|

|||||||||

|

FEATURESIslamic Calligraphy in China

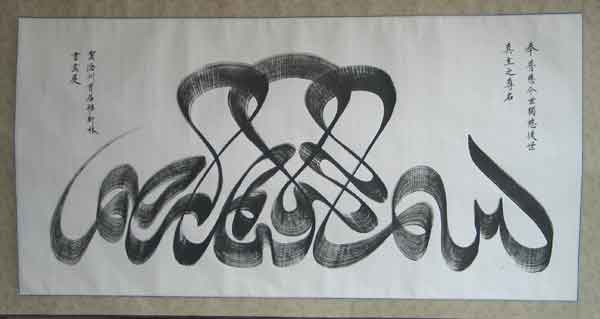

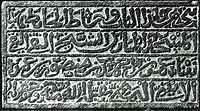

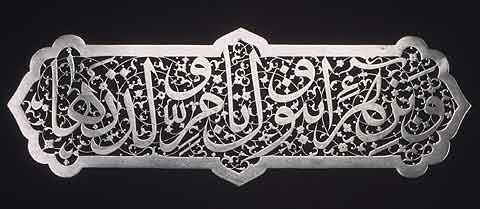

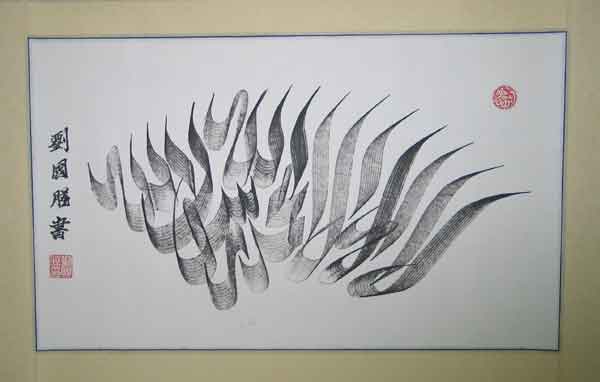

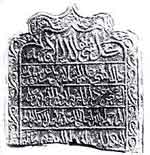

Fig. 1 Invocation drawn in a single stroke, by Ma Jinhua, Cangzhou, Hebei, 2002. "In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful." From the collection of the Cangzhou West Mosque. [AHG]  Quanzhou Zongjiao Shike, plate A17.1]" border=0 /> Quanzhou Zongjiao Shike, plate A17.1]" border=0 />Fig. 2a Stone inscription in Kufi script, 14th century, Quanzhou. The text reads, "And the places of worship are for God alone: so invoke not anyone along with God." (Quran 72:18). [ Quanzhou Zongjiao Shike, plate A17.1]  Fig. 2b Stone inscription in Thuluth script, obverse of Fig. 2a. The text reads, "The entrance and walls of this auspicious mosque were built by the venerable, sincere and pure Nayna Umar bin Ahmad bin Mansur bin Umar of Alabayni (in Yemen). May God satisfy his wishes and show him mercy." Calligraphy is one of the most prestigious art forms in Islamic and in Chinese culture. This may stem from the particular status accorded to canonical and foundational texts, namely the Quran and the Confucian canon, during the classical periods of their respective art histories. According to Islamic mythology, the Chinese invented the pen, and it was from China that fine paper was first brought into the Islamic world. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that unique forms of Islamic calligraphy have emerged in China.  Fig. 3 Five cursive scripts. The top two scripts are those most commonly used for decorative motifs in mosques. Design by Muhammad Sakkal, 1997. There are many different styles of calligraphy used in writing Arabic. Kufi script, named after the town of Kufa in southern Iraq that was the Islamic capital in the caliphate of Ali, was the first of the styles to develop. The straight lines and sharp angles of kufi are especially suited to working with hard materials, such as the hide on which early Quran manuscripts were written and the carved stone of early mosque decoration. New, rounded styles of calligraphy such as naskh and thuluth developed from the 11th century, when the use of fine paper became widespread. (Figs 2, 3 & 4) The writing implement favoured by Arabic calligraphers is the wooden or reed pen, whittled to a nib of a thickness and width that varies according to the calligraphic style. Before cheap printed books turned hand-copying into a quaint art in the first half of the twentieth century, quill making was one of the first skills that students at Islamic madrasas were required to master. Up until fifty years ago, madrasa students in Hezhou, Gansu, would not begin formal lessons until they had written out proper copies of their textbooks. Despite the availability of a range of hair brushes used for Chinese calligraphy, the basic implements used for hand-copying Islamic texts in China remained much the same as those used in Iran or Egypt. The same is the case for the choice of paper, despite the availability in China of fine paper of many different grades, hard parchment remained the material of choice for copying manuscripts.  