|

|||||||||||

|

FEATURESThe Critic at LargeChristopher G. Rea Australian Centre on China in the World The University of British Columbia

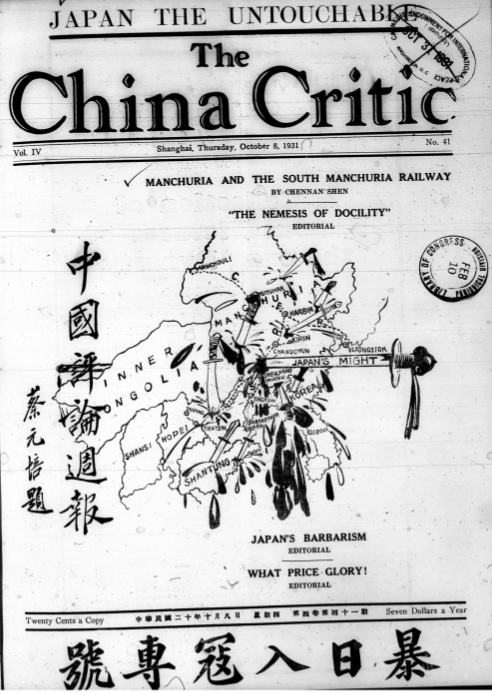

The China Critic (中國評論週報 1928-1940, 1945), among its various enterprises,could be said to have pursued a type of New Sinology 後漢學 before the fact. Its scope was comprehensive, historically-informed, and up-to-date. It strove to make all things Chinese intelligible and accessible to an English-language readership, while specializing in deep analysis through the long-form essay. It was attentive to, and commented on, current trends in Sinology, as well as journalistic and popular modes of talking about China. A glance at its contents testifies to the ambition of its coverage; its feature articles, as individual in tone as their authors, reveal an editorial standard of deep engagement with issues of importance to China and the world. Its contributors were mindful of their public role and put a premium on expressing their ideas, opinions and erudition not only clearly, but with stylistic flair. They presumed, or at least encouraged, omnivorous multilingual reading (including not just English and contemporary vernacular Chinese, but also various forms of the literary language). They promoted 'China literacy'.  Fig.1 Dutch Sinologist Jan Julius Lodewijk Duyvendak, quoted in The China Critic in an editorial commemorating the establishment of the Sinological Institute (Sinologish Instituut) at Leiden, on 26 February 1931 Most striking in The Critic's writings on culture is the sense of China's cultural heritage being a part of the lived present. The poets, essayists, dramatists, philosophers, and historians of imperial China were no musty relics of the past but companions that helped them to take pleasure in what was to be enjoyed in their own era and to think through its myriad of problems. The early Qing dynasty bon vivant Li Liweng (李笠翁, better known as Li Yu 李漁, 1610-1680), for example, was, to Lin Yutang (林語堂, 1895-1976), 'one of the finest human spirits that ever lived in China' and inspired Lin's own extensive writings on the art of living.[3] Yan-Ying Lu 盧延英 argues for 'the modernity of Confucius' teachings', including his 'ideals of democracy and cosmopolitanism' and finds in the Confucian canon 'the earliest expression of Chinese national spirit and the forerunner of modern nationalism'.[4] Quentin Pan (潘光旦, 1898-1967), as Leon Rocha notes, drew on Confucius and Mencius to validate his eugenicist theories of race. In a special issue devoted to Wang Anshi (王安石, 1021-1086), multiple editors argued for the relevance of that Song-dynasty scholar-official's political and economic thinking for contemporary China. These editors' approach to the past, in short, was at once critical and experimental, as well as being curatorial; they culled, excerpted, summarized, translated, analyzed, explained and adapted the past creatively for their pedagogical projects. Enthusiasm (whether fault-finding or favourable) animated their analysis. A comparison between the editorial enterprise and verve of The China Critic and New Sinology has, of course, its limits. For one thing, The China Critic's editors inhabited a starkly different political climate than that of China (not to mention Australia) today. War, whether in China or abroad, was ever-present and threatening. The year 1928, which marked the beginning both of The China Critic and what came to be known as the 'Nanjing Decade', inaugurated a brief period of political stability relative to the warlord era which had preceded it. It was a time that inspired confidence in civil society to attempt bold new cultural experiments, not least publishing ventures like The China Critic. Yet the period of openness was to be short-lived. The declared war with Japan that began in 1937 had a direct impact on The Critic, hardening its tone, narrowing its scope of discussion, dispersing many of its contributors, and eventually bringing about its closure. The momentum of The China Critic's New Sinology, which brought modern and cosmopolitan sensibilities to bear on ways of understanding China, was foreshortened by force. The opinions expressed in its pages resonated beyond its era, however, and its institutional precedent remains relevant to this day.  Fig.2 Australian journalist George E. Morrison. On 17 March 1932, The China Critic ran an editorial celebrating the inaugural Morrison Lecture. The approach of the editors of and writers for The Critic differs also from New Sinology in that The Critic was an institution—not a critical ethos—and a commercial one at that. It accepted advertising and paid its contributors. Though its writers had close ties with government and academia, the institution as a whole was at an entrepreneurial remove from both. New Sinology, in contrast, though its audience encompasses the realms of policy and public opinion, is a decidedly academic initiative, in addition to being an intellectual disposition. To those with an interest in Chinese history, and the abiding 'rhyming of the past with the present', The Critic rewards reading as it offers durable insights and analysis, while at the same time encapsulating the complexities of its era. It was a forum for the exchange of ideas whose participants expressed a wide spectrum of cultural and political attitudes. Indeed, a close examination of The Critic confounds nostalgia and makes it difficult to cast it as a beacon of progressivism or untrammeled free speech. As Shuang Shen 沈雙 and other scholars have noted,[5] even in its heyday of the mid-thirties, the ostensibly cosmopolitan views expressed in its pages were by no means uniformly liberal. Positions adopted by 'Critic gentlemen' on matters such as sex, race and governance could be conservative, apologistic, and even reactionary. The present issue of China Heritage Quarterly provides a selection of essays on a variety of topics to allow readers to make their own judgments. Reading these