|

||||||||||

|

FEATURESAn Association to Save China, the Baohuang Hui 保皇會 A Documentary AccountJane Leung Larson

I am grateful to Raymond Lum of the Harvard-Yenching Library for introducing me to Jane Leung Larson, and for Jane's kind support for this Xinhai Revolution issue of China Heritage Quarterly. The following material has previously appeared on the Baohuang Hui website. It is reproduced here with permission (and minor, editorial revisions).—The Editor How Baohuang Hui Reformers Nurtured Chinese Citizenship and Set China on the Course to RevolutionChinese reformers in the late Qing failed in their mission to recast China as a constitutional monarchy and save it from what they feared would be a disastrous revolution. Yet, some historians consider the 1911 Revolution's rupture with the past as unattainable without the reformers' more than decade-long movement to inculcate the values and aspirations of citizenship, nation, and constitutionalism in the Chinese people. The reform movement largely operated outside of China because of the prohibition against political associations and because Chinese living overseas measured their homeland's backward government against their experiences abroad and sought change. We can explore the overseas reform movement and its contributions to the 1911 Revolution by a tour of ten documents from a little-known but once powerful global organization, the Baohuang Hui (the official English name of this group is 'Chinese Empire Reform Association'). Through these documents, dated from 1899 to 1906, we can trace the organization's history and engage with the dreams and fears that animated its large membership. These documents were displayed in Hong Kong Museum of History's exhibition, Centenary of China's 1911 Revolution, organized with the collaboration of the Hubei Provincial Museum, 2 March-16 May 2011.

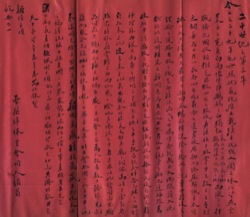

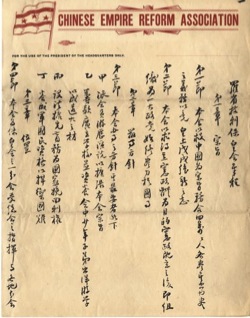

Baohuanghui Scholarship is a collaborative online forum for documenting and presenting Baohuang Hui research from around the world. It includes occasional postings with news of events, archival findings, research questions, and new leads new materials. Perhaps most useful to researchers are the frequently updated lists of archives, scholars working in the field, and bibliographic sources, as well as a slowly forming organizational map, organized by continent, of the Baohuanghui's chapters, schools, businesses, newspapers, women's auxiliaries, and other institutional appendages (formatted as Google Docs, requiring a gmail address to access). The blog was created in 2009 to overcome some of the challenges of studying such a dispersed organization, with approximately 150 chapters in Asia, the Americas, Australia, and possibly Africa, as well as newspapers, businesses, schools, and other activities inside China. Logistics alone make study of the Baohuanghui as a global organization difficult. Those who have studied local chapters of the Baohuanghui often neglect the interrelated activities of the organization in China or the frequent transnational business that involved members in far-flung places. Furthermore, limited interchange between those studying overseas Chinese history and those studying Chinese history has meant that scholarly knowledge about the organization has been compartmentalized. For example, most scholars of Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao have touched only incidentally on the Baohuanghui, although Kang and Liang were its top leaders and spent much of their lives involved in its activities. So it is not surprising how little scholarship has been devoted to the organization's history worldwide or to its significance for Chinese political development. There have been only a handful of books devoted to the organization, none to its development worldwide, and some of the most significant work remains unpublished. This blog seeks to stimulate more scholars to delve into the rich materials that are available as well as help uncover those that have survived but remain un-examined by researchers. Access to these documentary resources may encourage collaborative research as well as viewing the Baohuanghui in its broader context, not only in terms of its impact on modern Chinese history but also its innovations as a Chinese voluntary organization and its pioneering methods of propaganda and communication, for example. Unfortunately, the blogspot.com domain has been blocked in China for several years, greatly decreasing access for PRC scholars.—Jane Leung Larson.  