Fig. 4 Cut steel plaque in Thuluth script, 17th century. The word "thuluth" means "of three", being the ratio of the height of the curved part of the letter to the letter as a whole. Original in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, see http://www.metmuseum.org/Works_of_Art/viewOne.asp?dep=14&viewmode=0&item=1987.14, accessed March 2006. ![Fig. 5 Brushes and pens used by the calligraphy artist Tang Shulin of Jilin. [Tang Shulin]](005/_pix/chn5calligbrushes.jpg) Fig. 5 Brushes and pens used by the calligraphy artist Tang Shulin of Jilin. [Tang Shulin] ![Fig. 5a Work table of Tang Shulin, showing brushes and blocks of Chinese ink. [Tang Shulin]](005/_pix/chn5calligbrushink.jpg) Fig. 5a Work table of Tang Shulin, showing brushes and blocks of Chinese ink. [Tang Shulin] While hand-copying texts provided (and still provides) the basic training for students of Islamic calligraphy, a myriad of ornamental and decorative forms of Arabic script were developed by masters of the art. Timurid stone architecture and documents of the Ottoman court represent two high points in the evolution of Arabic calligraphy as a decorative art. The writing implements and material used for ornamental calligraphy have not been standardised as they have been in the practice of hand-copying texts. In addition to the reed pen, short bristled brushes and wooden spatulas are commonly used, and many materials can be embellished with calligraphic motifs: fine paper, wood, stone and porcelain. Nevertheless, being the foundation of calligraphic artistry, hand-copying of texts defines many of the formal characteristics of decorative calligraphy. Ornamental Islamic calligraphy in China today is most commonly written on fine paper using a wooden spatula or a broad, short-bristled brush. (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6 Fan tasmiya (invocation) by Liu Shengguo. "In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful." Original at the West Mosque, Cangzhou, Hebei. [AHG] Sini Script![Fig. 7 <i>Tasmiya</i> in Sini script. Original at the West Mosque, Cangzhou, Hebei. [AHG]](005/_pix/chn5calligChineseTasmiya2.jpg)

Fig. 7 Tasmiya in Sini script. Original at the West Mosque, Cangzhou, Hebei. [AHG]  Fig. 8 Peacock fan motif on cloth, by Chen Jinhui. The Arabic script in the centre is the profession of faith, "There is no god but God; Muhammad is the Messenger of God." The gold script in the four corners records the names of the four archangels. [Chen Jinhui] Of the many forms of Islamic calligraphy in China, there is one that can be properly described as a formal style. This is referred to by Chinese Muslim calligraphers as simply the Chinese or Sini script. Although this word can be used for any distinctly Chinese forms of Islamic calligraphy, Sini specifically refers to a rounded, flowing script, whose letters are distinguished by the use of thick and tapered effects. This is the script used for the placards bearing the tasmiya or invocation that almost invariably hangs above the main entrance or from a roof beam of the prayer hall in mosques in eastern China. It is also often used to write the shahada (profession of faith) in the form of a peacock fan placed in the centre of the mihrab (niche indicating the direction of prayer). (Fig. 8)  Fig. 9 Postage stamp issued by the Pakistan Postal Service to commemorate the Fourth International Calligraphy and Calligraphic Art Exhibition and Competition held in Lahor, Pakistan, on October 1, 2004. The media release that accompanied the stamp issue announced that the competition was prompted by the desire of the President of Pakistan to project the soft face of that nation internationally. See,

http://www.pakpost.gov.pk/philately/stamps2004/ international_art.html, accessed March 2006.

Fig. 9 Postage stamp issued by the Pakistan Postal Service to commemorate the Fourth International Calligraphy and Calligraphic Art Exhibition and Competition held in Lahor, Pakistan, on October 1, 2004. The media release that accompanied the stamp issue announced that the competition was prompted by the desire of the President of Pakistan to project the soft face of that nation internationally. See,

http://www.pakpost.gov.pk/philately/stamps2004/ international_art.html, accessed March 2006.

