|

||||||||||

|

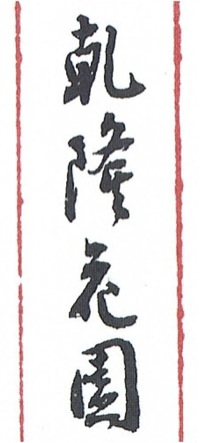

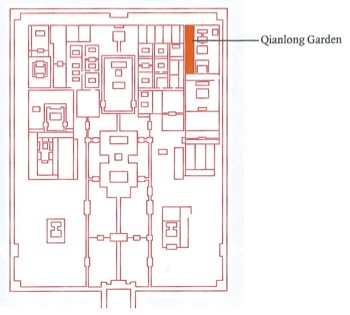

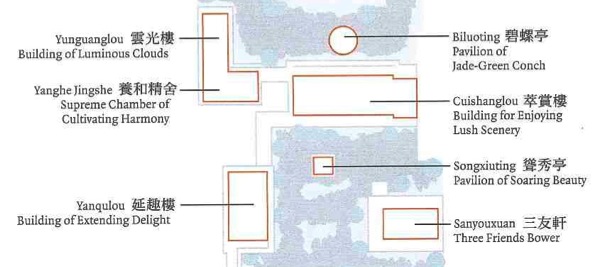

NEW SCHOLARSHIPA Note on the 'Qianlong Garden' 乾隆花園Geremie R. Barmé and Sang Ye 桑曄 Fig.1 'Qianlong Garden' (Qianlong Huayuan) in the hand of Ma Heng, Director, Palace Museum, from a diary entry dated 31 October 1949. Source: Gugong Bowu Yuan, ed., The Manuscript of Ma Heng's Diary (Ma Heng riji shougao 馬衡日記手稿), Beijing: Zijincheng Chubanshe, 2005, vol.1, p.188. When did the series of connected gardens and pavilions along the western flank of the Ningshou Gong 寧壽宮, or the precinct in the Forbidden City built ostensibly as a retirement palace for the Qianlong Emperor, become known as the 'Qianlong Garden' (Qianlong Huayuan 乾隆花園)? First, what does the Qianlong Garden, which is the focus of the exhibition 'The Emperor's Private Paradise' (see 'A Sylvan Symposium', also in this section) encompass? A short-hand account offers the following: The Qianlong Garden in the Forbidden City was designed as a private, two-acre garden retreat with four courtyards, elaborate rockeries, and some 27 pavilions and structures. The garden was largely abandoned after the last emperor left the Forbidden City in 1924….[1] In her exhaustive catalogue essay, 'The Qianlong Garden in the Palace of Tranquility and Longevity', the curator of the exhibition 'The Emperor's Private Paradise' Nancy Berliner offers a meticulous study of the courtyards, features, buildings and designs that make up the garden.[2] From readily available materials it can be established that the expression—what in Chinese is called a 'popular appellation' (sucheng 俗稱), 'Qianlong Garden'—was already in general currency among conservators and scholars during the last mainland years of the Republic of China. For instance, in a diary entry dated 31 October 1949, Ma Heng 馬衡, Director of the Palace Museum (Gugong Bowu Yuan 故宫博物院) at the time, notes that a Survey Group had been established and that, among other things, it was undertaking a detailed study of the Qianlong Garden.[Fig.1] It was planned that a restoration of the multiple-courtyard garden area was a priority for the museum. Needless to say, events, including what would become the evanescent political demands of the new regime, overtook these optimistic plans.[3] Also in 1950, the architectural historian Lu Sheng 盧繩 lead a team from the Architecture Department of Tianjin University to survey both the Forbidden City and the Thirteen Ming Tombs using modern measuring equipment. In the materials related to this undertaken published in 1957 Lu used the expression 'Qianlong Garden' to describe the gardens of the Ningshou Gong Palace complex.[4]  Fig.2 The site of the Qianlong Garden complex within the Forbidden City. Source: Nancy Berliner et al, The Emperor's Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City, New Haven and London: Peabody Essex Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2010, p.95. When the Palace Museum journal, Gugong Bowu Yuan Yuankan 故宫博物院院刊, began publishing again in 1979 after the demise of the Cultural Revolution, it was common to see the Qianlong Garden referred to in its pages. In 1980 alone that journal published Yu Zhuoyun 于倬雲 and Fu Lianxing's 傅連興 'The Garden Design of the Qianlong Garden',[5] and Fu Lianzhong's 傅連仲 'Miscellanea Regarding the Qianlong Garden'.[6] It is noteworthy that originally the Studio of the Quiet Heart (Jingxin Zhai 靜心齋, also known as 鏡清齋) in Beihai 北海, part of the Lake Palaces within the Imperial City and which lie along the western flank of the Forbidden City, reconstructed in 1758, was known as the 'Small Qianlong Garden' (Qianlong Xiao Huayuan 乾隆小花園). Although it was frequented by and beloved of the Empress Dowager Cixi 慈禧 in the late-nineteenth century, it was not called 'Cixi's Garden', nor for that matter did the Ningshou Gong complex, which Cixi used extensively during the last, often dramatic, years of her life, subsequently become known as 'Cixi's Garden'.[7] Just as odium and obliquity can explain the reasons for this, equally fame, stature and imperial success can explain why Qianlong's name lies heavily over so many sites.  Fig.3 Detailed map of the Qianlong Garden. Source: Nancy Berliner et al, The Emperor's Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City, New Haven and London: Peabody Essex Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2010, p.95. Click on the map for a more detailed image.

