|

||||||||||

|

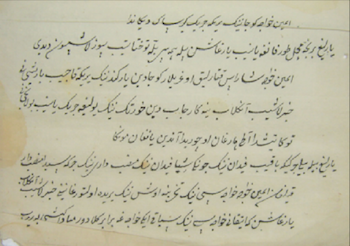

NEW SCHOLARSHIPXinjiang, 'Beyond the Problem'The Australian National University, 3-4 November 2011 A Workshop ReportSandrine Catris Indiana University BloomingtonThis two-day interdisciplinary workshop brought together scholars from Australia, Asia, Europe and North America whose work attempts to go beyond ethnic conflicts and Realpolitik approaches to thinking about Xinjiang's past, present and future. The workshop was jointly sponsored by the Australian Center on China in the World (CIW), the ANU Department of Political and Social Change, the ANU-IU Pan-Asia Institute, the Monash Asia Institute and the University of Tasmania.  Fig.1 Olympic Torch, Korla, Xinjiang. (Photograph: Tom Cliff, 2009) The workshop, which was organized by Tom Cliff (ANU) and Ayxem Eli (University of Tasmania), fostered lively interdisciplinary dialogue and debate. Although the papers varied greatly in terms of their temporal and disciplinary frames of reference, Cliff and Eli saw them as united by two themes: 'flows' and 'narratives'. They saw 'flows' as encompassing flows of linguistic space, of polities, of time, of peoples and identities, but also as flows between Xinjiang and outside of Xinjiang. The workshop began with opening remarks from Gardner Bovingdon (Indiana University Bloomington) via teleconference. Bovingdon underlined some important considerations for the future of research on Xinjiang. He began by recognizing the important work that has been done especially on geopolitics, the politics of identity, and trans-border flows up until now, but he highlighted the need for researchers to explore other avenues and move toward more theoretically informed scholarship. He urged scholars, including himself, to find balance in their work on Xinjiang and to avoid reducing the study of religion or literature, for example, to questions of political contention. He said that scholars have to avoid simplifying the situation in Xinjiang and need to recognize the variations in the attitudes of Han, Uyghurs and other minority groups. The papers from the first panel the theme of which was 'Qing History' offered complicating nuance to earlier theories about Qing-era rule in Xinjiang. In a paper entitled 'Yamen Uyghur: The Language of Loyalty in Qing Xinjiang', David Brophy (China in the World, ANU) challenged the hypothesis held by most scholars of the 'New Qing History' school, which posited that the Xinjiang Muslim population did not fit well into the Qing universalizing order because of the monotheistic nature of Islam. Using a linguistic approach Brophy suggested that the evidence did not warrant such a hypothesis and that in reality the Qing treated the Muslim elite in Xinjiang not as a distinct group but as a part of its Mongol constituency. He argued that 'at the time of the Qing conquest, Mongolian constituted a lingua franca linking the elites of Xinjiang, Mongolia and the Manchus, with a common vocabulary of rule.'  Fig.2 Turkic Translation of the biography of Emin Khoja, fol.8a. (Courtesy: David Brophy) Anthony Garnaut (Melbourne University) in 'Whose New Dominion? A Gansu perspective on the history of Xinjiang' applied William Skinner's macro regions system to demonstrate that Xinjiang was part of a larger region encompassing the upper reaches of the Yellow River, the Tarim and Turpan basins as well as Zhungaria. He argued that it makes more sense to analyze Xinjiang's history from the perspective of Gansu because of the strong political and cultural connections established between different Muslim groups from the macro region of 'Tunganistan'. His presentation highlighted the flows of people, ideas, commodities, and rebellions that have existed within this macro region. Laura Newby (University of Oxford) in her paper, 'Bondage on Qing China's north-western frontier', showed that the practice of bondage in Xinjiang during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did not discriminate between ethnic or religious groups. She defined bondage as relationships of power and powerlessness that confounded boundaries between colonizers and colonized, the oppressor and the oppressed. She showed how Chinese, as well as Muslims or even Europeans were forced into bondage in this region. Newby also outlined the multiple forms of bondage that co-existed in Xinjiang from the Qing conquest of Xinjiang to the fall of the dynasty in the early twentieth century, including indigenous and non-indigenous forms of bondage. Lewis Mayo (Melbourne University) served as panel discussant. He commented on the process of creating the modern Uyghur identity, and argued that it has been done on the back of the provincialization of Xinjiang. He reminded us that the creation of the nation is a process of 'mapping' and 'imagining'. In her guest presentation 'The Kashgar Project: Cultural Heritage and Job Creation?', Marika Vicziany (Monash Asia Institute) showed the diversity of the cultural heritage of Southern Xinjiang. She argued that by developing the tourist industry in Xinjiang, the Chinese government would not only be able to create jobs for local people but also find a way to finance the protection of the cultural heritage sites of the region. In the second panel, which was on