|

|||||||||

|

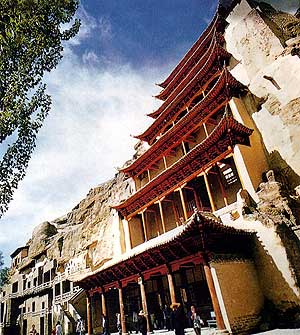

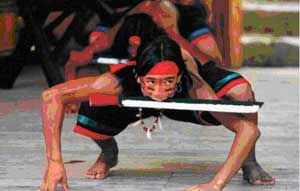

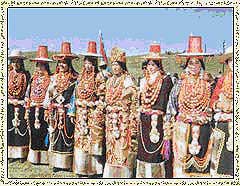

FEATURESCultural Heritage Properties of Qinghai, Gansu and Ningxia: Performance Items Fig.1 Yutu dance performed by Tu nationality, Tongren county, Qinghai. Apart from handicrafts, the 2006 intangible cultural heritage listing also includes customs, ceremonies and rituals. A number of heritage items in these categories from the north-west were also included: Fuxi rituals from Tianshui in Gansu; the Tu (Monguor) Nadun festival celebrated in Minhe county, Qinghai; Muslim national dress of Qinghai; traditional wedding celebrations of the Monguor (Tu) and Salar peoples; and the Repkong festival of the sixth lunar month celebrated in Tongren county, Qinghai. The latter is a complex listing designed to bring together many of the local Tibetan arts of Repkong, including thangka painting, drama, dance and singing, to name only the more obvious items. But the festival also includes contributions from other local groups, including the exorcistic dance of the Tu (Monguor) people called the Yutu dance. (Figs 1&2)  Fig.2 Yutu dance performed by Tu nationality, Tongren county, Qinghai. Performance items make up the bulk of the listings, although not all items with nominating local governments from the three north-western provinces, for example, Tibetan drama, shadow puppets and stilt walking, are unique to the north-west. Yet these three performing arts all acquired unique forms in the north-west. Stilt walking (cai gaoqiao), for example, can be seen in Spring Festival processions in rural settings in Shanxi, Liaoning, Gansu and other parts of China. Peasants clad in silk scholars' gowns or dressed as women walk on elevated stilts above the throngs of spectators, and through their costumes, partake in the spirit of 'inversion' that carnivals convey in so many world cultures. But the stilt walkers of Gansu walk on unusually high stilts that are often 3.3 m in height, and their art is considered the most difficult of its kind. Shadow puppet theatre (piyingxi) is a traditional entertainment throughout China, and it was probably introduced via the Silk Road at a very early date. The government is currently attempting to revive this art, and throughout June 2007 there is an exhibition of these puppets, with performances, in the National Gallery of China in Beijing. The government is also making concerted efforts to fund and subsidise performances across the country. Although shadow puppets have been losing out to cinema for more than half a century, shadow puppets remain amazingly resilient in Huanxian county, Gansu province, where there are more than 90 shadow play groups made up of farmers. Two major performance items from the north-west are: the Tibetan King Gesar epic, which extends throughout all areas of Tibetan, and Mongolian, cultural influence within China, and even to far-flung areas of the Republic of Mongolia and Siberia (such as, Buryatia, Kalmukia and Tuva); and, hua'er, which is the major folk song form of the north-west. We discuss the latter in a separate article in this issue. Below is a compendium of the other major performance items of the north-west. Hexi Baojuan ('Treasure Scrolls') Fig.3 A view of the Dunhuang caves Hexi baojuan is a genre of folk literature that melds recitation and singing. It once flourished along the Hexi Corridor of the Silk Road. Today, baojuan teeters on the brink of extinction, with only a handful of surviving practitioners, all now in their seventies. The genre termed baojuan emerged in the Yuan dynasty, according to Li Yu writing in the 2002:4 issue of Yindu xuekan (Yindu Journal, published by Anyang Normal University), and was derived from the sujiang ('plain tale') and bianwen ('serial texts') forms of Tang and Song dynasty popular literature, manuscripts of which have been recovered at Dunhuang. Following the Yuan dynasty, the Ming and Qing dynasties were also important periods in the subsequent development of baojuan forms and valuable manuscripts from this later period have also been recovered by 'literary archaeologists'. Baojuan first emerged from the popular tales that preaching monks used to illustrate Buddhist religious precepts, and so its original forms were shaped by sutras and sermons prepared in the Dunhuang area and in other Buddhist religious centres along the Silk Road during the Tang and Song dynasties. The genre of Hexi baojuan comprises tales couched in earthy language, but liberally punctuated with poetic verses sung in the poignant folk-singing style of Liangzhou. The narration advances the plot development, while the songs highlight the emotional incidents in the tales. The main subject matter of baojuan works was taken from Buddhist sutras and popular literature, especially Jataka stories, legends and folk tales. Cultural heritage authorities in the Liangzhou district of Wuwei have collected some 30 baojuan scrolls, mostly hand-written or printed using carved wooden blocks. More than 70 baojuan titles, and more than 140 copies of these, have been collected in Jiuquan. The last surviving practitioners of this musical folk literature form are also now being identified. [Nominated by the Liangzhou district of Wuwei city, Gansu province; and Suzhou district, Jiuquan city, Gansu province] The Epic of Larenbu and Jimensuo Fig.4 Dancers enact the epic of Larenbu and Jimensuo The rather unflattering ethnonym 'Tu' ('locals') is used today for an ethnic group, who prefer to