A drifting stranger from 20,000 li away [10,000 kilometers, 6,250 miles]; Long white sideburns of forty years' time [Kang was born 1858]; Turning to look at the Milky Way and enjoying the bright moonlight; Most rare on Wen Dao [Coal Island] to chat with fellow villagers; Ashamed to shock the neighbors with the troubles and disasters of our party; Ashamed of having accomplished nothing for our fellow countrymen; Afraid this may be a separation forever from my native place... Adrift from China near the beginning of his fifteen year exile, the Cantonese reformer and utopian philosopher Kang Youwei found himself on Coal Island in distant British Columbia celebrating the twenty-eighth birthday of the imprisoned Guangxu Emperor and mourning the death of Kang's six compatriots who had been beheaded upon the failure of the Emperor's Hundred Days of Reform a year earlier. Kang had fled his homeland with a price on his head for his role in the abortive 1898 Hundred Days of Reform, after this ambitious program was brought to an abrupt halt by Empress Dowager Cixi and her conservative supporters. The Guangxu Emperor had rapidly unveiled the Hundred Days reforms throughout the summer of 1898 to initiate a sweeping agenda of political, economic and social change largely derived from memorials Kang and his associates had written to the throne. Their ultimate goal was to transform the government from being autocracy to become a constitutional monarchy. Apart from the Emperor, Kang was the person most closely identified with the Hundred Days. After having receiving a message of distress from the Emperor, he fled for his life just before the Emperor himself was put under house arrest. In exile, Kang began to approach foreign governments seeking their help to restore the Emperor to the throne. Having failed in this quest in Japan, Kang set out for North America and Europe, arriving in Canada in April 1899. Because Kang feared assassination by imperial agents, he spent much of his time on the tiny Coal Island near Victoria, BC, contemplating the failure of the Hundred Days, writing poems and learning how to fish. Kang's first public talk at the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in Victoria, BC, was a defining moment for him. The audience applauded fervently when he called out, 'Do you want China to strengthen itself? If so, please clap your hands! Do you hope for the restoration of the Guangxu Emperor? If so, please clap your hands!' This was the first time that Kang had attempted to communicate directly with ordinary Chinese, rather than with the educated elite he met in Japan or China. Yet he continued to seek intervention from foreign governments to remove the Empress Dowager and went ahead with his plan to travel to England. There, Kang came close but failed to persuade the British government to make any military or political move and finally abandoned his hopes of help from on high to restore reform in China. He returned to Canada. When this poem was written, the Baohuang Hui (Protect the Emperor Society) was two months old, having been founded in Victoria on 20 July at the Chinese Theater after a flurry of discussion between Kang and a group of local merchants. Kang had initially suggested the name Baoguo Hui 保國會 (Protect the Nation Society), which had been used for a soon-banned organization that Kang had initiated in China in 1898 but, when a local leader suggested Baohuang Hui, Kang realized that linking the organization to the person of the admired Emperor was good strategy. What in September 1899 was little more than a shell of an organization had, eight months later, become a movement with enough committed members that it could mount a telegraph campaign from abroad, which contributed to forcing the Empress Dowager to withdraw her plan to replace the Emperor. Liang Qichao made Yokohama the base of the Baohuang Hui and traveled to Japan, Australia, SE Asia and Hawaii to form chapters. Kang sent other disciples to North America to expand the organization in Canada and all over the US from small towns in Oregon and Montana to San Francisco, New York, Boston and Los Angeles.  2. A letter from Kang Youwei in Penang to Tom Leung, 5 July 1901 What kind of work do we do now? It must be kept secret. If there is a leak, some people involved might be killed. Commissioners [Qing officials] have been secretly sent to Hong Kong and Macau to investigate us. Only a few comrades know what we are doing. But our failures are still due to leaks. As a result, large amounts of money have been squandered and many good and useful people have lost their lives. The Hankou Incident is a good example. Ever since fall and winter, everything that we planned to do has been known [in advance] by local officials; they in turn immediately enforced martial law and arrested our people.... Here, Kang is writing to Tom Leung, who founded the Los Angeles chapter of Baohuang Hui, and was the sole