|

||||||||||

|

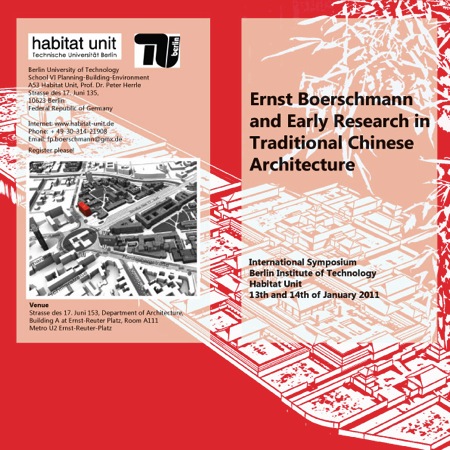

FEATURESResearching Ernst BoerschmannEduard Kögel Director of the Ernst Boerschmann Research Project Berlin University of Technology (Technische Universität Berlin)The German architect and historian Ernst Boerschmann (1873–1949) spent his professional life engaged in research on traditional Chinese architecture. Between 1924 and 1944 as a professor at Technische Hochschule Charlottenburg, today's Berlin Institute of Technology, he taught Chinese architecture. Presently at the Habitat Unit of that institution I am leading a research project to illuminate the full scope of Boerschmann's work and his achievements as one of the first Western scholars to focus on architectural history in China. When Ernst Boerschmann first arrived China in 1902 as a member of the German army he was already planning to undertake work on architecture. During his two-year sojourn he took detailed measurements at Temple of Azure Clouds (Biyun Si 碧雲寺) in the Western Hills of Beijing. With the publication of the results of that endeavour and with the help of influential political friends he convinced the German Reichstag to fund a three-year research trip, from 1906-1909. Initially, he attempted to embark up systematic documentation of the buildings that interested him, but soon realised that without a focussed strategy and methodology this would be impossible. In his funding to the Reichstag he had identified two foci of his work: religious culture and architecture in the landscape. Having arrived in China he realized that he also needed a means to cover the vast territory of the Qing Empire.  Fig.1 Flyer for the international symposium on the theme 'Ernst Boerschmann and Early Research in Traditional Chinese Architecture' to be held in Berlin on 13-14 January 2010. Click here for details. His interest in religious architecture allowed him to organise travel around the the religious/spiritual geography of the country, in particular the nine sacred mountains, five of which were of significance to Taoism and four of which were particular to Buddhism. He concluded that these geographical sites must also be the locus of major religious structures. From that he developed an itinerary to visit these mountains. Like many of his contemporaries he also thought of Confucianism as a religion and he included the temples of Confucius in his study. During the following three years he visited eighteen provinces. The longest expedition lasted for more than a year and took him overland from Beijing to Chengdu, Sichuan province, down the Yangtze River and further on to Guangzhou, in Guangdong province, from where he returned via ship along the coast to the imperial capital. During this particular trip he visited three of the sacred mountains of Taoism and three that were sacred to Buddhism. Back in Germany the Foreign Office continued to support his studies until 1914. He was able to publish two big books in the series The Architecture and Religious Culture of the Chinese. The first volume, which appeared in 1911, was devoted to the Buddhist temple island of Putuo Shan 普陀山. The second work, which was published in 1914, was on the architecture 'of the old Chinese cultural circle' (that is buildings from the pre-Buddhist era of China), which complemented the previous volume. Under the title Gedächtnistempel he produced three monographs on temples dedicated to ancient heroes, namely the Zhang Liang Temple 張良祠 near Hanzhong in Shaanxi province (see 'The Temple of the Marquis of Liu' in Features), the Two King Temple (Er Wang Miao 二王廟) at Dujiangyan 都江堰 in Sichuan and the Temple of Confucius 孔廟 in Qufu 曲阜, Shandong. All of these sites are carefully documented through plans, sketches and photographs. In each volume Boerschmann included various minor buildings, such as those related to Confucius or ancestor worship. In 1912, Boerschmann was able to to curate an exhibition on Chinese architecture at the Kunstgewerbe-Museum in Berlin, which was accompanied by a small catalogue. Between 1914 and 1921, WWI and the subsequent political unrest in Germany prevented him from undertaking further study. But, in the early 1920s, Boerschmann was able to attract support for his research from the German Foreign Office. In 1923, he published his most successful book, Picturesque China, which boasted a print-run of 20,000 in German alone. In addition to that two English versions have been released, one in London the other in New York. In the following year he embarked upon a teaching career (becoming a professor in 1927) at Technische Hochschule Charlottenburg and, in 1925, he published a two-volume work titled Chinesische Architektur. This was followed in 1927 by a book on architectural ceramics. In 1931, the first volume of his two-volume opus on Chinese pagodas appeared. He worked on revising volume two until it finally appeared in 1942. In 1931, the noted Chinese architectural expert Zhu Qiqian 朱啓鈐 invited Boerschmann to become a corresponding member of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture in Beijing (see the Editorial in this issue). By this stage his work was well known among scholars and also stimulated research among Chinese specialists. Apart from Boerschmann, the German art historian Gustav Ecke was also a member of the Society. In 1933, Boerschmann secured public support for a two-year research trip to China. On many of his trips around the country he was accompanied by Hsia Changshi, a young architect and art historian educated in Germany. Due to his work on identifying and studying what he termed 'tropical architecture' Hsia became a leading figure in Guangzhou in the 1950s. Boerschmann also was a close friend of the art historian Teng Gu and meet with many important politicians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China from 1928. He used his time in China to visit the three sacred mountains he had failed to reach during his first research trip and to contemplate in a systematic way the relationship between geography, religion and the placement of pagodas in the landscape. Back in Beijing he meet with Liang Sicheng 梁思成 (1901-72) and Liu Dunzhen 劉敦楨 (1897-1968) in the hope of developing a collaborative project. These two noted Chinese architectural specialists, however, pursued an interest in architectural history and evinced scant interest in the socio-religious context of culture so valued by Boerschmann. He always believed that Chinese architecture could only be understood by analysing the close connection with religious purpose whereas Liang Sicheng, a scholar educated at Pennsylvania State University, was intent on transplanting Beaux Arts historiography into the Chinese context. Such transculturation and the analysis of the traditional building manuals like Yingzhao Fashi 营造法式 would become the basis for the study in ancient architecture in China. After his second major research trip the political situation in Germany and the official relationship with China made Boerschmann's work difficult. He found it nigh on impossible to publish new works. He had returned to Germany in 1935, whereupon he pursued work on the second volume of his pagoda book. In 1942, although it was ready for publication it, along with all other scholastic works at the time, failed to appear due to the war. Between 1940 and 1944, Boerschmann also taught at Berlin University (now Humboldt-University). Following the war he continued to teach, occupying the chair of Sinology at Hamburg University until his death in 1949. After the depredations of war, material scarcity and reduced finances made it difficult to survive, let alone publish new work. There has been a persistent misunderstanding of Boerschmann's approach, in particular he has been criticised for an excessive concentration on the relatively new buildings of the Ming and Qing dynasties. He took this approach on the basis of a well-considered rationale. When he began his research in the early twentieth century not much was known about Chinese architecture and in some cases he also made errors due to a lack of accurate information. But his measurements and his detailed documentation of Ming and Qing architecture remain of considerable value today. As he was mindful of the limitations of his work, Boerschmann himself suggested that his oeuvre be regarded as an archive of materials that would require suitable classification by later generations. He started with the architecture of the Ming and Qing dynasties due to the simple fact that there were numerous ext ant structures available for study. He argued that eventually, once the underlying principles behind these structures was better understood, it would be possible to venture deeper into history and focus on older buildings. In his work on pagodas he used this approach as a guiding and organising principle. Ernst Boerschmann spent his professional life engaged in the study of traditional Chinese architecture. During that time he was without doubt the leading expert on the subject in the German-speaking world. But the limitations of German as a language for research and publication made it difficult for international scholars to study his work in depth or to pursue the classification project that he had initiated. With the support of German Research Foundation a team of scholars with the Habitat Unit at Berlin University of Technology are now working to bring to light the achievements, value and intellectual structure that lies at the basis of Boerschmann's work. Since many of the buildings that he photographed and drew during his expeditions to China have changed or been destroyed during the course of the twentieth century, we are sure that the visual and scholastic documentation of Ernst Boerschmann can help heritage reconstruction projects as well as contribute to the understanding of numerous significant structures. An international symposium on the theme 'Ernst Boerschmann and Early Research in Traditional Chinese Architecture' will be held in Berlin on 13-14 January 2010. For more details of this, and of the Habitat Unit of the Berlin University of Technology (TU Berlin), visit the symposium website. |