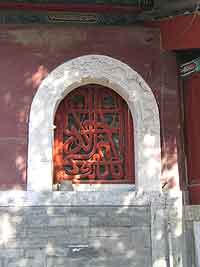

The origins of the script have not been the subject of academic research, nor have its features been formally set down in writing by any Chinese calligrapher. As a starting point, it should be pointed out that it closely resembles the cursive Thuluth script that was popular in Persia and central Asia during the Mongol Ilkhan period (14th century CE). More recently, works by several of China's leading Arabic calligraphers, including Chen Jinhui and Sha Jinying, were entered in the Fourth International Calligraphy and Calligraphic Art Exhibition and Competition held in Pakistan, 2004. (Fig. 9) None of the works in Sini script received any approbation, something understood in China as proof that the judges did not understand the formal features of the script or recognise it as a distinct style.  Fig. 10 Tombstone with Thuluth script, Quanzhou, 14th century, "Everything will perish except His face". (Quran 28:88) The Prophet, peace be upon him, said: "He who dies in a foreign land dies a martyr. He has departed this ethereal world and has entered the world of joy, and joined the Merciful God. Here lies Sadr Ajil Kabir." [ Quanzhou zongjiao shike, plate A92.1] The Origins of Sini ScriptIn the flourishing of Islamic artistic expression that followed the consolidation of Mongol control over China, Persia and central Asia in the late 13th century, the Thuluth cursive script became the standard script used for the invocations inscribed in the inner walls of mosques and for verse headings of the Quran. Judging by the Arabic stone inscriptions from this period that have been found at Quanzhou, China was not an exception to this trend. (Fig. 10 ) ![Fig. 11 <i>Tasmiya</i> placard by Sha Jinying, placed above the <i>mihrab</i> of the West Mosque, Cangzhou. [AHG]](005/_pix/chn5calligMihradTasmiya.jpg) Fig. 11 Tasmiya placard by Sha Jinying, placed above the mihrab of the West Mosque, Cangzhou. [AHG]  Fig 12 Shahada placard above the entrance to the Beiwu mosque, Dachang, Hebei. Note the swastika-like motifs drawn on the two lines of square rafters above the placard, which each read "God is great" in Kufi script. This calligraphic motif is found in a number of variations in India and Iran, and appears on the flag of the Islamic Republic of Iran. [AHG]  Fig. 13 Calligraphic window decoration in Sini script, Niujie Mosque, Beijing. This window is in the oldest section of the mosque that was first built in the Jin dynasty (1115-1234 CE), though the design of this window decoration probably dates from one of the major renovations of the mosque in the early Qing. [AHG]  mihrab of the Dingxian mosque, Hebei. [Zhongguo Yisilanjiao jianzhu]" border=0 /> mihrab of the Dingxian mosque, Hebei. [Zhongguo Yisilanjiao jianzhu]" border=0 />Fig. 14 "There is no god but God...." Peacock fan motif in Sini script in the mihrab of the Dingxian mosque, Hebei. [Zhongguo Yisilanjiao jianzhu] Today, Sini script is used almost universally in tasmiya placards in mosques in eastern China, but is less common in the north-western provinces of Shaanxi and Gansu. I am not aware of any examples of the script from the far western province of Xinjiang that pre-date the Qing conquest of the region in the mid-18th century. (Figs 11, 12 & 13) This geographic distribution corresponds to the region under the direct control of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Trade and travel restrictions during the Ming period broke the intimate links that had existed under Mongol rule between the Muslim communities of China and those of central Asia and Persia. It is from around the Ming period that distinct Chinese Islamic traditions of writing began to develop, including the practice of writing Chinese using the Arabic script (xiaojing) and distinctly Chinese forms of decorative calligraphy. The early examples of Sini script that may go as far back as the first two centuries of the Ming dynasty can be found, for example, in the mihrab of the Niujie mosque in Beijing and the Dingxian mosque in Hebei province, though precise dating of the decorative motifs used in mosques is difficult given the universal use of timber that requires major renovations every hundred years or so. The examples of decorative calligraphy shown in this article reveal a modest departure from the conventions of Thuluth script, though the slender ankles and fat feet of Sini script are beginning to show. (Fig. 14) Examples of decorative script from the early 18th century show the same basic characteristics of Sini script as it is practised today. An exaggerated form of the Sini script was popular in central China in the beginning of the