|

|||||||||||

|

FEATURESFrom the Editor's DeskWilliam Sima Australian Centre on China in the World

Assessments of The China Critic, and in particular its promotion of liberalism and cosmopolitanism in the Shanghai publishing milieu, have tended to focus upon the weekly journal's most famous cultural commentators, men generally noted for having an enduring influence on Chinese intellectual and literary history. The legacy of such 'cross-cultural' writers as Hu Shih 胡適, Lin Yutang 林語堂, Quentin Pan 潘光旦 and Pearl Buck and Emily Hahn in turn is largely what has given rise to the reputation of The China Critic's as a 'liberal' and 'cosmopolitan' Shanghai institution. Little, however, has been said of figures such as Chang Hsin-hai 張歆海, D.K. Lieu 劉大鈞 and Kwei Chung-shu 桂中樞, the three men credited with being the actual editors of The China Critic during its fourteen-year history. Compared to such iconic writers as those mentioned above, the editors have left a much smaller mark on Chinese publishing and cultural history (making it difficult even to determine the year of Kwei Chung-shu's death). Nonetheless, they were at least nominally in charge of The China Critic's editorial direction. A Janus MienThe precise roles of those named Editors, and indeed of the Managing Editor, Contributing Editors and Associate Editors—positions which changed frequently over time—is not entirely clear. Special Articles in The China Critic were written by identified contributors, and most of the columns which came and went over the years—Quentin Pan's Book Review, Lin Yutang's The Little Critic, Wen Yuanning's 溫愿寧 Unofficial Biographies (later re-titled Intimate Portraits) and Lin Yu's 林幽 Oversea Chinese, to name four—were attributed to their respective editors. When the editorship of such columns changed (The Little Critic, for instance, was overseen by the philosopher T.K. Chuan 全增嘏 when Lin Yutang was on leave) it was duly acknowledged. But the Editorials section, which in a typical issue consisted of three or four short lead columns and one or two longer commentaries, appeared without attribution. Determining their authorship is therefore a speculative endeavour at best. A close reading of the journal does, however, suggest that editorial apologism if not outright support for the Nanjing government's often egregious political transgressions coexisted with a genuine liberal impulse, found most often in the writings of Lin Yutang. As I demonstrate below, this was the 'Janus mien' of The China Critic. When we examine the changing membership of the journal's editorial group, it is immediately evident that, practically and often intellectually, The China Critic shared close quarters with the Nationalist government. Elsewhere Shuang Shen has commented on this connection in relation to the newspaper's financial backing:

The China Critic's sources of income remain unclear. It is conceivable that advertising revenue and subscriptions might have sustained the newspaper for over a decade, but the important question of editorial independence deserves closer attention regardless of funding sources. Chang Hsin-hai and D.K. Lieu both reduced and eventually ended their involvement with The China Critic because of the call of officialdom: Chang resigned as founding editor after little under a month to join the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and Lieu was active in so many government financial and statistical bureaus, committees and delegationsthat it is remarkable that he found as much time as he did to write for The China Critic. He would withdraw as editor in April 1930, ostensibly because his government work kept him away from Shanghai. It is noteworthy, however, that his resignation came just two weeks after a particularly scathing essay by Lin Yutang landed The Critic in hot water with Nanjing. After Lieu stepped down, the position of Editor disappeared without explanation until March 1933, when Kwei Chung-shu took on the mantle and kept it for the rest of the newspaper's life. In Eugene Lubot's assessment quoted at length in 'The Critic at Work' section of Features, The China Critic represents'the general liberal perspective, and its modification with time' in early Republican China. In his account, the journal began in 1928 with 'a characteristic liberal stance', but as the 1930s progressed it 'felt the ever-increasing pull of patriotism' due to the threat and, later, violent reality of Japanese territorial encroachment. Eventually, the journal 'gravitat[ed] into orbit around the government.'[2] Abundant evidence can be found to confirm Lubot's thesis, such as the sycophantic Special Article from November 1938, which the then-editor Kwei Chung-shu apparently saw fit to print:

