FEATURES

The China Critic - 1932 | China Heritage Quarterly

The China Critic: a Chronology

William Sima

Australian Centre on China in the World

William Sima, whose research into the history and contents of The China Critic led to this combined issue of China Heritage Quarterly, has created a Chronology of the weekly. It follows the progress of The Critic from its first appearance in May 1928 through the highs and lows of the 'Nanjing Decade', and then through its various wartime permutations.

Will's Chronology, which is arranged by year below, accounts for the changing fate, and the friable editorial stance, of The Critic. It also provides numerous links to the articles under discussion allowing for them to be appreciated in an historical context.—The Editor

1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1945

1932

4 February

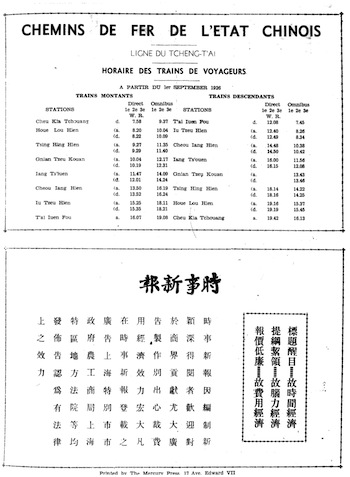

Fig.1 A French-language train schedule and a Chinese advertisement for the China Times 時事新報, 14 January

One week after the Japanese invasion of Shanghai, an event known as the 'January 28 Incident' 一二八松滬, The China Critic begins a series of issues dedicated to exposing what this week's headline editorial calls 'A War in Disguise', commenting upon the reaction of the international community to Japanese aggression in China.

The editorial 'Japan Attacks Shanghai' describes the atmosphere at this time, and endorses the Shanghai Municipal Council's decision to accept the Japanese ultimatum:

To be sure, for the past two weeks the whole world as been viewing with grave concern the so-called Shanghai situation yet nobody has ever suspected that it would assume such alarming proportions. In fact, for a while, we were almost led to believe that there was no cause for worry, especially after the news had been handed out in the afternoon of [January] 28 that the Mayor of the Municipality of Greater Shanghai had unconditionally accepted the four demands of the Japanese. This action undertaken by the Mayor was laudatory, in view of the fact that it must have taken a great deal of courage on his part to agree to those demands, thus to invite adverse criticism not only from people who are connected with the anti-Japanese movement, but from those who are in sympathy with it.

A notice at the end of the articles section reads: 'Due to the situation in Shanghai, the China Critic is obliged to suspend for the time being the following departments: “The Little Critic”, “Book Review”, and “Arts and Letters”. Further, the Critic can not guarantee its readers prompt and safe delivery of the magazine until such a time when peace and order is fully restored in the city.'

In the coming weeks 'Tales of Woe' depicts the plight of citizens caught up in the attack. Editorials and articles focus primarily on, and commentary of the 4 March League of Nations resolution to this conflict. 'Little Critic' and 'Book Review' resume on 7 April.

(Read 'Tales of Woe' and 'So-Desuka!', by O.D. Rasmussen, from the issue of 18 February.)

17 March

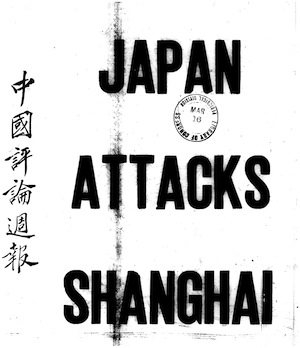

Fig.2 The front cover of The China Critic, 4 February

Fig.3 The cover of the 10 March issue

Sinologists, particularly those in Australia, are widely aware of the annual George E. Morrison lecture series, which commenced in 1932. In this issue The China Critic supplied an editorial endorsement of the inauguration of this series. This column givesa brief background of the impetus of establishing the lectureship, and of its namesake, commenting on the wider significance of institutions such as the Morrison Lecture:

There is urgent need of a better understanding between Chinese and other nations of the world, particularly those speaking the English language, and we trust that through this Lectureship leaders of thought and culture may be invited to meet similar leaders in Australia for mutual benefit.

