|

||||||||||

|

NEW SCHOLARSHIPParadise Regained?Duncan M. CampbellA Review of Vera Schwarcz, Place and Memory in the Singing Crane Garden, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, 260pp., with photographs, maps and illustrations.

Yixin 奕訢 (Prince Gong 恭親王)

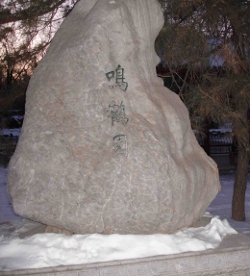

The Chinese garden, Vera Schwarcz reminds us in this beautifully crafted study, ‘…demands discrimination (and often privileged education and leisure time) for the slow-paced unfolding of [its] carefully constructed vistas and cultural symbols’ (p.20). Here Schwarcz, the noted historian of, in particular, the iconoclastic May Fourth Movement of 1919 and its various legacies (see, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 18, June 2009), sets herself the task of undertaking the slow-paced excavation of the layers of cultural memory that underlie a particular Chinese site.  Fig.1 A map of the Garden of Yan (Yan Yuan 燕園), the campus of Yenching University, the site of Peking University since the 1950s. The former garden mansions, Minghe Yuan, Jingchun Yuan and Langrun Yuan are clearly marked. The Unnamed Lake is visible on the lower right-hand side, and Shao Yuan in the lower left-hand corner. (Official map of the Peking University campus, 2008.) Click on the map for a more detailed image. The site is the present campus of Peking University in the northwest Haidian (海淀 , literally ‘Shallow Sea’) district of metropolitan Beijing.[2] It is a campus that Schwarcz knows well, but she tells us that her book is occasioned by the unexpected sight, when out for a stroll around the campus one October Shabbat morning in 1993, of the then only recently opened Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology.  Fig.2 Taihu stone engraved with the name Minghe Yuan 鳴鶴園. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010)

Schwarcz starts her guided tour of this site at the Pavilion of Winged Eaves (Yiran ting 翼然亭), which she first explored with her son in 1989 and which was at the time in a state of some considerable delapidation. Returning to the pavilion a decade later, Schwarcz finds it now renamed and much restored. It sports an official plaque reading (in Schwarcz’s translation): ‘XIAO JING TING 校景亭—SCHOOL SCENES PAVILION: The original name of the School Scenes Pavilion was Yi Ran Ting, which was part of the Singing Crane Garden refurbished in 1926 after the founding of Yenjing University when it was decorated with ten famous spots of Yenjing University—hence its name of “School Scenes Pavilion”. This name was retained during the restoration that begun in 1984’.(p.9) In the following chapters, Schwarcz explores the silences in the official truncated and selective account of the history of the pavilion, and to this end, in an approach that she outlines in her introduction (‘A Garden Made of Language and Time’), she is influenced by the work of the doyens of garden history in both China and the West, the late Chen Congzhou 陳從周 (1918-2000) and John Dixon Hunt respectively, as well as by the great historical geographer Hou Renzhi 候仁之(b. 1924), also of Peking University. From Chen Congzhou, Schwarcz adopts the celebrated distinction between ‘stillness’ (jing 靜) and ‘motion’ (dong 動) as mutually interrelated elements of both traditional garden design in China and the experience of a Chinese garden.[3] In Greater Perfections: The Practice of Garden Theory (2000), John Dixon Hunt argues that gardens are best understood as ‘… both a physical object and a place experienced by a subject.…the idea of a garden is at the same time paradoxically composed of perceptions of gardens in many different ways and different people and different cultures and periods.‘ It is an approach that similarly, underpins Schwarcz’s work.[4] In the case of Hou Renzhi, Schwarcz had the very considerable privilege of access both to some of his unpublished writings as well as to the historian himself as guide around the campus.  Fig.4 The Unnamed Lake with the water tower (Boya Ta 博雅塔) in the distance. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010) In each of her five chapters, Schwarcz deals with a particular phase or episode in the history of the site. She begins her story, in medias res so to speak, with an account of the garden that the Pavilion of Winged Eaves once graced and which is celebrated in the fifty illustrations of the red-crowned cranes (grus japonisis) that decorate its ceiling: the Singing Crane Garden (Ming He Yuan 鳴鶴園) built by Mianyu 綿愉 (Prince Hui 惠郡王; 1814-65), fifth son of the Jiaqing emperor (1760-1820; r.1796-1820) and brother of the Daoguang emperor (1782-1850; r.1821-51). After a brief glimpse at the exquisite late-Ming garden that once stood on the site, Ladle Garden (Shao Yuan 勺園 ), a garden commemorated in the name of the university’s modern foreign student and visitor dormitory complex,[5] Schwarcz focuses her attention in her first chapter on the extraordinary engagement with this district on the part Manchu élite, the newly installed rulers of an ever expanding Chinese empire. Crucial in this connection, as in so many other areas of Chinese cultural life, is the role of the Qianlong emperor (1711-99; r.1736-95)[6] and his embellishment of the Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanming Yuan 圓明園) created during the life of his imperial father, the Yongzheng emperor (see China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 8, December 2006, which was devoted to this garden).[7] From the first the model for the gardens that would proliferate in the district from the Ming dynasty was the scenery of the south. Visiting Mi Wanzhong’s 米萬鍾 Ladle Garden, his fellow examination candidate Wang Siren 王思任 (1575-1646), a native of Shaoxing, wrote: ‘Dreaming of River South, I find myself already there’ (meng dao Jiangnan zhen yi dao 夢到江南真已到).  Fig.5 Langrun Yuan 朗潤園. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010) Following the death of the Qianlong emperor and the downfall of his corrupt favourite Heshen 和珅 (1750-99),[8] the former bodyguard’s Gentle Spring Garden (Shuchun Yuan 淑春園), built in extravagant and improper imitation of the emperor’s own demesne which lay nearby to the north, was divided up between the children of the new emperor. Heshen’s marble boat stands still tethered to the banks of the university’s Unnamed Lake (Weiming Hu 未名湖), ‘mute witness to the history that unfolded in this corner of China’(p.55). We can gain some vicarious idea of the lingering splendour of the Manchu gardens of Haidian with their ‘skilled blending of Manchu moralism and Confucian aesthetics’ (p.59) from the account of a stroll through Yixin’s Garden of Moonlit Fertility (Langrun Yuan 朗潤園) by the American traveller Dorothy Graham. Schwarcz quotes at length from Graham’s Chinese Gardens: Gardens of the Contemporary Scene, an Account of Their Design and Symbolism, the earliest English-language monograph on the topic of the Chinese garden: Trees fringing the lakes have their trunks obliquely set, to lead the eyes’ focal point, across the water. Pools of shadow rest within pools, imparting depth and mystery. The foliage is green upon green, the darker leaves making a foil for the light. It seems that the garden has come into being without the volition of man. Yet, to realize the astuteness of the designer, one has only to look beyond its walls to where the barren steppes stretch to the whirling dust clouds raised by files of camels. From a desert, a stylized forest has been made. Within the high outer walls, a series of connecting hills was piled to shut out all sight of the world, and all sound…. This is the perfection of the ideal: hills to stimulate the imagination, still water conducive to calm…. Height is balanced by depth; the stark stones are enfolded by pliant verdue. It is a place of utter lonliness. The soul escapes the ebb and flow of emotion to merge with the mystic quietude(p.72).  Fig.6 A path to the west of Langrun Yuan. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010) Graham had visited in the 1930s. Tragically, as treated in Schwarcz’s next chapter (‘War Invades the Garden’), those high walls had not proved high enough to shut out all sight and sound of the world beyond. Relying on a variety of eyewitness European accounts, Schwarcz relates the story of the sacking of the Garden of Perfect Brightness and its surrounding gardens in late October 1860 by British and French troops, as revenge for the torture and killing of twenty European prisoners. Before the fires were lit, Robert Swinhoe, translator to both James Bruce, the eigth Lord Elgin, and General Hope Grant, a man who was later to write of the ‘mournful pleasure’ of the sight of the flames engulfing the palaces, paused just long enough to look about and note that: ‘The variety of the picturesque was endless, and charming in the extreme; indeed, all that is most lovely in Chinese scenery, where art contrives to cheat the rude attempts of nature into the bewitching, seemed all associated in these delightful grounds’ (p.100). ‘The mind replays last year’s stage,/ all that flourished, shimmered,/ now swallowed by red flames/ a gnarled pine my sole companion’, wrote (in Schwarcz’s translation) Yihuan 奕環 (Prince Chun 醇親王; 1840-91), half-brother to Yixin and father of the Guangxu 光緒 emperor (1871-1908; r.1875-1908), ‘The ravaged garden/ is not my wound,/ rather a generation born/ into a misshapen world’(pp.110-11).