|

|||||||||

|

FEATURESOn Stage & Screen

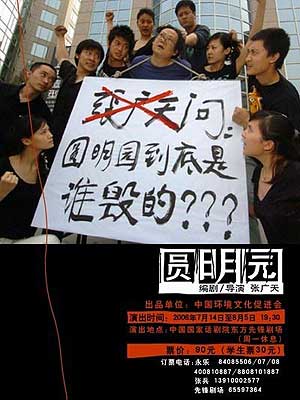

The year 2006 started off with a media controversy partially inspired by the attempt of Yuan Weishi, a Guangzhou-based historian, to encourage a more honest public account of the depredations of the Western powers in China in 1860 and 1900. Yuan argued that highly selective and ideologically-driven descriptions of events leading up to the infamous razing of the Garden of Perfect Brightness in 1860, and the Boxer rebellion of 1900, particularly in high school textbooks, were not only incorrect but served to inflame nationalistic passions among impressionable teenagers. Yuan also cautioned that the irrational spirit guiding history teaching in China undermined the country's ability to interact with the global community in a mature and rational manner.[1] While Yuan's objections to the simplistic accounts of late-Qing history were denounced by the party propaganda authorities as part of their more general curtailment of media diversity, in other cultural forums—in particular on the stage and in film—the Yuanming Yuan and the debates surrounding it were to engage new audiences during 2006. Yuanming Yuan: the playOver the years, the Garden of Perfect Brightness has featured in many films and teleseries. More recently, as the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), and in particular the late Qing the period from the end of the 18th century onwards, has increasingly featured in works of popular culture, the gardens too, and their fate, have figured more prominently in films and TV shows. Generally, however, cultural producers are vague, ill informed or purposely evasive in their depiction of how the Anglo-French Expeditionary Force of 1860 came to destroy the garden palaces of the imperial court. A recent example of this politics of avoidance is evident in the multi-episode teleseries about Prince Gong, the brother of the Xianfeng emperor, who negotiated a settlement with the foreign forces following the conflagration.[2]  Fig. 1 Poster for Zhang Guangtian's play, Yuanming Yuan. The director is posing as a counter-revolutionary being struggled by the cast of the play. The placard around his neck reads, 'Zhang Guangtian [crossed out] asks: Who really destroyed the Garden of Perfect Brightness?'. In the aftermath of the 'plastic sheeting' fiasco of 2005, the Shanghai-born director Zhang Guangtian created a theatre production called simply Yuanming Yuan. The play was staged at the National Avant-garde of the East Theatre in Beijing, 14 July to 5 August 2006. Zhang, who was the writer-director of the piece, is known for such controversial works as the raucous and slogan-ridden production Che Guevera (Qie.Guwala) in 2000, a play widely regarded as being one of the first theatrical works of China's cultural 'new left'. If nothing else, Che did garner the young director a measure of public notoriety, to which this new production about the destruction of the Garden of Perfect Brightness has only added. (Fig. 1) Building on the haranguing and pedagogical style of his earlier works, Zhang's Yuanming Yuan structurally also takes some inspiration from a theatrical style made popular among elite audiences in the mid 1980s when such plays as Wei Minglun's Pan Jinlian were staged to widespread acclaim. By employing one major controversial character, the playwright establishes a historical theme and a semi-autonomous commentator on the unfolding action. In the case of Zhang Guangtian's Yuanming Yuan, the protagonist is Gong Xiaogong, variously Gong Banlun, Gongye, or Master Gong in the play, although he also transmutes into various other characters. Gong acts both as trans-historical presence and foil, a key participant in the original destruction of the gardens and a critic on the plangent fate of the site up to the present day. Zhang's version of this now notorious 'traitor' is based on popular modern accounts of Gong (for more on these, see 'Gong Xiaogong and the Sacking of the Garden of Perfect Brightness' in the Features section of this issue). The director gives his character lines that reinforce his dubious politics:

The Yuanming Yuan that is presented in the play is nothing less than a man-made 'miracle' (qiji), a 'heaven on earth in which the East and West commingled' (Zhong Xi hebide renjian tiantang). Ironically, this other-worldly vision is also the creation of the Manchu rulers of the Qing who are depicted as debauched and corrupt invaders with no saving graces. Or rather, to use an old Maoist-era formulation that saved many heritage sites from despoliation, the garden is evoked as being 'the concrete expression of the creative genius of the labouring people' of China. No explanation is given as to why all Westerners invade the Celestial Capital despite its Manchu associations in 1860 or, indeed, why they plunder and then raze the garden palaces outside the city. Gong Xiaogong is represented as a canny thief of antiquities who disguises his infamy by enticing the foreigners to burn the place. He also justifies his actions by declaring self interest in the face of the corrupt rule of the Manchu-Qing, a theme taken directly from Wang Shuangzheng's novel Shock Awakening at the Garden of Perfect Brightness (again, see 'Gong Xiaogong' in Features). Meanwhile, at one point the pillage of the gardens is represented by a female actor who is bound to a cross and threatened with a meat cleaver by another actor.  Fig. 2 Bronze heads of the animals of a pig, monkey, tiger and bull, four of the Twelve Astrological Signs (shi'er shengxiao) used as fountain spouts at the Haiyan Tang, Western Pavilions, Yuanming Yuan. Repatriated by Poly Corp. The action of the play—one which is about the decline of the gardens—ignores the efforts to rebuild the palaces during the Tongzhi reign period, nor is any mention made of the dismantling of the remaining buildings of the Yuanming Yuan to construct the Yihe Yuan (Summer Palace) for the Empress Dowager in the late Guangxu reign. Instead, we skip to 1900 when another foreign army, the Eight Nations Expeditionary Army, invades the Chinese capital for no good reasons and lays waste to the remains of the gardens. In this mishmash of history and confused plotlines, the director presents his audience with a story of the demise of the gardens that speaks of the sacking of 1860 as the 'destruction by fire' (huojie), the 'pillage of wood' (mujie) in 1900 and the 'desecration of stone' (shijie) of the early Republic (1910s) when, as we have noted elsewhere, the gardens were used as a quarry for the public and private parks of the city. All of these depredations are blamed on concupiscence, as well as poverty resulting from misrule and folly. And the message is delivered in grandstanding speeches, as well as in saccharine poetry and rap songs.  Fig. 3 Copies of Haiyan Tang animals at Xieyanjie Street, Houhai, Beijing, winter 2006. Photo: GRB. The real aim of the director, apart from pointing an accusing finger at the Chinese who collectively finished off the job that the Anglo-French forces began in 1860, is to get to the 'plastic sheeting scandal' of 2004-2005. This part of the play, which provides at times a pointed social critique, touches on issues related to heritage matters in a stark and outspoken fashion. Indeed, apart from tapping into public interest in the Yuanming Yuan and the debates surrounding it, the central aim of the piece would seem to be the director's indictment of China's policies of rapid economic advancement and the concomitant environmental degradation and endangerment of the nation's fragile cultural heritage. These are matters that have become a matter of widespread concern among specialists as well as the general public in recent years, and the play, although stentorian in tone, confronted audiences with the incalculable costs of the country's burgeoning prosperity. To accomplish this task the director again calls on the services of Gong Xiaogong, as well as a host of other characters, including four of the Twelve Astrological Signs (shengxiao) of the Chinese calendar, a pig, monkey, lion and bull. These twelve figures featured as bronze sculptures in the elaborate Jesuit-designed fountain clock of the Haiyan Tang at the Western Pavilions. Plundered during the destruction of the Garden of Perfect Brightness, a number of the heads have in recent years been repatriated to China, having been acquired at international auctions. (Figs 2&3) The play reaches a moment of reflection with a tendentious quote from the Victor Hugo character who has featured as a Delphic presence throughout—the real Hugo having been the only notable Western writer to have publicly expressed outrange over the barbarity of the sacking of the gardens at the time (his letter of protest was written on 25 November 1861).[3] It is a text that is quoted ad nauseum by virtually all commentators and writers on the gardens in China. The long and rambling work finishes, however, with the whole cast joining in song to celebrate the 'lost paradise' and the 'national essence' of the gardens:

Fig. 4 A marble fragment, 1996. Photo: GRB Yuanming Yuan: the movie Fig. 5 Yuanming Yuan, DVD cover. CCTV, Beijing Science Educational Film Studio, Guangxi TV, 2006. The documentary film Yuanming Yuan, produced by the Beijing Science Educational Film Studio and released in 2006, was made on a far more lavish scale. As noted elsewhere, the destruction of the gardens first featured in Li Han-hsiang's Burning of the Yuanming Yuan (Huoshao Yuanming Yuan), an early co-production between Hong Kong and the mainland. A highly dramatic—and histrionic—feature film, it also proved to be very popular at the box office, as well as being the recipient of a Ministry of Culture award. For that production, a series of to-scale copies of some of the Western Pavilions, in particular the much-imitated 'View of Distant Seas' (Yuanying Guan), were built outside Beijing. Computer-generated effects have rendered such concrete reconstructions otiose. (Fig. 6) Made in the style of many contemporary historical documentary films—a style that favours the admixture of historical narrative with costume drama and reenactments—the director Jin Tiemu's Yuanming Yuan boasted a budget of nearly 10 million yuan and is said to have been years in the making. It was also hailed in the Chinese media for technical wizardry, featuring 35 minutes of digital reconstructions of sections of the Yuanming Yuan gardens, designed by the Beijing Ruizhi Shengyang Technical Company. (Figs 7&8)  Fig. 6 The technical crew preparing 3-D imaging material for Jin Tiemu's Yuanming yuan. Source: Zhongguo yichan (China Heritage), 2006:9, p.70.  Fig. 7 A virtually reconstructed peony garden as used in the film Yuanming Yuan, recalling the fact that the Kangxi emperor had presented his son Yinzhen (later the Yongzheng emperor) with a Peony Terrace just north of his residence at Changchun Yuan. The Peony Terrace formed the basis for the Yuanming Yuan.  Fig. 8 The digitally-reconstructed 'Fanghu Shengjing', the realm of the immortals which juts into the lakes near the Western Pavilions from the film Yuanming Yuan. Premièring at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on 8 September 2006, and in tandem with a book of the same name, the film advertised itself as an 'epic' (shishi), the Chinese equivalent of an 'instant classic'. Jin Tiemu, who was both director and screen writer, told a journalist that the film 'aims to present the royal palace as a shining pearl in the crown of the whole human civilization in a realistic fashion to both Chinese and overseas audiences.' (Fig. 9) On 23 September 2006, China Daily also reported Jin as saying that, 'The epic-like documentary reflects my interpretation of a tragic and thought-provoking moment in Chinese history.' Jin, whose successful 'signature documentary' An Army Reborn had offered a new interpretation of the Qin army, went on to say that,

