|

|||||||||||

|

FEATURESOn ShanghaiThe Terrible CityT.K. Chuan 全增嘏

This essay appeared in The China Critic, III:39 (17 July 1930): 682-683.—The Editor

Related ArticlesA Hymn to Shanghai, by Lin Yutang 林語堂

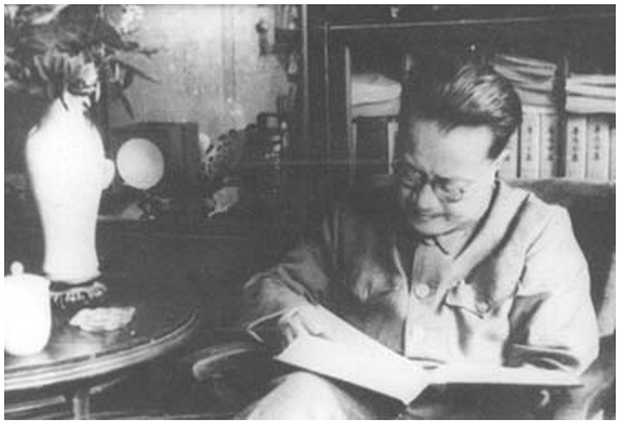

Apropos of The 'Shanghai Man', by Ch'ien Chung-shu 錢鍾書 A New Shanghai, The China Critic Those who have seen Massenet's opera Thais will remember Athanael, the Cenobite monk, who left his desert hermitage avowedly to save the soul of a gilded and wanton dancer in Alexandria. For seven days and nights, he traveled along the left bank of Nilus, and when he finally saw from the summit of a hill the mighty City of Serapis, glittering in the rosy-fingered dawn, he could no longer contain himself, and raising his lusty tenor voice, he sang that famous aria beginning; 'Voila donc la terrible cité!' To call Shanghai the terrible city, to compare her with Ptolemaic Alexandria may seem to some to be an odious task, yet if one should adopt the Spengierian standpoint, no inquiry could be more fruitful and fascinating. A word or two about Spengler would not be amiss here. According to the author of 'Der Untergang des Abendland,' every civilization has its spring of hope and its winter of despair. The Classical civilization, for instance, which was abloom in Periclean Greece, died ever since Alexander made his conquests. It dies and was no more. So with the Magian or Arabian, the Faustian or Germanic civilizations—they arose, flourished and passed away. The Western civilization too, so it seems, is on the verge of decline and may soon be supplanted by a new or yet unborn culture. Civilizations therefore follow the cycle of eternal recurrence, and none may escape from the grim necessity of alternate rise and fall. It follows also that history does repeat itself and it is meaningless to divide it into the Ancient, the Mediaeval and the Modern. There cannot be an arbitrarily chosen time axis. Chronologically speaking, Pythagoras antedated Cromwell, the Battle of Platea happened centuries before the Battle of Tours, Socrates taught in Athens long before Goethe held his literary court in Weimar, Savonarola preached and pillaged in Renaissance Florence while Mussolini rules with his fasces in twentieth century Rome—yet considered morphologically, they are all contemporaneous characters or events. Such, in brief, is Spengler's thesis.  Fig.1 T.K. Chuan 全增嘏 (1907-1984)

To take up once more our original discussion, Shanghai of today and Alexandria of the Hellenistic times have really many points in common that one cannot help from noticing. To begin with, both are cosmopolitan or to use Spengler's word, Megalopolitan cities. Strabo, the Greek geographer who lived in the first century A.D., told us that on the streets of Alexandria, one would encounter 'Ethiopians, Troglodytes, Persians, Medians, Hebrews, Arabs, Syrians, Parthians,' not mentioning of course Greeks, the native Egyptians and the half-breeds. For the division of Shanghai into the International Settlement, the French Concession and the Chinese city, we have the corresponding quarters in Alexandra: the Jewry, the Brucheum where the Greeks dwelled and the Rhacotics or the Egyptian city. The dominating people in Alexandria were naturally the Greeks, and for a Jew or an Egyptian not to speak the Greek language at all was considered a shame; just as one would in Shanghai today hear bespectacled youths from missionary colleges and returned students from England or America proudly holding forth, sometimes rather lamentably, in the King's English. Most probably, they would address each other as Toms and Dicks, just as the Egyptians in Alexandria sometimes would answer to the names of Phillipos or Agathon. Human nature has indeed been always the same. Furthermore, both Alexandria and Shanghai are commercial and industrial cities. To quote Gibbon who wrote in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: 'The lucrative trade of Arabia and India flowed through the port of Alexandria to the capital and provinces of the empire. Idleness was unknown. Some were employed in blowing of glass, others in weaving of linen, others again manufacturing the papyrus. Either sex, and every age, was engaged in the pursuit of industry, nor did even the blind or the lame want occupations suited to their conditions.' It is needless to point out that Shanghai too has its foreign trade, its child and woman laborers and its blind, or pseudo-blind, fortune-tellers. Speaking of amusements, Alexandria boasted of 400 theaters, (cf. Eutychius Annal, ii 716) and although Shanghai has not more than a hundred, no other Chinese city can nearly come up to the same mark. The cry of 'Panem et circenses' has its echo in the modern version: 'Rice-bowls and grey-hound races!' The sing-song girls are the counterpart of the hetaira. True, the former are not as cultivated as their ancient sisters of joy who could recite glibly from Sophocles and Euripides, yet no one can say that they are any less voluptuous and pulchritudinous. Like prostitutes, like poets and philosophers. The 'failure of nerve' which characterized the literary and philosophic products of the Hellenistic Alexandria is truly descriptive of the state of letters in contemporary China, with Shanghai as its center. One finds everywhere advocates and preachers of mysticism, sensualism, skepticism, estheticism. Proletarianism, etc, etc, which are all variant forms of the search for certainty in an age of doubt and disturbance. Tons of books are being turned out annually by third-rate men, which are imitated by the fourth rate and read by the fifth rate. A friend of ours who is an expert statistician told us that if we piled up the books published in Shanghai last year in the London Museum, they would crowd out all the other books that had already been there. He made one mistake. The London Museum would be too good a place for them! The comparison between the two cities however cannot be carried too far; and Spengler notwithstanding, we are convinced that it has to stop somewhere. For instance, culturally Shanghai is nil, while Alexandria, with her famous Museum and Library, was the center of learning and research. Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy, Hipparchus—these are names to conjure with, and who, who indeed, of the scientists in Shanghai today can we mention in the same breath as they? Again, Alexandrians were noted for their gentleness of manner, but in Shanghai one meets daily bores and bullies by the dozens. Civilities nowadays are considered superfluous and the cultivation of life's amenities has become a lost art, what with your imported gospels of efficiency, excitement and strenuous living. Indeed like another Athanael, we too wish to sing a hymn of hate and condemnation with however this difference: Athanael hated Alexandria for her science, her gentleness and her beauty; but we hate Shanghai for her ignorance, her unmannered-liness and her lack of beauty. Alexandria was only morally decadent but Shanghai is intellectually and culturally decadent as well. The conclusion is obvious. Civilizations rise and fail, empires wax and wane, perhaps only in voluminous treaties written by learned doctors and paranoiac prophets, but this much we are sure: Shanghai is a terrible city! |