5 May

This week, Lin Yu 林幽introduces his 'Oversea Chinese' column in an essay titled 'By Way of Introduction':

This column is dedicated to the promotion of the welfare of our overseas brethren. We shall devote our attention to their glorious achievements as well as to the grievous treatments they now receive, to the actual conditions, under which they now live, as well as to the problems which they are now facing.

(Qian Suoqiao's 錢鎖橋 essay 'The Critic Gentlemen', in the 'Features' section of this issue, discusses Lin Yu and this column in further detail).

12 May

In 'Book Review' this week, Quentin Pan reviews China's Own Critics, a collection of essays by Hu Shih and Lin Yutang, with commentaries by Wang Jingwei 汪精衛. Hu's essays appeared previously in Chinese, primarily in New Moon 新月; Lin Yutang's are drawn exclusively from 'Little Critic'. Pan offers the following appraisal:

All these essays are, as the editor Mr. Tang has remarked in his preface, 'intellectually and morally refreshing.' Though written two or three years ago, none of them is out of date. [The questions they raise] are still being constantly asked, and more insistent now than ever. Mr. Wang's commentaries are equally interesting, in that they betray very noticeably how the mind of a doctrinaire infallibly works, particularly when attempting to show that the doctrine with which he is identified is infallible.

(Tang Liangli's 湯良禮 'Preface' to China's Own Critics is included in the 'Features' section of this issue.)

22 September

The Editorial 'A Chinese Humorous Fortnightly' endorses the launching of Analects Fortnightly 論語半月刊, Lin Yutang's magazine devoted to the literary principle he called 'humour' (youmo 幽默). Many essays published in the new magazine were translations of pieces that Lin and othershad written for the 'Little Critic' column. In keeping with the humorous style of generousself-ridicule that Analects Fortnightly would come to represent, the writer remarks that:

So much depends upon the humour of our censors, but even if it fails, we should regard it as a valuable education in humour for our rulers… . The proof-reading [of Analects] is atrocious, but we are not sure but [sic] some of the typographical errors are part of the humour the readers bargain for.

27 October

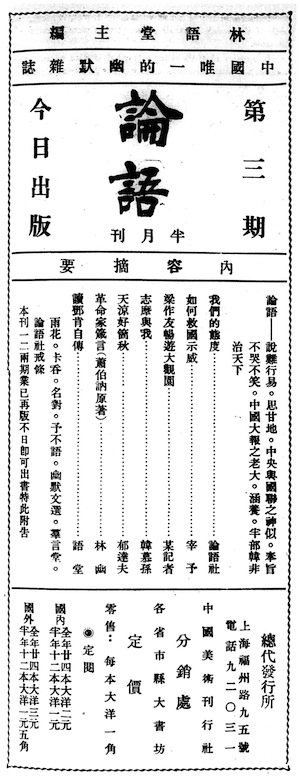

Fig.4 Advertisement for the third issue of Analects Fortnightly, 20 October

The infamous arrest on 17 October of the founder and former leader of the Communist Party, Chen Duxiu 陳獨秀, is an important event this year. The editorial 'Chen Tu-hsiu' describes the background of his arrest, and The China Critic's reaction:

While Mr. Chen has actually at some time been involved in plots for overthrowing the Kuomintang regime, it should be remembered to his credit that he denounced the present communist party in no uncertain terms, calling their troops bandits. While not sharing his political views, and perhaps because we do not share his political views, it seems to us that the wisest course would be for the National Government to show the most lenient consideration of Mr. Chen's case, and accord to him the most liberal interpretation of his constitutional rights to hold different opinions, as is acknowledged in most modern countries.

3 November

Chen's arrest prompted Madame Sun Yat-sen宋慶齡to appeal to China's intellectuals to form an organization to defend civil liberties.Those at The China Critic find themselves in the uncomfortable position of having to concede (and confront) Kuomintang censorship of a leftist figure.

