|

||||||||||

|

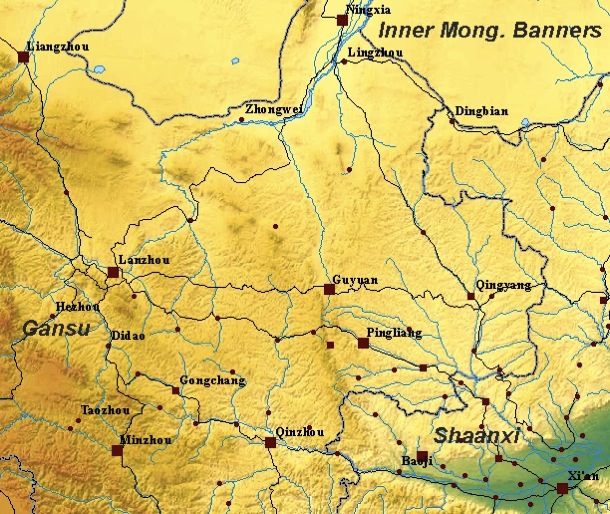

FEATURESRevolution, Counter-revolution, Devolution: Xinhai in Lingzhou, Gansu province 甘肅靈州Anthony Garnaut University of MelbourneThe Xinhai Revolution brought sudden changes to the status of different ethnic and religious communities in northwest China. After a successful uprising in the Shaanxi capital Xi'an, revolutionaries took control of a dozen towns and garrisons across Gansu, chased out the resident Manchu officials and established loosely linked revolutionary governments. Han and Muslim military officers, Muslim religious leaders and many members of the Han scholarly and merchant elite indigenous to Gansu rallied in opposition to the revolutionaries. An army was mobilised under the authority of Canggeng 長庚, the Manchu military governor of Shaanxi-Gansu, consisting of the dependable battalions of the regular provincial army bolstered by a large militia force. When Yuan Shikai was granted plenipotentiary powers over the Qing government, resolving ambiguities in the military chain of command, the fortified provincial army systematically suppressed the revolutionary governments in Gansu. It was fast approaching Xi'an when the last Qing emperor Xuantong (Aisin Gioro Puyi) abdicated the throne, and the formation of a new Republic was announced with Yuan Shikai as president.  Fig.1 Map of eastern Gansu

