|

|||||||||

|

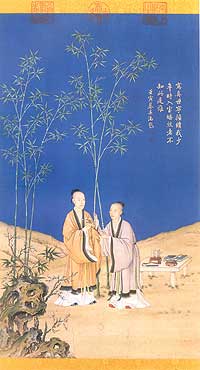

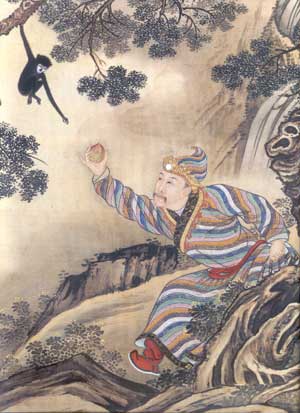

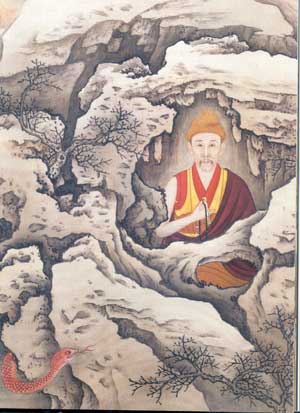

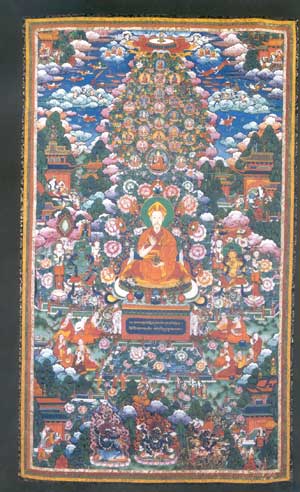

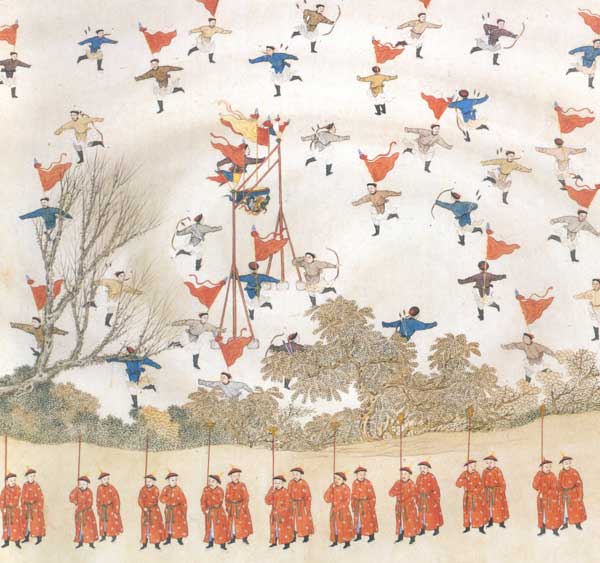

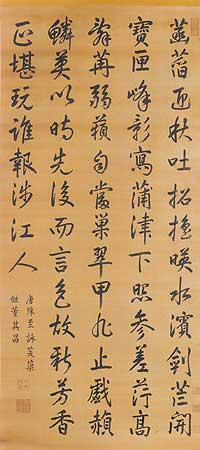

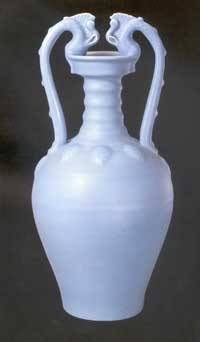

NEW SCHOLARSHIPBOOK REVIEWEvelyn Rawski and Jessica Rawson, eds., China: The Three Emperors, 1662-1795, London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2005, 494 pp., more than 500 coloured illustrations, 2 maps, 2 plans Fig.1 Despite its understated title, this impressive volume is a lavishly illustrated companion to China's final era of imperial grandeur – the heyday of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) under the rule of the Kangxi (r. 1662-1722), Yongzheng (r. 1722-1735) and Qianlong (r. 1736-1795) emperors. The editors adroitly marshalled the talents of more than two dozen scholars whose expertise sheds light on the history, personalities and, above all, the art of an age in which the Chinese empire was the equal of any contemporary royal court and its dominions. Co-edited by Evelyn Rawski, one of the leading Qing historians in the United States, and Jessica Rawson of Merton College, Oxford, who has curated several major exhibitions of ancient Chinese art and archaeology, the volume demonstrates the strength of drawing on nearly thirty scholars to clarify the significance of the material presented in its pages. Succinct articles are complemented by the essay-like captions covering such diverse areas as painting, porcelain, calligraphy, metalwork, jade carving, costume and the array of handicrafts perfected in the imperial workshops of the Qing palaces. The volume takes its place beside fine catalogues produced in recent years, such as Turks: A Journey of a Thousand Years, 600-1600 edited by David J. Roxburgh et al (also published by Royal Academy Publications), and Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261-1557) edited by Helen C. Evans and published by the Metropolitan Museum. These three catalogues form a benchmark in such productions as they transcend the exhibitions they document to become major historical studies that bring to life the material and periods they chronicle. Although this review is concerned only with the catalogue, some background information about the exhibition sheds light on its genesis. The exhibition China: The Three Emperors, 1662-1795, mounted at the Royal Academy of Arts from November 2005 to April 2006, was three years in the making. It was curated by Jessica Rawson, together with Alfreda Murck and Regina Krahl. If there was a model for the exhibition, it was Splendors of China's Forbidden City: The Glorious Reign of Emperor Qianlong, curated by Bennet Bronson and Chunmei Ho for the Field Museum of Chicago in 2004. Even though the show at the Royal Academy of Arts was prepared in a rush, as the opening was moved forward by two months to coincide with Hu Jintao's visit to London, the exhibition volume bears no traces of this.  Fig. 2 Ancestral portrait of the Kangxi Emperor in court dress, hanging scroll, colour on silk, Palace Museum, 278.5 x 143 cm, cat. no. 1, p.69 China: The Three Emperors, 1662-1795 presents us with alternating images of the three emperors. By turns we see them engaged, or even submerged, within the spectacle and pomp of the massive empire that they ruled; as private individuals either at leisure, in pursuit of the spiritual or as scholars in the surrounds of their studies; and in the conventional, impersonal and impervious guises that they chose for posterity. In explaining the ritual function that imperial portraiture fulfilled in ancient China, Jan Stuart ('Images of imperial grandeur', pp.64-75) clarifies the conventions that placed restraints on the images we have received of enthroned emperors. These austere portraits (Fig.2) were prepared for posterity and intended to transcend all notion of temporality (even the season and time of day) and also to only reveal the transcendent personality. Thus full realism was eschewed. She describes the context in which these imperial portraits or 'sacred likenesses' (shengrong, yurong and shenyu) were viewed, away from the modern museum: 'Only when they are imagined as the centre of a multi-sensory spectacle, with heady, perfumed incense smoke veiling the sitters' visages, with the sounds of rustling silk garments and tinkling jade girdle ornaments overheard as viewers kowtow and prostrate themselves before the paintings, and with their jewelled colours and accents of gold dancing in flickering candlelight do the portraits assume their intended magnificence' (p.67).  