|

|||||||||||

|

FEATURESOn Japan'Easterkuo' Comes into BeingGordon Fan

This article appeared in The China Critic, XX:12 (12 March 1938): 139-140.—The Editor

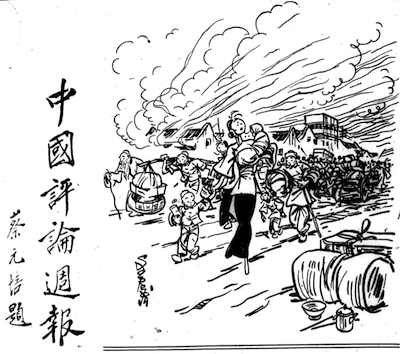

Related ArticlesJapan's Status in Shantung, by D.K. Lieu 劉大鈞 The Little Critic's Peace Plan, by T.K. Chuan 全增嘏 Carl Crow Speaks for China, The China Critic A Glimpse of the Japanese Mind, by T.D. Gen Mental Differences between Chinese and Japanese, by 'Reflector' Austria's German name is Oesterreich, that is, the country (Reich) toward the east (Osten). Since the time of its emergence from the old Eastmark in the twelfth century until three hundred years ago it constituted for Mediaeval Europe the border against the 'East', the last bulwark against 'Asia'. Upon the walls of Vienna and provincial ramparts broke successive waves of invaders: the Avares, who have disappeared; the Madgyars, who settled in the Danube Basin and formed Hungary; the Turks who twice attempted and failed to take Vienna by storm. Only last year Austria's capital celebrated the 300th anniversary of its second siege when it was valiantly defended by a Prince von Starhemberg … People by Germanic settlers who absorbed the Alpine tribes, Austria under the rule of the Hapsburg dynasty extended its sway over neighboring, non-German territories and eventually became the dual-monarchy, Austria-Hungary. The phenomenal expansion in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was characterized by a historian with the remark: Belli gerant alii; tu, Felix Austria, nube! ('Others may make wars; you, Happy Austria, marry!') Because since the end of the thirteenth century the Hapsburgs held, until 1806, also the crown of the Holy Roman Empire, Austria (but not Hungary) was part of the Reich, which broke up formally under the impact of the armies of Napoleon I. In that year even the nominal rule which the Emperor of Austria had exercised over the German princes ceased. In 1870, marking Prussia's final hegemony, the constitution of the new (the second) imperial Germany left the Hapsburg domains definitely out.  Fig.1 Sapajou draws the evacuation of Shanghai, cover of The China Critic, 11 November 1937. The end of the war in 1918 witnessed the disrupture of the monarchy, the end of the Hapsburgs, and the reduction of Austria to six small provinces inhabited by six million German-speaking people. The new Austria was about as large as the old Eastmark but, in the modern world, too small to live, too big to die. It would have been natural, and economically advisable, to join the new German Republic. The Weimar Constitution of 1919 provided seats for two Austrian delegates—but they never came. The victors would not have it. In 1930, Austria (which had meanwhile been kept alive by international loans) and Germany announced a customs union. At once France threatened, Czechoslovakia rattled the sabre, Great Britain frowned, Mussolini 'held manoeuvres' in southern Tyrol. The matter was referred to the Hague: eight representatives of the former Allies voted against, seven neutrals and former friends of the Central Powers for, the union. With a majority of one vote it was declared a contravention of existing treaties. Meanwhile, the Wall Street boom had collapsed. Like an irresistible epidemic, the great depression spread and undermined the economic structure of the West. The Austrian Credit-Anstalt failed, precipitating a general collapse of currencies and credit; the pound went off gold, the franc slipped, the American dollar was devalued. Billions in credit were frozen in Germany. The crisis became worse. Then Hitler became Der Fuehrer. Hitler is Austria-born and educated (only in 1929 did he become a German citizen). For the first time since 1806 an Austrian ruled again the Reich, but this time not as a distant impotent emperor but as dictator with an all-powerful party. Hitler's first coup aimed at bringing Austria into the German fold. Nazi propaganda and terrorism flooded the country, culminating in the putsch in Vienna in the summer of 1934 and the assassination of the chancellor, Dollfuss. It failed. Why? Because Mussolini marched two divisions to the Brenner Pass, and the border of Tyrol, and proclaimed himself guarantor of Austrian independence. The Rome Protocols followed, marking Austria—and Hungary—allies, virtual dependencies, of Italy. During the two following years Austria and Germany were hardly on speaking terms. But Hitler compensated himself—temporarily—elsewhere. The invasion of Manchuria had revealed the impotence and disunity of the democracies. The Treaty of Versailles, already badly damaged, was torn to shreds: reparations were officially stopped, armaments undertaken on a large scale, the de-militarized Rhineland Zone occupied by German troops. There was no resistance from France or Great Britain; and Mussolini had no objection to German aggressiveness away from the Italian borders. He had other plans for which he needed German support. Early in 1936 Mussolini undertook the conquest of Ethiopia. The British fleet was concentrated in the Mediterranean while the League of Nations invoked sanctions. But Germany was not in it—over the Brenner rumbled train after train of German materials. Did Hitler support Mussolini just out of affection? Hardly. Their first meeting in Venice in 1933 had been a failure—no showman likes a rival on the stage. But Italy was after an empire and challenging the one-time Mistress of the Sea. It needed backing which only renascent, belligerent Germany could give. The Rome-Berlin axis was forged. 'Natural affinity' between two totalitarian states would not have sufficed to accomplish this result. A price, I am certain, was agreed to by Italy then, to be paid later. It has been paid now. Austria, which in the meanwhile led a fairly sheltered, hence improving but basically insecure existence, saw on 12 March German armed forces crossing the border and arriving in Vienna. Her government resigned and was replaced by Austrian Nazi officials. On 13 March Hitler made a triumphant entry into Linz, capiral of the province of Upper Austria. Austria is no more. And what is the foreign reaction this time? Great Britain accepts, France is thrown into consternation, Czechoslovakia has an attack of the jitters. The protests of London and Paris, mere matters of form, are rejected by Berlin as 'twenty years too late'. Mussolini, however, is silent. 'He had been advised one day in advance.' The union has been inevitable, I think, since 1919. But Hitler was not. He was made possible by the failure of the democracies to make room for the inevitable. It had to be forced down their throats. We are living in an era of conquests, of warring states. This is nothing new. What is new is that the world has become so small that almost any move in one place upsets the balance in another place. Europe's colonial wars in the nineteenth century hardly affected the Powers; they were conducted, as it were, 'on the side.' In the twentieth century this is no longer possible—there are no more 'primitive people' as easy prey. Abyssinia was the last one in this category, and even there the Italian conquest trespassed on the interests of another Power. On the other hand, as it has become fashionable to speak of aggression and suppression in terms of defence and 'the people', all coups, intrigues, invasions—in short, the gamut of international brigandage—are now carried out under the heading of benevolence. The vocabulary is practically identical, as if the speeches were all ready-made, like a businessman's suit to be put on for the occasion. Here are some examples of the latest hold-up. From Hitler's Manifesto, ready by Dr. Goebbels:

Dr Schuschnigg was charged with 'infringing the spirit of the Berchtesgaden Agreement' (of which nothing except meaningless generalities about 'complete understanding' etc. were published. Actually, the Chancellor was put through the third degree, a new law in international manners). President Miklas was requested to resign 'because his functions are incompatible with the present situation in Austria.' From Hitler's letter to Mussolini: 'My action in Austria is only to be regarded as an act of legitimate national defence …' The German Ambassador in London: 'I could not suffer that 6,500,000 men of an ancient and great civilized people be submitted in practice by the nature of their government to a colonial regime …' General Goering: 'German troops entered Austria not as conquerors but as liberators. Who has the right to interfere when Germans meet Germans?' Hitler in Linz: 'I have believed in this mission, I have lived and fought for it, and now I have fulfilled it.' And so forth, ad infinitum. Do not these utterances sound strangely familiar? Have we not heard them before? Have we not read about such 'agreements'? Certainly. All we have to do is to change the proper names: for the Austrian words we substitute Manchuria, Hopei, China, Nanking, Chiang Kai-shek, the Chinese people; for the speakers' names Matsumoto, Sugiyama, Hirota, Matsui; for Berchtesgaden the Ho-Umetsu Agreement and the parallel to 1931, 1935, 1937 is complete. Germany has copied the copyists. Two more observations; of secondary importance but closely related to the above parallel:

|