|

||||||||||

|

NEW SCHOLARSHIPChinese Garden Research in the Twenty-first Century: Ways and Field of ResearchA Report from the 37th Association of Art Historians Annual Conference University of Warwick, United Kingdom, 31 March-2 April 2011Winnie Y.L. Chan, University of Oxford Antonio Jose Mezcua Lopez, Granada University, Spain

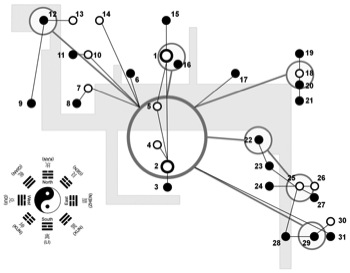

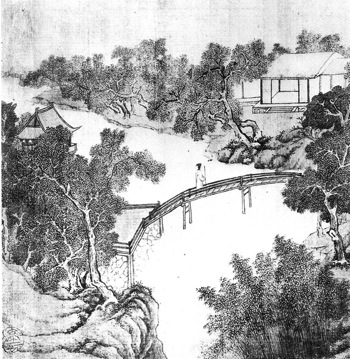

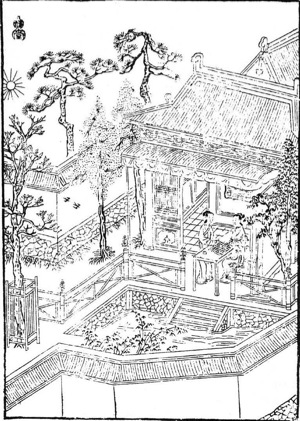

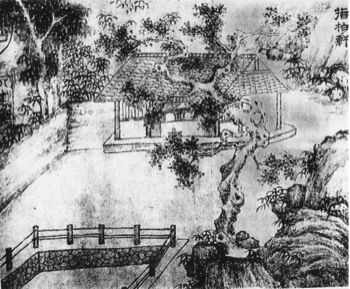

Winnie Y.L. Chan 陳婉麗 is a doctoral student in Chinese Studies at the University of Oxford. She worked as researcher in the Centre for Architecture Heritage Research, School of Architecture, Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her thesis topic is 'Merchants and the Remaking of Garden Culture in Qing China'. Antonio Jose Mezcua Lopez obtained his doctorate from Granada University in 2007 and the title of his thesis was 'Hermeneutic of Landscape in China'. His research interests mainly focus on the Song Dynasty landscape culture.  Fig.1 A conceptual diagram by Lu Andong of the central sites of Wen Zhengming's Zhuozheng Yuan The session 'Chinese Garden Research in the 21st Century: Ways and Field of Research' was held at the University of Warwick, UK, on 1 April 2011, as part of the 37th Association of Art Historians Annual Conference.[1] The conference with thirty-three sessions featuring over 270 speakers was organized by the Association of Art Historians and Louise Bourdua of the Department of History of Art, University of Warwick. The panel on Chinese garden research was convened by Winnie Y.L. Chan (University of Oxford) and the three papers presented at this session were given by scholars from institutions in China and Europe who are working in the fields of art history, architecture and landscape studies of China. Earlier studies on Chinese gardens had mostly addressed the topic through two interpretative paradigms: that of art connoisseurship (in which the garden is treated as an object of art), and that of the reductionist (in which the garden is taken as an unchanging generic category). Recent studies have essayed a more multidisciplinary approach, which places gardens into a broader and more nuanced context. It was this third approach, that of the social-historical paradigm, which was favored by all three speakers at this panel. The social/asocial role of gardens was exemplified in the first paper, that by Andong Lu 魯安東 (University of Cambridge) entitled 'Deciphering the Reclusive Landscape: A Spatial Analysis of the Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician in Wen Zhengming's 1533 Album'. Lu addressed how a retired official of the Ming period (1368-1644) used his garden to express his disconnection from politics. With his specialization in the narrative organization of space and the cinematic-aided study of architecture and urbanism, in his paper Lu used as his creative point of departure the spatial clues of gardens evinced in paintings of the time, adding to this an analysis of related prose and poetry.[2]  Fig.2 'Little flying rainbow' from Wen Zhengming's album of Zhouzheng Yuan images and poems Lu also introduced his current research work which is based on comparative studies of Chinese and English gardens. In the case of The Garden of the Humble Administrator (Zhuozheng Yuan 拙政園) in Suzhou, Lu demonstrated that a radical change in the concept of gardens occurred in the mid-Ming period, a time when gardens changed from being focused on productive farming to becoming objects of and places for aesthetic pursuits. During this transition, new aesthetic trends emphasized an articulation of nature that was part of a pursuit of aesthetic and philosophical ideals. These ideas drew on the earlier work by Craig Clunas who first suggested this approach in his 1996 book Fruitful Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China.[3]  Fig.3 Bodhisattva, Yuan dynasty, from the carvings at Feilai Feng Peak. Photo: Antonio Mezcua López, August 2010  Fig.4 Amitabha Buddha with 'strange rocks', Yuan dynasty, at Feilai Feng Peak. Photo: Antonio Mezcua López, August 2010 The presenter discussed in particular the figures Wang Xianchen 王獻臣 and Wen Zhengming 文徵明, who were involved in creating the physical and the visual realms respectively. He emphasized the particular historical context of these figures at a time when official careers were treacherous, advancement uncertain and the political climate unpredictable. Lu argued that these factors contributed to creating an environment in which garden spaces gave expression to ideas related to seclusion and oblique critiques of the politics of the day. Wen Zhengming in particular produced an album of thirty-one paintings with parallel poems about the garden which provide information about the mental and the physical garden spaces. The paintings served as a kind of imaginary itinerary that guided the viewer around the garden site from various semi-topographical standpoints. The views of the gardens, however, placed little emphasis on the connections between the various sites, yet the poems complemented the pictorial views and opened a field of sensations and feelings through the evocation of place and the use of literary allusions. The poems are prefaced with short prose prologues that suggest the locations within the garden and how they relate to the overall structure of the garden. If Andong Lu led us through a garden spaces using as his tools aesthetic theory and its historical implications, Gu Kai 顧凱 of Zhejiang University offered participants an excellent