Fig. 3 Photograph from the 1930s showing the altars and ancestral portraits in Shouhuang Dian. Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing Such portraits were housed in the ancestral hall of the imperial clan. This hieratic portrait of the Kangxi Emperor was hung, eight months after his death, in the Hall of Sovereign Longevity (Shouhuang Dian), a major hall erected by the Yongzheng Emperor for his father and later renovated by the Qianlong Emperor. This ancestral hall for the Qing emperors and the Qianlong Emperor in particular once stood in Jingshan, the imperial park opposite the north gate of the Forbidden City. Jan Stuart's article includes a photograph from the 1930s (Fig.3), and now in the collection of the Palace Museum, showing a wall of imperial portraits behind the silk draped altars covered with ritual vessels in Shouhuang Dian.  Fig.4 Giuseppe Castiglione, Spring's peaceful message, hanging scroll (originally attached to wall panel), ink and colour on silk, Palace Museum, 68.8 x 40.6 cm, cat. no. 186, p.276 Far more intimate portraits of these three emperors provide us with insights into their personalities that are impossible to obtain for rulers of earlier times. The cover of the work is graced by a full-length portrait of the young Qianlong with his father, Yongzheng, and this was one of the major works in the exhibition (Fig.4). The inscription records Qianlong's comment on the work by Giuseppe Castiglione (Chinese name: Lang Shining; 1688-1766): 'In portraiture Shining is masterful, he painted me during my younger days; the white-headed one who enters the room today, does not recognise who this is. Inscribed by the Emperor towards the end of spring in the year 1782'. Although Wu Hung has noted elsewhere that this painting is less a portrait than a portrayal of the succession – symbolised by the flowering sprig, Michèle Pirazzoli-t'Serstevens in her description of the work in this volume highlights the background to this work and its artistic originality. The painting was originally affixed to a wall of a room adjoining the Qianlong Emperor's study in the Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin Dian) in the Forbidden City, where the emperor granted audiences, consulted members of the Cabinet and signed edicts. Only later was it removed and mounted on a scroll, to which the inscription was added in 1782. The inscription shows that, for the emperor, proof of his filial piety became less significant over time than the passage of time itself. The intense blue background was unprecedented in a Chinese painting, and the artist used this device typical of European illumination and miniature painting to highlight the sitters' faces and the bamboo.  Fig.5 Giuseppe Castiglione, The Qianlong Emperor in ceremonial armour on horseback, hanging scroll (originally attached to wall panel), ink and colour on silk, Palace Museum, 322.5 x 232 cm, cat. no. 65, p.166 Other portraits by anonymous court artists included in this volume depict the Kangxi Emperor reading, as well as seated in informal dress poised to write with a brush; Yongzheng reading; and Qianlong viewing scroll paintings in a garden and, as a young prince, seated in his study, practising calligraphy on a plantain leaf. Apart from these literati portraits, Kangxi is depicted in armour, while Qianlong is portrayed engaged in hunting as well as in ceremonial armour on horseback in a painting attributed to Giuseppe Castiglione (Fig.5). The presence of the latter painter in the atelier of the Qianlong Emperor is part of a wider phenomenon in which these three