[9] Schwarcz’s third chapter, ‘Consciousness in the Dark Earth’, takes up the history of the Singing Crane Garden (then known as the Korean Garden as it was under lease from a descendant of Mianyu to a Korean man as a place to graze his dairy cows) upon its acquisition in 1920, after protrcted negotiations, by John Leighton Stuart (1876-1962) to serve as the campus for Yenching University. The architect now charged with the task of ‘rehabilitating’ the gardens of old in this new and very different context, the American Henry Murphy, consciously (and concienciously) engaged with the architectural history of his site: ‘The more deeply I get into the beauty, richness and dignity of the best of the old buildings that have come down to us from the great Chinese builders of the past, the more certain I am that it is worth all the time and trouble and expense we are putting into our efforts to translate this wonderful art from mere archaeology into the living architecture of today, and so to preserve to the Chinese, and to the world, their splendid heritage’, he wrote as his project neared its end (p.136).[10] Schwarcz’s fourth chapter, ‘Red Terror on the Site of Ming He Yuan’, as its title suggests, provides the yin side of the yang (both 陽 and 洋) story told in the previous chapter. After ‘Liberation’ in 1949, the consolidation and relocation of all the institutes of higher learning in the capital saw Peking University take over the Haidian campus of Yenching. And it was here on this campus, of course, that the first of the Big-character Posters that heralded the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution appeared in late May 1966, posted by a number of rebellious academics including Nie Yuanzi 聶元梓, a junior member of the university’s Philosophy Department. By late August, the campus was already aflame with violence. On one day alone during that month, over 200 people were either killed or wounded. In keeping with the 1 June editorial in the People’s Daily of that year, entitled ‘Sweep away all freaks, ox-monsters, and snake spirits’ (Hengsao yiqie niugui sheshen 横掃一切牛鬼蛇神), numerous Peking University luminaries were incarcerated in ‘Ox Pens’ (niupeng 牛棚). The voice that Schwarcz listens to most closely for an understanding of this phase of the history of the site is that of the late scholar of Sanskrit, Ji Xianlin 季羨林 (1911-2009), from his Recollections from the Ox Pen (Niupeng zayi 牛棚雜憶), in particular. English readers can now access a larger amount of Ji’s celebrated memoir than Schwarcz has room for here, Chapters 13-16 having been made available on the web in the translation of McComas Taylor of the Australian National University, working with Ye Shaoyong 葉少勇 of Peking University. With the advantage of hindsight, Ji says, presumably tongue-in-cheek: Eight huge characters were daubed in white paint on the south-facing wall of one of the out-buildings in the yard: ‘Sweep away all cow-demons and snake-spirits’. Each character was taller than a man. The calligraphy was exquisite, ‘like dragons flying and phoenixes dancing’, and gave full expression to its author’s skill. Suddenly the whole compound was filled with splendour, and moreover, it had more than enough power to overawe a group of ‘cow-demons and snake-spirits’ like us. This was much more impressive than even a hundred harangues from guards holding spears. Speaking personally, I deeply appreciated those eight words. I felt happy just looking at them. I personally believe their author should be added to the historical register of great Chinese calligraphers. This leads me to reflect on the fact that, during the ‘Cultural Revolution’, writing big-character posters improved calligraphy, beating people strengthened the writs, ‘struggling’ improved one’s abilities in sophistry and dissembling, and fighting instilled courage. We should always consider matters in terms of both positives and negatives—can we really claim that nothing good ever came out of that disastrous decade?’ (‘Life in the Cattle Yard’, p.4) Like all good traditional Chinese garden accounts, Schwarcz’s last substantive chapter takes us back to where we started our tour of the campus with her, the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology. In this respect too, the story is a tourtuous one; although the letter of intent to build the museum had been signed in 1985, the Beijing Massacre of 1989 delayed the project. After belaboured negotiations over almost every aspect of the design and naming of the building, the museum, designed by Lo Yi Chan 陳璋源, son of the eminent scholar of Confucian philosophy, Wing-tsit Chan 陳榮捷, was finally opened in May 1992, some years after Sackler’s death. Schwarcz raises only to dismiss the image of this collector of Chinese art as ‘a greedy, vulgar multimillionaire’. ‘I collect as a biologist’, Sackler told an interviewer in 1986, ‘To understand a civilization, a society, you must have a large enough corpus of data’. That the collection held in this museum, including a fragment of the famous Chu silk manuscript, has been returned to a China that fifty years ago was intent upon destroying all such traces of the past, is nonetheless something to be celebrated.  Fig.7 Minghe Yuan with the Sackler Museum in the background. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010) This, then is the story of a lovely garden (‘Throughout the garden, willowy stones and grand buildings conveyed a sense of elegance and serenity’, in the words of its owner) that is built on the site of an earlier and equally splendid garden; of a garden that is then destroyed in an act of extreme cultural vandalism but which, half a century later, becomes a university campus; of a university campus that, four decades later, is the epicentre, again, of a maelstrom of violence directed at everything that the gardens of old embodied, but which, finally in this telling, hosts a museum dedicated to the preservation, study, and display of some of the material remains of China’s earliest antiquity. My summary here of Schwarcz’s various chapters masks the extent to which the various phases of her account of this extraordinary site are woven together seamlessly, and also the extent to which the story is charged with her own engagement with place and with memory over the course of her scholarly life. As Schwarcz argues in the opening pages of this poetic account, ‘Gardens are not merely earthly stuff. They occupy grounds in the mind as well. Some reach there by the beauty of their design, some by the power of their cultural symbolism. Many use both. Other gardens take up no space at all. Yet even as ruins, or as memories of ruins, they have the power to breath life into worn words. They create spaciousness in dark times’(p.1).  Fig.8 Taihu stone engraved with the name Langrun Yuan. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010) Returning to Peking University a year or so ago, I reflected that in the thirty-odd years since I first visited the universiy in 1976, I had never seen the campus looking so exquisitely (and expensively) manicured. Does this present state of the campus represent the ‘new birth’ anticipated so long ago by Yihuan, in a poem written in 1880s shortly after touring the ruins of his once splendid garden: Twenty autumns later, again the garden, the archery field silent, broken pavilions, dance halls abandoned, a sea of shards, new birth perhaps from rubbleSadly, I suspect not, for the aesthetic and intellectual freedom to roam unfettered wherever one wished afforded by the gardens of old are no longer available to the students and faculty of the contemporary university. In allowing us to see beyond the present and meretricious veneer of this particular and layered site, Schwarcz has given those mute shards a voice that will serve to remind us of both its former glories and its past terrors. Notes:[1] This is Vera Schwarcz’s translation of this poem, composed by Yixin (1833-1898) sometime in the late 1880s-early 1890s, after he had been dismissed from office and had retreated to his Garden of Moonlit Fertility in Haidian, as found on pp.74-75 of the book under review. On Yixin, sixth son of the Xuantong emperor (1782-1850) and better known in the West by his title Prince Gong, see also Arthur W. Hummel, Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period (1644-1912), Washington: Government Printing Office, 1943 (hereafter ECCP), pp.380-84. [2] The Dijing jingwu lüe 帝京景物略 (Brief Guide to the Sights and Features of the Imperial Capital), compiled by Liu Tong 劉侗 (d.1636) and Yu Yizheng 于奕正 (d. 1635) and first published in 1635, notes: ‘In districts proximate to the capital, wherever a spring happens to flow, there are to be found gardens and pavilions, from ancient times down to the present, each of which change their name whenever taken possession of by a new owner, although the flow of the spring that occasions the gardens never itself changes’ (近都邑而一流泉古今園亭之矣一園亭主易一園亭名泉流不易也), for which, see Dijing jingwu lüe, Beijing: Beijing guji chubanshe, 1982, p.213. When speaking of Haidian specifically, an area once blessed with a dense network of surface and subterranean rivers, streams, and springs, this work tells us that: ‘Taking the road to the south one comes upon an incline and the bridge surmounting the incline soars higher that the roofs of the surrounding buildings. Standing upon this bridge and gazing out in the direction of the gardens one can see nothing but an expanse of water, the surface of which is covered entirely by lotus flowers, all of which are white in colour’ (路而南陂焉陂上橋高於屋橋上望園一方皆水也水皆蓮蓮皆以白).