Toasting a Free but Not a Slanderous PressThe more one reads of The China Critic—in particularthose editorials that comment on contemporary affairs—the more it becomes apparent that the oft-evoked independent and liberal stance of the publication was, from the start, something of a pretense, or at least fungible. Consider 'The Toast for a Free Press', an editorial from July 1929 in which the writer comments upon a speech by Gideon A. Lyon, a correspondent for the Washington Star, at a function held by the Daily Press Association of Shanghai. Lyon had proposed a toast for a 'free press, a responsible press and an unhampered court of justice in China', while also condemning Nanjing's recent order to deport Hallett Abend, a correspondent for The New York Times, on charges of 'repeatedly [making] slanderous comments on the National Government and the various national leaders during the past nine months.' The unnamed editor who wrote this piece (most likely D.K. Lieu, the named editor at the time) endorses Lyon's toast for press freedom 'in general principle', before supporting the order for Abend's deportation:

'In general principle' might as well stand for the qualifying editorial stance The China Critic took on a number of issue involving the Nanjing government's abuses of power. As we will see below, Chang Hsin-hai, D.K. Lieu and Kwei Chung-shu variously toed the official line and at times shied away from The Critic's purported liberal principles. Upon closer examination, Chang and Lieu in particular appear to be self-serving career men. When Lin Yutang condemned the government's demolition of slum housing in Nanjing (the city underwent some Potemkin-village-like beautification on the eve of a Danish royal visit) in March 1930, then-editor D.K. Lieu whitewashed the affair in a manner that was certainly anathema to the kind of liberal humanism and independence from government influence that The China Critic claimed to represent; and, when Chang was sent to represent China in Portugal in 1933, Lin (whose reputation as The Little Critic was by now well established) ridiculed him as a man 'sent abroad to lie on behalf of his country' (a famous quotation from the early English diplomat Sir Henry Wotton dating from 1604). As such internal conflicts as these suggest, The China Critic's contributors were members of a coherent 'group' (pai 派 or she 社—indeed, Zhongguo pinglun zhoubao she 中國評論週報社 was frequently used in publishing and subscription advertisements) only in so far as they formed a coterie of writers who published in the pages for the same newspaper. As the following accounts of The China Critic's editors suggest, however, English proficiency and an early experience of studying overseas did not always a liberal or cosmopolitan make. Notes:[1] Shuang Shen, Cosmopolitan Publics: Anglophone Print Culture in Semi-colonial Shanghai, New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2009, p.33 [2] Eugene Lubot, Liberalism in an Illiberal Age: New Culture Liberals in Republican China, 1919-1937, Westport, Connecticut and London, England: Greenwood Press, 1982, pp.90 & 94. (We have included Lubot's full discussion of The China Critic in this issue, see here). Lubot defines the liberal perspective in the Introduction to his book in the following way:

[3] George S.S. Young, 'Japan Slams China's "Open Door" ', The China Critic, XXIII:7 (17 November 1938): 104-107 [4] 'The Toast for A Free Press', The China Critic, II:29 (18 July 1929): 567-568. Emphasis added. The Other China CriticsChang Hsin-hai (張歆海, 1898-1972) Fig.1 Chang Hsin-hai's portrait in Who's Who in China, 1936 H.H. Chang was an educator and diplomat, and his many literary and journalistic pursuits included his role as founding editor of The China Critic.[Fig.1] He was born in Shanghai, where he received his early education, and in 1916 he received a Tsinghua College scholarship to study in the United States. He completed a Bachelor of Arts degree at Johns Hopkins University in 1919, a Master of Arts at Harvard in 1920, where he also went on to attain a doctoral degree in English Literature in 1922 for a thesis titled 'Matthew Arnold and the Humanistic View of Life'. Like Lin Yutang, who also studied at Harvard around this time, Chang was influenced by the literary critic Irving Babbitt; but he also developed a particular interest in Indo-European linguistics, studying Gothic, Anglo-Saxon, Middle English and High German. In 1921, Chang acted as an attaché to the Chinese delegation at the Washington Naval Conference and, after touring Europe in the mid-1920s, he returned to China where he served for a short time as faculty chairman and Professor of English Literature at Peking University (1926-1927). In 1928, he became Director of the European and American Department of the Nationalist government's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a position he held until 1933.[1] The back-cover blurb of Chang's 1944 biography of Chiang Kai-shek notes that, among his various achievements, he 'founded and edited China Critic, the most widely read Chinese weekly in the English language.'[2] In reality, his editorship was short-lived: in late June 1928, less than one month after the magazine commenced publication, Chang took up employment with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Nanjing.[Fig.2] Thereafter, his association with The China Critic was merely that of a Contributing Editor.  Fig.2 Chang Hsin-hai resigns as editor, 28 June 1928

