|

|||||||||

|

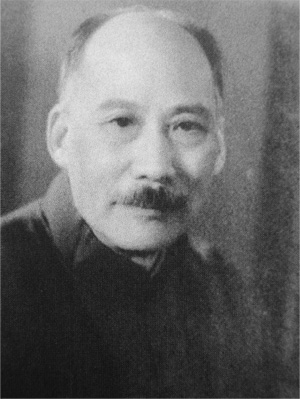

NEW SCHOLARSHIPQuestions of authenticity: Huang Binhong and the Palace MuseumClaire Roberts Fig.1 Portrait of Huang Binhong taken by Lang Jingshan in Shanghai in 1931 (Collection of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou). It can be difficult to determine the authenticity of a Chinese painting, particularly given the long tradition of artists copying and imitating works of art in order to master an earlier style. Copying was also a means of reproducing an artwork and transmitting its style. Many attributions of works from dynastic times are therefore contested.[1] In the past, when there were no public museums, photographs, print materials, catalogues raisonné, or the Internet, access to artworks was extremely limited. Connoisseurship was based on what a person had read and seen first hand—their familiarity with art history and documented texts, knowledge of the artist's work and life, use of brush, ink and compositional principles, and the scrutiny of inscriptions and colophons, seals and the age of the silk or paper. Connoisseurship trained the eye and and was part of the traditional education of a scholar-painter. It was not a professional art or science. Huang Binhong (1865-1955) was an artist and a connoisseur of the old school who drew on the sum of his accumulated knowledge and experience in both his creative work, and in his endeavours as a connoisseur. Later artist-collector-connoisseurs, such as Wu Hufan (1894-1968), C.C. Wang (1907-2003), and art historians who followed them, introduced new approaches to connoisseurship including the use of photography, and the systematic analysis of style, materials and techniques. In recent times, museums have employed scientific analysis and laboratory research in their quest for answers about the age and authorship of art works.[2] Despite these developments, connoisseurship remains a difficult and recondite art, based on training and experience, for which there is no rule book.[3] It is precisely because sometimes there is no way to determine that a painting is by a particular artist, or painted at a particular time, that attributions continue to be debated. In recent times, there has been some comment and misinformation about judgments made by Huang Binhong regarding the authenticity of artworks in the collection of the Palace Museum that was part of the long-running court case against the director of the Palace Museum Yi Peiji that lasted from 1935 to 1937.[4] For example, Jeannette Shambaugh Elliot and David Shambaugh remark in the recently published book The Odyssey of China's Imperial Art Treasures:

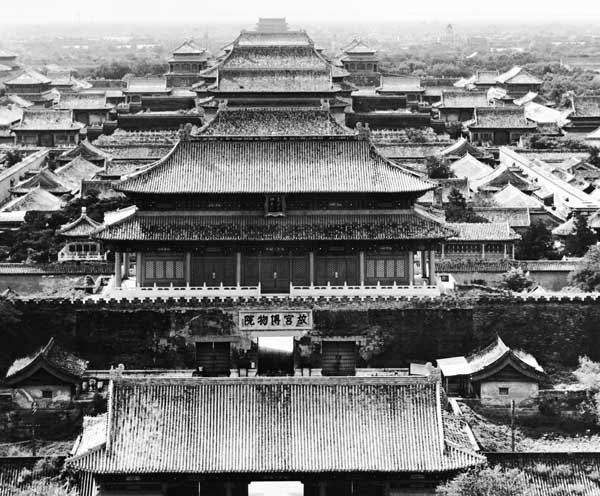

In late 1935, Huang Binhong was one of a number of experts engaged by the Capital District Court in Nanjing, to scrutinise the authenticity of artworks in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beiping.[6] Huang was contracted to appraise calligraphy and paintings, and not bronze or Buddhist objects. His contract related to a legal case that had been brought against the museum director, Yi Peiji (1880-1937) and others, who were alleged to have misappropriated artworks and replaced them with fakes.[7] The information provided by the appointed experts would be used in the prosecution of the case against Yi Peiji and two other staff of the Palace Museum.  Fig.2 Photograph of Huang Binhong taken in Beiping (Collection of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou). Rather than viewing the appriasals made by Huang Binhong and others as 'new mistakes', it is worth considering them as part of the continuing assessment of artworks that is the stuff of connoisseurship and the attempts by connoisseurs and art historians over time to place artworks within an historical continuum. While Huang Binhong's expertise in authentication and assessments of his judgments by later scholars await detailed examination, archival research can shed some light on Huang Binhong's involvement in the 1930s' appraisal of the artworks in the collection of the Palace Museum.[8] Huang Binhong's prominence as an art historian and connoisseur, through his involvement with publications such as A Collectanea of the Arts (Meishu congshu) and The Glories of Cathay (Shenzhou guoguang ji) as well as his connection to Ye Gongzhuo (1881-1968) and Yu Youren (1879-1964), who occupied positions of power and influence within the Nationalist government, were instrumental in his being appointed to this position.[9] The fact that much of the collection had been transported to Shanghai, where Huang was resident, and that he was not from Beiping, were also likely to have been factors that influence the decision to engage him in this task. The job provided a good salary of 500 yuan per month and Huang would have appreciated the opportunity to view works of art in the former imperial collection. The Palace Museum had been established ten years earlier in the grounds of the Forbidden City, its creation a direct consequence of the fall of the Qing dynasty. After the 'last emperor', Aisin Gioro Puyi (1906-1967) was forced to leave his quarters in the inner court on 5 November 1924, the government moved quickly to transform the privileged domain of the imperial family, and its repository of treasures amassed by successive emperors, into a public institution. On 10 October 1925, the Palace Museum was opened to the public for the first time. For the new regime, it was symbolic of a new order.  Fig.3 Photograph of the Palace Museum, Beiping, taken by Hedda Morrison, resident in Beiping 1933-46 (Collection of the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney). Yi Peiji was appointed Director of the Palace Museum by the Nationalist government in February 1929, although he had been instructed to take responsibility of the museum the preceding year. Yi had had a close involvement with the museum since 1924 when he officiated at meetings of the Committee for the Disposition of the Qing Imperial Household (Qingshi shanhou weiyuanhui) as Wang Jingwei's representative. Yi was from Hunan and had worked as a teacher, principal and senior government official in his home province. In 1922, he was appointed as an advisor to Sun Yat-sen, Grand Marshall of the People's Republic of China government in Guangdong (Zhonghua guomin zhengfu) and President of the Nationalist Party. In the 1920s he occupied various high-level positions including that of Sun Yat-sen's representative in Beiping, President of the National Labour University in Shanghai, and Minister of Agriculture and Mining.[10] In 1933, however, following a protracted dispute within the Palace Museum, Yi Peiji was accused of misappropriating antiquities and precious gems from the Palace Museum and arrested. The following year, the court began to investigate the case and Yi Peiji resigned as museum director.[11] The court-led inspection of the Palace Museum collection began in Shanghai, much of the collection of calligraphy and painting having been transported there during 1933 as a precaution against possible war with Japan.[12] Shanghai had plentiful storage space and the objects would stay there until a new branch museum and purpose-built storage facility was constructed in Nanjing, the new capital.[13] The inspections began in February 1934 with the jewelry collection. The review of calligraphy, painting and bronzes commenced in late December 1935.[14] In a letter to Xu Chengyao, an old friend from his ancestral home of Shexian, Huang Binhong talked about working in the vault of the Central Bank in Shanghai during the investigations and the pressure he was under to authenticate a large number of paintings within a six-month period:

Huang Binhong's notes on the works he viewed are concise and to the point.[16] The determination of authenticity is, in most cases, summarised by a single word or phrase, for example authentic (zhen 真), forgery (wei 偽), old forgery (jiu wei 舊偽), appears to be a forgery (si wei 似偽), traced copy (moben 摹本), recent copy (jin linben 近臨本) or a comment such as 'not a Song dynasty painting, rather the work of an artist of the Ming period'. In the case of questionable works, the assessment was briefly explained, for example:

In the foreword to his personal report on the assessment of paintings and calligraphy, Huang expressed confidence in his ability to judge fakes or weipin , based on an awareness of the historical periods and styles, familiarity with art theory and practice and an examination of the materials, inscriptions and seals. He defined and distinguished two types of copies, a freehand copy or linben, and a traced copy which was known as moben:

Historically, paintings were copied as part of a course of study in order to absorb the spirit of ancient masters and transmit their styles. As Huang suggests in the quotation above, artists made different types of copies, but for very different reasons. Copies were not necessarily made to deceive the viewer. The existence of copies in the imperial collection, or works of uncertain authorship, date or provenance, was therefore inevitable. In letters to friends Huang conveys his excitement at viewing the imperial collection—the ultimate art collection for a Chinese connoisseur—and a desire to record information that would further art historical research and stimulate his own artistic practice. The time he had to view each artwork was very limited, but he did all he could to remember the treasures that he saw. In letters to Xu Chengyao, Huang expressed delight in works that were produced in the county of Shexian where:

Looking back on the experience, he observed:

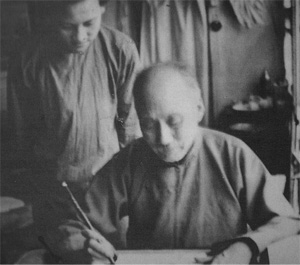

In Shanghai, from December 1935 to April 1936, Huang Binhong documented and appraised over 2,000 works of art, an average of more than twenty works per day. From June to July 1936, he inspected calligraphy and paintings at the Palace Museum in Beiping and in August he was asked to examine a collection of seals and curios. In September 1936, Huang was engaged for another three months to examine more works stored in Shanghai. On this occasion there were two groups of people undertaking the inspections, referred to in the final report as Group A and Group B. Huang was Group A, but it is unclear who represented group B. From early January 1937, Huang appraised a final group of works stored in Nanjing over a three-month period. By the end of the fourth and final period of inspection, Huang Binhong had sighted and written appraisals for close to 5,000 calligraphic works and paintings from the collection, many of them with multiple parts—for example, one item was a crate containing 294 painted fans.[21] The job had taken the seventy-year old artist and connoisseur twelve months, spread over one and a half years, which was double the time initially suggested.  Fig.4 Photograph of Huang Binhong painting at home in Beiping, with his son looking on (Collection of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou). Huang Binhong had been under considerable pressure to examine thousands of artworks and make individual assessments in a short period of time. An official version of his records and those of the other appointed experts was prepared by the court and published in late 1937. While he was contracted to appraise the entire collection of calligraphy and paintings, it is clear from his recollection above that this was not possible. Judging from Huang's hand written reports, he took the job seriously, but for the court it appears to have been a somewhat perfunctory exercise. A question that remains to be answered, of the court and bureaucrats who framed the legal case, is how could an assessment of the authenticity of artworks in the collection of the Palace Museum, a collection that inevitably contains various kinds of copies and works of uncertain provenance, be used as hard evidence to prove the culpability, or clear the name, of the Director? While discepancies exist between the old object records and the new assessments, the circumstances under which both sets of records were made were far from ideal. In deciding to accept the job, Huang Binhong agreed to receive a salary and access to the imperial collection, both significant incentives for an artist and connoisseur. In return, he would provide the court with an expert opinion on individual works of art. It was a transaction, but one that occurred in an institutional context that was highly politicized and factionalised. The ramifications of the court-led inspections were significant and wide reaching. Yi Peiji died in 1937, a sick and broken man, the case unresolved and his reputation tarnished. It was not until 1948, after the death of Zhang Ji who brought the charges against Yi Peiji, that the case was finally dropped. It is now widely acknowledged that the case was trumped up and manipulated by Yi Peiji's adversaries.[22] But, according to the Huang Binhong scholar Wang Zhongxiu, this was not the situation at the time the charges were made.[23] It would appear that the case was also intended as a warning to those who had for years exploited and plundered the Palace Museum collection for personal gain. After the conclusion of the court-led inspections, artworks that were determined by the court to be useful as evidence in the ongoing legal case were sealed in crates and held in storage. During the Sino-Japanese War (1937-45) the core of the Palace Museum collection—although not including the crates sealed by the court—was transported inland for protection in one of the most remarkable and complex movements of a museum collection. In 1948, when it became clear that the Communist Party would win the civil war, the Nationalist government hurriedly shipped many of the most important objects in the imperial collection to Taiwan. After 1949, the crates that had been sealed by the court in the 1930s, and which remained on the mainland were finally opened. As a result of later judgments by Palace Museum staff, a number of the paintings that Huang Binhong questioned are now believed to be genuine. Notable among these are Song Huizong's Ting qin tu and Ma Lin's Ceng die bing xiao tu. As might be expected, a number of scholars outside the Palace Museum continue to debate the authorship and date of these and other works.