|

|||||||||

|

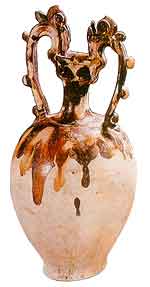

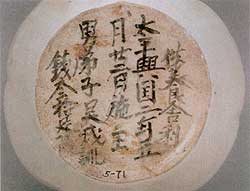

NEW SCHOLARSHIPBOOK REVIEWWang Guangyao, Zhongguo gudai guanyao zhidu (China's ancient system of official kilns), preface by Quan Kuishan, Beijing: Zijincheng Chubanshe, 2004, 214 pp., 101 sets of colour photographs, 6 black and white line drawings, 2 tables Fig. 1 Cover of Wang Guangyao, China's Ancient System of Official Kilns Many chapters in the history of Chinese pottery and porcelain technologies have been revised or rewritten over the past two decades in the light of discoveries and advances in ceramics archaeology. Recent finds of ancient ceramics in Xi'an, for example, have resulted in a modification of the history of Tang dynasty sancai (tricolour) porcelain firing (see Fig. 2), while the discovery of porcelain ritual musical instruments in a tomb at Hongshan near Wuxi in 2004 have necessitated that the invention of proto-celadon be dated several centuries earlier than previously known, to the Spring and Autumn period (722-481 BCE). The discovery in 1996 of the Tiger's Cave kiln site in Hangzhou (see Fig. 3), discussed at length in this book, has renewed study and debate regarding the Xiuneisi and other official kiln sites of the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279).  Fig. 2 Sancai pot with a bowl-shaped mouth and double-dragon handles unearthed from tomb no. 4 at Guanlin, Luoyang, Henan Over the past twenty years, archaeological work has focused on the technical aspects of kiln firing, as well as on the delineation of kiln systems. The increasing sophistication of our knowledge of the location of production centres has resulted in a heightened awareness of the economic, social and ecological impact of the ceramics industry in ancient China. Finds of Chinese ceramics also serve as evidence of an international trading system that predated the European rise to a position of global hegemony from the late 15th century onwards. Archaeological finds now also enable us to appreciate better the role Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province (see Figs. 4 and 5), as a ceramics production centre, played in a Chinese proto-industrial revolution which took place during the Ming and Qing dynasties.  Fig. 3 Saggers with Phagspa inscriptions unearthed from the late-Yuan dynasty layer at the Tiger's Cave kiln site in Hangzhou Archaeologists have also been better able to identify specific ceramic types and better understand how various wares—for example blue and white porcelain (Fig. 6) or red and green porcelain—emerged in terms of the technical advances they represented and in light of a more complex picture of kiln systems in China. These archaeological advances have been made by scholars from archaeological institutes and museums across China, as well as by scholars from Peking University and other educational institutes, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute of Archaeology in Beijing and the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Silicate Studies in Shanghai. Possessing a vast collection of ancient ceramic items, the Palace Museum is also a major centre of ancient ceramic studies, but its contribution to the field will also be enhanced by its recent establishment of an ancient ceramics research institute, as well as by the installation of new laboratories, and the preparation of its enormous collection of shards for scientific investigation.  Fig. 4 Shards of the Yongle reign (1403-1424) period unearthed at the Yuyao site at Jingdezhen Wang Guangyao, a scholar at the Palace Museum, has made important contributions to our increasingly complex and nuanced understanding of ancient Chinese kiln systems, and especially imperial kilns. A PhD graduate of the Department of Archaeology of Peking University in 1979, Wang Guangyao's work epitomises the firm grasp of scientific and historical methods, combined with a facility in interpreting ancient texts that draws together the disparate fields of archaeology (kaogu) and material history (wenwu) together in a way that enables them to contribute to social history. This is a characteristic of contemporary ceramics archaeology in China. This recently book includes many of Wang's previously published articles related to the theme of 'official kilns' (guanyao), sometimes updated and re-organised, and presents these within a context provided by a prefatory essay which is one of the most succinct and clear accounts to date of the role 'official' kilns played throughout Chinese history.  