NEW SCHOLARSHIP

Felice Beato—A Photographer on the Eastern Road | China Heritage Quarterly

Felice Beato—A Photographer on the Eastern Road

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

7 December 2010–4 April 2011

A review by Lois Conner

Over the years the work of the New York-based photographer Lois Conner has often appeared in the pages of this journal. In April 2011, I was able to join Lois in Los Angeles where we visited a major exhibition of the work of the Italian-British photographer, Felice Beato (1832-1909) at The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Fig.1

Prince Kung, negative 2 November 1860, print 1861. Lithograph from a photograph. From Anne Lacoste,

Felice Beato--A Photographer on the Eastern Road, p.10

Beato was the first photojournalist to follow war closely, and he made unique photographic records of devastation wrought in the wake of the British empire's mercantile and military expansion. Those familiar with the infamous foreign incursion that struck at Beijing, the imperial capital of Qing dynasty, and that led to the devastation of the Garden of Perfect Brightness to the city's northwest in the autumn of 1860, will certainly know Beato's work.

A precious few images record scenes of the magnificent gardens destroyed that year, and his portrait of Prince Kung (恭親王, Yixin 奕忻), the man on whose shoulders the responsibility fell to finalise a settlement with the invading Anglo-French expeditionary force and its plenipotentiary Lord Elgin in wake of the devastation, is a study of exhausted grandeur and benighted dignity. Even some of the famous drawn and painted images of the expedition produced at the time by such illustrators as Charles Wirgman for the Illustrated London News were based on Beato photographs.

Of course, Beato's work was hardly limited to the aftermath of imperial war; he also created a body of luminescent art that reflects the culture and majesty of the countries in which he travelled and worked.

I have invited Lois to comment on three works from the Beato show at the Getty, allowing her eye to guide ours as we reconsider this extraordinary artist.—The Editor

The three photographs reproduced below were made by Felice Beato. Each of these are direct contact albumen silver prints made from wet collodion glass-plate negatives, printed by Beato himself (© The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Partial gift from the Wilson Centre for Photography). The sizes of the prints are: 24.2 x 30.1 cm, 22.3 x 30 cm, 26.2 x 29.9 cm, respectively.

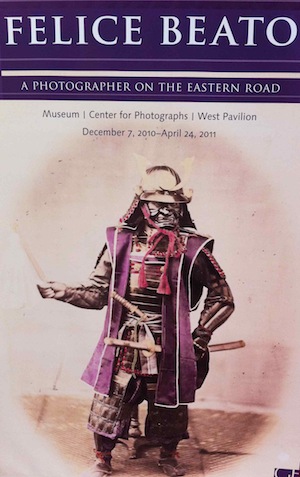

Poster for the exhibition.

'Felice Beato—A Photographer on the Eastern Road' is a stunning, and long overdue retrospective exhibition of this great nineteenth-century photographer. It focuses on his work from the Near and Far East, where he photographed extensively for over fifty years. It was marred only by the visual oddness of the 'reproductions' of most of the China images. Upon returning to Britain in 1861, Beato sold a group of photographs to another photographer, Henry Hering, who subsequently re-photographed the set and made his own glass plates for reproduction, although he did retain Beato's credit as the photographer of the originals. The subsequent mass reproduced prints—sold widely in England and elsewhere—suffer from a considerable loss of detail in the highlights, and are much flatter in tone (they lack the typical deep inky purple shadows of the originals). Beato was a superb technician, a consummate artist, going to extremes, and inventing his own path along the way. Some of the reproductions then do not reflect well on this, for the time, rare talent.

The work of Felice Beato and the range of imagery in the exhibition is unprecedented. For the first time, a large group of the panoramas are presented, some nearly eight-feet long. The panoramas allow us to see another kind of landscape, one which takes in the physicality of the sweep of the land, beyond our peripheral vision. Perhaps inspired by the paintings of the time, which were an attempt to make things more real, such as Louis Daguerre's theatrical dioramas accompanied by sound, wind and a shaking of the canvas. Taking in the breadth of the landscape, Beato's works are usually delineated by walls, roads or tracts of water. As they move us through the landscape, whether it is the gate of a city, as 'Panorama of Pekin, Taken from the South Gate, Leading into the Chinese City', or the fleet of war— Panorama of Hong Kong, Showing the Fleet for North China Expedition, we can see or 'read' the pictures as a narrative.

The result is a stunning and memorable exhibition that has a valuable body of reproductions in the accompanying book (Anne Lacoste, ed., Felice Beato—A Photographer on the Eastern Road, with an Essay by Fred Ritchin, LA: Getty Publications, 2010, 202pp), which, along with the diverse selection of panoramas, includes images of war, and landscapes from throughout Southeast Asia, and portraits from the studio as well as in the street.

Image One: Chutter Manzil Palace, With the King's Boat in the Shape of a Fish. First attack of Sir Colin Campbell in November, 1857, Lucknow, 1858

This is one of my favorite photographs from the show (and the first plate in the book). First of all, it's a great boat (with rattan scales no less), one seemingly half-imagined and fictional, as many of the truly magnificent things in India often are. The photograph lives up to this expectation. The way the boat fits into the space delineated by the water, while barely being submerged, is magical. The lyric arc of the back fin (and that little bit of light around it) pushes the boat and our eyes forward towards the Palace, while our eyes meander past the tilting two-masted schooner. The inclusion of the beautiful triad of figures echoes the suite of the three buildings flanking the Palace, thus furthering the surreal quality of the image.

Image Two: Angle of North Taku Fort at which the French entered, 21-22 August 1860

Made just before the Civil War in America, during which time Timothy O'Sullivan would also grapple with how to depict the horrors of war while using a cumbersome camera on a tripod, wet plate glass negatives that required precision and at least thirty minutes to process. Travelling with the British troops, Beato photographed this battle from several points of view. From the exterior you see broken fences, crumbling walls and the ladders used to hasten defeat. Mesmerized by the slain enemy inside the fortress, he rearranged their bodies (you can see the drag marks on the ground) to exaggerate and intensify what he saw, horrifying even the Captain in charge.

But what Beato created is something that words can't adequately describe. The image is both macabre and beautiful. The men are laid to rest, bodies aslumber, cannon balls piled up like severed heads. The triangle made by the nearest brace an exclamation point, an altar. Ladders, powerful symbols of this defeat, reach into a blank sky. The result is a powerful meditation that rivals Picasso's 'Guernica' which was, incidentally, inspired by a photograph.

Image Three: Interior of the Secundra Bagh After the Slaughter of 2,000 Rebels, Lucknow, 1858

These rebel bodies were gathered from a healed battlefield, and placed, along with the figures by Beato to form a narrative. This brutal battle had occurred six months before. With the dry dusty earth his palette, Beato disinterred and gathered clothes, heads, bone shards, ribs, and so on. Shattered doors from the Bagh probably served as stretchers for the detris. It was a battle fought, but nearly forgotten, were it not for his recreation—a photographic memento mori. Beato was not the first war photographer, but he was the first to cover several wars, create connected visual narratives and the first to photograph the bodies (of the defeated enemy only).

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly: