|

||||||||||

|

FEATURESThe Universal LibraryDuncan CampbellIn his story 'The Library of Babel', Jorge Luis Borges describes a universal library: The Universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries. In the center of each gallery is a ventilation shaft, bounded by a low railing. From any hexagon one can see the floors above and below—one after another, endlessly. The arrangement of the galleries is always the same. Twenty bookshelves, five to each side, line four of the hexagon's six sides; the height of the bookshelves, floor to ceiling, is hardly greater than the height of a normal librarian. One of the hexagon's free sides opens onto a narrow sort of vestibule, which in turn opens onto another gallery, identical to the first—identical in fact to all. Later in the story, he captures something of the troubled history of book collecting: When it was announced that the Library contained all books, the first reaction was unbounded joy. All men felt themselves to possessors of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal problem, no world problem, whose eloquent solution did not exist—somewhere in some hexagon. The universe was justified; the universe suddenly became congruent with the unlimited width and breadth of humankind's hope. At that period there was much talk of The Vindications—books of apologiæ and prophecies that would vindicate for all time the actions of every person in the universe and that held wondrous arcana for men's futures. Thousands of greedy individuals abandoned their sweet native hexagons and rushed downstairs, upstairs, spurred by the vain desire to find their Vindication. These pilgrims squabbled in the narrow corridors, muttered dark imprecations, strangled one another on the divine staircases, threw deceiving volumes down ventilation shafts, were themselves hurled to their deaths by men of distant regions. Others went insane…. The Vindications do exist (I have seen two of them, which refer to persons in the future, persons not imaginary), but those who went in quest of them failed to recall that the chance of a man's finding his own Vindication, or perhaps some perfidious version of his own, can be calculated to be zero. In somewhat similar vein, the Yuan dynasty writer Yi Shizhen 伊世珍 encapsulates something of the quest that underpins much traditional Chinese book collecting in the following story:

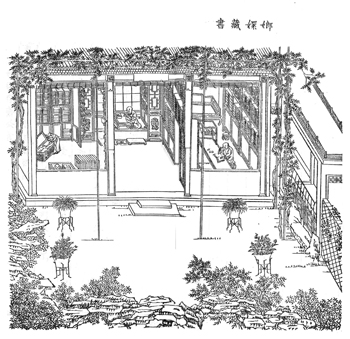

The late Ming historian and essayist Zhang Dai 張岱 (1597-?1684), whose own extensive family book collection was lost in the chaos of the Ming-Qing dynastic transition, enters, briefly and only in a dream, this projected paradise at the end of his evocation of the splendours of his youth, Tao'an's Dream Memories (Tao'an mengyi 陶庵夢憶): Taoan's dreams are as if predestined, and often in his dreams he finds himself within a stone hermitage, set amidst 'chasms inside chasms, caverns in crags'. In front of this hermitage, a torrent rages and a brook swirls, the cascading water producing snow-like foam, with fantastically shaped ancient pines growing amidst eccentric aged rocks and with famous flowers interspersed here and there. In the midst of all this he sits, in his dreams, with serving boys plying him with tea and fruit, and surrounded on all sides by shelves laden with books. Although whenever he happens to open up a volume, he finds that the text is written largely in the tadpole, bird trace or thunder script of antiquity, yet in his dreams it is as if he can understand even the most troublesome and abstruse of passages. When living in idleness with nothing to occupy his time, he finds himself dreaming of this place as the evenings gather in around him. Meditating upon it when he awakens, he resolved to seek out a marvellous site that could be made to resemble that of his dreams'. |