'Madame Sun's Statement on Civic Liberty' is printed in this week's 'Public Forum' column. Madame Sun invites 'all the intellectuals of China, and all friends of the Chinese people' to aid in the formation of a 'committee in defence of all political prisoners, all victims of the [Kuomintang] Terror'. She strongly condemns 'Men like Kwei Chung-shu and his fellow intellectuals'—that is, The China Critic group, with Kwei as their editor—for 'remaining silent' during previous government crackdowns on leftist intellectuals. Regarding the case of Chen Duxiu specifically, she criticizes The Critic on the following grounds, with reference to last week's Editorial:

Those who have come to the defence of Mr. Chen, his Chinese friends, and such organs as the Shanghai Times, the Journal de Changhai and The China Critic, have done so largely on the grounds thatMr. Chen has disassociated himself from the revolutionary movement and because, according to these papers, he has called Communists 'bandits.'

The Editorial 'Civic Liberties Union' responds in the following way:

The difference of opinion between Madame Sun and our editorial of the last issue was perhaps real, but we nevertheless endorse her proposal for the formation of a general committee in defense of victims of justice… . The real value of its work, however, consists in teaching our people a new attitude of self-defense and, may we say, of active resistance, against injustice. Unless the people of China take a new attitude of self-defense, the so-called government by law will not fall down from heaven like so much manna in a desert for the Israelites.

1 December

This week's 'Little Critic' carries the title 'I Like to Talk with Women'. Like many of the essays Lin Yutang wrote for this column it is styled as a 'comment' on or an 'appreciation' of modern life. Other topics that have attracted Lin's attention include the joys of smoking cigarettes, the frustrations of owning a car or moving into a new apartment—but this week, the source of his enjoyment is talking with women. Lin starts out by declaring that 'it must not be referred that I am a misogynist', but goes on to say:

I like women as they are, without any romanticizing and without any bitter disillusionment. With all their contradictions, light-mindedness, and superficialities, I have an immense faith in their commonsense and their instinct for life—their so-called sixth sense. Beneath their superficiality, they live a deeper life and are closer to this business of living than men, and I respect them for it.

Lin also recounts three conversations which he apparently had with women, depicting them to be ignorant in political and cultural matters—but in an 'irresistible' way.

8 December

Fig.5 A Capstan cigarette advertisement cashing in on the festive season, 29 December

Was Lin Yutang a misogynist? A woman contributor known as 'Cassandra' certainly seems to think so. Since October this year she has edited 'Cassandra's Column'; next year it is renamed 'a foreigner's viewpoint' and continues until Cassandra leaves The China Critic in July 1933.

In her essay 'Men are So Wonderful' Cassanda denounces Lin's essay of the previous week, particularly his description of women as 'superficial'. She argues that if women do behave in the asinine manner that Lin suggested, they do it to pander to perverse male vanity, which men are too stubborn to recognise:

I suggest that the next time Lin Yutang amuses himself by talking with women, he try out the game of seeing whether or not most women prefer to talk like morons, act like fools, and reason like children, or whether they do it because they have so little respect for men that they truly believe that only such undignified methods can possibly bear fruit.

15 December

Most probably as a result of the lively exchange betweenLin Yutang and 'Cassandra', The China Critic publishes three essays on women's issues. The Editorial 'China's Womankind at a Crossroad' introduces the two special articles of the issue, and describes the editorial position of The China Critic as being one which '[does] not believe in sex equality, but we know for sure that the sexes have complementary parts to play, each therefore important and indispensable in its own way'—similar to Havelock Ellis' use of the word 'equivalent' to describe the sexes in his book Men and Women.

In 'Feminist Movement in China', Shao-wei Chang 張少微 proposes that Chinese feminism was born out of revolutionary fervor at the time of the overthrow of the Qing dynasty in 1911. She draws particular attention to the actions of a nurse, Mary Chang, and provides a long and detailed account of Chinese feminism from then until the present, mentioning a number of important events and notable women in this history.

Another contributor named H. Petherton in 'China And the New Woman' discusses the political proclivities of modern Chinese feminists.

1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1945

|