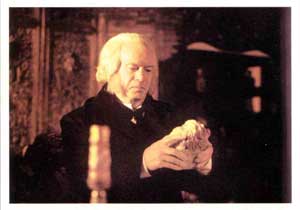

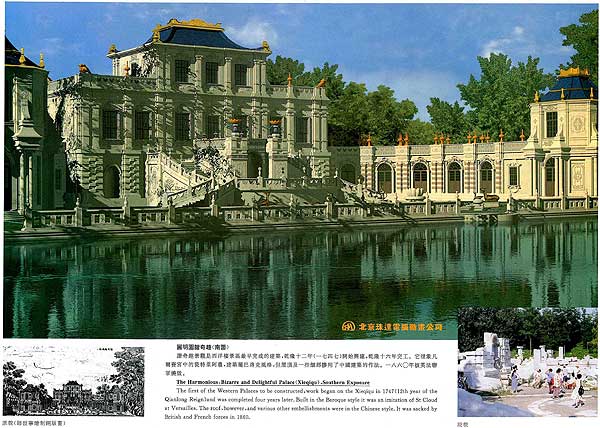

Rejecting the accusations that he made a work that stirred patriotic ire, he also remarked that the documentary was 'made for moviegoers around the globe and my film is based on every historical record available. It is not a fictional movie. It is an honest, cool-headed account of history'. (Fig. 10)  Fig. 9 Jin Tiemu directing the scene 'First City Under Heaven' (Tianxia diyi cheng) for Yuanming yuan on location in Xianghe, Hebei province. Source: Zhongguo yichan (China Heritage), 2006:9, p.61. The film does have certain strengths, presenting to a broader public information familiar to scholars of the history of the gardens. The Lei family builders are introduced and a detailed description of the tangyang (models) and drawings they made for the throne is given (see Articles in this issue). The opulent digital reconstructions of palaces, sites and pavilions, along with quotations from Jesuit missionary accounts, add both detail and colour to this accessible film. Digital technology also allows the makers to recreate the Western Pavilions in perhaps the most compelling, if fleeting, fashion to date (and that includes the generally brutish imitations of the buildings found around the country).  Fig. 10 Foreign extras in the scene 'Battle for Baliqiao' in Yuanming yuan. Source: Zhongguo yichan (China Heritage), 2006:9, p.67.  Fig. 11 James Bruce, Lord Elgin, in an 'alas poor Yoric moment', played by a foreign extra in Jin Tiemu's Yuanming yuan. Source: Zhongguo yichan (China Heritage), 2006:9, p.68. As is usual with such productions, however, the foreigners whose stories are intermeshed with the history of the place are by and large presented clumsily; this is something that results from bad writing and direction, as well as being the inevitable result of relying on the services of miscellaneous foreign residents in China. In Yuanming Yuan this is as true in the case of the more sympathetically depicted Jesuits missionary/artists who worked as designers for the Western Pavilions in the Qianlong court as it is for the invading Anglo-French army of 1860, including James Bruce, Lord Elgin, commander of the British forces. And, as in popular accounts of the sacking of the gardens, the story presented is highly elliptical. Furthermore, since Jin has relied on British accounts, the French (and one black soldier in particular) end up being the villains of the piece. (Fig. 11) Similarly, as with most grand historical documentaries with a didactic purpose, Jin Tiemu lays claim to years of painstaking research and strict historical accuracy. While the foreign involvement with the garden is given both a positive and negative assessment, the director for all his research completely overlooks the important elements of non-Han culture in the design and layout of the gardens, and the role they played in the creation of a symbolic representation of the whole Manchu-Qing empire, not merely its Ming-era Han territory. Too often Yuanming Yuan, all dressed up in romantic and melodramatic garb as it is, speaks to its audience through a portentous, sometimes mellifluous, voiceover. Although it was reported that the final touches to the digital effects of the film were added by the New Zealand-based company Weta Digital, the extensive use of Beijing-generated computer imagery in this and many other recent historical films, feature and documentary, shows that imaginative and virtual cultural heritage flourishes in China. [GRB]  Fig. 12 'Harmonizing the Strange and Delightful' (Xieqiqu), a hybrid Sino-Western building at the Western Pavilions. This digital reconstruction was made by the Zhuda Computer Company, Beijing, 1996. Long before the recent digital 'imagineering' of Yuanming Yuan, the Zhuda Company in Beijing (Beijing Zhuda diannao donghua gongsi), as well as the designer Wang Lifeng of Xingxing Computer Graphics and the Media Graphics Interdisciplinary Centre of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, were rebuilding parts of the gardens in the mid 1990s. Notes:[1] For both Chinese and English versions of Yuan's essay, 'Modernization and History Textbooks', see www.zonaeuropa.com/20060126_1.htm". Yuan Weishi does, however, stop short of providing crucial historical detail regarding the real reasons behind the sacking of the Garden of Perfect Brightness. See also Barmé, 'A Year of Some Significance', published as 'Historical Distortions' in the Review Supplement of The Australian Financial Review, 31 March 2006. Reprinted by UC Berkeley's China Digital Times (Zhongguo shuzi shidai), with notes, at: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2006/04/a_year_of_some_significance_geremie_r_barme.php [2] Prince Gong: a life in servitude (Gong qinwang: yi sheng wei nu) in 42 episodes, Guangzhou: Guangdong Oriental Media Group, 2005. [3] Victor Hugo's letter was reprinted in the UNESCO Courier, November 1985, and can be found online at: http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1310/is_1985_Nov/ai_4003606. |