twentieth century, though excellent renditions of the form dating from this same period can be found in mosques today. (Fig. 15) ![Fig. 15 Placard in Sini script by Riyaduddin (Ma Yuanzhang), Zhangjiachuan, Gansu, c.1919. [AHG]](005/_pix/chn5calligRiyaduddinMaYuanz.jpg) Fig. 15 Placard in Sini script by Riyaduddin (Ma Yuanzhang), Zhangjiachuan, Gansu, c.1919. [AHG] The placard begins, "Why holdest thou to be forbidden that which Allah has made lawful to thee?" (Quran 66:1) Creative Variations on a ThemeWhile Arabic writing is most readily distinguished by the flowing tails of its letters, Chinese characters are neatly contained within a square form. Chinese temples and houses are often adorned with a hanging couplet placed to the left and right of the main entrance, and a four-character phrase above the door. Chinese buildings are square and symmetrical in design, and these features are complemented by the squareness of the characters used in the entrance way and by their symmetrical arrangement. Chinese mosques usually have Arabic placards in flowing Sini script above their entrance ways. However, on either side of the entrance, one often finds a pair of hadith or lines from the Quran in Sini script hedged into the form of the Chinese-character couplet, hanging in a string of seven or nine diamonds. This arrangement looks strange to the eye of someone familiar with Arabic decorative art in central Asia or Iran, but looks perfectly natural to Chinese eyes accustomed to reading words boxed into a square. The rotation of the square form of the Chinese character by forty-five degrees to form a diamond is a universal practice amongst Chinese Muslims, and may be an aesthetic choice that resonates with the arrangement commonly found on Chinese doors of the character for fu ("luck") on a diamond background, or it may reflect a conscious departure from the Chinese aesthetic veneration of the square. Chinese Muslims will also tend to place a square tea tray at an angle of forty-five degrees to a square room or table. Another common form of Sini calligraphy is rectangular, with one of the names of God or the Prophet wrapped around an extended vertical stroke such as the alif or "a" of the phrase Ya Mustafa (O Chosen One!). (Fig. 16) Alif is used as an architectonic device in much Arabic calligraphy. This form can be compared to popular Chinese calligraphic representations of the characters for dragon, tiger and longevity, which also employ a single vertical stroke (Fig. 17). The Sini script is also used for calligraphic art, which uses words to draw representations of objects. Calligraphic art is produced throughout the world. The distinct feature of the Chinese practice is simply the style of the script used, and here again the exaggerated curves and lithe strokes of Sini script are in evidence. Acknowledgements: My thanks to the Cangzhou West Mosque collection in Hebei for many of the calligraphic works used to illustrate this essay. I am also grateful to Bai Zhuren, Zhang Han and Zhang Enbo of Cangzhou for providing me with an excellent introduction to Sini-script calligraphy. [AHG] ![Fig. 16 'Ya Mustafa' (O Chosen One!), a favourite name for the Prophet Muhammad). Calligraphic painting in the form of a Chinese 'grass script' or <i>cao shu</i> character, by Ma Donghua. Original at the West Mosque, Cangzhou, Hebei. [AHG]](005/_pix/chn5calligYaMustafa.jpg) Fig. 16 "Ya Mustafa" ("O Chosen One!", a favourite name for the Prophet Muhammad). Calligraphic painting in the form of a Chinese "grass script" or cao shu character, by Ma Donghua. Original at the West Mosque, Cangzhou, Hebei. [AHG]  Fig. 17 An ancient Chinese calligraphic rendition of the character hu (tiger). The emphasis placed on the single downstroke is common in Chinese calligraphic paintings of single characters. References:Chen Jinhui, Chen Jinhui Alabowen shufa xuan (Selected Arabic calligraphic works of Chen Jinhua), Beijing: Zhongguo Minzu Sheying Yishu Chubanshe, 2002. Liu Zhiping, Zhongguo Yisilanjiao jianzhu (Islamic architecture in China), Urumqi: Xinjiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1985. This book was published in 1985 on the basis of a manuscript prepared on the eve of the Cultural Revolution in 1965. While some mosques survived the Cultural Revolution, very few of the placards and other examples of calligraphic arts that adorned the mosques did, making this book one of the few sources available for the study of historical examples of ornamental art used in Chinese mosques. Tang Shulin, Tang Shulin awen shuhua yishu ji (Selected works of Arabic calligraphy paintings of Tang Shulin), Beijing: Minzu Chubanshe, 2000. |