style themselves the Monguor or the Chaghan Monguor. They are believed to be descendants of the Tuyuhun, an ethnic group who dominated the Silk Road running through Qinghai in the 7th and 8th centuries. They have assimilated Han, Tibetan, Mongolian and other neighbouring elements, but their spoken language belongs to the Mongolian branch of the Altaic language family. The Tu have no written alphabet, but Chinese and Tibetan alphabets are in common use, and a new Latinized script was created for them in 1979. They number nearly 200,000 and are concentrated in Minhe and Datong counties, as well as in their own Huzhu Autonomous County, all in eastern Qinghai province. Some Tu people can also be found in Ledu and Menyuan counties in Qinghai, as well as in the Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County in Gansu province. 'Larenbu and Jimensuo' is an epic folk poem, which has been passed down for generations. It recounts the tragic love story of a poor man, Larenbu, courting the daughter of a wealthy family. Larenbu is a serf engaged by Jimensuo's brother, who attempts with his wife to break up the couple. The tragedy comprises eight chapters of recitative, having elements of both singing and storytelling. The epic has variants in different areas. Marxist scholars argue that the epic connotes the transition from a nomadic to an agricultural society and lifestyle. Few practitioners can perform the epic today. [Nominated by Huzhu Tu Autonomous County, Qinghai province] Tibetan La-She Folk Songs Fig.5 Tibetan la-she performance on shores of Qinghai Lake. Tibetan la-she (Chinese transliteration: layi) is an antiphonal form of love song that is performed every summer in Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture on the southern shores of Kokonor (also Kokonur), better known today as Qinghai Lake. Sung in the Amdo dialect of the Tibetan language, which is concentrated in Qinghai but also widely spoken in Gansu and Sichuan, la-she also has other regional melodic varieties. These earthy songs are structured in a formal sequence, with a prologue, greetings, a passage of rhapsodic infatuation, an envoi and an epilogue. [Nominated by Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai province] The Gansu SuonaThe suona (also written in English as so-na and pronounced like the English for 'sauna') is a flared double-reed oboe that has spread throughout the Islamic world, although most Chinese regard it as emblematic of the culture of the loess highlands of Shaanxi province. Qinyang in Henan and Qingyang in Gansu, the nominating localities, do not represent the end points of the full geographic sweep of the traditional suona within China. Qinyang suona music of Henan province can be divided into two major schools according to locality and style, namely the Northern Qinyang and the Southern Qinyang, and one of the three families responsible for the Northern Qinyang suona school was surnamed Ma, suggesting Mohammedan antecedents. The Qingyang suona of the north-west remains popular, unlike the Qinyang variety in Henan province where its performance at weddings, celebratory gatherings and Buddhist temple events is now regarded as passé, and the Xifeng district of Gansu's Qingyang city, the political, economic and cultural centre of the city, can still boast more than 30 suona ensembles and 286 players. It is also popular in neighbouring counties, including Qingcheng, Huanxian, Heshui, Ningxian, Zhengning, and Zhengyuan. Most members of these north-western bands can in fact play a number of instruments. Ethnomusicologists, in their cataloguing fervour, have documented more than 1,200 traditional tunes in Qingyang suona, of which nearly half are included in 'Collection of Folk Instrumental Music in the Qingyang Area'. These suona bands cover a repertoire that includes instrumental traditional numbers, folk songs, and operetta pieces. But the suona bands are made up of 'oldies', and SACH describes the genre as being in danger of disappearing and in urgent need of protection. [Nominated by Qinyang city, Henan province, and Qingyang city, Gansu province] Muslim Folk Instrumental Music Fig.6 Hui men in national dress, Ningxia. Ningxia, located on the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River, has developed a culture assimilating elements from the Central Plains and the Western Regions (Serindia). With so many musical innovations flowing into China via Central Asia, a number of unique musical instruments have been developed in Ningxia; the wawu, mimi and kouxian, all instruments from Ningxia, evolved from the qiangdi (a kind of flute) and the huang (a kind of reed instrument). The substratum culture of Ningxia was predominantly Hui (Muslim), and this deference to halal has resulted in the local production of musical instruments fashioned to resemble the ox and the sheep, and Islamic motifs are used to decorate the instruments. Instruments are often inscribed with Arabic script. The beauty of this music long ensured its popularity, but Hui youths are now often unfamiliar even with the names of the instruments. The demise of many older musicians has rendered the future of this folk music precarious, and this type of music needs to be preserved for posterity. [Nominated by Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region] Quzi PerformanceThe quzi is a type of folksong which flourished in the Sui and Tang dynasties. Originating along the ancient Silk Road, manuscript versions of more than 500 such songs have been excavated from Dunhuang