One of the important sites of fighting was Lingzhou 靈州, a small city in Ningxia prefecture on the southern back of the Yellow River. It was the first city in Gansu to fall to the revolutionaries (see map, Fig.1). The events that transpired there are described in three sources, reflecting the different perspectives of the main parties to the fighting: the revolutionaries, the Qing military governor who authorised the counter-revolutionary response, and the Muslim religious leader whose militia was directly responsible for the downfall of the Lingzhou revolutionary government. These sources shed light on the identities and motivations of the various groups that coalesced, clashed and dispersed during the four months between the Wuchang Uprising 武昌起義 and the proclamation of the Republic, a period when the regular bureaucratic chains of command that tied the provinces to Beijing were in disarray.[Fig.1] A brief history of the Lingzhou uprising was written by Li Yucun 李雨村, a teacher at a local secondary school teacher who interviewed several of the participants in the uprising in the 1950s.[1] His account highlights the prominent role played by the Brothers and Elders Society (Gelaohui 哥老會), and the absence of any direct connection between the participants and Sun Yatsen's Revolutionary Alliance until after the Wuchang Uprising. The membership of the local Society branch was predominantly Hunanese, a legacy of the Hunan army led by general Zuo Zongtang 左宗棠 that suppressed the great Muslim rebellion of the Tongzhi 同治 reign period (1862-1874). The organiser of the uprising was the local Society 'dragon head' (longtou 龍頭) named Gao Dengyun 高登云. After overcoming the small local garrison, he proclaimed the establishment of a revolutionary government under the name 'Han Restoration Army of Lingzhou' (Lingzhou Fu Han Jun 靈州復漢軍), with himself as general commander. Gao took pains to show that the 'Han' in the title of the revolutionary government was not exclusive of local Muslims, appointing as his deputy a local Muslim butcher named Ma Liandi 馬連第. Responding to the purportedly misguided views of many of his Society brethren, Gao Dengyun hung a banner affirming that the revolutionary government was following the anti-imperial, pro-republican program of General Sun Yat-sen, not a pro-Society program of self-enrichment. The reign of the Han Restoration Army of Lingzhou lasted for just under a month, upon which it was overrun by a Muslim militia force. Gao Dengyun fled while the city was laid siege to by the Muslim militia, and went on to a distinguished career as an organiser for the Nationalist Party. His Muslim deputy tried to negotiate the surrender of the city to the attacking militia. He was executed for his pains, along with several hundred associates of the revolutionary government, but only after leading the militia force into the city. The militiamen who spearheaded the counter-revolution were overwhelmingly Muslims hastily recruited from Hezhou 和州 and Ningxia prefectures. These had been the two main centres of Muslim power during the Tongzhi rebellion. The militias were led by a cohort of Muslim leaders who had served the Qing with distinction during its last decades, most of whom had close family ties to the Muslim leaders of the Tongzhi rebellion. The militia force that took Lingzhou was raised by a resident of nearby Guyuan 固原 prefecture named Ma Yuanzhang 馬元璋.[2] In the report on the Lingzhou uprising that he cabled to Yuan Shikai, Canggeng gave high praise for 'the Muslim gentryman' Ma Yuanzhang. He wrote: 'I have found that Ma Yuanzhang deployed more than a thousand militia in the field, and equipped them with fodder, grain, horses and camels entirely out of his personal resources. This clearly shows the depth of his loyalty.' He recommended that the contribution of Ma Yuanzhang, his militia officers and his fallen militiamen be duly honoured, advice that Yuan followed. Ma Yuanzhang continued to provide loyal service to Yuan Shikai into the early years of the Republic, brokering relations between the central authorities and various local revolutionary movements and militia groups throughout the Northwest. Ma Yuanzhang was also the shaykh or religious leader of the Jahriyya order, one of the largest Muslim religious communities of the Northwest. This role was not without worldly responsibilities—his predecessor as Jahriyya shaykh, Ma Hualong 馬化龍, had been the most powerful of the Muslim militia leaders during the Tongzhi rebellion. In the hagiography written by Zhan Ye 毡爺, a Jahriyya scholar and close supporter of Ma Yuanzhang, the campaign of the Muslim militia at Lingzhou is likened to the triumph of the early Muslim community over the Quraysh in the Battle of Badr, a victory that brought strength to the community of believers and laid the ground for greater victories to come. Zhan Ye writes: It is related that our perspicacious Mawlana Siddiq Allah [i.e. Ma Yuanzhang], God bless his soul, in the Eleventh Month of the Third Year of Xuantong [1911], amassed all under his command to go to Lingzhou. The campaign of Ma Yuanzhang's militia was authorised by military general Canggeng and endorsed by Yuan Shikai, the highest authority of the Qing government. The only hint provided by Zhan Ye of the existence of such a secular authority is the Qing imperial calendar that he uses to record the key dates of the battle. For Zhan Ye, the higher authority that gave legitimacy to Ma Yuanzhang's actions was God, Most Majestic. The victory at Lingzhou was yet one more incontrovertible sign of the coming of the age of Ma Yuanzhang, shaykh of the Jahriyya order, Seal of the Saints, Guide of the Last Days.  Fig. 2 Conference of Muslim leaders, Lanzhou, 1912. The Muslim military and militia leaders of Gansu including Ma Yuanzhang met in Lanzhou in April 1912 to discuss the new provincial political order following the announcement of the Republic of China. Ma Anliang (front row centre) was the most powerful of the Muslim leaders at the time of the conference. [Source: Rodney Gilbert, 'The Mohammedans of Western China', p.585.] The Xinhai Revolution is often presented as a failed revolution, a revolution betrayed by Yuan Shikai and the lesser military figures that came after him. For the protagonists of the three accounts discussed here, the battle of Lingzhou did not end failure. Li Yucun presented the Lingzhou uprising as a small opening salvo in a forty-year revolutionary struggle in the Ningxia district. Though many of the participants in the Lingzhou uprising were killed by Ma Yuanzhang's militia, its leader Gao Dengyun managed to flee the city and went on to a distinguished career as an organiser for the Nationalist Party. Canggeng presented the suppression of the uprising as one of many such campaigns prosecuted by the military forces of the Qing, a routine event to which a standardised system of rewards and merits could be applied. Following the abdication of the last Qing emperor, Yuan Shikai asked that he serve as the inaugural governor of republican Gansu, but Canggeng opted instead for an honourable retirement.[Fig.2] This left Gansu under the de facto control of the predominantly Muslim military commanders who had suppressed the revolution. This was a similar position to that which the Muslim generals and militia leaders of the Northwest had found themselves fifty years earlier, after resisting the incursion into the region of one of the Taiping revolutionary armies. Back then, the Muslim generals were unable to have their de facto power legitimated by the central government, and the long Northwest campaign of Zuo Zongtang was the result. After Xinhai, the Muslim generals were relatively successful in incorporating themselves within the new republican political order. For Ma Yuanzhang, the Xinhai revolution provided the occasion for him to cement his claim over the leadership of the Jahriyya order, and also to achieve what had narrowly eluded his predecessor as Jahriyya shaykh forty years before. This was to establish a realm in eastern Gansu that was constituted both as an autonomous Muslim territory and a loyal region of a greater Chinese polity.[4] Notes:[1] Li Yucun 李雨村, 'The popular uprising in Lingzhou, Ningxia, during the Xinhai Revolution' (Xinhai geming Ningxia Lingzhou minjun qiyi 辛亥革命宁夏灵州民军起义), Ningxia wenshi ziliao, 7 (1981). [2] 'Memorial of Canggeng to Yuan Shikai, Eighth Day of the Twelfth Month of the Third Year of Xuantong', in Chai Degeng 柴德赓 ed., The 1911 Revolution (Xinhai geming 辛亥革命), Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1957, vol.6. [3] Zhan Ye 毡爷, n.d. (c2000), Manaqib (Mannageibu 曼纳给布), trans. Huang Siming 黄思明 and Ma Chengxiang 马成祥, Yinchuan: Yinchuan Dongsi, 2000, p.161. [4] The nature of this territorial authority, and its relationship with the republican government in Beijing, are explored in the author's doctoral dissertation, 'The Shaykh of the Great Northwest: The Religious and Political Life of Ma Yuanzhang (1853-1920)', The Australian National University, 2011. References:Rodney Gilbert, 'The Mohammedans of Western China: The political and religious aspirations of a virile but little known people', The Far Eastern Review, September 1919: 585-589. Articles included in this feature:

|