NEW SCHOLARSHIP

Orchid Pavilion: An Anthology of Literary Representations | China Heritage Quarterly

Orchid Pavilion: An Anthology of Literary Representations

Duncan M. Campbell

The following translation, with prefatory note, introduces a new project in Chinese literary history related to place, memory and commemoration. Although a project in the making, Duncan Campbell's work on the Orchid Pavilion shows how many of the themes of this issue of China Heritage Quarterly—place, time, cycles, commemoration and memory—are also important to an understanding of the mental landscape of writers in dynastic, and indeed pre-dynastic times. In this regard, see Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys), 'The Chinese Attitude Towards the Past', carried in the virtual pages of Issue 14 (June 2008) of this journal under Articles. A better understanding of such ways of remembering and evoking the past, through literary artefact and cultural symbol, also provide us with insights into the powerful drag of traditional forms for making meaning as they resonate in the modern Chinese world. A future issue of China Heritage Quarterly will be devoted to the Orchid Pavilion and its place in Chinese cultural history from the time of Wang Xizhi to that of Mao Zedong.—The Editor

But I fear that as the years slip by one after the other even the mountains and rivers rise and fall; as one age gives over to the next, it is only with brush and ink that we can seek to preserve our melancholy.

—Zhang Dai 張岱, 'Guichou lanting xiuxi xi' 癸丑蘭亭修禊檄 [A Summons to Undertake the Spring Lustration Ceremony on the Occasion of the Guichou cyclical Anniversary][1]

Memory takes root in the concrete, in spaces, gestures, images, and objects; history binds itself strictly to temporal continuities, to progressions and to relations between things. Memory is absolute, while history can only conceive the relative.

—Pierre Nora, 'Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire'[2]

The past was a past of words, not of stones... Chinese civilization seems not to have regarded its history as violated or abused when the historic monuments collapsed or burned, as long as those could be replaced or restored, and their functions regained... The only truly enduring embodiments of the eternal human moments are the literary ones.

—Frederick Mote, 'A Millennium of Chinese Urban History: Form, Time, and Space Concepts in Soochow'[3]

Twice during his long life, in 1613 and then again in 1673, the late-Ming dynasty historian and essayist Zhang Dai (1597-?1689) visited the site of Orchid Pavilion (Lanting 蘭亭), some eleven kilometers south-west of Guiji 會稽 (present-day Shaoxing 紹興; Guiji is now pronounced Huiji, although another reading is Kuaiji) in Zhejiang Province, to mark the occasion of the cyclical anniversary of that day in 353 when Wang Xizhi 王羲之 (309-c.365), the greatest of Chinese calligraphers, wrote his 'Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Poems' (Lanting ji xu).

It had been here that, during the late spring of the Ninth Year of the Everlasting Harmony (Yonghe) reign period of the Eastern Jin dynasty (i.e., 353 CE), Wang Xizhi had gathered forty-one of his friends and relatives (including his son, Wang Xianzhi 王獻之, 344-88) in order to undertake the Spring Lustration Ceremony, one whereby the evil vapours of the winter past were washed away in the eastward flowing waters. Twenty-six of the men named as being present produced between them a total of thirty-seven poems, and towards the end of the day, we are told, Wang Xizhi, formerly employed in the Imperial Library but then serving in Guiji as the General of the Army on the Right (youjun 右軍), wrote his immortal preface to this collection, on 'cocoon paper' with a 'weasel-whisker brush', in 324 characters and 28 columns.

Wang Xizhi's Lanting ji xu [Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection] as translated by H.C. Chang reads:

In the ninth year [353] of the Yonghe [Everlasting Harmony] reign, which was a guichou year, early in the final month of spring, we gathered at Orchid Pavilion in Shanyin in Guiji for the ceremony of purification. Young and old congregated, and there was a throng of men of distinction. Surrounding the pavilion were high hills with lofty peaks, luxuriant woods and tall bamboos. There was, moreover, a swirling, splashing stream, wonderfully clear, which curved round it like a ribbon, so that we seated ourselves along it in a drinking game, in which cups of wine were set afloat and drifted to those who sat downstream. The occasion was not heightened by the presence of musicians. Nevertheless, what with drinking and the composing of verses, we conversed in whole-hearted freedom, entering fully into one another's feelings. The day was fine, the air clear, and a gentle breeze regaled us, so that on looking up we responded to the vastness of the universe, and on bending down were struck by the manifold riches of the earth. And as our eyes wandered from object to object, so out hearts, too, rambled with them. Indeed, for the eye as well as the ear, it was pure delight! What perfect bliss! For in men's associations with one another in their journey through life, some draw upon their inner resources and find satisfaction in a closeted conversation with a friend, but others, led by their inclinations, abandon themselves without constraint to diverse interests and pursuits, oblivious of their physical existence. Their choice may be infinitely varied even as their temperament will range from the serene to the irascible. Yet, when absorbed by what they are engaged in, they are for the moment pleased with themselves and, in their self-satisfaction, forget that old age is at hand. But when eventually they tire of what had so engrossed them, their feelings will have altered with their circumstances; and, of a sudden, complacency gives way to regret. What previously had gratified them is now a thing of the past, which itself is cause for lament. Besides, although the span of men's lives may be longer or shorter, all must end in death. And, as has been said by the ancients, birth and death are momentous events. What an agonizing thought! In reading the compositions of earlier men, I have tried to trace the causes of their melancholy, which too often are the same as those that affect myself. And I have then confronted the book with a deep sigh, without, however, being able to reconcile myself to it all. But this much I do know: it is idle to pretend that life and death are equal states, and foolish to claim that a youth cut off in his prime has led the protracted life of a centenarian. For men of a later age will look upon our time as we look upon earlier ages—a chastening reflection. And so I have listed those present on this occasion and transcribed their verses. Even when circumstances have changed and men inhabit a different world, it will still be the same causes that induce the mood of melancholy attendant on poetical composition. Perhaps some reader of the future will be moved by the sentiments expressed in this preface.[See Note 7 below]

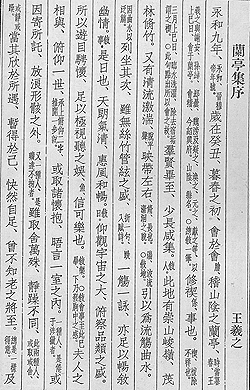

The text of Wang Xizhi's 'Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection' from

Guwen guanzhi, a famous Qing-dynasty anthology of literary prose (late seventeenth century).

Zhang Dai's 1673 account of his two pilgrimages to the ancient site, translated below, is an anxious one: where now were those 'high hills with lofty peaks, luxuriant woods and tall bamboos', the 'swirling, splashing stream' both described in that text and depicted in later rubbings of the scene that day, rubbings that Zhang Dai has spent his life 'visiting in spirit'? Why the discrepancy between text and image and the desolate scene that greeted his eyes?

As a site, Orchid Pavilion combines both the temporal and spatial aspects of the term commonly used, both traditionally and in contemporary parlance, to refer to important historical sites—mingsheng guji 名勝古跡, that is, sites famous for their surpassing beauty and where linger the traces of antiquity. In later representations, both literary and pictorial, the occasion served to define a particular set of social and aesthetic ideals: a refined and sophisticated elegance juxtaposed with suggestions of the social and political decadence that inevitably results from such an excess of insouciance and self-absorption. It is a style that to Chinese eyes found its most influential literary expression in a single book, Liu Yiqing's 劉義慶 (403-44) Shishuo xinyu 世說新語 [A New Account of Tales of the World], produced in the early 430s, the sixth century commentary to which preserved an important recension of the text of Wang Xizhi's 'Preface'.

Although Wang Xizhi's 'Preface' and the manner in which it was written have occasioned an enormous wealth of scholarship, both traditional and contemporary, the site itself and its vicissitudes over time has been relatively neglected in scholarly discussions. The study of its literary representations at the hands of late-imperial visitors such as Zhang Dai, however, encompassing an anthology of translations of related material, both literary and historical, will contribute to a burgeoning scholarship on aspects of elite travel during the late imperial period and the associated poetics of place in China, the often conflicting imperatives of memory and of history, the relationship between landscape and memory, the creation of local (and later, national) identities, and the preservation over time of sites of cultural and historical importance, and to aspects of late imperial Chinese travel. This translation is offered as a first contribution to this end.

On the True Site of the Orchid Pavilion of Antiquity

Zhang Dai

張岱:古蘭亭辨[4]

Guiji's fine hills and streams find no parallel throughout the empire, and when the evening mists settle or the morning clouds begin to lift, their beauty seems to gather especially along the Shanyin Road.[5] Thus it is that one encounters sites of surpassing beauty and famous mountains at every turn. Little wonder then that when Wang Xizhi, the General of the Army on the Right, was searching for a place to serve as his residence, from amongst the 'thousand cliffs' and 'ten thousand torrents'[6] found here he chose only that patch of land where Orchid Pavilion stood. The lustrous beauty of the scenery and its various features would doubtless have been unmatched throughout the ages. As a youth, moreover, whenever I viewed ink engravings of Orchid Pavilion, depicting the marvellous steepness of the surrounding cliffs and peaks, the lofty height of the pavilion and the gazebo, the meander with its flowing wine cups, the bathing geese and the inkstones being washed, as I began to unfurl the scrolls, I would be unable to prevent myself from visiting the place in spirit.

