|

|||||||||

|

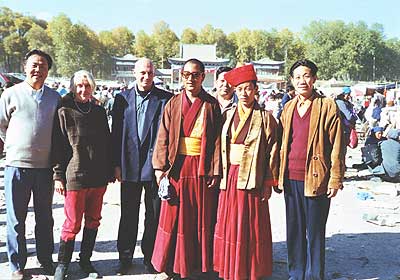

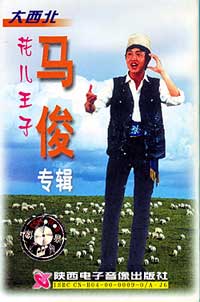

FEATURESSongs as Flowers: hua'er as Performance Fig.1 This crowd of approximately 1,500 is attending the hua'er festival in Guide county, Qinghai province. The festival in a large birch forest integrates elements of the traditional Tibetan picnic and the Muslim mart. Many of those attending set themselves up in groups along the river that runs through this forest eating noodles and drinking Tibetan barley wine, while others move through the forest from singer to singer. [BGD] Hua'er is the folk song form that today unites the Tibetan, Muslim, Han and other ethnic groups of China's north-west who live along what was the ancient Silk Road, and it can also be found among the Tungan people of Kirghizstan. However, the genre emerged among the ancient Huihui (Muslims), and survives today as a staple entertainment at fairs, song gatherings, temple fairs and Tibetan-style picnics through the northwest. The derivation of the term hua'er is contested, and sometimes these songs are called wild singing, or mountain songs. Hua'er festivals in Qinghai province bring together, as some of the contrastive participants, Tibetan girls in massive cowboy hats adorned with plastic flowers and Muslim men who dress like erstwhile Welsh coalminers. The hua'er pageant of Lotus Flower Mountain in Kangle county, Gansu province, lasts for six days and once attracted more than 100,000 people, but the festival is reportedly less patronized in recent years. Other major hua'er pageants are held at: Songmingyan in Hezhong county, Gansu province, a festival that originated in the Ming dynasty; Erlang mountain in Minxian county, Gansu, which features the Taomin style of singing and which was originally best characterised as a harvest festival; and Laoye mountain in Datong Hui-Tu Autonomous County, Qinghai, which features two versions of hua'er ballads—one spontaneous and the other comprising organized singing that appeared after 1949. Other pageants are held in Huzhu-Tu Autonomous County and in Minhe Hui-Tu Autonomous County, both in Qinghai, as well as in Ningxia and Gansu. A very famous hua'er festival is held at Qutan Temple (see: 'The Analysis of Narrative of the Murals of Qutan Temple', in this issue of CHQ), which is patronized largely by Tibetan and Han peoples.  Fig.2 View of crowd at hua'er festival in Guide county, Qinghai province. [BGD] In terms of singing technique, hua'er can be divided into two main schools: Hezhou-style hua'er and Tao-Min style hua'er. Hezhou-style hua'eroriginated in ancient Hezhou, what is today the Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture of Gansu province, and sometimes nicknamed China's 'Little Mecca'. Hua'er, and the Hezhou style of the musical genre, is also popularr in other areas inhabited today by Chinese Muslims (Datong Hui-Tu Autonomous County, Qinghai province; Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang region; and in the southern mountain areas of Ningxia region, including Xiji, Haiyuan, Guyuan and Jingyuan counties. For this reason, hua'er is often called 'the hua'er of the Muslims' or 'Muslim hua'er'. In Kirghizstan, hua'er is popular among the Donggan (Tung-kan) people who emigrated there from China after the failure of the 19th-century Muslim uprisings in Shaanxi and Gansu provinces, and there in several villages inhabited by descendants of these refugees. The northern Hui Muslims were the main transmitters of Hezhou-style hua'er, which is the genre's major form.  Fig.3 View of crowd at hua'er festival in Guide county, Qinghai province. [BGD] Scholars still disagree on when hua'er originated, but Wu Yulin maintains that the prosperity of the Huihui people under the Yuan dynasty of the Mongols provided the necessary conditions for the vigour of the genre. (See: Anthony Garnaut, 'The Islamic Heritage in China', CHQ, no. 5, March 2006.) The moving Mongol armies of the 13th century created Huihui forces, and large numbers of Muslim artisans and hangers-on accompanied the Mongol military machine. Yuan shi (History of the Yuan dynasty) cites the 'Huihui' ethnic group in more than 166 instances, far more references than appear in the later Ming shi (86 citations) and Qing shi gao (Draft history of the Qing, 29 citations). In the treatise on the Western Region (Xiyu zhuan) in Ming shi (History of the Ming dynasty), the following passage: 'In the Yuan period the Huihui were spread throughout, the country, but were more populous in Gansu'. Gansu at that time was more extensive than the present day province of the same name; at that time it included parts of Qinghai and Ningxia.  