'The Educational Conference At Nanking' was one of Chang Hsin-hai's few special articles in The China Critic. While he was listed as a contributing editor until January 1935, it appears that his association with the weekly essentially ceased with the commencement of his official appointment. Many other contributing editors of The China Critic were, however, listed for years after their actual involvement with the journal ceased (Lin Yutang and Quentin Pan, for instance, were credited as being contributing editors from 1928 until 1945, even though neither wrote anything for The Critic after 1934 and 1936, respectively). Chang worked at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in China until 1933. From 1933 until 1937 he represented the government as Minister Plenipotentiary to Portugal, Poland and Czechoslovakia. Apparently a bona fide Party Man by the time of his appointment to Portugal, The China Critic's founder and erstwhile editor was ridiculed by Lin Yutang in his essay 'An Open Letter to H.E. Chang Hsin-hai, The New Minister to Portugal':

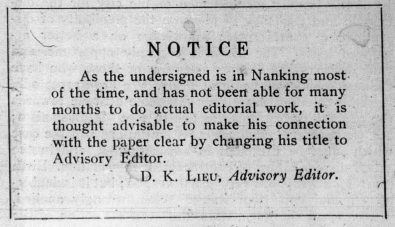

After four years as a diplomat Chang returned to China in 1937 and taught Western literature at Nanjing University until 1940. That year, he moved to the United States where he promoted the Chinese war effort and engaged in further diplomatic work throughout the 1940s. In the 1950s and 1960s, he was a researcher and teacher at Long Island University (New York state) and Farleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey.[3] Chang's 1956 historical novel The Fabulous Concubine, which is set against the backdrop of the Boxer Rebellion at the turn of the twentieth century, is distinctly reminiscent of Lin Yutang's earlier Moment in Peking (1939). Chang's last book America and China: A New Approach to Asia (1965) is a treatise addressing the importance of establishing relations between the United States and the People's Republic. During his US sojourn Chang also wrote for various notable American publications including The Atlantic Monthly, The North American Review and The Nation. Chang Hsin-hai died in Shanghai in 1972. D.K. Lieu (劉大鈞, 1891-1962) Fig.3 D.K. Lieu in Who's Who, 1936 A prominent economist and statistician of Republican China, Dakuin K. Lieu was also the nephew of the late-Qing writer Liu E (劉鶚, z. 鐵雲, 1857-1909), most famous for his 1907 satirical novel The Travels of Lao Can 老殘遊記. Born in Huai'an 淮安 in northern Jiangsu province, Lieu studied under private tutors until 1905, whereupon he went to Shanghai to attend the YMCA School; he then attended the Imperial University (now Peking University). Lieu studied economics at Michigan University from 1911, graduating with a bachelor degree in 1915. In 1916, he returned to China to become a professor of economics at Tsinghua University and, from 1920 until 1928, he lead the research and investigation department of the Bureau of Economic Information of the Beiping government.[Fig.3] Like many intellectuals of the time, and indeed many of those associated with The China Critic, the establishment of the Nanjing government lured Liu south.[4] In the 1936 edition of Who's Who in China, a compendium of prominent political and intellectual leaders, D.K. Lieu is credited as being 'a prime factor in establishing The China Critic, of which he was editor for five years.'[5]He was involved with The China Critic from the started and named as a Contributing Editor from the first issue (to which he contributed the special article 'Japan's Status in Shantung'). After Chang Hsin-hai resigned as Editor, Lieu took his place. He remained editor until 10 April 1930, when he became an Advisory Editor.[Fig.4]  Fig.4 D.K. Lieu resigns as editor, 10 April 1930

