|

||||||||||

|

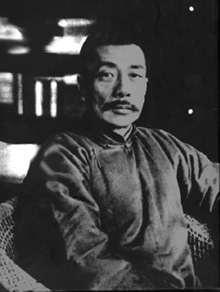

FEATURESThe Shanghai HazeGloria Davies Monash University Clayton, Victoria[1] Fig.1 Lu Xun in Shanghai In March 1928, China’s best known modern writer, Lu Xun 鲁迅 (1881-1936), remarked of the flourishing publishing scene in Shanghai that it seemed to be enveloped in an intellectual ‘haziness’ or ‘vagueness’ (menglong 朦胧) which was pouring forth from a ‘spate of new periodicals’ that had appeared earlier that year. Of the contributors to these periodicals, he wrote: ‘They seem to have exhausted themselves by thinking up great and lofty topics but with no thought for the deadly dull content that follows.’[2] ‘Haziness’, for Lu Xun, captured the intellectual ambience of Shanghai in early 1928. ‘Haziness’ was also his way of drawing attention to the political complexity of the revolutionary clamour generated in the late 1920s. As he wrote in an essay of December 1927: ‘Naturally, to revolt against the status quo is still mandatory, but it has become inadvisable to be too revolutionary. To be too revolutionary is to risk being seen as an extremist. To be seen as an extremist will lead to the suspicion that one is Communist and that will, in turn, lead one to be identified as “anti-revolutionary”.’[3] To gain further insight into Lu Xun’s remarks we need to dwell a little on and around the previous year 1927 which began, at least, with great promise for China’s Communists. In the mid-1920s, the fledgling Chinese Communist Party had demonstrated a formidable capacity for mass mobilization. By early 1927, it had led successive workers’ strikes and street protests that were highly effective in assisting the Northern Expedition (Beifa zhanzheng 北伐战争), the war effort against China’s feuding and divisive warlord regimes. The Expedition itself, launched in July 1926 with substantial Soviet financial and military aid and under the direction of Chiang Kai-shek, was prosecuted under the promising but short-lived auspices of a ‘united front’ of the Nationalist Party (Guomindang 国民党) and the Chinese Communist Party (Gongchandang 共产党). Its guiding aim of national reunification under a Nationalist government, in which the Communists would play a leading role, had attracted widespread support among China’s progressive educated elite. Lu Xun, like many other intellectuals of the emerging Chinese Left, had been much heartened by the rise of worker organizations and peasant associations in rural and urban China during this period. Committed Marxists waxed lyrical about the dawn of a proletarian era; indeed, revolutionary rhetoric became so infectious that, as one contemporary observer observed, even the ‘big bosses of industry and trade’ were chanting ‘Long Live the World Revolution!’[4] By January 1927, the total number of members enrolled in Hunan’s peasant associations—the heartland of the country’s organized peasantry—had swelled to over two million.[5] But these halcyon days of political unification were to come to an abrupt and brutal end: the very success of this Communist recruitment carried within it the warrant for its necessary eradication. As early as March 1926, Chiang Kai-shek became convinced that the influence of the Left, in a national war conducted under the Soviet Union’s aegis, could only result in Communist dominance and therefore the ultimate demise of his own Nationalist Right. In desperate need of aid to prosecute the cause of the Northern Expedition from the same Soviet Union, however, Chiang had quietly bided his time waiting for the most opportune moment to deal with the looming spectre of Communist dominance.[6] For Chiang, the fact that the Chinese Communists were winning the hearts and minds of so many so quickly was a foreboding omen of the enormous threat they posed if unchecked. Hence, on 12 April 1927, Chiang launched a sudden surprise assault on Communist strongholds in Shanghai, his troops killing hundreds of Communist activists, union leaders and workers on that one day. The bloody eradication of Communists continued into the next and further months until it had systematically etched its way across the wintering landscape of the country. As a consequence, its leadership stunned into utter disarray, the Communist Party, along with its intraparty logistical networks collapsed briefly. The briefest glance at the party registry would make this clear. In April 1927, there were some 60,000 or so registered Party members but, by year’s end, the number had plummeted to under10,000.[7] As Chiang’s sudden, unpresaged anti-Communist witch-hunt widened in the remaining grisly months of 1927, Shanghai became something of a Mecca for intellectuals of all shades. Members of the professional classes fled through the war-torn cities of the north and south in their thousands, heading for the relative safety of China’s largest treaty port. For the Left, Shanghai’s foreign concessions also offered some degree of protection from the ubiquitous Nationalist secret police. When Chiang assumed power as the nation’s president in October 1928, the seat of political power shifted from Peking to Nanking. This sudden shift of the geo-political centre of the Chinese republic inaugurated the era known as ‘the Nanking Decade’ (1927-1937) during which the Nationalists ruled from their new southern capital. Accordingly, by 1928, Shanghai had displaced Peking as the country’s intellectual centre, mirroring the shift of political power to Nanking. The northern capital (Beijing) was demoted to an ordinary city with a change