emperors were clearly not merely aware of European court practices but keen to adopt some aspects of foreign court life, such as the role played by the portrait painter in documenting palace life. Joanna Waley-Cohen explains the impact the Jesuits in particular had in providing the information and technology about the global environment the court was deemed to require in her essay 'Diplomats, Jesuits and Foreign Curiosities' (pp.178-207). Many of the objects included in the exhibition not only provide evidence of the Jesuit contribution to the court but also testify to the inspirational role China at this time played in the development of European Rococo art. The choice of Nie Chongzheng from the Palace Museum to write the essay on 'Qing Dynasty Court Painting' for the volume is judicious for he is fully cognisant that most innovative aspects of Qing court painting represented a fusion of Chinese and European painting techniques, rather than the simple imitation of the latter.  Fig.6 Yongzheng Emperor in Muslim costume by anonymous court artists, Album of the Yongzheng Emperor in costumes, one of fourteen album leaves, colour on silk, Palace Museum, 34.9 x 31 cm, cat. no. 167, p.250  Fig.7 Yongzheng Emperor as a meditating Tibetan monk by anonymous court artists, Album of the Yongzheng Emperor in costumes, one of fourteen album leaves, colour on silk, Palace Museum, 34.9 x 31 cm, cat. no. 167, p.251 The most idiosyncratic portraits of any of the three emperors in the volume, a set of 14 album leaves comprising 13 portraits of the Yongzheng Emperor in various ethnic costumes and roles, remain unmistakably Chinese, even when he is the only emperor depicted in an interpretation of European noble dress.(Figs.6&7) Jan Stuart in her full caption (pp.429-30) describing this album dissuades us from imagining that charades became a pastime at the Chinese court, possibly in emulation of traditions of masquerades that were a distinctive feature of European court life, as has been suggested by Wu Hung. She writes that it is generally agreed that the Yongzheng emperor never actually owned or wore the costumes depicted in the leaves: 'he never pierced his earlobes like a Mongol or wore a European wig. Confusion about Western dress corroborates the supposition that the painter did not see these exotic clothes first hand; for example, the European waistcoat and overcoat are not rendered faithfully and moreover are paired with a Chinese belt and shoes'. Stuart argues that these album leaves, rather than providing evidence of the introduction of charades to the Chinese court, may be part of a Chinese tradition documented in literary references from early as the Tang dynasty to the practice whereby emperors had their faces inserted into paintings of famous cultural heroes. For example, the Southern Song Emperor Lizong (r. 1225-64) commissioned a set of scrolls of Thirteen Sages and Rulers of the Orthodox Lineage depicting Taoist and Confucian sages with his own imperial countenance. She asks, 'Is the unusual number of thirteen leaves in this portrait album of the Yongzheng Emperor coincidental, or does it signal a conscious borrowing from this Song dynasty precedent?' (p. 429) Stuart notes that, in the album leaf in which he appears as a Gelugpa Tibetan lama in the hollow of a craggy mountain, 'he probably felt a level of personal identification.' Oblivious to a snake about to lunge towards him, the emperor-as-monk has attained a state through meditation that elevates him beyond the mundane. (Fig.7) Although the meaning and provenance of each leaf in this album remain impenetrable today, Stuart taps into the overarching significance of the work when she concludes: 'For the Yongzheng Emperor, the Ultimate Reality of his personal identity was multicultural and atemporal – an existence linked across geopolitical space to include Mongols, Zunghars, Tibetans, Chinese and Europeans and linked in time with past cultural heroes and sages'.  