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes:[1] From the World Monuments Fund website: http://www.wmf.org/project/juanqinzhai-qianlong-garden. There is an added statement that after 1924 the Qianlong Garden 'buildings were never opened to the public.' We would suggest that this requires further research. In the context of the gardens, see also Nancy Berliner, ed., Juanqinzhai in the Qianlong Garden: The Forbidden City, Scala Publishers, 2009. Writing for the official Palace Museum website (see: http://www.dpm.org.cn/shtml/116/@/17802.html) Yang Wengai 杨文概 defines the Ningshou Gong Garden in the following way: 宁寿宫花园位于宁寿宫后区西路。乾隆三十七年(1772年)至四十一年(1776年)改建宁寿宫时,在后区西部南北长160m,东西宽约40m的窄长地段内建成一座花园,以备乾隆皇帝归政后游赏,故又称乾隆花园。 宁寿宫花园南北分隔成四进院落,每一院的布局各具特色。 第一进院主体建筑为古华轩,轩前一株古楸树,轩因此得名。轩东山峦上有承露台,轩西为凿有流杯渠的禊赏亭,亭北山上有旭辉庭。轩南有假山,其间有曲径。轩东南角有曲廊、矩亭、抑斋围成的小院,院内东南堆砌假山,山上小亭名'撷芳亭'。 古华轩后垂花门内即第二进院。正房遂初堂,东西有配房,转角廊、倒座廊将正房、配房、垂花门联为一体,是个典型的三合院。院中湖石点景,花木三五。 遂初堂后第三院以山景为主。院中峰峦起伏,山间有深谷,山下有隧洞通向四方。上山有蹬道,山上有天桥,耸秀亭屹立山顶。院北有萃赏楼,西有延趣楼,东南麓有座北面南的三友轩,三面出廊,东面紧靠乐寿堂西廊。 萃赏楼北是花园最后一院。主体建筑符望阁,阁南山屏之上建有碧螺亭,其造型设计及装修均采用5瓣梅花形或折枝梅花纹。亭南有小虹桥通萃赏楼。山屏西南养和精舍平面为曲尺形。阁西有玉粹轩,阁北有倦勤斋,玉粹轩北依西墙有小楼竹香馆,外围一道南北向弓形矮墙。倦勤斋南、玉粹轩北接有爬山廊,可达竹香馆二层。 宁寿宫花园布局十分得体,山石树木、亭台楼阁经营有绪。屋顶类型力求变化,色彩丰富,有黄、绿、蓝、紫、翠蓝等色,梁枋彩绘大量使用了金线苏式彩画。中轴线布置有变化,后半部轴线略东移。整座花园既有私家园林玲珑秀巧的风貌,又与皇宫华贵富丽的氛围相协调。 [2] See Nancy Berliner with Mark C. Elliott and Liu Chang, Yuan Hongqi, and Henry Tzu Ng, The Emperor's Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City, New Haven and London: Peabody Essex Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2010, pp.94-193. [3] See Gugong Bowu Yuan, ed., The Manuscript of Ma Heng's Diary (Ma Heng riji shougao 馬衡日記手稿), Beijing: Zijincheng Chubanshe, 2005, 2 vols, vol.1, p.188, see also the entry for 21 March 1950, vol.1, p.255. The recent Director of the Palace Museum, Zheng Xinmiao 鄭欣淼, also mentions this in a commemorative essay about Ma Heng. See Zheng, 'Outstanding achievement and lustrous virtue—commemorating Mr Ma Heng fifty years after his death' (Jue gong shen wei qi de yong xin—jinian Ma Heng xiansheng shishi 50 zhounian 厥功甚偉其德永馨—紀念馬衡先生逝世50週年), in Gugong Bowu Yuan yuankan, 2005:2. [4] See Lu Sheng, 'The Qianlong Garden of the Former Palace in Beijing' (Beijing Gugong Qianlong Huayuan 北京故宮乾隆花園), Materials Office of the Cultural Relics Bureau of the Ministry of Culture, ed., Cultural Relics Reference Materials (Wenwu Cankao Ziliao 文物參考資料), 1957:6. Further to this, other materials related to Lu Sheng's work can be found in Lu Sheng's Researches into Traditional Chinese Architecture (Lu Sheng yu Zhongguo gujianzhu yanjiu 卢绳与中国古建筑研究), a posthumous multi-volume collection published in 2007 by Zhishi Chanquan Chubanshe. In particular see, 'The Qianlong Garden of the Former Palace in Beijing', Chapter 7 in the volume Notes on Researches into Traditional Chinese Garden Design (Zhongguo gudian yuanlin yishu yanjiu zhaji 中國古典園林藝術札記), as well as the first collection of diaries titled '1953 Diary of a Survey Research Group in Beijing' (Beijing canguan cehui shixituan riji 1953 nian 北京參觀測繪實習團日記1953年).

[5] 于倬雲、 傅連興,《乾隆花園的造園藝術》 ,故宮博物院院刊 ,1980年第3期,3-11頁. [6] 傅連仲,《乾隆花園點滴》, 故宮博物院院刊 ,1980年第4期91-94頁. [7] See Berliner et al, The Emperor's Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City pp.202-205. |