In the

Guichou year of the reign of the Wanli Emperor [1613], when I was in my seventeenth year, as it happened to be the cyclical anniversary of the year in which the General of the Army on the Right had undertaken the Spring Lustration Ceremony, I persuaded some friends to accompany me on a visit to the site.[7] When we arrived at a spot to the left of the Heavenly Pattern Monastery we came across some ruined foundations and discarded stone slabs and were told that this was the site of the Orchid Pavilion of antiquity. I stood transfixed and wide-eyed; the bamboo, the rocks, the brook and the hills—none of these seemed at all worthy of note. The scene as it appeared now before me was a world away from that depicted in the engravings of the site. Devastated, I choked and sobbed for a long while. For this reason, one must seek to prevent any unconventional travellers who desire to come here from doing so, in order thereby to preserve Orchid Pavilion's reputation. Thus it was that I bound my feet and did not dare come here again, and another sixty years have gone by.

This year is again a Guichou year [1673], the twenty-second such year since the Ninth Year of the Everlasting Harmony reign period [353]. How blessed I have been to have twice experienced this anniversary. As an expression of my good fortune, I wrote a Summons to my like-minded friends to forgather at Orchid Pavilion on the Third Day of the Third Month, in imitation of the Spring Lustration Ceremony of old. The day dawned bright and clear and taking my brother Bi along with me, light-hearted and in pursuit of surpassing beauty, we traversed ridges and ascended cliffs. Sitting in the abbot's room of Heavenly Pattern Monastery, we sought out rubbings taken from ancient stelae. It was only after reading these that we became aware of the fact that both the Orchid Pavilion of antiquity and the former Heavenly Pattern Monastery had been consumed by flames at the end of the Yuan dynasty, the actual site of their foundations having been completely lost to memory. The pavilion that at present bears the name 'Orchid Pavilion' was in fact constructed in the twenty-seventh year of the reign of the Yongle Emperor [1429] on a site chosen by a man surnamed Shen, then serving as the Prefect of the area.[8] Because the site encompassed two ponds, the pavilion had been constructed above these ponds and stones had been laid to form a water-course into which water from the fields had been led in imitation of the meander with its flowing wine cups—this last done in an especially childish manner. Here, those 'high hills' had been rejected, the 'tall bamboos' pushed aside, the prevailing order seemed clumsy in the extreme, the scene one of desolation—little more than a solitary thatched hut placed in the midst of the surrounding paddy fields. Moreover, the site was constricted, whilst the pavilion and the gazebo were mean and dirty; if it had been here that those forty-two men to be seen in the various depictions of the scene that day were to have gathered, then, with their canopied carriages and their numerous retainers, where would they have found purchase on this 'wart' or 'crossbow pellet'?[9] That the whole thing was no more than a counterfeit was patently obvious.

An illustration of the Orchid Pavilion from Linqing's

Tracks in the Snow, mid nineteenth century.

The monks confirmed that this was not in fact the original site and that half a li away there stood the ruins the Orchid Pavilion of antiquity. Bi and I hastened through the brambles, impatient to view the site. When we got there, however, we discovered that, constricted and out-of-the-way, as a site it seemed to have even less to recommend it. Standing to the side of the site was a stone gate upon which had been engraved the words 'Orchid Pavilion of Antiquity'. When I examined this inscription carefully, I discovered that this gate actually marked the start of the old road leading towards Orchid Pavilion, not the site of the pavilion itself. We returned to the abbot's room and continued our investigations by consulting the rubbing of the inscription written by Shang of the Ministry of Personnel.[10] This document informed us that in the Third Year of the reign of the Wanli Emperor [1575], Liu Jianhao and Wang Songbing, both of Western Sichuan, along with others, obtained this piece of land at the foot of the 'high hills' where bubbled the source of the meander, and thinking that it retained something of the appearance of the Eternal Harmony reign period of old, they collected subscriptions and entrusted the monks with the restoration of the pavilion. There stood a pavilion, 'its wings outspread'[11], its plaque reading: 'Former Site of Orchid Pavilion'. Later on, five halls were constructed, to accommodate the banquets of visitors to the site. Before long, however, the monastery again fell into a state of dilapidation and the pavilion too soon lay in ruins, even its site no longer susceptible to inquiry.

![The Orchid Pavilion stele at the Orchid Pavilion Park at Kuaiji Shan outside Shaoxing, March 2009. [Photo: GRB]](017/_pix/Final-Pix1.jpg)

The Orchid Pavilion stele at the Orchid Pavilion Park at Kuaiji Shan outside Shaoxing, March 2009. [Photo: GRB]

Turning to Bi, I said: 'The General of the Army on the Right was a man of culture, a man of exquisite refinement. Surely the site that he selected for his pavilion would offer some sort of prospect! Why ever are we combing this site in search of it, here where the grass grows wild and the trees are so dense?' Soon thereafter we came across a patch of level ground in front of the Heavenly Pattern Monastery and here at last were the 'high hills with lofty peaks' spoken about by the General of the Army on the Right, the 'swirling, splashing stream, wonderfully clear', the 'luxuriant woods and tall bamboos', here where the hills encircled us like a screen and the stream held us in its embrace. Waving his arms, Bi shouted: 'This is it, this is it!' Thereupon we laid out our felt rugs upon the ground, loosened our belts and remained there spread-eagled for a considerable time, entranced by the scene. It was late afternoon before we returned.

