|

||||||||||

|

FEATURESYang Jiang's 楊絳 Conspicuous Inconspicuousness A Centenary Writer in China's 'Prosperous Age'Christopher G. Rea University of British Columbia

The writer and literary figure Yang Jiang celebrates her centenary on 17 July 2011. Christopher Rea, a scholar of Republican-era literature, translator and specialist in Chinese humour, reflects on Yang's century. Christopher Rea is an assistant professor of modern Chinese literature at the University of British Columbia. He is the editor of a special issue of the Chinese University of Hong Kong journal of translation Renditions on the works of Yang Jiang, which will be published this autumn (southern spring); of the book Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts: Stories and Essays by Qian Zhongshu, New York: Columbia University Press, 2011; and, of a planned volume provisionally entitled China's Literary Cosmopolitans: Qian Zhongshu, Yang Jiang, and the World of Modern Letters. In 2012, he will be a post-doctoral fellow at the Australian Centre on China in the World at the Australian National University.—The Editor

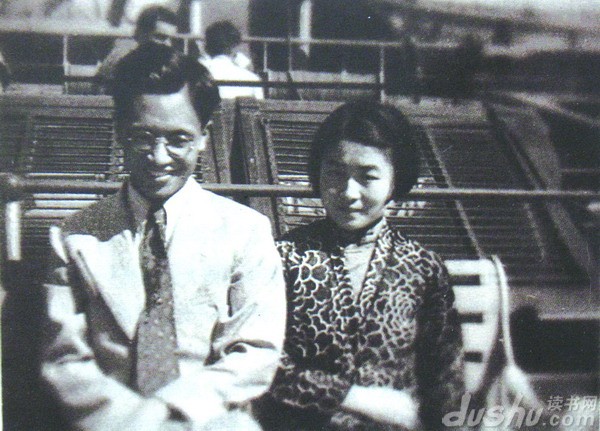

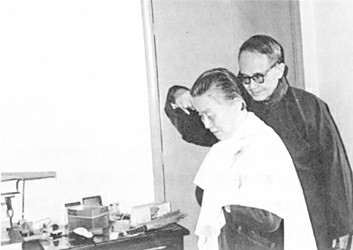

'I was the same person I had always been.' 我還是依然故我  Fig.1 Yang Jiang In Chan Koon-chung's 陳冠中 novel, The Prosperous Age: China 2013 (Shengshi: Zhongguo 2013 盛世:中國2013年, 2009), the protagonist, Lao Chen, visits Sanlian Bookstore 三聯書店, a cultural watering hole and the haunt of many Beijing intellectuals.[1] He is one of only a few people in China not suffering from collective amnesia, and he has just begun a quest to get to the bottom of the peculiar euphoria of his countrymen. His acquaintance, Fang Caodi, remarks as he drops Lao Chen off: 'Lao Chen, I'll bet you they don't even sell books by Yang Jiang 楊絳.' Lao Chen dismisses the thought—Yang's works were best-sellers; Sanlian must carry them. As soon as Lao Chen entered the bookstore, he asked the counter clerk to look up Yang Jiang's works on the computer. Looking at the computer, the clerk said 'There aren't any.' Contemporary young people are not very familiar with books, Lao Chen thought and said 'Out of stock, right?' 'There is no reference for such books, we've never had them.' 'What about some time earlier?' 'There is no record of our ever having them.' 'We Three [我們仨] is a Sanlian publication!' 'I don't know about that, but there is no record on the computer.' Lao Chen checks with the bookstore manager, who asks 'Which Yang Jiang?' and, when reminded, confirms that 'probably nobody reads her anymore.' Back home, Lao Chen checks online bookstores for her work, but can't find anything.  Fig.2 Cover of We Three (我們仨) Why would a nonagenarian writer appear in a dystopian political novel, especially one whose critique of the Chinese Communist Party was so overt that it led to its banning in Mainland China? What would it mean for China to have forgotten Yang Jiang? Yang's conspicuous mention in Chan's novel is an index to how culture itself is being re-defined in within a broader contemporary cultural discourse in the People's Republic of China. Yang Jiang has, of course, long been a respected name among establishment intellectuals, noted for her plain yet elegant prose style and her diverse literary accomplishments. Since at least the 1980s, when many Republican-era writers were rediscovered and reprinted, her fame has also been attributable in part to her spousal relationship with the famous writer-scholar Qian Zhongshu 錢鍾書 (1910-1998), who is a key subject in many of her essays and memoirs. But in the past five years she has also become an object of veneration among young Chinese bloggers, who have found things about her to appreciate beyond her works alone. By what measures is one of modern China's longest writing lives being re-assessed in the twenty-first century? More broadly, what type of cultural politics has Yang Jiang come to symbolize in contemporary China's purported 'prosperous age'? This essay does not offer a comprehensive appraisal of Yang's literary oeuvre but instead touches on several questions of self-representation and reception. It argues that while Yang's literary works continue to be read and appreciated, her status as a cultural icon has been propelled in part by a broader discourse about literary and moral values centered around her and her late husband (in which she has been an active participant). It further argues that Yang has become an influential exemplar and revitalizer of a traditional Chinese ideal of literary authenticity: namely, that 'the writing mirrors the writer' (wen ru qi ren 文如其人) and vice versa. Yang Jiang is a top-tier writer in China in terms of name recognition, and the run-up to today—her one hundredth birthday—has seen a wave of essays, editorials, personal visits by top PRC political officials,[2] and a new unauthorized biography.[3] Retrospectives have considered a writing career that is notable for being not only one of modern China's longest, but also one of its most varied. Having published her first short stories in graduate school, after further studies in Europe she distinguished herself as a playwright in occupied Shanghai with two successful comedies.[4] Following a time as a professor at her graduate alma mater, Tsinghua University, from 1953 until her retirement in the 1980s, apart from a period of rustication in the Cultural Revolution, she worked alongside Qian as a researcher in an elite academic institute in Beijing. During that tenure, she published several short works of literary criticism, and translated three classic picaresque novels from multiple Western languages: Lazarillo de Tormes 小癩子 (English re-trans., 1950; Spanish, 1977), Gil Blas 吉爾•布拉斯 (French, 1956) and Don Quixote 堂吉訶德 (Spanish, 1978).  Fig.3 Yang Jiang with husband Qian Zhongshu in 1935 Had Yang's writing career ended with the Mao period, she would be remembered as an accomplished translator and a talented comic playwright. But her literary output during the post-1978 era of 'Reform and the Open Door', which also saw the emergence of a new generation of Chinese writers and artists, ranks as one of the most remarkable authorial re-births in modern Chinese literary history in terms of both quantity and quality. (See a brief video featuring Wendy Larson on Yang's literary career.[5]) Already in her sixties by the time Mao died in 1976, Yang resumed writing short stories for the first time since the 1940s, and also emerged as a major essayist, publishing several collections on sundry topics. In the early 1980s, she published a landmark work, Six Chapters from a Cadre School 干校六記 (1981, discussed in another video[6]), an account of the quotidian experience of political 're-education' in the countryside whose tone of studied understatement distinguished it from the hyperbolic wound-bearing of many Cultural Revolution memoirs. Following her retirement from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, she published her only novel, Baptism 洗澡 (1988), a tragicomedy about academics undergoing the first major thought reform campaign of the Mao era in the early 1950s. Rounding out her 'late period' (so far) has been a re-translation of Plato's Phaedo 斐多 (English re-trans., 2000), the mixed-genre memoir, We Three (2003), and an essay-collection-cum-philosophical-treatise, Arriving at the Margins of Life: Answering My Own Questions (Zoudao rensheng bianshang: zi wen zi da 走到人生邊上:自問自答, 2007). Given surprises of the past decade, it would be premature to declare the book closed on Yang Jiang. Yang's famously unadorned prose style has widely been taken as a reflection of her personal diffidence. Her approved biographer, Wu Xuezhao 吳學昭, writes that Yang 'refuses to stand out' (jue bu chutou 絕不出頭) and 'is utterly content always being a zero' (zijue ziyuan shizhong zuo ling 自覺自願始終做零).[7] Her books sell by the millions, but since 2001 she has given away the royalties from her and Qian's works to endow a 'Philobiblon' (hao du shu 好讀書) scholarship for Tsinghua students.[8] One scholarship recipient is said to have remarked, upon seeing her Spartan dwelling, that Yang embodied Wordsworth's ideal of 'plain living and high thinking.'[9] Yet, as I argue in a forthcoming essay, Yang's (auto)biographical and curatorial efforts create some friction with her reputation as a paragon of self-effacing modesty. Despite publicly discouraging the well-wishers constantly imposing themselves on her self-chosen hermitage, as a writer she has repeatedly put herself in the public eye through the virtual medium of print. She has positioned herself as an arbiter of public discourse about Qian Zhongshu, one of China's most esteemed scholar-writers. She has dictated a 'biography' to a close friend. Yang, who once wished for a 'cloak of invisibility',[10] has in fact devoted the latter part of her career to being conspicuously inconspicuous.  Fig.4 Yang Jiang in the 1940s Autobiography has been crucial to this process. Yang's reputation as a paragon of constancy, for instance, is thanks in part to her explaining life decisions in terms of patriotism. While an undergraduate at Soochow University, she was offered a full tuition scholarship to attend Wellesley College, but she turned it down to stay in China and study foreign languages at Tsinghua, worried that her living expenses would be a burden on her father. When the Communists were on the cusp of winning the Civil War, she and Qian turned down positions at universities abroad. During the 1980s, both were again courted with multi-year fellowships from foreign institutions but limited themselves to brief overseas tours (Qian of Italy and the United States; Yang of Spain and England after she finished translating Don Quixote). Self-avowed homebodies, they preferred 'armchair travel' (wo you 臥遊) to the types of prestigious overseas fellowships that many of their peers would have jumped for. Yang and Qian believed in their motherland before the coming of the 'prosperous age' Lao Chen inhabits, in which common wisdom has it that 'China is the place to be'. Another obvious answer to why Yang is so important in twenty-first-century China is that she is an epochal figure in a nation obsessed with its own history. Symbolically, her birth during the 1911 Revolution, a few months before the official founding of the Republic of China, begs comparison with such fictional figures as Lin Kang-ming in Hou Hsiao-hsien's 侯孝賢 A City of Sadness (Beiqing chengshi 悲情城市, 1989) or Saleem Sanai in Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children (1981), the former born during Emperor Hirohito's announcement of Japan's WWII surrender (15 August 1945) and the latter upon the stroke of midnight marking the independence and partition of India (15 August 1947). Her life has spanned that of modern China. As a centenarian, Yang represents a near-vanished generation of intellectuals who came of age during the Republic, had first-hand experience of the Japanese occupation, saw their works largely ignored or forgotten during the Mao era, and experienced China's subsequent rapid social and economic transformations along with their own literary 'resurrections' as senior citizens. Yet Yang has become a symbol of stoicism and resilience for having endured not only the same Maoist political campaigns as her peers, but also personal tragedy in the loss of her two closest family members. Revered for her sheer longevity and senior standing as one of the oldest of the 'old-style' (laopai 老派) intellectuals, she has projected a humanistic ethos that, though dismissed by some Chinese readers as outdated, many others have found estimable and comforting. Indeed, one reason why Yang is not merely a symbol of a bygone age is that her writings, especially those about her family, have resonated with a new generation of Chinese readers. Particularly well known is her 2003 book We Three—part memoir, part dream-fiction, and part family scrapbook—which recounts her emotional experience of losing her daughter and husband to illness in 1997 and 1998 and reconstructs their life together. Often as poignant and heart-wrenching as Joyce Carol Oates's A Widow's Story (2011), We Three has become the nucleus of a modern love fable. The story of Yang's marriage with Qian Zhongshu has been told and re-told as a lasting intellectual and emotional bond of mutual devotion, based, for the most part, on the testimony of Yang and Wu Xuezhao. From Wu's biography we learn that Qian once praised her as 'an almost impossible combination of 3 incompatible things: wife, mistress and friend.'