student of Kang's in the United States. As a youth, Tom had resisted the conservative impulses of his family who wanted him to pursue a classical education and joined Liang Qichao at Kang's Guangzhou academy, Wanmu Caotang 萬木草堂, the Thatched Hut among Ten Thousand Trees, which taught Western political theory, science, geography as well as a new kind of Confucian ethics. Kang's students would form the backbone of the Baohuang Hui, but only Tom Leung would move to the United States. He arrived in the summer of 1899 to assist his successful herbalist cousin in Los Angeles and would eventually open his own prosperous business as an herbalist. But his heart was with the Baohuang Hui, and, from the time of his arrival in the US until a serious dispute with Kang fractured their relationship in 1909, Tom was in constant contact with Baohuang Hui members from all over the world. He saved this correspondence and, fifty years after his death in 1931, the letters were re-discovered and given to UCLA. This letter recounts the failure of the Baohuang Hui's boldest military venture, which came as close as any of the reformers' actions, before or after, to armed insurrection. Qin Wang [raising righteous troops to save the emperor] was Kang's and the Baohuang Hui's attempt to mount a coordinated military action during the chaos of the Boxer Uprising in the summer of 1900 and restore the Emperor to his throne. Armies of insurgents in four provinces were to rise up in unison and spread throughout China. Perhaps unknown to Kang and Liang, some of their commanders had agreed to coordinate their risings with Sun Yat-sen, who was planning actions in Guangdong. In preparation, the Baohuang Hui solicited funds from the rice merchant Qiu Shuyuan in Singapore and collected smaller donations from members in Canada, Hawaii, Japan and the US, smuggled arms into China through a sham hardware store set up in Hong Kong as cover, made alliances with more experienced fighting tongs including the huge Independence Army, and recruited foreign military advisors like Homer Lea. Lea was an American military genius with no military experience, who would not only impress Kang but later Sun Yat-sen. Feverish arguments among the commanders over where to begin the uprising, with Kang attempting to coordinate the strategy from Singapore, created confusion. In the end, the uprising failed because of poor communications among the commanders and delayed funding from overseas, which caused the scheduled attacks to be postponed. However, the Independence Army commander in Datong attacked prematurely, and the Baohuang Hui plot was discovered by Governor-General Zhang Zhidong. The Baohuang Hui lost their top military commander, Tang Caichang, who was executed, and they never again attempted an uprising. Sun's attempt from the south later in the year also failed, but he continued to stage revolts throughout the decade. The immediate result of Qin Wang was the increased caution and secrecy forced upon Kang and other Qin Wang collaborators by the threat of assassination or arrest. In Macau, Kang had to shut down Baohuang Hui activities and the influential newspaper, Zhixin Bao, 'to avoid suspicion by Qing commissioners. If we cannot establish ourselves in such a small place, how can we possibly establish a nation?' In this letter, Kang denounces the false hopes of Homer Lea and Yung Wing, whom he feels have no understanding of the weakness of the reform movement or the backwardness of China. Yung Wing was indeed a dual citizen of both the US and China, having gone to high school in the US, become the first Chinese graduate of an American college in 1854, and married an American woman, but he was also a supporter and friend of Kang's and almost lost his life in Qin Wang. Kang later relied on Yung to help his daughter, Tongbi, when she came to Hartford for high school studies in 1903. When Kang himself came to the US, he was in touch with both Lea and Yung, so his enmity passed. Both Lea and Yung, however, would eventually abandon Kang for Sun's revolutionary cause.  3. Letter from Baohuang Hui leaders Li Fuji and Dong Qiantai in Victoria, BC, to Tom Leung, 26 August 1901

