandinavia and Russia, with Italy a useful ally only 'as long as she has no grandiose imperialistic dreams.' Miss Thompson continues that the Japanese purpose is to challenge Great Britain, France, Holland and the United States in the Pacific. Actually it might be added that though Italy and Germany ally with Japanese against the Communist bogey, both of them (of course particularly Germany) have lost out in China trade because of the chaos produced by Japanese onslaught and it is very hard indeed even for Italian and Germans on the scene to figure out where they stand to gain, now or later, through Japan's imperialistic adventure however the thing may turn out from the Japanese point of view.

The United States, watching all this and likewise noting that, as Miss Thompson says, the Germans want to expand in the East at the expense of the small Central European States and Russia, while the Italians want to challenge France and Britain in the Mediterranean, and both have ideas about exploiting South America – watching all this squirming mess, the United States has a Garboesque desire to pack up and go home. The famous 'scuttle policy' clearly observable in Washington during the Shanghai fighting of last August, though rather successfully fought to a standstill by unexpectedly spirited Shanghai Americans, was nothing but a display of the old instinct to run back to Mother. As to American ideas of a Big Navy, although an occasional crackpot will bellow forth his desire for a navy big enough to fight victorious wars simultaneously in the Pacific and the Atlantic, the American people are actually supporting the notion of tremendous additional navy outlays simply because they are so sick and tired of all their neighbours. They want a naval Chinese Wall added to the obvious geographic barriers which Nature has put around them to shut them from contact with anyone but the amiable and 'Americanized' Canadians and the puzzling but after all inconsequential (except to the Rockefellers) Mexicans. In some ways they are smart in their very dumbness, for if they don't know what they want they at least have a fair idea of what they don't want, which is the rest of the world save on a trade – and that a cash-and-carry – basis, plus such culture as has been well dusted off and disinfected against microbes called Communism, Fascism and so on. American has at least one national crazy-house, located within the generous boundaries of Los Angeles, and there is no need in drawing on the rest of that world which Bernard Shaw once described as probable a lunatic asylum for the other planets.

It would be a tempting theme to run through the prevailing political psychologies, or psychoses, of some of the other leading nations: Of Britain, for example. Which is at least always loyal to herself, but which seems a little confused at the moment what with firing Mr. Anthony Eden, not being sure it was a good idea in view of subsequent events, and trying out Chamberlainean Pragmatism on Italy. Or of Russia, where everybody but Stalin is apparently more or less a traitor and they have shot so many people they had to start on the generals and won't that make everything great when the next Russo-Japanese war starts? But space limitations forbid dealing with anyone except Dai Nippon, the country that doesn't know where it is going but is well on its way, and even here it is useless to become involved in the endless ramifications of national thought and policy.

The one thing clear about Japan's policy in China is that nobody wanted or expected what has come to pass. Understanding that, we may perhaps exercise a little more charity for the confused state of thinking in this sufferer from an international inferiority-complex. Japan had grabbed Manchuria and got well away with the swag. Japan got Jehol and other adjacent areas to make Manchukuo look like the genuine article (which it was not, but why bring that up?). Japan finally decided that any sort of Shidehara kindness was wasted on China and that North China must be firmly seized along with Manchuria, thus providing needed raw materials, a rich additional market for Japanese goods, a firm base against Russia and a clear statement to the rest of the world that Pan-Asia was a fact with Japan at the throttle. But Nanking spilled the apple-cart and from August 13th, 1937, when the first shots of the second Shanghai war whistled into the headline, Japan was willy-nilly committed to an Alice in Blunderland role likely to prove as excruciatingly painful over the long haul as being ridden on a rail with nails in it.

If Japan suffers from divided counsels it is because a small boy has eaten too much and too varied an assortment of objects. The Japanese didn't want such a war, they wanted no war at all in fact (their persistent use of the word 'incident' is psychologically revealing). They didn't want the excitement to be protracted. They are in the position of a burglar who quietly crawls through a window, intending to make away with the family jewels and plate while everybody is asleep, and who finds himself stripped and being chased with paddles through a drunken house-party. All this publicity and punishment is very repugnant to Tokyo, but what to do? What is being done is to put a brave face on the matter and pretend that the whole thing, or most of the whole thing, is according to plan and in no major way disconcerting – due for a rapid and satisfactory finish if everyone will please look the other way and think about something else for a while. So the national resources are pulled together, unprecedentedly sweeping control and compulsion laws are put through as a measure of necessity, and Japan marches resolutely but blindfolded along the plank hoping that a stop can be made before the end is reached. It is probably very brave but certainly very idiotic, and probably in the long run (if the run is long enough) completely suicidal. But after all, suicide is so much the fashion that such a suicide-loving nation as Japan could hardly be a hold-out.

I say that suicide is the fashion and yet I rebel against that. The World War gave us enough grief. Capitalism has given us enough grief. Struggles toward other Leftist 'isms' have given us enough grief. How about a little fun?

Unfortunately, just as humour is the sign of the civilized man, so fun, for nations, cannot safely be had without more constructive planning than anything we have ever experienced. I do not speak of any Soviet Five Year Plan either; I mean a plan for all countries and for all eternity. It is hard to touch on such a topic without sounding like a combination of H. G. Wells and Simple Simon, but no idealist ever kept quiet because of fear of public jibes, the stake, or any other reason except that he was hungry and had his mouth full. So I say and I stick to it that sanity about the Far East is not impossible, and if pressed I could point at several sane individuals of mild character who could, if permitted, stop both the bloody onslaught and the international indecisiveness and work out a scheme fair to everybody. I have no idea that I shall be called upon to display my capacity as a picker. My only hope is that some few Far East observers of sound sense and seasoned experience may prove somewhere nearly as articulate as our visiting journalistic firemen and our out-of-date ex-residents who are now unfortunately remote from the facts of China, while maintaining a corresponding and at least equally unfortunate proximity to the publishing centre. Additionally I feel that the facts will gradually begin to speak for themselves, after they get bad enough. None is so blind as he who will not see, it is said; but there are signs – even such signs as the sudden upspringing of thoroughly intelligent group-discussion forums in the American Middle West are worth noting – that the people of the world want to see; that they are disgusted with dumb (in the slang sense) diplomats, and prepared to support diplomats of vision, who do actually exist despite the trails of politics.

This screed has been chiefly destructive, in a perhaps ill-tempered sort of way. I owe such readers as may have persisted through to the end a real apology if they have gotten nothing more out of it than an impression that years of Far East life have turned me into a China version of Donald Duck. When I cry out, it is with the hope that I may not only indicate the fire but call the firemen. We writing folk can do little but emit a loud noise, after all, and I have long noted that excitement is a good attention-getter. There has been too much sweetness and light about the Far East. We have heard for years about kindly effort on behalf of Open Doors, missionary endeavours and the sale of locomotives and machine-guns. I may perhaps be excused if I express rebellion against the loose-as-ashes thinking which has allowed the present cataclysm to start, and to continue. If no cures were possible it would be useless to cry out, but cures will be possible although this exact moment is not the time. Let us use this instant to experience a sense of shock at our own past feeble-noodleness and, summoning such mental resources as it has pleased an evidently penurious Deity to bestow, let us try in the future to be not merely careful but (for a change) to be right. |