[11] Yang, meanwhile, has written at length about her devotion to her husband, not least her service as intellectual partner and first reader of his work, domestic laborer who took on menial tasks to give him the freedom to write,[12] and nurse during the years of his final illness. On the web, their relationship is said to have begun as 'love at first sight between a brilliant man and a brilliant woman' (yi jian zhongqingde caizi cainü 一見鍾情的才子才女),[13] and been nurtured by a 'love to topple a city' (qing cheng zhi lian 傾城之戀)[14] into a 'legendary marriage' (hunyin chuanqi 婚姻傳奇).[15]  Fig.5 Yang Jiang and Qian Zhongshu But while We Three is a work of grief and commemoration, it is also part of an individual struggle over public memory. While known for being 'low key' (di diao 低調) in both prose style and lifestyle, Yang's tenacious efforts as a widow and a bereft mother to control the discourse over public perceptions of her family have been anything but. As biographies of her husband (since the 1980s) and herself (since the 1990s) began proliferating, she has taken it upon herself to clear up contested biographical matters; dispute allegations of Qian's intellectual arrogance and the couple's aloofness; assist with the editing and compiling of his published works and reading notes; and release a treasure trove of archival materials from her personal collection. While Yang's literary persona has been intimately tied to Qian Zhongshu since Six Chapters, her recent writings have focused even more intently on him (and, to a lesser extent, her daughter Qian Yuan) as a literary subject. Qian's death may have afforded Yang an unprecedented degree of autonomy, but she has bound herself to him even more tightly by emphasizing her status as a loyal widow.[16] Since the 1980s, Yang has done much to enhance Qian's reputation, and her reference to herself as a 'zero' oddly resonates with an ironic quip from Qian's 1946 story, 'Cat': Mrs. Li knew that such a husband was as indispensible as the zero in Arabic numerals. Though zero itself has no value, without it one could not make ten, one hundred, one thousand, or even ten thousand. Any figure multiplies tenfold when a zero is added, so the zero, accordingly, gains significance by following it.[17] This passage, of course, if anything belies Yang's self-deprecating claim, as she has done far more than just stand behind her man. As her readers know well, Yang's literary fame actually preceded Qian's—her wartime plays not only won acclaim in Shanghai but are said to have inspired Qian's own literary efforts. (A systematic study of their mutual literary influence has yet to be written.) With Yang now claiming to speak for them both, it is easy to forget how different the two writers are in style and voice. More broadly, as a memoirist, and one of our chief first-hand sources of information about one of modern China's most prestigious pairs of writer-scholars, Yang Jiang is both a repository and a generator of public cultural memory. She is a symbol of the bygone 'prosperous age' of great minds and literary talents who emerged from elite institutions like Tsinghua in the 1930s and made their first marks on modern Chinese cultural history under the trying circumstances of foreign occupation. Further, as Yang has long been in the actuarial 'death zone', that memory has for a while now been on the brink of expiring for good—just as a 'prosperous age' is always potentially on the verge of ending. However long she may end up living, Yang's centenary represents a symbolic moment of cultural eclipse, albeit one—as Qian appreciated[18]—that can endlessly be regenerated through commemoration. A sense of disappearance is evident in Arriving at the Margins of Life (2007), a self-reckoning that may well be Yang's most personal book. Written in her late nineties after a brief