Li Fuji and Dong Qiantai were two of Kang's first strong allies in Canada. At Kang's urging, Li became the Victoria branch president. This letter's plain-spoken, emotional language, awkward phrasing, and many mistakenly written characters reveal Li's and Dong's lack of education. Like many of his Baohuang Hui compatriots in Canada, Li ran a legitimate opium business, the lucrative drug still legal in Canada. Kang's trust in Li and Dong illustrates how far he had come from his days of organizing in elite circles, such as 1895 when he rallied more than 1,000 fellow examination candidates in Beijing to sign a petition calling for reforms. Particularly in the Americas, where most Chinese immigrants were laborers or small-time merchants, Kang had to tailor his message to a new, less sophisticated but more easily politicized, constituency. Li and Dong recognize the opportunity to awaken overseas Chinese to the reform cause because they had a different perspective on China, but acknowledge how even they must be politicized: People inside China generally have a very narrow view [look at the sky from the bottom of a well] and are still sound asleep. This is understandable. But even those who are abroad, who have witnessed harsh treatment and many other abuses toward Chinese by foreigners, are still unconcerned about their emperor and their country, and even worse, are betraying their emperor. No wonder the country is in imminent danger. Canadian Baohuang Hui members in particular would come through for Kang, with Ye En, the top Baohuang Hui leader in Canada being given responsibility for establishing the Commercial Corporation in Hong Kong, and others, including letter-writer Dong Qiantai, sent by Kang to Hong Kong to run Baohuang Hui businesses. Kang, Liang and the Baohuang Hui are often credited with being the first to widely propagate the passions and ideals of nationalism to Chinese citizens, especially to those overseas. In the late Qing, the concept of the nation was unfamiliar to most Chinese, who identified more with their hometown than their homeland, and referred to their country as the Great Qing Empire rather than as China. Nationalism, including that espoused through the Baohuang Hui, tended to stem from anti-foreign, or even anti-Manchu, sentiments, but Kang and Liang exploited these galvanizing elements of nationalism to introduce ideas of constitutionalism, citizenship, and modernization, both of self and nation. Above all they espoused the view that caring for the country should be equivalent to caring for one's family. The shock of the failure of Qin Wang is palpable here. In fact, Li Fuji had donated and raised funds for Qin Wang, and he shows his frustration with his fellow citizens for not being more generous: 'It is a pity that many people of the yellow race would rather become the slaves of foreign countries than untie their purses to donate money to our cause… All of our military and political activities need money. It's not easy to raise funds.'  4. Printed document from the New York City chapter of the Chinese Empire Reform Association, 21 November 1902 ...Since Mr Xu Qin visited here and delivered lectures on national affairs, telling us about the extremely dangerous situation in China and the advantages of the reform, we were all awakened and concerned. Our patriotic feelings were aroused. Therefore we organized the Association here even though our strength was limited. Following those who have preceded us [the already established chapters], we wish to wake up those who are still ignorant and help save the deteriorating national situation and carry out our responsibilities as Chinese citizens. If you do not mind, please send us the address of your branch and photos of your board members. We will hang them in our hall so that we can pay our respects... Here is the Baohuang Hui network in action. Xu Qin, who had studied under Kang in Guangzhou, was one of several Baohuang Hui activists Kang dispatched throughout the world to organize local chapters and revive those that were lagging. He arrived in San Francisco in August 1901 and subsequently traveled to many cities in the Americas, including Canada, Mexico and Cuba. New York City was already a major population center for Chinese Americans, and this greeting letter on letterhead boasts an important Chinatown address, where the chapter had already established a meeting hall. Xu approached local Chinese leaders in his organizational drive, and the New York chapter was headed by Joseph Singleton. Singleton (Zhao Wansheng) was a Sunday School teacher and banker, who consciously integrated the Baohuang Hui into mainstream society. In the name of the Association, he later helped organize two newsworthy fund-raisers in 1903 and 1905 raising over $1,200 for the Jewish victims of a pogrom in Russia. The vivid effect of 40 Chinese enacting 'King David' for an audience of whites and Chinese was reported in the New York Times. Sharing the Lower East Side neighborhood with Jews, the Chinese both admired the Jews for their success in American business and cultural life and empathized with their status as the victims of discrimination. [See also: 'The Night New York's Chinese Went Out for Jews', by Scott Seligman in this issue—Ed.]