(p.218) Early in her study, Schwarcz says of the district: ‘What Haidian had to offer was what garden builders needed the most: water. Called “liquid delight”, this was the essential prerequisite for landscape design.... Without water, nothing grew. With water, it was not only trees and flowers that flourished. It was also the contemplative mind that drew sustenance here from vistas of liquid stillness. Skilfully channelled waterfalls and carefully crafted fishponds became the hallmarks of Haidian’.(pp.42-43) [3] For which, most influentially, see Chen Congzhou, On Chinese Gardens, Shanghai: Tongji University Press, 1984. For an excellent engagement with this work, see Stanilaus Fung, ‘Movement and Stillness in Ming Writings on Gardens’, in Michel Conan, ed., Landscape Design and the Experience of Motion, Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2003, pp.243-62. [4] John Dixon Hunt has returned to this theme of the reception history of gardens more recently in his The Afterlife of Gardens, London: Reaktion Books, 2004. He concludes: ‘It is surely clear that as historical sites extend their lives into later periods with changed cultural conditions, the original configuration and its meanings are “modified in the guts of the living”; (to recall Auden’s celebration of the afterlife of Yeats’s poetry). The issue, then, is how we allow those modifications into our historical readings of sites as well as—where relevant—into our physical reformulations of those that continue to exist but that, given the inherent transience of garden art, need preservation or conservation’.(p.196) [5] The history of this garden, built between 1612-14 and visited by some of the leading lights of the dynasty’s literary and artistic world, has been beautifully recreated by Philip K. Hu, in his ‘The Shao Garden of Mi Wanzhong (1570-1628): Revisiting a Late Ming Landscape through Visual and Literary Sources’, Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, 19, 3/4 (1999): 314-42. For a reproduction of Mi Wanzhong’s ink and colour handscroll depiction of his garden (Shao Yuan xiu xi tu 勺園修禊圖), rediscovered in the 1930s in the collection of a Tientsin family and now in the possession of Peking University Library, see William Hung 洪業, ed., The Mi Garden (Shao Yuan tu lu kao 勺園圖錄考), Harvard-Yenching Institute Sinological Series, 1933; rpt. Taipei: Chinese Materials and Research Aids Service Center, 1966, a reference inexplicably absent from the bibliography of the book under review. [6] For a recent full-length treatment of this man, see Mark C. Elliott, Emperor Qianlong: Son of Heaven, Man of the World, New York: Longman, 2009. [7] In this case, too, Schwarcz is indebted to a wonderfully evocative treatment of this most remarkable of imperial gardens: Geremie Barmé, ‘The Garden of Perfect Brightness: A Life in Ruins’, East Asian History, 11 (1996): 111-58. Elsewhere, Schwarcz footnotes her indebtedness to Geremie Barmé’s guidance around the gardens of Haidian, and thanks him for the use of some of his photographs in her earlier treatment of this topic, ‘Garden and Museum: The Shadows of Memory at Peking University’, East Asian History, 17 (1999): 169-92. The present author, in his turn, is grateful to Geremie Barmé for the more recent photographs of the campus that grace this review. Readers of Schwarcz’s book need to be warned: in the bibliography, this reference and many others (such as to Philip Hu’s article) perpetrates numerous errors. The many instances of carelessness throughout the main text of Schwarcz’s book (of reference, romanisation, dating and so on) do not however serve to detract too significantly from this book’s very real value as both a work of scholarship and as a humanistic engagement with the issues of place, memory and heritage in contemporary China. [8] For a short English-language biography of this man, by Knight Biggerstaff, see ECCP, pp.288-91. [9] On Yihuan, see Fang Chao-ying’s biography in ECCP, pp.384-86. [10] In her account of this phase of the history of the site, Schwarcz is indebted to the work of Tang Keyang, ‘From Ruined Gardens to Yan Yuan—A Transformed Vision of the “Chinese Garden”: A Discussion of Henry K. Murphy’s Yenching University Campus Planning’, Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, 24, 2 (2004): 150-72. |