[24] It is ironic that, because of Huang Binhong's 'new mistakes', the above-mentioned paintings remained on the mainland and are today regarded as national treasures in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. The court-led inspections thus came to play an unexpected role in the division of the imperial collection between the Palace Museum, Beijing and the National Palace Museum, on Taiwan. Owing to the politicization of the Yi Peiji court case, Huang Binhong's appraisal of paintings and calligraphy has not been accorded legitimacy by the Palace Museum.[25] After all, Huang Binhong was appointed by the court, not the museum. Prior to and following Huang's appointment, groups of experts have worked to document and authenticate works in the collection of the museum. It is these appraisals by museum-designated experts that have primarily determined the attribution of works of art in the collection of the Palace Museum. The judgements of later scholars have invariably benefitted from developments in connoisseurship over the last seventy years and access to visual and textual information that was not previously available. Huang Binhong's assessments are part of the history of connoisseurship of objects in the imperial collection and should be acknowledged as such. What is needed is a detailed study of Huang Binhong's appraisals of works of art that are now housed in the National Palace Museum, Taiwan and the Palace Museum, Beijing. Attributions will continue to be contested and the debate will continue. That is the stuff of connoisseurship and art history. [© Claire Roberts] Notes:[1] See Judith G. Smith, ed., Issues of Authenticity in Chinese Art: Papers prepared for an international symposium organised by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in conjunction with the exhibition 'The Artist as Collector: Masterpieces of Chinese Painting from the C.C. Wang Family Collection' (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999). [2] See Xue Yongnian, 'Shuhua jianding yu mingjia yaolun', Gugong bowuyuan yuankan, vol.2, 2002, pp.77-84; Clarissa von Spee, 'A Modern 'Traditional' Connoisseur: Wu Hufan's (1894-1968) use of photographic reproductions in his inscriptions on calligraphy and paintings', a paper presented at the Shanghai School of Painting Symposium, Shanghai, 16-19 December 2001; and, Maxwell K. Hearn, 'A Comparative Physical Analysis of Riverbank and Two Zhang Daqian Forgeries, in Judith G. Smith, ed., Issues of Authenticity in Chinese Art, pp.95-113. [3] Jerome Silbergeld, 'The Referee Must Have a Rule Book: modern rules for ancient art', in Judith G. Smith, ed., Issues of Authenticity in Chinese Art, pp.149-152. [4] See Na Zhiliang, Dianshou gugong guobao qishinian (Beijing: Zijincheng chubanshe, 2004), p.33; Na Zhiliang, Gugong sishinian (Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan, 1976), pp.64-66; Yang Renkai, Guo bao chen fu lu: Gugong sanshi shuhua jianwen kaolüe (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin meishu chubanshe, 1991), p.59; and, Jeanette Shambaugh Elliott with David Shambaugh, The Odyssey of China's Imperial Treasures (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2005), p.77. See also China Heritage Quarterly, No. 4 (December 2005), which took as its focus the eightieth anniversary of the Palace Museum. http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/ [5] Jeanette Shambaugh Elliott with David Shambaugh, The Odyssey of China's Imperial Treasures, p.77. The orginal source for these figures is Nanjing shoudu difang jianchayuan ed. Yi Peiji deng qinzhan Gugong guwu an jianding shu, volume 1, 1937, but there is no reference anywhere in this document to Huang Binhong or any of the other experts contracted by the court. The figures are also quoted by Na Zhiliang, Gugong sishinian, p. 66. Na refers to the total number of objects sealed in crates by the court, as part of the court-lead inspection process. He does not refer, here, to Huang Binhong or link his name with the judgments on all of those objects. Earlier, Na refers to Huang's appraisals of calligraphy and paintings (pp.64-65). [6] Huang Binhong's contract document is dated 1935 and is to be found in the collection of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou (03993). The conditions are specified on the reverse: '1. To authenticate the entire group of calligraphy and paintings; 2. The duration is tentatively set at six months. Depending on the amount of work required, this period can be extended or