. New York quickly became an important chapter in the Northeast, with a newspaper, Zhongguo Weixin Bao; a bank, Huayi Yinhang; a women's auxiliary; and a branch of the Baohuang Hui's military training school. Kang chose New York City as the site of two Baohuang Hui congresses in 1905 and 1907, which brought leaders from as far away as Hong Kong, Macau, and even Australia. Kang led these meetings and introduced new organizational documents to govern the Baohuang Hui and its 1907 successor, the Constitutional Association (Xianzhenghui 憲政會).  5. New Year Greeting Letter from Sydney Baohuang Hui to comrades in other cities, 1903 The fortunes of our country are being controlled by a few traitors. They confuse truth and falsehood. They borrow the name of the crafty Empress Dowager to oppress the Han nationality. That is why the poisonous autocratic system has been able to last for thousands of years. That is why the 400 million descendants of the Yellow Emperor have lived under constraints and humiliation all their lives [unable to express their feelings or take the initiative]. People have lived in an environment in which they feel like the enemy is in every bush and tree, in a state of extreme fear.... This passionate letter from one of the eleven far-flung chapters in Australia was written to encourage other chapters upon the New Year. Its anti-Manchu rhetoric stands out from other reform propaganda of the time, perhaps because Australia was in foment due to the White Australia Policy, which heightened race consciousness among Chinese there. Also, by 1903, there were many Australian Chinese sympathetic to the anti-Manchu revolutionary cause, although Sydney remained staunchly in the reform camp. Two years earlier, Liang Qichao had spent six months in Australia, just as the Immigration Restriction Act was being debated and then enacted. The Australian Baohuang Hui chapters attempted to unite Chinese in protest against this and other anti-Chinese legislation, and much of Liang's public speaking during his trip focused on the topic of equality. [See also: Liang Qichao in Australia: a sojourn of no significance?, by Gloria Davies in this issue—Ed.] No doubt Liang had also propagated the social Darwinist view adopted by many Chinese modernists and expressed in this letter—that China could never compete in the modern world under rule by a corrupt, incompetent Manchu court. The only solution was for citizens to stand up and work for change. The need for Chinese to improve themselves, modernize their culture, and be worthy of respect by Westerners was also part of his vision of the New Citizen (xinmin 新民).  6. Handwritten charter drafted by Liang Qichao for Los Angeles chapter, November 1903 Chapter 1: Objectives Section 1: This association aims to save China. The 400,000,000 Chinese people have an obligation to continue their efforts to carry on the reforms proclaimed by the Emperor in the year of Wuxu. When Liang Qichao visited the US in 1903, he was deeply disappointed by the disorganization and inability to cooperate that he observed in the Chinese American community, especially in San Francisco. After this trip, he famously rejected the idea of revolution, one which he had toyed with from 1900. In his journal of his American travels, Liang wrote that the bylaws of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association were 'by and large patterned after organizations in the West—very civilized and very detailed. But when I observe their implementation, there was not a single instance where the actions were not contrary to the provisions [of the bylaws].' However, it must be noted, Liang had observed firsthand a competitive election of Baohuang Hui leaders in Canada complete with vigorous campaigning and described it as an historic event in the formation of Chinese political parties. Both observations might have led Liang to take great pains in composing the following document, the charter for the Los Angeles Baohuang Hui. He explained: 'Probably I put in too many details in the section on meeting procedures. This is because Chinese people never had any rules for holding a meeting, and therefore a meeting often ends up with no decision or resolutions. This charter takes the meeting rules of Western meetings of all kinds as a model, and we Chinese should learn from them.' This charter makes clear that Baohuang Hui was seen as the vanguard of a Chinese political party that would participate in a future constitutional government, and until that time would provide the mechanism for fighting to restore the 1898 reform program begun by the Emperor. A constitutional system was the ultimate goal, and there is no mention of protecting the Emperor. Indeed, in 1906, as the Qing government began to implement its own constitutional reforms, Kang changed the Baohuang Hui's name to