Lieu's resignation as editor came two weeks after Lin Yutang wrote 'The Danish Crown Prince Incident and Official Publicity', possibly the most politically controversial essay ever printed in The China Critic. Lieu's insistence upon reiterating the newspaper's mantra of journalistic integrity and independence from official and commercial influence appears to have been directly connected with this event.[Fig.5]Lin'sessay, a 'special article' rather than a 'Little Critic' piece (this column did not appear until July 1930), referred to a scandal involving the government's denial of demolishing of slum housing in central Nanjing in preparation for a Danish royal visit:  Fig.5 D.K. Lieu reiterates The China Critic's policy of impartiality and freedom from government interference, 17 April 1930

Accompanying Lin's essay in the same issue was the editorial 'Face Saving For the Nation', one of the more odious examples of The China Critic's defence of the Nanjing government.Not only does the editor (likely D.K. Lieu) hide behind Lin's tongue-in-cheek claim of 'reluctance to pass judgment'—Lin claims to withhold from moral judgment only because he fears retaliation, and he condemns the government anyway—he goes on to defend national face as something 'meritorious' and 'inherent in [the Chinese] system'; something more worthy of saving than the homes of the poor, who, according to Lin, the police drove into the rain without prior warning:

Fig.6 Toddler Cai Quandong 蔡全東 stands amidst what remains of his wrecked home, one of hundreds in Sanya's largest slum district forcibly evacuated and demolished during the 2011 Spring Festival. The slums were demolished to make way for a new tourist complex. Phoenix News, 13 February 2012

Qian Suoqiao has noted that Lin Yutang's essay 'The Danish Crown Prince Incident and Official Publicity' was not well received in Nanjing. As Lin reminisced many years later, after it was printed 'K.P. Chu, the manager of The China Critic, immediately took the night train [to Nanjing], apologized and promised to behave like a good citizen for the good of the country.'[6] While there is no way of ascertaining the extent to which this brush with officialdom affected The China Critic's editorial policy, it is interesting to note that the position of a single 'editor' disappeared from the day of D.K. Lieu's resignation, only to be restored three years later after the controversy had died down.[Fig.6] During this hiatus, Lieu and Kwei Chung-shu were credited as being Advisory Editor and Managing Editor, respectively. By this time D.K. Lieu 'as one of China's two foremost authorities' in finance and economics and with increasing demands on his time, divested himself of his main association with The China Critic to become a Contributing Editor,[Fig.7] a position he (nominally) retained until the journal's demise in December 1945.  Fig.7 'Mr. D.K. Lieu's Resignation', 30 March 1933  Fig.8 The Editorial Board on the day of Lieu's resignation, 10 April 1930. The China Critic had no single named Editor again until March 1933 There were indeed many demands on D.K. Lieu's time during the late 1920s and 1930s.[Fig.8] In July 1928, he acted as an expert member of the National Financial Conference held by the Ministry of Finance, and he was also made Director of the Bureau of Statistics of the Legislative Yuan in December that year. Beginning in 1931, he became President of the Chinese Statistical Society, and was re-elected to that office in 1934. (He was also the Chinese government delegate to the international statistical conferences held in Tokyo in 1930 and Madrid in 1931.) In the 1930s, D.K. Lieu also served as an economist with the Shanghai Commercial and Savings Bank, an adviser to the Domestic and Foreign Debt Consolidation Commission and a member of the planning commissions of the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of industry.[7] In addition to editorials that D.K. Lieu may have written for The China Critic, he also produced a large number of special articles, the majority of which presented the results of surveys of industrial and agricultural development and currency reform. One exception is the early essay 'Chinese Calligraphy', in which Lieu offers some comments about this unique art form, and about how a restrictive 'foreign alphabet'—presumably the Latin alphabet, but Lieu offers no clues—prevented the development of a creative equivalent anywhere outside of China:

Fig.9 Advertisement for China's Tennant Farming Economy 我國佃農經濟狀況 in The China Critic, 8 January 1931 D.K. Lieu's forte, however, was not letters but numbers. His November 1930 special article 'Statistical Work Under the National Government' is a more representative contribution. In it he offers a broad summary of the surveys with which he was engaged during the early 1930s. As mentioned above, while The China Critic often carried the names of many of its contributing editors on its masthead long after they had left, articles by D.K. Lieu continued to appear on occasion until the end of the 1930s. 'Economic Development of China's Southwest' (July 1939) is an example of a late contribution, written when Lieu was serving as head of the National Military Committee Economic Research Department, and probably residing in Chongqing:

Apart from his contributions to The China Critic, from the late 1920s Lieu also wrote a number of economic studies in both Chinese and English, including China's Tennant Farming Economy 我國佃農經濟狀況(1929), Foreign Investments in China (1930), Report on Chinese Industry 中國工業調查報告 (1937) and The Silk Reeling Industry in Shanghai (1940).[Fig.9] From 1941, Lieu held posts as both the head of Chongqing University Business College, and of the Special Economic Research Committee of the Central Bank; after the war he served on the policy drafting committee for the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was enacted in 1947, and soon after this time as an attaché to the Bureau of Economics of the National Government in the United States.[8] D.K. Lieu died in New York in 1962. Kwei Chung-shu (桂中樞, 1897-1987) Fig.10 Kwei Chung-shu in Who's Who, 1936 Kwei Chung-shu was born in Kai county 開縣 Sichuan province, which is today part of the greater Chongqing municipality. He was a journalist, lawyer and businessman.After graduating from Tsinghua College in 1919, he earned a Bachelor of Arts from Lawrence College (Wisconsin) in 1920, a Bachelor of Journalism from the University of Wisconsin in 1921 and, years later, a Bachelor of Law from the Comparative Law School of China in 1933.[Fig.10] Unlike many of his colleagues who returned to teaching positions in China shortly after studying abroad, following graduation C.S. Kwei stayed in the United States and worked as a journalist until 1925. In the years 1919-1920 he was an associate editor at Far Eastern Republic, a San Francisco-based English-language monthly published by the Chinese National Welfare Society of America; he wrote from the Wisconsin State Journal in 1921, The New York Times and New York Evening Post during the Washington Disarmament Conference of 1921-1922, and was the longest-serving Editor-in-Chief of the New York-based The Chinese Students' Monthly 中國留美學生月報, from November 1922 until June 1925. As if to anticipate The China Critic group by almost six years, contributing writers to The Chinese Students' Monthly during these years of Kwei's editorship in fact included The Critic's very own T.K. Chuan (who wrote 'An Essay on Errors' in April 1924) and Quentin Pan (who contributed 'Evaluation of Chinese Student Fraternities in America' in June 1925). Lowe Ch'uan-hua 駱傳華, who was credited as one of The China Critic's 'Contributing Editors' from January 1933 until December 1945, was particularly active at Students' Monthly during this time, contributing a number of essay during Kwei's time as editor.[9] After returning to China, Kwei managed the Shanghai office of the Government Bureau of Economic Information (1926-1928) and, apart from becoming a key member of The China Critic group, he was also a regular contributing writer to The Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury.[10]Plain Speaking on Japan, Kwei's first book, was in fact a collection of Evening Post essays on Sino-Japanese problems.[Fig.11] Edward Y.K. Kwong's 鄺耀坤 November 1932 review commented that:

Fig.11 Advertisement for Kwei's Plain Speaking on Japan, 26 January 1933

Kwei also edited the inaugural edition of The Chinese Year Book (1936), a tome-like double-volume work consisting of surveys on topics ranging from economics, politics and telecommunications, to physical culture, cooperative movements, periodical and newspaper publishing statistics—topics that were frequently discussed in the pages of The China Critic.[Fig.12] In his foreword to the first volume the noted thinker and educator Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培, 1868-1940) described itin the following way:  Fig.12 Title page of The Chinese Year Book  Fig.13 The calligraphy of H.H. Kung 孔祥熙, then vice-president of the Executive Yuan and Minister of Finance, frontispiece to the first issue of The Chinese Year Book, 1936

Kwei was the only member of The China Critic whose work appeared consistently in the weekly throughout its existence, and he wrote on a wide variety of topics. He was credited as Managing Editorfrom the first issue, and remained in this position throughout the editorship both of Chang Hsin-hai and D.K. Lieu. His first special article, 'Dr. Hu Shih and Slogans', appeared on 20 September 1928. In it he presented a critique of Hu Shih's 'The Religion of Names', which had appeared the week before:

Kwei also took exception to Lin Yutang's ideas about humour. Shortly after Lin published the essay 'Chinese Realism and Humour' in late September 1930—this essay was Lin's first discussion of humour in The China Critic—Kwei responded with 'Where is China's Sense of Humour':

From 30 March 1933, when D.K. Lieu stepped down as Advisory Editor and the position of Editor was reinstated, Kwei was credited as sole Editor of The China Critic until its final issue of 27 December 1945. While the difference between these various editorial titles is not entirely clear, Kwei was publically perceived as a leading figure in The China Critic from at least as early as November 1932, when Madame Sun Yat-sen 宋慶齡 castigated 'Mr. Kwei and his fellow intellectuals' for their lackluster defence of Chen Duxiu 陳獨秀 (see the editorial 'Chen Tu Hsiu') after the founder and erstwhile leader of the Chinese Communist Party was arrestedby Nanjing officials:

Fig.14 The China Critic's editorial board, 23 August 1945

When The China Critic returned to print in August 1945 after a five-year interruption, Kwei was the only founding member of the editorial group who remained.[Fig.14] He returned as editor and his presence was evident in a number of special articles—'Merciful Killing', a considered justification of the use of the atomic bomb against the Japanese, appeared in the first issue of the reissued journal. During this final year of publication, Kwei also produced a volume of war poetry (待旦樓詩詞稿).[Fig.15]  Fig.15 Advertisement for Kwei's book

Kwei was in Hong Kong by the early 1950s, and for a time he wrote for highly successful English-language newspaper The Standard.[12] He spent much of the rest of his life to developing computing input systems for Chinese characters and, in 1979, he published a study Kwei's Video Codes for Chinese Characters with The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong. C.S. Kwei died in Hong Kong in 1987.[13] P.K. Chu (朱少屏, 1882-1942) Fig.16 P.K. Chu in the 1936 edition of Who's Who in China An early Republican revolutionary, journalist, educator, entrepreneur, as well as a diplomat in later life, P.K. Chu served as the Business Managerof The China Critic from its founding in May 1928, until publication was interrupted during the war in November 1940.[Fig.16] He was murdered by Japanese forces in Manila in April 1942. P.K. Chu was born in Shanghai where he received his early education at Nanyang Public School 南洋公學 (known today as Jiaotong University 交通大學), where he stayed on to teach after graduating. In 1903, he went to study in Japan, where he became a founding member of the Tongmenghui同盟會, a revolutionary organization established by Sun Yat-sen in Tokyo in 1905. He returned to China just as the Japanese government began banning Chinese insurgent activities. Following the establishment of the Provisional Government of the Republic of China in 1912, Chu serve briefly as a secretary to Sun Yat-sen. In 1906, he taught classes at Jianxing Public School 健行公學 which had been established that same year by Gao Xu 高旭, another founding member of the Tongmenghui. In November 1909, the revolutionary literary group South Society 南社 was established at Tiger Hill 虎丘 in Suzhou. Chu was one of seventeen—fourteen of whom were members of Tongmenghui—present at the Society's inaugural meeting, and he served as its accountant.[Fig.17] Around this time Chu also became involved in revolutionary newspapers started byYu Youren 于右任; from 1920 to 1924 he the European correspondent of Shenbao 申報.[14]  Fig.17 The seventeen founding members of the South Society pose during their inaugural meeting, on 13 November 1909. P.K. Chui is standing, fourth from the right