Fig. 5 Underglaze red stem bowl with Yongle reign period (1403-24) mark (unearthed at the Yuyao site at Jingdezhen) Many previous studies have focused only on the Ming and Qing dynasties, reflecting the tastes of collectors and the obsession of historians with grand and imperial traditions. Only in the Ming and Qing dynasties does the term 'imperial kiln' (yuyao) emerge to take its place beside the notions of 'civilian kilns' (minyao) and 'official kilns' (guanyao) into which Chinese ceramic production can be classified prior to the Ming dynasty.  Fig. 6 Blue and white bowl with design of linghua sprays and Xuande period (1426-35) reign mark (collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing) References to officials responsible for overseeing ceramics production occur in the earliest Chinese texts. Lüshi chunqiu, Zuo zhuan, Zhou li and Shi ji contain passages which include the titles of such officials (taozheng, taoren and fangren) and place them not merely in the Western Zhou period, but even earlier in the disputed period of the 'sage-kings'. No ceramic artefacts bearing inscriptions that detail production provenance from the pre-Qin period have been found to date. The earliest extant pottery piece that must have been produced by an official kiln is an inscribed measuring jar of the Qin dynasty, which provides evidence of the standardised system of weights and measures introduced throughout China by that first unifying dynasty. It is also generally believed that the technical uniformity of the terracotta figures that form the burial attendants of China's first emperor, Qin Shihuang, could only have been achieved by government-run ceramic workshops. Coercion, rather than patronage, would probably underscore the organisation of official kilns in this early period.  Fig. 7 Glazed ceramic bricks from the balustrade of a staircase in the courtyard of the Qianqing Gong (Hall of Celestial Purity), Forbidden City, Beijing A clearer picture of the official institutions and organisations that controlled or oversaw ceramic production in the Han dynasty is provided by inscriptions found on unearthed ceramic items, as well as by handed down texts. In the Western Han dynasty, the central government not only appointed officials to oversee salt production (called yanguan) and iron manufacturing (tieguan), but other officials to oversee and control handicraft manufactures who bore the titles zhiguan (literally 'weaving officials'), gongguan ('artisan officials') and kaogongling. The crucial aspect of the work of the kaogongling was ensuring that the government retained control over weapons production, but the 'portfolio' of the kaogongling extended to include textile production and 'the sundry crafts' (zagong). By the time of the Eastern Han dynasty, texts record the emergence of 'officials responsible for taxing handicrafts' (called zhugongshuiwu), signalling that a 'private sector' of handicraft work was being brought within the domain of officialdom or had attracted official recognition.  Fig. 8 Guan mark incorporated in the inscription on the base of a white porcelain bowl unearthed from the crypt of the Jingzhi Temple, Dingzhou From the Western Jin dynasty (265-316) through to the Jin dynasty (1115-1234), the central government's management of handicraft manufacturing saw the transition from the traditional gongguan system to one in which officials acted as 'inspectors' and 'managers' operating under the auspices of an overseeing state institution named the Zhenguan-shu (Inspection and Management Office). The Zhenguan-shu was not only responsible for overseeing the observation of ritual conventions in the production of funerary items, but was also responsible for the direct management of ceramic firing and production. Historical documents record the existence of an institution in the Liao (907-1125) and Northern Song (960-1127) dynasties termed the Ciyao-wu (Porcelain Kiln Office), the officials of which managed ceramic production at various kiln sites. After the Mongol-led armies conquered southern China, the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) established the Fuliang Ciju (Fuliang Porcelain Bureau) at Jingdezhen, which was directly entrusted with porcelain manufacturing. Fifty years after its establishment, the Ming government also set up a special organisation in Jingdezhen to manufacture porcelain primarily for official use, and this institution was long referred to as the 'official kiln' (guanyao). The Qing government established an official kiln at Mentougou in Beijing for producing ceramic tiles and architectural fittings used by the government (Fig. 7), and this too was designated guanyao or more precisely the 'guanliuli-yao' (official glaze kiln).  