Zhonghua Diguo Xianzhenghui 中華帝國憲政會 , the China Imperial Constitutional Association (Xianzhenghui for short). In the charter, one can see how the organization was structured in anticipation of running a nation, with its guidelines promoting the development of educational, commercial and military institutions not just for the individual benefit of its members but for the nation. Membership was 'open to any patriotic Chinese... regardless of their surname, native place, or religion,' and each member was obligated to pay dues. Funds in its treasury were to 'be treated like national bonds' that would be re-paid with a share of the profits 'in the future when the reforms succeed.' Among the twelve categories of officers that the Los Angeles charter describes are two that consciously project the organization into the greater community: a Western Language Clerk to translate documents 'that concern relations with Americans' and Orators 'to make speeches to the public to advocate the principles of the association.' Liang also wrote a variety of cross-checking duties into the positions dealing with money, with an auditor to oversee the accountant, two treasurers responsible for common funds and local office funds, and monthly posting of the financial statement at the chapter office.  7. Letter from Kang Youwei to Tom Leung from Victoria, BC, Canada, 6 December 1904 I have just entered Canada and soon will be in the US. We will see each other soon. You can tell me everything about Los Angeles. When I tour places, I will definitely visit their factories, government agencies, and schools because these are very important. I would like to have a disciple or close relative accompany me so that I can entrust a lot of things to that person in the future. Do you wish to tour with me? Send me a telegram if you do. Kang was by now a veteran international traveler, but his style of intense immersion in each national culture he encountered had been set early in his exile. Even before Kang first set foot in North America on 7 April 1899, a Canadian newspaper described him after he went through the quarantine procedure aboard the ship: 'When the liner moved in from quarantine to the city, his interminable questions resumed—what was Victoria's population; its manner of municipal government; its facilities for policing and protecting against fires; its school and hospital arrangements?' Kang arrived in the US in February 1905, traveling south from British Columbia and visiting Baohuang Hui chapters along the way, and coming to a halt for two months of rest and recuperation in Los Angeles, where his student Tom Leung lived. They then embarked upon a journey back and forth across the US from May to December, visiting Montana copper mines, Yellowstone Park, Yale University, as well as the Sing Sing Penitentiary; meeting with President Theodore Roosevelt twice to discuss the Chinese Exclusion policy and the threatened anti-American boycott in China; speaking to American church groups and innumerable gatherings of Chinese; and, holding the first congress of Baohuang Hui chapters in New York City. In addition to Tom, Kang's entourage included his interpreter and the American Homer Lea, who by that time presided over a network of Baohuang Hui military schools, the Western Military Academy. Kang's daughter, Kang Tongbi, who had been studying English and attending high school in Hartford, Connecticut, since 1903 joined her father when he was on the East Coast. This letter also alerts Tom to Kang's fear of assassination, especially at the hands of revolutionaries, and requests his help in obtaining bullet-proof body and head armor made of paper and hair (Tom is told to test the products by shooting at them prior to purchase) as well as weapons. Lightweight paper and hair armor was used in ancient China, so Kang must be suggesting Tom visit San Francisco's well-supplied Chinatown to buy these.  8. Letter from Kang Youwei to unknown addressee on letterhead printed with Baohuang Hui flag and in English across the top, 'Chinese Empire Reform Association Headquarters, For the use of the president only,' February-March 1905 I have been in America for a month and have become somewhat familiar with the situation in different cities. The number of people [investors?] in the Commercial Corporation is not great [less than two or three thousand]. Although I was given solicitous hospitality, the shares they raised were very few. There are probably many factors. I think that people in these cities have no certainty of earning money in this business, and, as a result, I cannot persuade them with my empty words. Judging from the situation, I feel that handling the matters of the Commercial Corporation is like a fan in autumn [i.e., useless]. I