Chu also became involved with the World Chinese Student's Federation寰球中國學生會, a Shanghai-based association which recruited and aided Chinese students intending to study abroad. The Federation was established in 1905 by Li Denghui 李登輝, who was later the first president of Fudan University. In 1916, Chu became its general secretary, remaining in that position until the late 1930s.[Fig.18] Under Chu's leadership, the Federation established a number of night and polytechnic schools that offered vocational training in typewriting, accounting and sewing. Although the Federation's activities as a student recruitment organization ceased when P.K. Chu left Shanghai in 1939, a number of schools including the Huanqiu Elementary School 寰球小學 and Night Education School 補習學校 survived until the mid 1950s.[15] It appears that P.K. Chu never wrote for The China Critic, but in his capacity as both an educator and the journal's business manager, he made efforts to promote its use in educational institutions, and he ran advertisements in its pages for Federation-sponsored schools. In one advertisement published in 1937 and 1938, Chu is credited as being the principal of the Huanqiu English-Chinese Typewriting School (Huanqiu yinghua dazi ke 寰球英華打字科).[Fig.19]  Fig.18 P.K. Chu offers The China Critic subscription discounts for educational institutions, 3 January 1929  Fig.19 'How should you make use of your summer break?' An advertisement for the Huanqiu typewriting polytechnic school 寰球英華打字科, headed by principal P.K. Chu 朱少屏, The China Critic's Business Manager, 23 June 1938 In the early days of the war with Japan Chu was instrumental in the creation of the International Cosmopolitan Club. On 21 October 1937, a short report titled 'Cosmopolitan Club Formed' listed Shanghai University president Herman C.E. Liu (劉湛恩, 1896-1938) as the head of this organization, and P.K. Chu as one of its vice-presidents. Commenting on the formation of the club, and of the assassination of Herman Liu five months later, Zeng Jingzhong 曾景忠 writes that an attempt was also made on P.K. Chu's life:

The China Critic reported Herman Liu's death in the editorial 'Herman C.E. Liu' on 14 April. A brief follow-up column in the 'News of the Week' section on 5 May, 'Prisoner Confesses to Dr. Liu Murder', noted the verdict of a hearing in Shanghai's First Special District Court was that 'the assassination was instigated by one Lin Yu-pu, a leader of a pro-Japanese terrorist group'. I have scoured the pages of The China Critic to find a report of the attempt on P.K. Chu's life—it carried reports of attacks on civilians and public officials almost every week following the outbreak of the war—but it would appear that none was ever printed. It is also curious that the newspaper made no note of P.K. Chu's appointment to the Philippines in late 1939 or early 1940. P.K. Chu was killed in April 1942 following the Japanese invasion of the Philippines along with nine other Chinese diplomats serving at the consulate. The China Critic printed an 'In Memoriam' dedicated to him in September 1945:

Fig.20 A motorcade carrying the bodies of the nine diplomats passes through Xinjiekou 新街口 in central Nanjing, September 1947