articles, however, is merely a first step toward understanding The Critic in relation to the fervid politics of its era. As Rudolf Wagner points out in his essay, The Critic was part of a complex and multilingual publishing landscape in Republican China, one whose foreign-language periodicals even today remain largely inaccessible and—both individually and in relation to their Chinese-language peers—poorly understood. Political and other differences notwithstanding, The China Critic distinguished itself as a Sinological innovator via its intense concern both with China and with criticism itself. As Qian Zhongshu's words quoted at the beginning of this essay suggests, The Critic's contributors were in the business not just of relaying facts and figures, but also—through polemics, as well as via the example of their own analysis—changing the way people talked about China. They inherited, and sought to perfect, an array of modernising attitudes toward cultural production, not least the ideals of journalistic professionalism and critical autonomy, both of which were under constant threat. Unlike some of their predecessors of the May Fourth era, they generally did not repudiate the holistic and moral model of the literati, or wenren 文人, but instead tried to modernise it, often through self-conscious efforts to integrate culture and criticism in their own occupations. Literary criticism, for example, to Qian Zhongshu was in China 'an unduly belated art', to which he later devoted most of his career.[6] One positive effect of such a sense of mission was critical ambition. Many Critic writers were 'critics at large' in so far as their interests and essays ranged across topics from aviation to publishing to philosophy to law to literature, and in all of these efforts they remained confident in their own powers of analysis and expression. Their multiple voices give the magazine a sense of personality and dynamism. But The Critic also regularly mustered its institutional clout to present a unison voice on pressing matters of concern. Again and again during its years of publication, The Critic advanced considered yet strongly worded statements of 'What We Believe' that aimed to persuade rather than harangue or sloganeer. These editorial pronouncements nevertheless were not equally embraced by all writers for The Critic. The political opinions of its contributors ran the gamut from vociferous opposition to government actions and initiatives to apologetic defense and enthusiastic promotion of the same, differences arising even within a single issue. The Critic's relationship with the Kuomintang government has yet to be fully explored, but it is clear that it was no mere government mouthpiece. It is clear, too, that its members did not want or expect readers to treat its editorials as the end-point of their reading; as one editorial put it, 'only the dogmatic usually do not get further than magazine articles'—an observation that still rings true today. But while it held those readers' attention, The Critic at large tried to hold itself to a higher standard of journalism and criticism. That resolve would be sorely tested during the Sino-Japanese War, which saw constrictions placed on its editorial focus and a tempering of its outspokenness on sensitive issues.  Fig.3 The beginning of the end: the 8 October 1931 cover of The China Critic features a cartoon depicting Japanese aggression in the immediate aftermath of the 'September 18 Incident.' Cai Yuanpei's calligraphy adorned the front cover of each issue. For the student of the Chinese world today, The China Critic is significant in part because it has no successor in the contemporary People's Republic of China. China has state-run Anglophone general-interest publications, like China Daily, Global Times , the English edition of People's Daily (one of over a dozen foreign-language editions), and the business-focused Shanghai Daily (est. 1999),which have become markedly more sophisticated in their self-presentation in recent years but remain blatantly propagandistic. China has Anglophone academic journals, including joint ventures like Chinese Literature Today (whose website is hosted in the USA), lifestyle magazines, and expat periodicals.[7] And it has innumerable English-language blogs, run both by individuals and by various groups. Yet China lacks an equivalent to Taiwan's English-language newspapers, The Taipei Times (established in 1999), The China Post 英文中國郵報 (est. 1952), and, the now-digital Taiwan News (established in 1949 as China News and exclusively online since 2010). The Anglophone press of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, though markedly freer than that of the mainland, has been increasingly less so since 1997, with the venerable South China Morning Post (established in 1903) dogged by allegations of self-censorship and compromised editorial independence.[8] In contemporary China's media landscape, one that is so vastly different from that of The China Critic, print has a diminished, yet still important role in journalism and criticism. Print—the finality of ink on paper 白紙黑字—in some ways still represents the ultimate test of free speech, and no bricks-and-mortar, Chinese-edited Anglophone periodical currently operating in the People's Republic can credibly claim the same degree of editorial independence from the state that The China Critic enjoyed for most of its run. The Critic's independence was far from absolute; many of its leading editor-contributors had high-ranking government positions and duly championed official policies and pronouncements. Its combination of Chinese editorship, an English language medium, a commitment to in-depth analysis, and critical autonomy from the state nevertheless is conspicuously absent from mainland China's increasingly complex media terrain. This absence is due not to lack of talent or inclination in civil society, but to an adverse political climate. And this is why, even today, The China Critic looms large.