have traveled all the way to America but have ended up empty-handed. I really feel ashamed. Both Liang in 1903 and Kang in 1905 would be challenged by the difficult task of selling stock shares in the US for the Baohuang Hui's Commercial Corporation, which had been founded in Canada in 1902. Although its broader goal was as stated in the Los Angeles charter guidelines, 'to recover our nation's economic rights', a secondary and ultimately more pressing goal was to raise funds for Baohuang Hui institutions, including schools, sending students abroad, newspapers and publishing companies. A number of strictly remunerative activities would be incorporated under this clause, from running hotels and restaurants to building streetcar lines, establishing banks, and even buying and selling real estate, many of these ventures directly involving Kang himself. Even though Kang appears greatly disappointed at the response from Chinese Americans to his solicitations, this multinational conglomerate would grow rapidly until it was hit by the worldwide financial panic of 1907 and beset with disputes, distractions, and the corrosive impact of running many businesses while trying to carry out a political mission. By 1908, Tom Leung himself would become embroiled in a business dispute with Kang, whom Tom publicly criticized in a published defense of himself against the accusations of incompetence and embezzlement that Kang, Liang and others hurled at him. Along with other business scandals that erupted around this time, Tom's open defiance of Kang damaged the reputation of the Baohuang Hui and contributed to the rapid decline of the organization after 1909 and the concomitant rise of revolutionary support among overseas Chinese in 1910 and 1911.  9. A handbill calling for protests against the U.S. ban on immigration, Rangoon, Burma chapter of Baohuang Hui, printed on red paper, early June 1905 The United States has extended the Exclusion Act in order to put an end to Chinese people's livelihood there. This is a national disgrace second to none.... Now, all the Chinese people in the US are making every effort to achieve the goal of taking back the national rights [of the Chinese people] and saving Chinese people's livelihood. Noble-minded people in Shanghai and Hong Kong and the charitable organizations in Guangdong province have all responded enthusiastically. They worked together in full cooperation. They held meetings to discuss protest and defense measures. They communicated with each other through letters and telegrams to encourage one another to do a citizen's duty.... This remarkable document shows the reach and collective power of the Baohuang Hui to inspire nationalism and political action. We know little about the Rangoon chapter, but Kang Youwei visited Burma, Java, Vietnam and Thailand in 1903, all of which boasted Baohuang Hui chapters. The handbill reprints several documents that obviously had reached Burma (by telegram?) within a month since they most likely were produced in May 1905—a letter from Kang Youwei who was in Los Angeles at the time; telegrams from Kang and activists in Shanghai and Hong Kong; and a lyrical poem vividly depicting the humiliation suffered by Chinese under the Exclusion Act. Kang Youwei in the United States was hearing the distress of local Chinese about talk of the imminent renewal of a US-China treaty to further restrict Chinese immigration. He was moved to send an urgent telegram about the treaty to alert Baohuang Hui leaders, among them Liang Qichao in Yokohama. Liang telegraphed his compatriots in Shanghai and Hong Kong and promoted the idea of an anti-American boycott to protest the Exclusion Act, a strategy that had been laid out in a widely reprinted editorial written in 1903 by a Honolulu-based Baohuang Hui editor, Chen Yikan. To follow up, editors of the Baohuang Hui newspaper, Shi Bao, in Shanghai met secretly with powerful Shanghai merchants and officials. A few days later, on 10 May, the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce announced a nationwide boycott of American goods in China. Shi Bao became a mouthpiece for the boycott, and later in June, Kang would meet with President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington, DC, to discuss the reasons for the boycott. The 1905-1906 anti-American boycott became China's first mass movement, with overseas Chinese contributing funds and fanning the fires of the boycott with their tales of discrimination and mortification. The suffering of Chinese immigrants in the US was linked to China's plight as a nation too weak and backward to protect its emigrants from discrimination abroad. 