historical overview of the stylistic changes which gardens of the Ming period underwent in his paper 'Tradition and Transition of the Square Pond in Chinese Garden History'. Based on his recent book Gardens of Jiangnan in the Ming (Mingdai Jiangnan yuanlin yanjiu 明代江南園林研究, 2010), Gu Kai's paper focused on one particular aspect of Chinese gardens: ponds. Whereas it is regarded as being so axiomatic as to be treated as a dogma by scholars that the norm in Chinese gardens was ponds with serpentine banks, Gu argued that researchers have overlooked the fact that the square pond has also been widespread throughout the history of garden design. He illustrated his talk with details from the writings of Wang Shizheng 王世貞 and visual images drawn from Ming art that demonstrated how, prior to the advent of the new Ming garden makers, square ponds were a common garden feature. Through references to earlier texts by Bai Juyi 白居易, Sima Guang 司馬光 and Zhu Xi 朱熹 of the Tang and the Song eras (960-1279) Gu Kai demonstrated how square ponds featured in pre-Ming times. He further suggested that works such as Ji Cheng's 計成 famous The Craft of Gardens (Yuan Ye 園冶) and garden designers like Zhang Nanyuan 張南垣 of the seventeenth century had a crucial influence on the shifting of the style of gardens in the Ming, a time during which square ponds fell out of fashion. Gu remarked that the changes in garden design during the seventeenth century were not limited to the treatment of water but also had an impact on the use of rocks and indeed the entire conceptualization of garden structure. Although Gu Kai pointed out that the square pond was condemned by a new aesthetic, this garden feature was never banished entirely from the Jiangnan area as we can see from such extant gardens as Xu Wei's 徐渭 Studio of the Green Vines (Qingteng Shuwu 青藤書屋) in Shaoxing 紹興. Thus, in his paper, Gu Kai presented an argument that mitigated against reductionist views of the Chinese garden. Far from being an unchanging cultural form, the Chinese garden is in fact a dynamic space reflecting changes in tastes and styles over time.  Fig.5 A square pond. Source: 汪氏編, 宋詞畫譜, Ming dynasty A strange case in Chinese landscape history was explored by Antonio Jose Mezcua Lopez in which the tradition of Buddhist sculpture encounters 'strange rock' (qishi 奇石) design. In his paper, 'Feilai Feng Hill: A Fusion Between Buddhist Sculpture and Strange Rocks', Lopez traced the genealogy of the two traditions from the Five Dynasties (907-960) through to the Qing (1644-1911) in an attempt to uncover the textual and pictorial sources related to the Peak Flown from Afar (Feilai Feng 飛來峰) of Linyi Si Temple 靈隱寺 in Hangzhou, a Buddhist monastic site. The nature of sources provided interesting support for an argument that can be projected back to the socio-political and religious climate prevailing particularly during the Mongol Yuan era (1271-1368), one whose effects were felt in subsequent periods. Since it first featured in history, representations of Feilai Feng Hill have emphasized rocks and caves. During the Tang, Cold Spring Creek (Lengquan Xi 冷泉溪) was dredged and a pavilion was built on its shore. Thereafter, the fame of the site was evident from a court painting and poem by the Emperor Xiaozong 孝宗 (1162-1189) of the Southern Song. It features a piece of strange rock that once stood in the imperial garden of the Deshou Gong Palace 德壽宮 which is said to be 'the peak [that has] flown from afar'.  Fig.6 A square pond, from a painting of the Lion's Garden (Shizi Lin 獅子林) by Xu Ben 徐賁 For various personal and visa-related reasons three other presentations planned for this session were not delivered. The missing papers were Lei Xue (College of William and Mary, USA) 'Recycling the Antique Origin of the "Calligraphic Corridor" in Chinese Gardens' which discussed the recycling and display of calligraphic stones for printing 'model letters' (fatie 法帖), an architectural element in the construction of 'calligraphic corridors' (beilang 碑廊) in eighteenth-century gardens. In her paper 'Site of Art Exchanges, Social Contacts and Conflicts: The Chinese Hong Merchant Gardens of Canton, 1685-1860', Winnie Y.L. Chan examined the construction of Cantonese garden culture as a product of foreign trade and influenced by 'evidential research' (kaozheng 考證) related to local landscape history. The final paper 'Disorganized Imagination: Elements of the Garden in Early Modern Chinese Architecture' by Duan Jianqiang (Henan University of Technology) sought to redefine traditional garden practices from various contemporary architectural perspectives. The session successfully addressed different aspects of garden research ranging over methodology, the use of textual and visual sources, as well as questions related to the role gardens played in Chinese society. Discussions involved the Ming art historian Craig Clunas, Susan Wilson (University of Bristol) who is doing work on the transnational transfer of the Swiss chalet in English gardens, and Bogdan Stamoran (Leiden University), among others. Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes:[1] The 37th Association of Art Historians Annual Conference http://www.aah.org.uk/page/3234 (last accessed on 3 May 2011). [2] See Andong Lu, 'Deciphering the reclusive landscape: a study of Wen Zheng-Ming's 1533 album of the Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician', Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes, vol.31, issue 1 (2011):40-59. [3] Craig Clunas, Fruitful Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China, London: Reaktion Books, 1996. |