hospitalization, the book returns to the theme of 'marginality' which appears in the title of Qian Zhongshu's 1941 essay collection, Written in the Margins of Life (Xie zai rensheng bianshang 寫在人生邊上), which Yang compiled. The first half of the book is structured as a self-dialogue about life, death, and the afterlife; the second part contains an assortment of family anecdotes and reading notes—the fragments of a life. What emerges from its pages is not merely the predictable inward turn toward self-consolation of a learned person facing death; in Yang's declaration of faith and her insistence that the afterlife be 'fair' is an affirmation of personal metaphysics in a nation that has long promoted collectivism while discouraging religion and 'superstition'. The arc of We Three ends with Yang alone, an existential figure trying to live on after loss. Margins elevates Yang to philosophical seeker and sage. Taken together, Yang's late works project the persona of an individual who is not just alone, but singular. Given to 'closing her door to visitors' (bi men xie ke 閉門謝客), Yang signifies that nowadays it is still possible to block out the clamor of a chaotic outside world and focus on self-cultivation. Judged by her late-life output, which in the Chinese press and blogosphere has recently attracted more discussion than her earlier 'classics,' Yang's twenty-first century reception represents a very modernist brand of anticipatory nostalgia—a society's belated consciousness that it is soon to lose touch with a living link to the memory and humanistic conscience of an earlier era. Chan Koon-chung's fantasy that We Three would disappear a mere decade after its publication, moreover, suggests a concern that the pace of loss is accelerating. China's gaze at Yang Jiang, in other words, looks both backward and forward. While a few critics have pointed out gaps and misrepresentations in Yang's recollections or criticized her translations,[19] scholars can only speculate about what further critiques will emerge after Yang is no longer around to validate or reprove them. What is certain is that she will be remembered as the self-seeker whose linguistic power shines through in such moments as the defiant conclusion to her Cultural Revolution memoir: 'It was clear to me that despite more than ten years of ideological reform and two years in a cadre school I still hadn't managed to get rid of my own selfishness, nor did I achieve the personal transformation that others had sought after so diligently. I was the same person I had always been.'[20] Yang's writings have given us greater access to the physical, intellectual, and emotional lives of modern Chinese intellectuals than anyone could have anticipated. Nevertheless, there are always more chapters yet to be written. Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes:[1] For the complete passage, see Chen Guanzhong 陳冠中 [Chan Koonchung]. Shengshi: Zhongguo 2013 nian 盛世:中國2013年, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp.129-133. Thanks to Judy Amory for alerting me to the reference last fall, and to Michael Duke for allowing me to use this modified excerpt from his translation of the novel, The Fat Years (Doubleday, 2011). Duke translates Women sa as The Three of Us; here modified to We Three; Duke also modifies Fang Caodi's comment for the benefit of English readers unfamiliar with Yang's works to read: 'Lao Chen, I'll bet you they don't even sell Yang Jiang's famous plays and memoirs, especially not about the Cultural Revolution,' alluding to Yang's memoir, Six Chapters from a Cadre School. Unless otherwise noted, all websites cited in this essay were accessed between 25 June and 2 July 2011. For a translation of this book, with an introduction by Simon Leys, see Yang Jiang, Lost in the Crowd, trans. Geremie Barmé, Melbourne: McPhee Gribble, 1989. [2] See: 'Top Political Advisor [Jia Qinglin 賈慶林, Chairman of the National Committee of the CPPCC] Visits Authoress Yang Jiang', online at: http://www.womenofchina.cn/html/report/125315-1.htm [3] The release of the biography, written by Luo Yinsheng 羅銀勝, was