Editorials

Notes:[1] Ch'ien Chung-shu, 'Foreword', The Prose-poetry of Su Tung-P'o, translated by Cyril Drummond Le Gros Clark, Shanghai, 1935, pp.747-748; in Qian Zhongshu, A Collection of Qian Zhongshu's English Essays, Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2005, p.44. [2] [Anonymous], 'Editorial: Chinese Publications', The China Critic XII.10 (5 March 1936): 225. [3] Lin Yutang, 'The Little Critic: On Charm in Women', The China Critic XII.10 (5 March 1936): 231. [4] Yan-Ying Lu 盧延英, 'Confucianism: Its Past And Future', The China Critic VIII.2 (10 January 1935): 36-40. [5] See Shuang Shen, Cosmopolitan Publics: Anglophone Print Culture in Semi-Colonial Shanghai, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009, chapter 1. [6] Qian's indebtedness to Song dynasty poets and intellectuals, whom Qian remarked were 'nothing if not critical', is explained at length in a forthcoming book chapter by Wang Yugen. Among other observations in his English writings, Qian claims that it is not until the Song that literary criticism 'begins to be practiced in earnest', while noting that 'there do not appear professional critics with the rise of criticism'. See Qian Zhongshu, 'Foreword', The Prose-poetry of Su Tung-p'o (1935), in Qian, A Collection of Qian Zhongshu's English Essays, pp.43, 44. [7] Beijing Scene 新北京, one of the most influential China-based expatriate newspapers of the post-Reform era, began as an English weekly and added a Chinese edition and a bilingual web edition before it was shut down by the authorities. It was revived as a San Francisco-based website China Now, which appears to be currently inactive. 'Paper Tigers', an essay by Geremie R. Barmé about China's state-run press, was reprinted in Beijing Scene, vol.5, issue 25. [8] For one case from June 2012, see reports in: China Digital Times, Asia Sentinel, and The Guardian. South China Morning Post defended itself from the allegations with the following press statement: http://scmpgroup.com/pressroom/press_20120620.html. Hong Kong SAR's free English tabloid, The Standard, does not offer long-form analysis. |