Fig. 9 Blue and white prunus vase of the Yongle reign period (1403-1424) of the Ming dynasty bearing the inscription 'Neifu' (Imperial Household) Apart from the above-mentioned kilns under the control of the central government, official kilns could also come under the jurisdiction of regional and local governments. Representative of this latter category are the Xuanzhou-guanyao and Runzhou-guanyao of the Song dynasty, named for the prefectural governments which ran them. Official kilns could also be named for the government construction projects for which the kilns produced ceramics, for example, the Ming dynasty's Dingling guanyao, which produced architectural components for the Ding imperial mausoleum located north-west of Beijing. Apart from ceramics, one late Qing guanyao in Qinzhou, Guangxi, also produced zisha ceramic wares that bore the seal 'Qinzhou guanyao'.  Fig. 10 Large vase produced by the Ming dynasty imperial kiln, Yuqi-yao (front) (collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing) For a long period of time the official kilns monopolised new techniques of production and gave direction to porcelain production overall. One of the major characteristics of official kilns was their supervision of the dimensions and shapes of the wares they produced. Ancient works lack a systematic nomenclature for dealing with ceramics, but it is quite clear from inscriptions on some excavated ceramics that the pieces conformed to official patterns and designs. Wang Guangyao has researched the implications and significance of these inscriptions, and several essays in this work address problems of interpreting them. There is controversy, for example, surrounding the chronologically simultaneous appearance in the period from the late Tang to the mid-late Northern Song dynasty of white glaze wares bearing the inscriptions guan or xinguan.(Fig. 8) It is quite clear from the discovery of such wares at sites which include the crypts of pagodas and the tombs of eminent officials that these were not wares made and reserved for the exclusive use of the royal family. Examples of porcelain from this period bearing the character guan have even been discovered by archaeologists in Egypt and Korea, indicating that these pieces could also be export wares not intended for royal use. The question of the significance of the porcelain bearing the marks guan or xinguan has been was examined in detail by Wang Guangyao's teacher, Quan Kuishan of Peking University who, in an article published in 1999, wrote: "I believe that the guan formulation is earlier than the xinguan mark, and that they both served to distinguish two separate batches of porcelain commissioned by the Banquets Office or by earlier or later Court Provisioners of the same office".[1] However, Wang concludes in an article first published in 2001 and included in this volume that the inscriptions on these wares refer instead to official porcelain shapes and designs (guanyang) that were subject to official taxes. He also points out that, from the Northern Song period onwards, the names of particular organs of the central government, for example Shangshi-ju (Court Banqueting Bureau), Shangyao-ju (Court Medicine Bureau) and Shu-fu (Household Office), appear as inscriptions on porcelain. Similarly, the term Neifu (Palace Household) also appears on wares in the Yuan and early Ming dynasties. (Fig. 9) Wang regards these wares as falling within the scope of 'official porcelain', but the majority of these were sold commercially, unlike 'imperial wares'. Wang Guangyao makes it quite clear that the official kilns are not to be identified as 'imperial kilns' (yuyao), a term only appropriate for specific institutions of the Ming and Qing dynasties. The imperial kiln of the Ming dynasty was termed Yuqi-chang,(Fig. 10) while that of the Qing was the Yuyao-chang.(Figs. 11 and 12) The Ming dynasty Yuqi-chang was established in the 1st year of the Xuande reign (1426) and, although it was created on the basis of the guanyao system, it was not the logical result of the development of the official kiln system, but was, according to Wang Guangyao "an outcome of the strengthening of autocratic rule by Zhu Yuanzhang, Emperor Taizu of the Ming dynasty, effected during the struggle for the succession by his descendant Emperor Xuanzong in order to further strengthen imperial authority".[2] The yuyao constituted a new system within the official kiln system because it facilitated direct control by the emperor over porcelain production, and court officials were now sent to the kilns to supervise the manufacture of ceramics in person. Henceforth, the production of imperial porcelain became an integral system not previously seen and wholly different from the management of 'tribute porcelain' to be found in the Tang and Song dynasties.  