education, Tim Grose, (Indiana University) and Chen Yangbin (La Trobe University) both discussed the Xinjiangban 新疆班 (the Xinjiang class), the boarding school programs for ethnic Uyghur senior-secondary students in schools located in Eastern China. In his paper 'Towards Another Minority Educational Elite Group in Xinjiang?', Chen argued that the group of young graduates from the Xinjiangban will form a new ethnic educational elite group in Xinjiang after they return. He contended that their experience in China proper makes them distinct from minkaohan (Uyghurs who test in Chinese in Xinjiang) and minkaomin (Uyghurs who test in Uyghur). Tim Grose's argument in 'The "Peacocks" are Leaving China's Northwest, and so are some Uyghurs' differs from Chen. Grose showed that many students from the Xinjiangban wish not to return to Xinjiang after graduating from high schools and universities in Eastern China. He argued that: 'Responses from Uyghur graduates of the Xinjiang Class suggests that these students have not been convinced that they belong to the Zhonghua minzu and, as part of this membership, must shoulder the responsibility of developing Xinjiang for the rest of China.' He saw their refusal to return despite encouragement from the China's Ministry of Education and Xinjiang's provincial-level government as a refusal to participate in China's nation-building project in Xinjiang. Andrew Kipnis (ANU) reminded us of the need to go to the problem before going beyond it. He commented that while it is important to recognize the diversity of Uyghur experiences or Han or any other non-Han nationality experiences, we cannot simply ignore the 'conflict' that does exist in Xinjiang. He also asked both panelists to think more about the issue of resistance, and whether refusal to return to Xinjiang or deviation from expectations by the state can always be seen as acts of resistance to the state. The third panel of the workshop addressed the issue of contemporary politics in Xinjiang. Michael Clarke (Griffith University) in 'Toward a New Geopolitics of Xinjiang? Negotiating between Outside-In and Inside-Out Perspectives' argued that the predominant geopolitical narratives are 'outside-in' approaches to Xinjiang that embed the Xinjiang 'problem' in broader discourses of international relations. Clarke suggested that scholars explore the possibility of 'inside-out' perspectives on Xinjiang as a way to get to a more nuanced understanding of this region. On a different note David O'Brien (University College Cork) in 'The Mountains are high and the Emperor is far away: How the misrule of Wang Lequan brought Uyghur and Han together' portrayed the misrule of Xinjiang by Xinjiang's Party Secretary Wang Lequan optimistically. Using interviews done during his fieldwork, he argued that Wang Lequan's corruption actually brought Uyghur and Han closer together, in a small way, as both groups celebrated Wang's removal from office. James Liebold (La Trobe) served as discussant on this panel. He commented that the emphasis on geopolitics is a reminder of the importance of spatiality. Xinjiang is indeed very distinct from other parts of China due to the many distinct lifestyles co-existing, such as nomadic, sedentary, rural, urban. He also commented on the important role rumors play in Xinjiang because the lack of access to reliable sources of information and the terrible consequences they may have. The fourth panel dealt with 'Social Histories'. In his presentation, 'Legends and aspirations of the oil elite', Tom Cliff investigated the ways that individual narratives are interwoven with the state/institutional narratives of the Tarim Oil Company and of the frontier. He argued that two legends emerged: 'a legend of hardship and sacrifice' and 'a legend of potential.' Cliff showed that, overall, these legends are concerned with the future and not the past. His research exposed the expectations and grievances of different micro-cohorts of workers within the oil company. The personal narratives he used illustrate the diversity of attitudes and beliefs of Han Chinese in Xinjiang.  Fig.3 Photo of one of the panels of the Korla mural from Tom Cliff's paper. (Photograph: Tom Cliff, 2009) In my own paper 'Wu Guang and elusive historical truths', I analyzed one man's memoir of the Cultural Revolution in Xinjiang. Wu Guang's memoir is that of a loyal party member. I attempted to demonstrate that although Wu Guang followed the official party line regarding the Cultural Revolution, he still portrayed his own experiences of suffering and confusion in ways that parallel other Cultural Revolution memoirs. I argued that Wang's personal narrative is an example of the ways that the state and people remember and forget the Cultural Revolution. Furthermore, I suggested that understanding the ways individuals, social groups, and states remember and forget historical events is as important as finding the elusive historical truths historians seek. The discussant, Jonathan Unger (ANU), commented on the use of narratives in both papers. Unger wondered if Wu Guang's confusion may be indicative of the irrationality of what happened to him rather than being a sign of intentional deceitfulness. He suggested that Cliff think about how the Tarim Oil Company fits in the