announced in June 2011. See: http://dszb.whdszb.com/whdszb/html/2011-06/24/content_96031.htm [4] After the war, Yang also published a tragedy, which was reportedly not produced, and third comedy, which was produced but is not extant. [5] See: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wrqIIeX6XjM&feature=related [6] See: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g_dazSBSCXY&feature=iv&annotation_id=annotation_646293 [7] Wu Xuezhao 吳學昭, 'Listening to Yang Jiang Talk About the Past' (Ting Yang Jiang tan wangshi 聼楊絳談往事), Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, 2008, p.336; see also pp.278 & 287. [8] We Three sold over five million copies in China during its first five years in print. The English name of the scholarship is the same as that of the English-language publication that Qian once edited for the National Central Library in Nanjing (see China Heritage Quarterly: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/tien-hsia.php?searchterm=025_decadent.inc&issue=025 ). See also Wu Xuezhao, 'Listening to Yang Jiang Talk About the Past', pp.398 & 404 (Wu misspells the English name of the scholarship). For the announcement of the scholarship in the official media, see: http://news.xinhuanet.com/book/2003-09/02/content_1058738.htm [9] Wu Xuezhao, 'Listening to Yang Jiang Talk About the Past', p.402. [10] For an English translation of 'Cloak of Invisibility' (Yinshen Yi 隐身衣), see: David Pollard. The Chinese Essay, New York: Columbia University Press, 1984, pp.264-269. [Ed. Note: the essay, translated by a different hand, also appears as the afterword to Yang's Lost in the Crowd.] [11] Qian's dedication plays on the tripartite title of his short story collection Human, Beast, Ghost (Ren Shou Gui 人獸鬼, 1946). An image of the inscribed book cover is reprinted in Wu Xuezhao, 'Listening to Yang Jiang Talk About the Past', p.219. [12] Jesse Field, author of a forthcoming dissertation about Yang Jiang, notes Yang's characterization of herself as a 'scullery maid' (zaoxia bi 灶下婢) and as handmaiden to Qian's famous novel Fortress Besieged (Wei Cheng 圍城, 1946-1947). See: Jesse Field, '"All Alone, I Think Back on We Three": Death, Memorial, and Yang Jiang's New Intimate Public', unpublished workshop paper, pp.13 & 29, n.19. Field's translation of the essay in which Yang first uses the term 'scullery maid', 'On Qian Zhongshu and Fortress Besieged' (Ji Qian Zhongshu yu Wei Cheng 記錢鍾書與《圍城》, 1982) will appear in Renditions this autumn (southern spring). [13] See: http://news.xinhuanet.com/book/2011-01/31/c_121044920.htm [14] See: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_5e6ffaf70100lawd.html [15] See: http://history.stnn.cc/arts/201006/t20100607_1338572.html [16] Even Yang's authorized biography, the publication of which was timed to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Qian's death, ends with a line affirming the pair's inseparability (Qian Yang shi buke fende 錢楊是不可分的). See Wu Xuezhao, 'Listening to Yang Jiang Talk About the Past', p. 413. The collective impression of Yang's (auto)biographical writings is that their daughter Qian Yuan, despite her mother's posthumous efforts to memorialize her, was something of a third wheel in the familial relationship. [17] Qian Zhongshu, 'Cat', Yiran Mao, trans., in Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts: Stories and Essays, Christopher G. Rea, ed., New York: Columbia University Press, 2011, pp.112-13. [18] See Qian's epigram about men of letters and commemoration: http://www.thechinabeat.org/?tag=qian-zhongshu [19] See, for example, this widely-reposted article from Southern Culture (Nanfang Wenhua 南方文化) about the scholar Fan Xulun's 范旭侖 complaints that Wu's biography is full of omissions and mis-recollections by Yang, and that it repeats much of We Three: http://www.tianya.cn/publicforum/content/books/1/113187.shtml. On alleged omissions and mistakes in Yang's translation of Don Quixote, see: http://big5.cri.cn/gate/big5/gb.cri.cn/3601/2005/09/07/882@690250.htm. [20] Yang Jiang, Lost in the Crowd: A Cultural Revolution Memoir, trans. G Barmé, p.126. |