of name. It was henceforth to be known as Beiping (‘the pacified north’): a name it would retain until 1949 when the city was reinstated as Beijing, capital of the newly established Communist People’s Republic. In 1928, as the daily swell of students, teachers, writers, editors and journalists mixed with an influx of merchants and members of the professional classes, intellectual life flourished in Shanghai. Lu Xun explained why he had spoken of the city’s haze-beclouded publishing scene: To my mind, the source of this haziness… remains those bureaucrats and warlords loved by some while loathed by others. Those who are or want to be entangled [guage 瓜葛] with them often pen jolly sentiments to demonstrate to everyone how amiable they are. But being far-sighted too, they have fearful dreams of the hammer and sickle and dare not flatter their present masters too openly. Thus, they are a bit hazy in this regard. As for those who are no longer entangled with them, or who have never been mixed up with them—those who want to advance and join the masses—they should be able to speak without fear. Yet, although they seem so imposing in print and present themselves as heroes, few are foolish enough to forget who actually wields the commander’s sword. Thus, a bit of haziness comes across [in their writing] as well. As a consequence, those who want to be hazy end up revealing some of their true colours while those who want to show their true colours cannot avoid being a bit hazy. All of this is happening in the same place at the same time.[8] Here, Lu Xun includes Chiang Kai-shek among the ‘warlords’. He bemoans the political complexity of the post-revolutionary era in which ambitious intellectuals were busy making plans in wily attempts to ensure they remained within the unsteady orbit of contemporary political power. Using the mostly derogatory term guage (which also means mixed up, embroiled, caught up), he implies that such people, despite carefully hedging their bets between the Right and the Left, would inevitably be dragged down by the bad company they had kept. Above all, Lu Xun’s discussion of ‘haziness’ highlights the prevalence of the kind of self-censorship common under any authoritarian regime. Throughout 1928, the writer launched one scathing attack after another on the revolutionary commerce that Shanghai publishing encouraged. For instance, he wrote in April 1928 that it was best to treat the revolutionary literature of Shanghai as a mere ‘signboard’ under which ‘writers talked up the essays of their mates while never daring to look directly at the present brutality and darkness.’[9] The now besieged Communist Party, operating via an extensive underground network based in Shanghai, was naturally keen to enlist the support of the city’s intellectual luminaries. But while Lu Xun willingly lent his prestige to the Communist cause, he was ever suspicious of Marxist theorists keen to style themselves as members of a vanguard. In March 1928, he mused that if they succeed in becoming ‘so many Vladimir Illyiches and really “won over the masses”,’ his writings would most certainly end up being banned.[10] He could not foresee that a very different fate lay in store for him. It was the (often) plain-speaking Mao Zedong, rather than the urbane sophisticates given to quoting Marx and jeering at Lu Xun’s ‘backwardness’, who would become China’s very own Helmsman.  Fig.2 Artist unknown, 'Carry forward the revolutionary spirit of Lu Xun' (继承和发扬鲁迅的革命精神 Jicheng he fayang Lu Xunde geming jingshen), Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, ca.1973. Source: IISH Stefan R. Landsberger Collection. In 1937, one year after Lu Xun’s death, Mao canonised the writer as a virtual revolutionary saint. Thereafter, Lu Xun became an integral part of the Chinese Communist dogma with his texts being regularly mined for axioms and aphorisms to lend moral authority to the party’s various Diktat. In this connection, much of Lu Xun’s critical oeuvre, including his notion of ‘haziness’, has been used to attack those who dissent from the official orthodoxy of the moment. Nonetheless, the complex nuance Lu Xun imparted to ‘haziness’ in 1928 ensures that it will always exceed such ideological constraints. Since the 1990s, a radical disconnect has developed between regnant party theory (which justifies its unelected rule by employing a Marxist-Leninist vocabulary) and the everyday operations of the party-state (now fully focussed on economic growth and market calculations of risks and returns). Here, we should also note that Lu Xun chose carefully the term guage, precisely for its hint of gangsterism, for which Republican-era Shanghai was infamous. Indeed, it was with the aid of Du Yuesheng 杜月笙, leader of the Green Gang (Qingbang 青帮) and Shanghai’s most notorious gangster, that Chiang Kai-shek launched his coup against the Communists on 12 April 1927. In August 2009, the launch of a massive crackdown on organized crime in the south-western metropolis of Chongqing in Sichuan province revealed an intricate web of relationships between gang leaders and party officials. While media coverage on that occasion was focused on Chongqing, the issue of widespread collusion between criminals and officials in Shanghai and other cities was nonetheless widely discussed on the Chinese Internet. In October 2009, Southern Metropolis Weekly (Nandu Zhoukan 南都周刊) drew particular attention to revelations of an extensive extortion racket run by local law enforcement agencies in Shanghai.