Fig. 11 Blue and white porcelain circular table-top inset made at the Qing dynasty imperial porcelain workshop, Yuyao-chang (collection of the Capital Museum, Beijing) Tribute wares had been produced at kilns in Henan-fu, Yuezhou, Xingzhou, Yaozhou, Dingzhou and Raozhou, but the term jingong ('presented as tribute'), as applied to the wares from these kilns, refers to a taxation arrangement governing their production, as well as to political and ritual criteria that the government stipulated the wares of these kilns must fulfil in order to qualify for consideration as tribute wares. At Yuandan (Chinese New Year), for example, 'tribute porcelain' would be displayed at the court together with other tributes, including those from abroad, by either the Hubu (Household Board) or the Libu (Board of Ritual). An imperial regulation of 1007 made it permissible to sell a proportion of these wares. It is evident from this that tribute wares were not necessarily the exclusive property of the throne, unlike imperial ware under the Ming and Qing dynasties. It was not even permissible for civilian kilns to copy the types of wares produced by the latter imperial kilns; infringements attracted harsh penalties. In this study, however, Wang Guangyao, perhaps over-emphasizes the role of official kilns in China's ceramic history. While it might be true that official kilns often monopolised innovation, this did not necessarily mean that works commissioned, for example, by the yuyao were perforce innovative. In fact, the reverse is often true. Wang Guangyao should himself be well aware of this. In an article published in 1999 in Gugong Bowuyuan yuankan and not included in this collection, Wang discussed the penchant of the Qianlong Emperor for commissioning handicrafts that saw masterpieces in one medium translated to other media. In that article, Wang discussed the replication of an ancient ritual bronze food vessel known for its inscription as the 'Ban gui' in porcelain. This aesthetically dubious and unoriginal effort entailed the participation of the Painting Workshop under the Imperial Household Department and the Qianlong Imperial Kiln. Fulfilling the commission did, perhaps, result in the creation of an 'ancient bronze glaze' for use on ceramic replicas of bronzes, but the job suggests the squandering and deployment of valuable resources at a time when the imperial kiln at Jingdezhen was at its height under the competent directorship of the innovative Tang Ying.  Fig. 12 Blue and white censer with cloud and dragon design made during the reign of the Shunzhi emperor (r. 1638-1661) at the Qing Yuyao-chang kiln (collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing) It should also be pointed out that the imperial kilns did not monopolise innovations in the production of export wares either. It is widely argued that the development of blue and white porcelain was probably influenced by pottery tastes of the Middle East, as much as it depended on earlier breakthroughs in underglaze technology in China. The improvements in blue and white wares were sustained by the evolution of a large export market in the Middle East and then later in Europe. Innovative blue and white porcelain items were not produced exclusively by official kilns; most of the Ming and Qing dynasty originality in both narrative and illustrated blue and white pieces was, in fact, initiated by civilian kilns addressing market demand. Nevertheless, Wang Guangyao makes it clear that the ceramics traditions of China unfolded through a bifurcation between official and civilian kilns, and it is clear that state involvement in the development of metallurgy and of many handicrafts in China was significant from an early date. The control that the Ming and Qing courts exercised over handicraft production stands in dramatic contrast to the guild-based organisation of handicrafts in contemporary Europe, as do the nature, degree and scale of government and imperial patronage of arts and handicrafts in China. The fourteen essays comprising this book represent a multi-faceted attempt to shed light on the official and imperial kilns in different periods. Hopefully, this volume will inspire other scholars to document various aspects of China's official kiln system and turn the spotlight on the civilian kilns and the social and economic systems that sustained them. [BGD] Notes:[1] Quan Kuishan, 'Guanyu Tang-Song ciqi shang de guan he xinguan zikuan wenti in China Ancient Ceramics Research Society ed., Zhongguo gu taoci yanjiu, no. 5, November 1999, pp. 222-29; tr. by B. G. Doar under title 'The phantom official kiln: Guan and xinguan marks on Tang and Song porcelain', China Archaeology and Art Digest, Hong Kong, June 2000, pp. 95-106. [2] Wang Guangyao, Zhongguo gudai guanyao zhidu, p.18. |