|

||||||||||

|

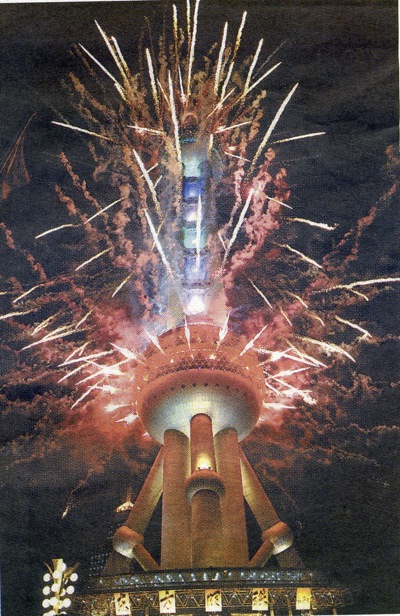

FEATURESSub-UrbiaJonathan HuttThe protracted debutante ball that is Shanghai Expo has brought to light one of the great ironies in the Shanghai mythology. Despite the highly polished veneer of an international metropolis, the city is still clearly driven by an almost adolescent need for attention and/or validation from its peers. Yet, as followers of the Oriental Pearl know all too well, all such efforts over the last century have ended with at best abject failure, and at worst unparalleled disaster. Little wonder then that in planning this ‘coming of age’ spectacle, this latest generation of Shanghai officialdom has been so keen to avoid the pitfalls of the past. Despite their endeavours, the signs were far from promising; from the chaotic start for its new $2.2 billion domestic airport terminal and the most underwhelming of opening ceremonies on May Day to the apparent lack of paying guests in the early days of the extravaganza. The waves of anxiety that followed were almost palpable.  Fig.1 Pearl of the Orient, fireworks crescendo during the Shanghai Expo Opening Ceremony. To the astonishment of the city’s admirers and detractors alike, however, Expo is proving to be exactly the kind of crowd-pleasing spectacle that the city’s spin-doctors had long predicted. Given the international community’s disinterest in and/or ignorance of a dying franchise, the Expo euphoria was always destined to be a domestic concern. Herein lies Shanghai’s greatest ‘success’—for it has achieved what many would have deemed impossible. By winning over the greater Chinese public it has managed to garner praise from those who were united by their visceral and almost universal hatred of the city and its native inhabitants within China itself. Sadly, what for some is a glittering prize is for others a source of shame. Here, they say, is a city that threw off the shackles of tradition and, in doing so, became Asia’s first great metropolis; it is a city which sought to align itself with the great cities across the globe and whose inhabitants were deemed ambassadors for a new Chinese civilization. How then could the world and their fellow sophisticates show such disregard for such a critical moment in Shanghai’s evolution? How could a city that scoffs at the parochial manners of their country cousins now be forced to serve as a glorified theme park for the seething provincial masses? For some it is, in the words of Agatha Runcible, just ‘too, too shame-making.’ That this shame is far from universal hints at a subtle and important change in Shanghai’s on-going identity crisis and its shifting position within the Chinese and Western worlds. As always these transformations are best illustrated by changes in the city’s awkward relationship with and increasingly one-dimensional understanding of its own past. While Shanghai’s plundering of its history for decorative motifs is already a long-standing, if largely unsuccessful, neo-tradition, the notion that there might be yet another ‘Republican revival’ should be decidedly passé. The much-hyped opening of Gosney & Kallman’s ‘Chinatown’ on Zhapu Road 乍浦路 in Hongkou 虹口 in 2009 was thus an audacious venture (see: www.chinatownshanghai.com). Billed as the PRC’s first burlesque club and ‘occupying an extraordinary piece of Shanghai’s architectural heritage—a 1931 Buddhist shrine in atmospheric Hongkou District’, it is said to offer its clientele ‘music, dancing girls, tease shows and lacy, racing, revealing costumes…two shows a night aim to titillate while historical drinks are poured at the bar’ (see: http://www.cityweekend.com.cn/shanghai/listings/nightlife/nightclub/has/chinatown/) Hongkou’s tattered reputation today together with the critical role the area played in the evolution of Republican Shanghai’s hedonistic mythology, should have aided ‘Chinatown’ in its attempts to evoke the tawdry glamour of a bygone age. Sadly, the world it evokes is all too familiar. This is neither an escape from nor a negation of the malevolent urban environment, but rather a hedonistic celebration of its charms. Is it but a manufactured playground for the legal firm’s Christmas function, the drunken British Hen Party, and the Minhang 閔行 A-list? No fast track to moral decline here, merely a subway station on the line to the suburbs. Without question it is the ‘sur-banization’ of the Shanghai mind that has created new physical and psychological landscapes in the city. Yet, as to what impact they will have on how the Shanghai perceives itself, is perceived and how these perceptions will shape the pursuit of a new Chinese urban utopia remains to be seen. Is this a betrayal of the ideals set forth by Shanghai’s intellectual ninety years ago or a fulfillment of the prophecies made by the city’s die-hard opponents like Zhou Zuoren 周作人, Shen Congwen 沈從文 and Gao Changqiao 高長橋? Or can this be in fact confirmation of Du Heng’s 杜衡 view expressed in 1935 that Shanghai was, for better or worse, the prototype for a future Chinese civilization? Is this then the ultimate, if belated, victory over its Jingpai 京派 enemies?. Sadly, such questions are not those that either Chinese intellectuals or Western scholars seem keen to explore. Yet, even if they did and regardless of their conclusions, it would mean little to the growing number of inhabitants of that bright, shiny world that is Shanghai Sub-urbia. |