alone, as well as the titles of a further 70 or 80. Quzi was multi-ethnic in its origins and it inspired musicians and poets across China to create works within this genre. The length of the lines of most quzi are not fixed at the usual five or seven words, but are of uneven length. The quzi thus developed high-brow, middle-brow and low-brow forms at an early date. As high-brow poetry, the quzi was generally subsumed within the more general category of ci lyric poetry, and became a vehicle for more private and detached emotion. Writing in Lanzhou xuekan (2005:5), the academic Wan Weiwei provided 'A comparative study of Dunhuang quzi ci and Wen Tingyun's ci in their ways of conveying emotion' (Shilun Dunhuang quzi ci yu Wen Tingyun ci shuqing fangshi de bijiao). She demonstrated that the poetry of the Late-Tang writer Wen Tingyun (812-866) expressed the personal voice of the poet, as distinct from the Dunhuang quzi which were characterised by direct language and emotional content. Despite its social elevation to literati circles, new folksongs utilising the metres of quzi continued to be produced along the Hexi Corridor. The nomination of this cultural heritage item for listing envisages an archival project that will document the many outgrowths to the present day of a genre that first emerged in the Dunhuang area. [Nominated by Dunhuang city, Gansu province, and Huating county, Gansu province]Qinghai XianxiaoXianxiao is a folk art form in Qinghai and Gansu, related to one of the most influential local Tibetan-Han hybrid performance styles called in Chinese pingxian. Xianxiao in Chinese means literally 'virtue and filial piety', and it is named after the major content of the songs, forswearing evil and practising benevolence, while praising virtue and filial piety. The songs originally reflected a Confucian missionary zeal. Xianxiao in Qinghai has two major schools: Xining xianxiao and Hezhou xianxiao. The xianxiao in Xining features melodious tunes, while long works there are called 'grand biography' and these can extend over seven or eight nights. The Hezhou xianxiao originates in Linxia, Gansu province, bordering Qinghai province, and it is named because Linxia was called Hezhou in earlier times. The Hezhou xianxiao has been in circulation in Qinghai province for almost 100 years. In addition to historical and folk stories, the most famous contents of the Hezhou xianxiao are events from the modern history of Hezhou, such as the 'Hezhou Incident', the name for an uprising of the Salar and Hui nationalities. [Nominated by Wuwei city, Gansu province, and Linxia city, Gansu province] Guozhuang Dance Fig.7 Performance of Guozhuang dance (agricultural variety)  Fig.8 Performance of Guozhuang dance (temple variety) The name of the guozhuang dance is derived from the Tibetan word guozhuo, which means singing and dancing in a circle, and referred originally to campfire dances. The development of this type of dancing documents the spread of Tibetan tribes over the entire Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and into mountainous Yunnan. The dance has sacred and secular forms. Monastic guozhuang is organised for religious purposes in temples or monasteries, or for honouring a Living Buddha when he arrives at or leaves a temple or monastery. The secular forms are celebratory. The tempo alternates, and, at the beginning of a performance, men and women stand in two separate circles and sing in rotation, while swaying and stamping their feet. When their singing concludes, the pace quickens and ends with an exuberant allegro, which is often a compressed version of the preceding slow music. The movements of guozhuang are agile and vigorous. The loose, wide trousers of the male dancers resemble the feathered legs of eagles, and the men's movements are imitative of the eagle spreading its wings, hopping, and soaring. The emphasis falls both on postures and the expression of emotion. Women expose their right arms during dancing, with the right sleeve hanging loose. Moving around a circle, they sway their joined hands to the front and back, keeping pace with the beat, until late into the night. One of the groups nominating the guozhuang is Yushu (Ushug) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai province, but the dance is often included as a repertoire item in festivals in Repkong and other parts of Qinghai province, as well as at Labrang monastery and other Tibetan centres in western Gansu. [Nominated by Tibet Autonomous Region, and Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai province] Lanzhou Taiping Drums Fig.9 Taiping drums The Taiping ('Peace') Drum Dance of Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu province, is more than 600 years old. The drum used in the performance is cylindrical, measuring approximately 70 cm in height and 45 cm in diameter. The red cowhide skin of the drum is emblazoned with a picture of a dragon and a Taiji diagram encircled by the Eight Diagrams. The splendour of its performance is brought about not only by the intricate formations of the performing troupe, but also by the solo displays of individual drummers. Today, the Taiping Drum Dance is still very popular in the Lanzhou area, and teams perform at village temples during the Spring Festival. One theory concerning its origins maintains that it was introduced to Lanzhou by General Xu Da during the Ming dynasty. [Nominated by Lanzhou city, Gansu province] [Compiled by BGD with reference to several Chinese government websites, including www.bangnous.com] |