Chu's remains, along with those of the other eight diplomats who perished in the Philippines, were recovered and returned to China in September 1947.[Fig.20] They were buried at Juhuatai 菊花台 in Nanjing. Earlier that year, The China Daily and a number of other newspapers reported that P.K. Chu's son, Zhu Kangsheng 朱康生, visited the burial ground of the nine martyrs to pay respects to his father on the occasion of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War.[17][Fig.21]  Fig.21 Zhu Kangsheng touring the Nine Martyrs Historical Exhibit 九烈士史科陳列館 in Nanjing, April 2012

Notes:[1] Who's Who in China, Shanghai: The China Weekly Review, 1936, pp.8-9; Donald Abenheim and James Ryan, 'Register of the Chang Hsin-hai Papers,' Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Archives, 1977 (1998 reprint). Online at: http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf567nb0mz/. [2] Chiang Kai-shek: Asia's Man of Destiny, New York: Doubleday, Doran and Company, Inc., 1944. [3] 'Register of the Chang Hsin-hai Papers', op. cit. [4] Who's Who in China, op. cit., pp.171-172. [5] Ibid. [6] Qian Suoqiao, 'Discovering Humour in Modern China: The Launching of the Analects Fortnightly Journal and the "Year of Humour" (1933)', in Jocelyn Chey and Jessica Milner Davis, eds, Humour in Chinese Life and Letters, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011, p.204. The author cites Lin Yutang's Memoirs of an Octogenarian, Taipei: Mei Ya, 1975, p.70. [7] Who's Who in China, pp.170-171; Sun Zhijun 孫智君, 'Liu Dajun de chanye jingji sixiang shuping' 劉大鈞的產業思想經濟述評 (Summary of the Liu Dajun's Thought on Industrial Economy), Zhongnan jingji zhengfa daxue xuebao 中南經濟政法大學學報(Journal of Zhongnan University of Economics and Law), no.3 (2007): 117-122. [8] 'Summary of Liu Dajun's Economic Thought', op.cit. [9] The Chinese Students' Monthly, 1906-1931: A Grand Table of Contents, Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, Center for Chinese Research Materials, 1974, pp.54-63. I thank Christopher Rea for bringing this to my attention. [10] Who's Who in China, pp.127-128. [11] Kwei Chungshu, ed., The Chinese Year Book, Shanghai, 1936. (Nendeln, Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1968), p.xiii. [12] Alan Castro, 'Tiger Roars for HK', The Standard, 26 March 1999. Online at: http://www.thestandard.com.hk/news_detail.asp?pp_cat=&art_id=25913&sid=&con_type=1&d_str=19990326&sear_year=1999. [13] Zhongguo changjiang sanxia da cidian 中國長江三峽大辭典, Hubei: Shaonian Ertong Chubanshe, 1995. [14] Who's Who in China, p.66; and, Zeng Jingzhong 曾景忠, 'Zhu Shaoping yu nanshe' 朱少屏与南社 (P.K. Chu and the South Society), Dang'an yu shixue 檔案与史学 , no.2, 2003: 32-38 [15] Wang Kaifeng 王開峰 and Sun Yun 孫雲, 'Bainian liuxuechao zhong de huanqiu zhongguo xueshenghui' 百年留學潮中的寰球中國學生會 (The World Chinese Student's Federation and a Century of Chinese Students Abroad), Xinmin wanbao 新民晚報, 26 February 2012. Online at: http://xmwb.xinmin.cn/html/2012-02/26/content_29_1.htm [16] 'P.K. Chu and the South Society,' p.38. [17] See 'Kangri waijiao lieshi Zhu Shaoping zhi zi, 8 xun Tianjin laoren fu Nanjing jifu' 抗日外交烈士朱少屏之子,8旬天津老人赴南京祭父 (Octogenarian son of Zhu Shaoping, Diplomat and Martyr of the Japanese Resistance, Travels from Tianjin to Nanjing in Honour of his Father), Zhongguo ribao 中國日報, 6 April 2012. Online at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/hqpl/zggc/2012-04-06/content_5622478.html. |