Fig.4 Gesang Bön (right), former deputy-head of Department of Culture of Qinghai province, with Living Buddha of Guide district (third from right) and assistant (second from right), with Xu Xinguo, head of Qinghai Archaeology Institute (first on left), Susan Dewar (second on left) and author (third from left) at hua'er festival in Guide county, Qinghai province. [BGD] 'The flourishing of an ethnic group is generally proportional to their political position', notes Wu Yulin, pointing out that within the 'racial' categories of the Yuan, Muslims and north-western peoples called Semu were ranked second to Mongols, with northern Chinese and Tungusic peoples occupying the third place, and southern Chinese the fourth. This favouring of Muslims over Chinese was reflected in the selection criteria for the public service examination system, enabling Muslims to occupy senior posts in the administration. According to Wu Yulin, this role in officialdom is reflected in hua'er that were still popular in the 1980s, and he cites an example: A big red bag and nine-dragon belt,  Fig.5 The male singers at the Guide hua'er festival tend to be Muslim, while the female singers are Tibetan. Although traditionally the men played instruments resembling the mandolin, today the accompaniment is pre-recorded and played on a ghetto blaster. [BGD] Xiliang prefecture was the name of Liangzhou, modern Wuwei in Gansu province, during the Five Dynasties and Tangut Xixia periods. The words of the song probably date from the Yuan dynasty. During both the Yuan and Ming dynasties, the north-west was an area of China that was developed through a policy of 'agricultural settlements' (called tun-tian), the core of which was formed by Muslim settlers. The hua'er songs of the Yuan settlers give the genre its feel today as 'country music'; when 'the thirteen provinces' ('shisan sheng') appears as a lyric in hua'er, it is not simply a conventional reference to China, though it could be in the Ming dynasty. Rather, it is a reference to the Yuan thirteen provinces that extend across the north and included Koryo (roughly equivalent to the territory of today's northern Korea).  Fig.6 'Best of hua'er tape from Qinghai. Tapes of recorded hua'er songs remain top-selling items throughout the north-western provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Ningxia, but also in Shaanxi and Shanxi. Official sales figures cannot reflect the massive number of pirated tapes that are sold. Singers rely for income on performance fees.  Fig.7 Ma Jun, a Dongxiang ethnic singer from Qinghai, came to public attention in 1986 and has subsequently performed in Beijing, Shanghai and other major centres. Known as the Prince of Hua'er, Ma became head of the Qinghai Hua'er Art Troupe, which has produced such well-known hua'er singers as Suonan Sunbin, Pengtso Joma, Cering Joma, Xiang Guo'an, Zhang Guodong and Wen Guilan. After the Yuan dynasty, the settlements played a punitive role in Chinese colonisation, one reminiscent of the labour camps of Qinghai province in the 1950s and 1960s. Chatting to hua'er devotees in the tiny Sichuan-style restaurants around Qinghai Lake, for example, one often discovers that the proprietors of these establishments did not come to Qinghai as part of the massive entrepreneurial diaspora from Sichuan that occurred in the 1980s. They came to the shores of Kokonur (Qinghai Lake) much earlier, fell in love with the land during their enforced sojourn, and decided to settle there when their sentences terminated. They also fell in love with hua'er, and this is why many hua'er songs have a tender, but bitter-sweet feel, analogous to the country blues of early 20th century southern USA.  Fig.8 Recording of Muslim epic Fifth Brother Ma and Sister Gadou as performed my Ma Jun and female virtuoso Ma Honglian (Bao'an nationality). The vocabulary in most hua'er reflects the Chinese dialects of the north-west. The word ganiu frequently appears in hua'er, and lexicographically it means 'calf'. But it is really the equivalent of 'baby' in the blues, and it reflects the fondness of the herdsmen for the offspring of their yaks. Similar affectionate diminutives are gamar ('pony') and gashour ('my baby's hands'). [BGD, © Bruce Gordon Doar] References:Zhang Yaxiong, An anthology of hua'er (Hua'er xuan), Beijing: Zhongguo Wenxian Chuban Gongsi, 1986. Zhao Zongfu, General discussion of hua'er (Hua'er tonglun), Xining: Qinghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1989. |