'Boycott nationalism' shared much in common with the values that the Baohuang Hui reformers were promoting—populism, the identification of the nation with the family, citizen rights and responsibilities, solidarity and unified action, non-violence, promotion of public over private interests, and progressivism. For the reformers, the boycott was seen as an opportunity for Chinese to practice citizenship and overcome their traditional passivity, factionalism and selfishness by uniting in protest. In June 1905, Liang Qichao wrote of the boycott: 'In the last month, everyone in Shanghai has been thinking about and talking about the Exclusion Act. From millionaires to poor workers, millions of people are of one mind, and we must not stop until we win back our rights. Oh! We have been working on these matters for many years, but have never seen more success than this time.'  10. Poem by Kang Youwei written for Tom Leung, March/April 1906 The house was rented for two months near West Lake. Thousands of blooming flowers in the lovely spring. The setting sun shone over my house like golden rays. At night, it was very comfortable with electric lights shining like the bright moon. I would lie down on the grass whenever I got tired, Take a little rest and open a book to read. Passing bridges and jogging among trees, watching waves on the water's surface, I returned home after boating on West Lake, then asked for cooked fish. The beautiful lake and the old house should be just as nice as they were a year ago, When will the sounds of my footsteps be heard in the corridors again? I still remember the nights with a beautiful moon and blooming flowers. Everyday I walked with my stick to watch the moon on the lake. Kang wrote several poems for Tom Leung recalling his restful days during his long stay in a small house in Westlake Park in Los Angeles enjoying Chinese food supplied by Tom Leung's cook. Tom would visit Kang frequently, and the student and teacher would talk late into the night about China and their dreams for reforms. When this poem was written in 1906, Kang was most likely in Mexico, where there were at least nine Baohuang Hui chapters. It was during this trip to Mexico, lasting about five months, that Kang became fatefully enthralled with the business side of the Baohuang Hui, 'stir-frying land' with much success and using the funds to invest in a Baohuang Hui bank and other ventures, including a streetcar line, both in Torreón. Kang would never return to Los Angeles, but he did see Tom Leung in 1907 at the second Baohuang Hui (now named Xianzhenghui) congress in New York City. Their dramatic rift in 1908-9 over a Baohuang Hui business that Tom Leung managed foreshadowed the organization's decline overseas. ConclusionIn a sense, the work of the Baohuang Hui had been completed. The last significant political campaign undertaken by Kang, Liang and the Xianzhenghui was to engage directly in the national petition movement calling for the Qing court to convene a parliament and draft a constitution. This movement involved reformers of all stripes, including officials in the Qing government, but most were provincial elites, and almost all had read Baohuang Hui newspapers published in Japan or Shanghai and had come to champion nationalism, economic rights, constitutionalism and representative government, as publicized by the Baohuang Hui. Many would join the first provincial assemblies in 1909. From 1908-11 Kang and Liang were predominantly provocateurs, pushing more moderate reformers to demand more of the Qing, whose disappointing attempts at constitutional reform betrayed their resistance to giving up political power. Kang wrote a long petition demanding fundamental changes in the governmental system that was endorsed by the nearly two-hundred overseas chapters of Xianzhenghui and that claimed to represent several hundred thousand overseas Chinese. Liang established a kind of preliminary political party inside China, with chapters in each province, the Political Information Institute. In short order, the Qing denounced Kang's petition as absurd and banned the Political Information Institute. But the constitutional petitioners kept gathering force, ever more insistent in their demands to take part in political decision-making, spurred on by the actual exercise of political power in the newly established provincial assemblies. The tide soon turned to revolution, led not by revolutionaries but by energized and frustrated provincial assemblymen who could no longer wait to exercise their sovereignty and were instead transformed into empire-breakers. It was an end that Kang and Liang did not seek, but one that they as much as Sun Yat-sen had unwittingly set into motion. Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

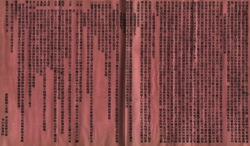

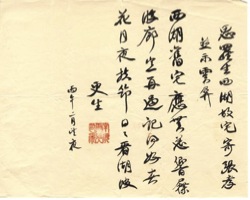

|