![Wang Youjun Temple, the Orchid Pavilion Park, March 2009. [Photo: GRB]](017/_pix/Final-Pix2.jpg)

Wang Youjun Temple, the Orchid Pavilion Park, March 2009. [Photo: GRB]

For a thousand years now I believe that the true site of Orchid Pavilion of antiquity has been lost, like the authentic version of Wang Xizhi's preface itself, which Biancai treasured more than his own life and which he preserved wrapped beneath ten layers of silk cloth, not allowing it to be viewed by anyone else. Later on, Xiao Yi tricked Biancai out of it, but as he hastened back to the court with it, he stole a glance at it hidden in his sleeve and flowers began to bloom everywhere. This, anyway, is the story of it told in the monastery. My burning desire now is to build a thatched pavilion here in order to return to the pavilion it's original site. To do so would be to speak up on behalf of Orchid Pavilion and to restore a modicum of dignity to the General of the Army on the Right. Just as was the case with the 'Orchid Pavilion Preface' that lay hidden in the rafters before Xiao Yi managed to get hold of it, my brother and I have managed to trick the pavilion itself back into existence. This pavilion, once built, will be named 'Ink Blossom', in allusion to the story of Xiao Yi.[12]

Notes:

[1] Yun Gao, ed., Langhuan wenji [Paradise Collection] (Changsha: Yuelu shushe, 1985), p.114.

[2] Representations, 26 (1989):9.

[3] Rice University Studies, 59.4 (1973):51.

[4] In Yun Gao, ed., Langhuan wenji, pp. 119-21. As in the past, I am grateful for the care with which my colleague Stephen McDowall has read earlier drafts of this translation and for his suggested readings.

[5] The Shanyin Circuit, the area surrounding present-day Shaoxing in Zhejiang Province, was noted for its natural beauty. This opinion was most famously expressed by Wang Xizhi's (309-c.365) son, Wang Xianzhi (344-88), as recorded in the 'Speech and Conversation' chapter of A New Account of Tales of the World: 'Whenever I travel by the Shanyin road, the hills and streams complement each other in such a way that I can't begin to describe them'. See Richard B. Mather, trans., Shih-shuo Hsin-yü: A New Account of Tales of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1976), pp.71-2; romanisation altered.

[6] Again in the 'Speech and Conversation' chapter of the Shishuo xinyu, we are told that: 'When [the artist] Gu Kaizhi [ca.345-406] returned to Jiangling from Guiji, people asked him about the beauty of its hills and streams. Gu replied, "A thousand cliffs competed to stand tall,/ Ten thousand torrents vied in flowing./ Grasses and trees obsured the heights,/ Like vapors raising misty shrouds"'. From Mather, Shih-shuo Hsin-yü, p.70; romanisation altered.

[7] In H.C. Chang, trans., Chinese Literature: Volume Two: Nature Poetry, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1977), pp.8-9 (romanisation altered, translations of the reign title and pavilion name added).

[8] Other accounts of the history of the site suggest that this date should read the Twenty-seventh Year of the reign of the Jiajing emperor (1548).

[9] An allusion to Yu Xin's (513-81) 'Ai Jiangnan fu' [Rhapsody on River South], for which see William T. Graham Jr., 'The Lament for the South': Yu Hsin's 'Ai Chiang-nan fu' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), pp. 90-91. In Graham's translation, this section of the poem reads: 'Now, territory reduced to a wart,/ With a fortress like a crossbow pellet,/ His enemies bitter,/ His alliances cold,/ This vengeful bird could fill up no sea;/ This simple old man could move no mountains.'

[10] This may be a reference to Shang Tingshi (1497-1584), a native of Guiji and a man whose biography had been written by Zhang Dai's great-grandfather Zhang Yuanbian (1538-88).

[11] An expression found in Ouyang Xiu's (1007-1072) 'Zuiwenting ji' [An Account of the Pavilion of the Drunken Old Man], a translation of which may be found in Stephen Owen, ed. & trans., An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), pp.613-14.

[12] Legends associated with the manuscript are recorded in a variety of Song dynasty sources; Zhang Dai himself provides a retelling of some of this material in his Shi que [History's Lacunae] (1824; Taipei: Huashi chubanshe, 1977), vol.1, pp.346-50.