scholarship on danwei and perhaps think of it as being a 'super danwei'. The fifth panel was focused on 'Identity'. In her paper, 'Turkestan Lovesongs, "New Flamenco" and the Emergence of the "World Citizen" in Urban Xinjiang', Joanne Smith-Finley (University of Newcastle) analyzed the ways that identity is represented, transmitted and contested in Xinjiang through lyrical texts and musical styles. She used the case studies of two singers: Arken, the Uyghur 'Guitar King' and Dao Lang, a Sichuanese immigrant to Urumqi who 'sold himself' as a Xinjiangren (a Xinjiang native). Dao Lang took inspiration from the music of the Dolan musical traditions and fused Han music with Uyghur music. In a way, Smith-Finley saw this as a parallel to the demographic fading of Uyghur identity. This Xinjiangren identity is an inalienable part of the Chinese nation. On the other hand, Arken fused Uyghur music with flamenco music to market himself as a Uyghur who is also a modern global citizen. The discussant Tamara Jacka (ANU) asked about the fan base of these two singers. She suggested that we think about the question of 'subaltern cosmopolitanism'. Some urban Uyghurs turn to Central Asia, Turkey, and the 'West' in order to redefine their identity as distinct from that of the Han.  Fig.4 Kulsan: From Sufi to Flamenco, 2009. (Photograph: from Joanne Finley's presentation) Ayxem Eli in her paper 'From Han to Uyghur: construction and dissolution of ethnic identity in Hami, Xinjiang (1880-1980s)' complicated even further the binary Han-Uyghur. Using personal narratives Eli argued that the waves of Han children who came to Hami in the nineteenth century to work as bond laborers became assimilated into local 'authentic' Uyghur culture. She demonstrated that while there is a stigma to being a descendent or one of these 'Han assimilated Uyghurs', called the Yengilars (the new ones) by 'authentic' Uyghurs of Hami, many of them assimilated and became successful 'Uyghur' community members and chose not to return to their original ethnic group. Jacka suggested that Eli theorize more about the ways that people challenge state categories of space, class, and nationality because the state's contemporary categories are not adequate to represent people's layered identities. In the final panel, Sugawara Jun (Tokyo University of Foreign Studies) and Joshua Freeman (Xinjiang Normal University) both explored martyrs and martyrdom in Uyghur culture. In 'Swollen Memory of "Martyrdom": Genesis and Development of the Legend of Abdurrahman Khan' Sugawara argued that unlike other heroes and martyrs of Uyghur literature, the story of Abdurrahman Khan's martyrdom has persisted to the present day because it is inspired by real historical events that happened in Khotan in the 1860s. He compared the different texts of this oral literature with other historical sources, and showed the ways in which local singers and local audiences 'fabricated' strong messages by either glorifying the hero's misfortune, or emphasizing his struggle against oppression. Finally, Joshua Freeman in 'Lutpulla Mutellip: Whose Martyrs?' questioned the ways in which the Uyghur national literary canon has been formed. Freeman asked how inclusive or exclusive are literary canon and how much are they in service of ideology, using the Uyghur poet Lutpulla Mutellip for his case study. Lutpulla Mutellip did not appear to deserve all of the admiration he received in Xinjiang. Freeman argued that it was because Lutpulla belonged to traditional networks but also revolutionary networks that he was able to receive patronage and be admired by a variety of constituencies and not necessarily because of his literary talent. Lutpulla, for example, could fuse communist and Uyghur identities and this made him palatable to the Chinese Communists in the 1950s. They lauded him as a communist martyr murdered by the Kuomindang. The discussant Justin Tighe (University of Melbourne) highlighted the complexity of the processes involved in the formation of memories about these two figures. He also commented on how memory can be manipulated for political or ideological reasons. Joanne Smith-Finley concluded the workshop by reminding us that it is often impossible for scholars to be in Xinjiang and not be touched by the 'problem'. She shared the concern voiced by Kipnis and reiterated that before moving beyond 'the problem', we need to approach it and acknowledge it. She urged scholars to question the Han/Uyghur dichotomy and to explore the multiple layers of identity within the world of Xinjiang. She shared some ideas about work that still needs to be done in Xinjiang Studies. For instance, she called for scholars to do work on the relationship between first generation Han migrants to the Xinjiang countryside and recent Han migrants. These first generation migrants challenge state categories as many of them speak unaccented Uyghur, gave up pork and converted to Islam. They do not fit neatly into the Han/Uyghur dichotomy. Smith-Finley reminded us of the importance of local dynamics and transnational processes in a world where territoriality is under siege. Workshop participants hope that in the future such a workshop will be held in China and include specialists based both inside and outside the People's Republic.

|