shortened; 3. The fee for authentication is fixed at no more than five hundred yuan per month per person; 4. Authentication must be carried out in accordance with legal procedures involved in a lawsuit as stated in article 189 [of the civil code of the Republic of China]; 5. Produce a written report; 6. The hours for authentication each day will be governed by the opening hours of the Central Bank; 7. At the completion of the period of authentication a report must be submitted. If the report has not been completed and more work is required, there will be no further payment'. [7] See Wu Jingzhou, Gugong daobao an zhenxiang (Beijing: Wenshi ziliao chubanshe, 1983); and, Jeanette Shambaugh Elliott with David Shambaugh, The Odyssey of China's Imperial Treasures, pp.75-78. [8] Some of the material in this essay is taken from my, The Dark Side of the Mountain: Huang Binhong (1865-1955) and artistic continuity in twentieth century China, a work currently being prepared for publication. [9] See Wang Zhongxi ed., Huang Binhong nianpu (Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 2005), p.369. [10] See Na Zhiliang, Gugong bowuyuan sanshi nian zhi jingguo (Taipei: Zhonghua congshu weiyuanhui, 1957), pp.11, 298-300; and, Jiang Shunyuan, 'Jinian Yi Peiji xiansheng', Gugong bowuyuan yuankan, vol.4, 1987, pp.40-44. [11] Na Zhiliang, Gugong bowuyuan sanshi nian zhi jingguo, p.300. [12] 128 crates containing some 9,000 works of calligraphy and painting, the core of the Palace Museum collection, were transported to Shanghai. See Na Zhiliang, Gugong bowuyuan sanshi nian zhi jingguo, pp.101, 108-109. [13] The idea to build a branch museum and storage facility in Nanjing was raised in July 1933, decided upon in April 1934 and, in April 1935, the site of Chaotian gong was chosen. See Na Zhiliang, Gugong bowuyuan shanshi nian zhi jingguo, pp.151-154, 300. [14] Huang began the inspections on 20 December 1935 and finished on 28 April 1936. Wang Zhongxiu, ed., Huang Binhong nianpu, p.371. [15] Huang Binhong, letter to Xu Chengyao, dated 13 January 1936, Huang Binhong wenji, shuxin bian (Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 1999), p.146. [16] The majority of the records relating to Huang's inspection of paintings and calligraphy are included in Huang Binhong wenji, jiancang bian, pp.27-577. The two numbers given to each item record the order in which Huang Binhong viewed the works and the original inventory number assigned to the object by the Palace Museum. In creating the record published in Huang Binhong wenji<, the editor Wang Zongxiu has drawn on both Huang's handwritten notes, which are in the collection of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, and the entries in the final report published in 1937 as Nanjing shoudu difang jianchayuan ed.Yi Peiji Deng Qinzhan Gugong guwu an jianding shu. See Wang Zhongxiu, ed., Huang Binhong wenji, jiancang bian, p.27. See also R.H. van Gulik, Chinese Pictorial Art as Viewed by the Connoisseur, p.396. [17] Wang Zhongxiu, ed., Huang Binhong wenji, jiancang bian, pp.35-36. [18] Ibid., p.27. [19] Huang Binhong, letter to Xu Chengyao, dated 13 January [1936], Huang Binhong wenji, shuxin bian, p.146. [20] Huang Binhong, letter to Fu Lei, dated 14 December [1943], in Wang Zhongxiu, ed., Huang Binhong wenji, shuxin bian, pp.210-211. [21] Huang Binhong's four periods of inspection were as follows. First period: 20 December 1935 to 28 April 1936, Shanghai (calligraphy and paintings, 2145 works); Second period: 1 June to 22 July 1936, Beiping (remaining calligraphy and paintings, 478 works) and from 30 July to 6 August (seals and curios); Third period: 4 September to 2 December, Shanghai (calligraphy and painting, 945 works); Fourth period: 1 January to 15 March 1937, Nanjing (calligraphy and painting, 1029 works) and 26 March to 1 April 1937, Nanjing (calligraphy and paintings, 39 works). See Wang Zhongxiu, ed., Huang Binhong nianpu, p.371; and, Wang Zhongxiu, ed., Huang Binhong wenji, jiancang bian, p. 577. Na Zhiliang refers to eleven crates of artworks sealed by the court that had been transported to Nanjing. See Na Zhiliang, Gugong bowuyuan sanshinian zhi jingguo, p.155. [22] Wu Jingzhou, Gugong daobao an zhenxiang; Jiang Shunyuan, 'Jinian Yi Peiji xiansheng', p. 48; Na Zhiliang, Gugong sishinian, pp.64-65; and, Jeanette Shambaugh Elliott with David Shambaugh, The Odyssey of China's Imperial Treasures, pp.75-78. [23] Wang Zhongxiu, 'Huang Binhong shishikao zhi shi (shang), Rongbaozhai gujin yishu bolan, 11 (2002), p.240. [24] Ibid, pp.235-238. [25] Interview with Zhu Jiajin, Palace Museum, 9 November 2001. |