Fig.8 Anonymous, Qianlong Emperor in Buddha dress, from Puning Temple in Chengde (Jehol) and now in Palace Museum, c. 1758, thangka with inscription in Tibetan, colours on cloth, 108 x 63 cm, cat. no. 47, p.142 Europeans aside, the cement that bound these ethnic groups together was provided by the religious rituals of the ecumenical Manchu court. The sumptuous thangkas, silk embroidery, scriptures and votive objects demonstrated that no expense was spared in developing the court's links with shamanic and Buddhist theocratic institutions (Fig.8), as outlined by Patricia Berger in her essay 'Religion' (pp.128-153). The multicultural dimensions of the Manchus' frontier diplomacy, delineated by Evelyn Rawski's article on 'Territories of the Qing' (pp.154-177), cannot obscure the fact that the 'Qing dynasty was the most successful dynasty of conquest in Chinese history'. Rawski points out that the Manchus drew ultimately on the Mongol synthesis of the Tibetan notion of a reincarnate lineage of hierarchs and a Confucian Chinese notion of zhengtong which posited one legitimate line of rulers that transcended individual dynasties, while inheriting Chinese bureaucratic principles and personnel from the Ming dynasty and placing this under the overriding structure of the Manchu banner system. The distinctive ethnic makeup of the Qing imperium is well documented in the many scenes of martial pageantry executed by Qing court painters and included in this volume, its large-scale format ideal for presenting such monumental works depicting military victories and other ceremonies of state. Yao Wenhan's New Year's banquet at the Pavilion of Purple Brightness(Fig.9), for example, celebrates the victory of Qianlong over the Zunghars and Uighurs and his annexation of their territories around 1760. Gerald Holzwarth describes how the emperor had the old building in the park west of the palace restored and transformed into a military memorial hall and in 1760 added a second hall, the Hall of Military Success (Wucheng Dian). In the covered galleries connecting the two halls, stone slabs engraved with no less than 224 poems by the emperor praising the merits of his warriors were arranged. Inside the halls he displayed one hundred hanging scrolls with life-size portraits of Manchu, Chinese and Mongol officers and soldiers who had distinguished themselves in battle. The scrolls too were adorned with laudatory poems by the emperor. In addition, sixteen large paintings depicting famous battle scenes of the war were affixed to the walls. Weapons and banners captured in battle were also displayed. Holzwarth's notes on this work make it clear that the emperor and his army of painters were fully engaged in the execution of a prodigious output of which we only glimpse a fraction today. In the New Year of 1761, the victory was celebrated with a state banquet in front of the newly completed hall of fame, possibly the work depicted in this painting, and the painting includes the depiction of the ice games on the adjacent lake which were organised annually from 1745 onwards.  Fig.9 Yao Wenhan, New Year's banquet at the Pavilion of Pure Brightness, (detail showing winter games) handscroll, ink and colour on paper, Palace Museum, 45.8 x 486.5 cm, cat. no. 78, pp.174-77  Fig.10 Kangxi Emperor, Tang poem about the lotus in bloom written in the running script style of Dong Qichang, c. 1703, hanging scroll, ink on silk, Palace Museum, 186.7 x 85.3 cm, cat. no. 121, p.216 The fact that the three emperors celebrated in this volume also saw themselves as calligraphers, painters and poets whose works were core articles in so many celebratory and ritual events at court meant that they themselves played a central part in documenting their own substantial achievements. In this volume we can admire an example of the calligraphy of the Kangxi Emperor inspired by Dong Qichang, and described by Hua Ning and Shane McCausland as 'fresh, relaxed and elegant' in mood. (Fig.10) The latter scholars suggest that the emperor during his middle years made a close study of Dong's early calligraphy. Yet they note, in their description of another Tang poem in the hand of the emperor and executed in imitation of Mi Fu, that Kangxi did not limit himself to any particular school when he studied specimens of