[11] Indeed, censorship (both voluntary and coerced) remains to this day a haze that envelops Shanghai’s nonetheless thriving intellectual publishing scene. It can also be discerned in the embargo on a wide range of topics deemed too sensitive for media coverage, including the abuse of official power, the harassment (and in some cases imprisonment) of human rights defence lawyers and activists in Shanghai and elsewhere, not to mention the disgruntled murmurings of local residents forcibly relocated from their homes on the Shanghai 2010 Expo site and the detention of the more voluble among them whose complaints have attracted public attention.[12] Thus eighty-two years after Lu Xun’s penetrating gaze into Shanghai’s haze, people are again flocking in droves to China’s most famous costal city. The beckoning glitter of the Shanghai Expo 2010 is supposed to lure at least seventy million visitors worldwide. It is a metropolis that is a far cry from the Shanghai that held a glimmer of hope for a future, one that sought to embrace the country’s oppressed labouring masses. What drew Lu Xun and other intellectual refugees to the swelling city was the possibility they saw to establish a new and intellectually free life in what was otherwise a time of violence and terror. To that end they published vigorous polemics in their newly-founded periodicals, each and all worrying about how their fragile nation could progress towards a better future. In 2010, we should pause to recall the Chinese Communist Party’s time in extremis in 1928. Its operations then, as an underground organisation rallying support for its vision of a future, proletarian China is worlds away from its present-day triumphs. For the ambitious individuals keen to foster advantageous connections with the party-state today, a display of revolutionary rectitude is no longer required. Indeed, the party is anxious to show that it is addressing the catastrophic problems of official corruption. However, ‘haziness’ is now also endemic to the state-guided media whose fluctuations between candour and coyness (on this and other pressing issues) reflect the anxiety of an unelected government unsure as to how best to manage the gulf between its particular form of political theory and the realities of state practice. While the masses are drawn again to the ‘expositions’ of Shanghai, it is not out of any hope for an equitable proletarian future, but rather out of an epochal desire to touch a future now arrived. For the very idea of the Shanghai Expo embodies a faith in sheer modernity, manifest in the Expo’s international shrines to a future made concrete and on display. It is a future of heedless production and tireless consumption. Notes:[1] This essay is based in part on material from my forthcoming book Guns and Words: Lu Xun, Revolutionary Literature, Shanghai. Grateful thanks are owed to M.E. Davies for valuable comments and suggestions, and to the editor of China Heritage Quarterly. [2] Lu Xun, ‘The Haziness of “Drunken Eyes” (‘Zui yan’ zhongde menglong) in The Collected Works of Lu Xun (Lu Xun Quanji), vol.4, Beijing: Renmin Wenxue Chubanshe, 1991, p.61 (Hereafter referred to as LXQJ). My translation is based on that of Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, which appears as ‘Befuddled Woolliness’ in Lu Xun: Selected Works, vol.3, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1980, p.15. [3] Lu Xun, Mixed impressions on the confiscation of Threads of Talk’ (Kou Si zagan), LXQJ, 3:485. [4] Chang Kuo-tao (Zhang Guotao), The Rise of the Chinese Communist Party, vol.1, Lawrence: The University Press of Kansas, 1971, p.547. [5] Harold Isaacs, The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1961, p.113. [6]An engaging account of these developments is presented in Isaacs, The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution. Isaacs was a contemporary observer who staunchly supported Trotsky’s position on the revolution in China. (After Trotsky’s death, he distanced himself from the Trotskyists). Despite Isaacs’ partisanship, his empirically rich account of Chiang Kai-shek’s growing hostility toward the Communists has largely been borne out in subsequent scholarship. [7] Denis Twitchett and John K. Fairbank, eds., The Cambridge History of China: Republican China: 1912-1949, vol.12, pt.1, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983, p.169. [8] Lu Xun, LXQJ 4:61. Some phrases have been taken from ‘Befuddled Woolliness’, Lu Xun: Selected Works, vol.3, p.16. [9] Lu Xun, ‘The Arts and Revolution’ (Wenyi yu geming) in LXQJ, 4:84. [10] Lu Xun, LXQJ, 4:66. [11] See, for instance, ‘Redressing Shanghai’s “fishing” scandal’ (Shanghai diaoyu shijian xiyuan lu), Nandu Zhoukan, 2 November 2009, posted at: http://nf.nfdaily.cn/ndzk/content/2009-11/02/content_6164079.htm. ‘Fishing’ was the term used to describe the practices of entrapment and extortion pertaining to this case. [12] On the issue of individuals detained for complaining about their forced eviction, see ‘Citizens find no redress for home lost to Shanghai Expo’, 30 April 2010, a press statement posted on the website of Human Rights in China, http://www.hrichina.org/public/contents/press?revision_id=174689&item_id=174371; on the question of additional restrictions imposed for the duration of Shanghai Expo, see ‘Shanghai Authorities Tighten Control on Petitioners ahead of Shanghai World Expo’ (Shi bo jinzhang Shanghai yankong fangmin), Radio Free Asia, 31 March 2010, at: http://www.rfa.org/cantonese/news/petitioners_shanghai-03312010122534.html |