calligraphy, but 'applied himself equally to emulating masters from throughout the classical tradition', although it is recognised that he was particularly successful in imitating the style of Mi Fu. In calligraphy, Yongzheng was inspired by the early Yuan master Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), while Qianlong in turn was inspired by his grandfather, as well as Dong Qichang and Zhao Mengfu. The Yongzheng Emperor is described by Regina Krahl in her essay 'The Yongzheng Emperor: Art collector and patron' (pp.240-269) as 'the first true art-lover among the Manchu rulers. Unlike the more practically minded Kangxi Emperor, who believed himself duty-bound to look after items inherited from the past and to uphold standards of craftsmanship, the Yongzheng Emperor passionately cared for and lived with works of art' (p.244). Krahl describes how the Yongzheng Emperor brought pieces inherited from the Ming palace collections out of storage for display and inspection, and would commission paintings that faithfully reproduced the porcelain and other objects that he loved. The paintings of antiques that he commissioned reflected 'an art collector's approach rather than that of a guardian of historically significant relics'. From the beginning of his reign he had the artisans of the Palace Workshops craft pieces that exemplified his artistic taste, unlike his predecessor, Kangxi, who had been interested in the mastery of technical challenges. Yongzheng developed close working relationships with the artists and craftsmen from these palace studios; from his reign period we know the names of more than a hundred artisans who prior to then had been anonymous.  Fig.11 Tang dynasty style amphora with 'clair-de-lune' (tianlan) glaze produced at Jingdezhen during the Yongzheng reign, Palace Museum, height: 51.8 cm, cat. no. 177, p. 264  Fig.12 Decorative vessel made for the Qianlong Emperor in the shape of an ancient bronze wine vessel (you), carved bamboo root, Palace Museum, 17 cm, cat. no. 206, p.289 Yongzheng sought to revitalize the declining art of porcelain and was instrumental in appointing the artist Tang Ying (1682-1756) to direct the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen. Shapes of the Tang, glazes of the Song and patterns of the Ming were rediscovered by the potters working under Tang Ying's magisterial direction for the emperor. (Fig.11) Krahl makes the point that Yongzheng's fascination with antiquity, his collecting of antiques and his resulting passion for archaism, combined with his personal taste, demand for quality and engagement of contemporary craftsmen, gave Qing art its identity and shaped our idea of Chinese art in general. She writes that his legacy left little for his successors to develop, and the Qianlong Emperor concentrated on increasing the scale and ostentation of works, and connecting himself to his patrimony by marking, stamping and inscribing the works of art he inherited, as well as having them reproduced in other materials. (Fig.12) Jessica Rawson in 'The Qianlong Emperor: Virtue and the possession of antiquity' (pp.270-305) is less damning in her appraisal of what she characterises as Qianlong's enthusiasm for antiquities. Rawson notes that Qianlong's seals, inscriptions and other 'conspicuous visual interventions' that for some compromise the integrity of objects also allow us to detect how he saw himself in a long lineage of China's rulers. She draws attention to his passion for ancient bronzes and how he revived the practice of cataloguing collections of antiquities that had flourished in the Song dynasty but languished under the subsequent Yuan and Ming dynasties. The most enduring of his ventures to preserve and present the past was his enterprise to collect all the great texts of his empire in Siku quanshu (Collection of the Four Treasuries). He thus encouraged scholarship and publication, thereby playing a major role in the revival of classical studies that would continue on into the 19th century. This was, however, possibly ancillary to his own ambitions; 'the immense textual compilations were effective instruments to ensure that his contemporaries and future generations recognised the Qianlong Emperor as taking the pre-eminent role in preserving and transmitting the glories of China's classic heritage'. (p.275) Masterpieces of painting by scholar artists are also housed in the palace collections, and these are discussed by Alfreda Murck in 'Silent satisfactions: Painting and calligraphy of the Chinese educated elite' (pp.306-355). The works to which Murck introduces us, both in her essay and captions (pp.450-465), are the dissonant and alternate voices of artists of the period who were often characterised as individualists or even eccentrics. However, most of these paintings entered the collection of the Palace Museum in the 20th century and do not reflect the taste of the three emperors. Murck's section of the book is valuable not simply for the aesthetic treat these masterpieces constitute, but also for the contrast that the wider view of painting beyond the court provides. It is fascinating, for example, to compare the works of Wang Hui (1632-1717) in his capacity as director of the palace atelier, with his work for a private client. He was responsible for the planning and supervision of the massive handscroll originally in twelve sections The Kangxi Emperor's southern inspection tour (cat. item 13), which depicts the journey of the Emperor and his entourage undertaken in 1689. Wang Hui was responsible for the conceptual layout and probably also for landscape details in his distinctive style, and there is greater emphasis on the wild landscapes through which the emperor travelled than is the case in other monumental interpretations of southern expeditions. However, another work by Wang Hui in this volume, Reclusive scenes among streams and mountains (cat. item 250),(Figs.13 &14) painted in 1702, was intended not for the court but for a private individual named Cai Qi. Murck notes that, while Wang Hui states in an inscription on his work that he was evoking the Yuan dynasty master Wang Meng (c. 1308-1385), 'the tribute was as much conceptual as stylistic', because the work exemplifies Wang Hui's 'mature style' that blends half a dozen sources.  Fig.13 Wang Hui, Reclusive scenes among streams and mountains (first detail) handscroll, ink and colour on paper, Palace Museum, 32.7 x 296.4 cm, cat. no. 250, pp.328-9  Fig.14 Wang Hui, Reclusive scenes among streams and mountains (second detail) handscroll, ink and colour on paper, Palace Museum, 32.7 x 296.4 cm, cat. no. 250, pp.328-9 As Gerald Holzwarth describes in 'The Qianlong Emperor as art patron and the formation of the collections of the Palace Museum, Beijing' (pp.41-53), Qianlong played a valuable role in cataloguing the palace's collection of masterpieces of calligraphy and painting. Qianlong initiated the compilation of the catalogues that remain definitive reference works describing the imperial painting collection to the present day. In 1744-45, the catalogue included calligraphy and paintings with religious subject-matter in Bidian zhulin and secular works in Shiqu baoji. In 1793, a supplement (xubian) was produced for each part of this catalogue. Although the death of the Qianlong Emperor in 1799 coincided with the dramatic downturn in the prosperity of the Qing, his successor, the Jiaqing Emperor (r.1796-1820) oversaw the compilation, in 1815-1816, of a further supplement (sanbian) of the catalogue. In 1911, however, the Qing dynasty did come to an end, and over the first half of the 20th century, the Forbidden City which had housed the Qing emperors made the gradual transition from palace to museum. In 1916, after the failure of the brief attempt by Yuan Shikai to restore the dynastic system, Baoyun Lou, the Italianate villa Yuan constructed in 1915 inside the Forbidden City as his official residence, served as a site for collecting and sorting the objects left in the Qing palace. The catalogue of paintings and calligraphy produced there, titled Baoyun Lou shuhua lu, eerily forms a further supplement in the cataloguing enterprise initiated by the Qianlong Emperor more than one and a half centuries earlier. [BGD/ © Bruce Gordon Doar] |