|

||||||||||

|

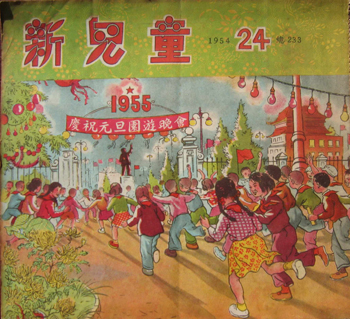

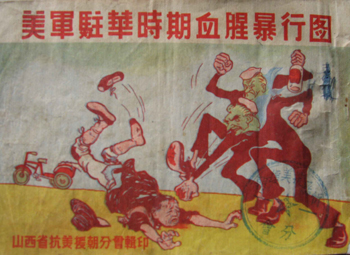

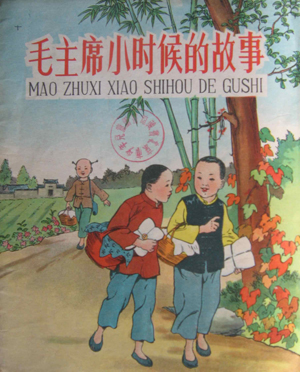

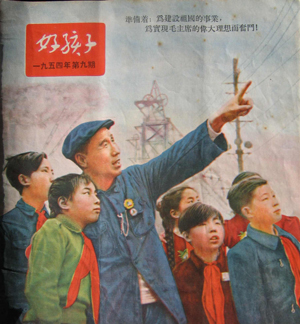

FEATURESA Bibliophile in SinDon CohnThis is a short bibliomemoir by Don J. Cohn, a writer, translator, book lover, book collector and Beijing-ophile. It offers insights into aspects of the trade of Chinese books both within and outside of the People's Republic not touched on elsewhere in this issue, or for that matter in other sources. Don studied Chinese at Oberlin College and Columbia University. He lived and worked for long periods in Beijing, Hong Kong and Taiwan. He worked as an editor at Renditions magazine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and as books editor at Far Eastern Economic Review. Since 1979, he has operated over 175 tours to China; written, translated and edited books and articles on subjects of Chinese interest; and today is active buying and selling printed matter from China and Japan. As a New York native and owner of five Pekingese dogs we expect that Don would appreciate Groucho Marx's observation, 'Outside of a dog, a book is a man's best friend. Inside of a dog, it's too dark to read.' (It's a remark that inspired the title of Rick Gekoski's Outside of a Dog: A Bibliomemoir, Peribo, 2009). The land of Sin or Sinim, mentioned in the Bible (Book of Isaiah 49:12), was thought by some to be China. All illustrations are of covers from books acquired by the author and are reproduced with his permission.—The Editor The Cotsen Connection A casual remark made to me at a lunch at the Hong Kong China Club by an American book dealer set me on the path that I am still pursuing today: buying, selling and collecting Chinese and Japanese books. In 1995, I was extremely fortunate to have been introduced to Lloyd Cotsen through a book dealer, who I met through a friend who worked at Sotheby's in Hong Kong. Lloyd Cotsen is a remarkable man: collector, philanthropist, archeologist, connoisseur of Chinese food and grape wine. He has accumulated and donated to major public institutions world-class collections of Japanese baskets, textile fragments, folk art, Noah's arks and children's books. Over the course of the past 15 years, I acquired and sold to the Cotsen Children's Library at Princeton University, a purpose-built annex of the Firestone Rare Books Library, over 50,000 textbooks, readers, picture books, periodicals, games, posters and ephemera for children from China, Japan, Korea, Manchoukuo, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam and India. Yet these Asian materials are only a small part of a spectacular collection that includes everything from cuneiform tablets and Eskimo hunting primers painted on sealskin to Nazi propaganda and early Yiddish story books, along with major collections of Beatrix Potter and children's classics from Comenius to Hans Christian Andersen, the Grimm Brothers, Lewis Carol and much beyond. Equally remarkable is the way Lloyd's life has touched mine in a number of other indirect and coincidental ways.  Lloyd Cotsen attended Columbia High School in South Orange, New Jersey, approximately eight years after my father attended the same school, in the years immediately before and after World War II, but they did not know each other at the time. And it was only after I met Lloyd Cotsen in Los Angeles and conducted our first transaction that I learned that my step-mother had traveled with him in South America and had known him for over ten years. Lloyd Cotsen made his fortune by transforming Neutrogena, the one-time California soap company started by the father of his first wife, into an international lifestyle brand, and eventually selling the company to Johnson & Johnson. His life is marked by a tragedy. In 1979, his wife, son and a son's friend were murdered in cold blood by a Belgian business competitor who broke into the Cotsen home intending to kill Lloyd, who was away on a business trip. Until that point, Lloyd Cotsen's nonprofessional interests were focused more on archeology, Japanese baskets and textiles than on his wife's collection of rare children's books. But in 1995, he made a major donation to Princeton University, where he had studied history as an undergraduate, to build the Firestone extension and stock it with an initial gift of 23,000 mostly European and American children's books. Mr Cotsen's generous and broad mandate to me for Asian children's books was straightforward and basically sociological: acquire material for young children, preferably illustrated, that shows how the child's consciousness is formed to reflect such issues as nationality, family, society, religion, authority, war, and prejudice. 'Seek out material from troubled countries in troubled times.' Little did either of us anticipate the amount, and quality, of printed matter that filled that requirement, especially from China and Japan. A New Market from Old In 1995, the Chinese economy was still in a state of partial hibernation. The tragedy of 4 June 1989 and the end of communist and high-socialist ideology as dominant factors in Chinese society gave birth to a deformed version of capitalism, with tiny windows that permitted individuals to go into business for themselves now that the state could not, and would no longer provide welfare to the more than 400 million urban residents of China. Among the bolder cadre of fledgling traders were the dealers in old and antique goods, antiques, fakes and copies who were making a modest living selling bits and pieces of old China mainly to foreigners and overseas Chinese, as only a tiny handful of Chinese on the mainland could afford to dabble in such impractical commodities at the time. That situation, of course, has changed radically, and today domestic buyers of all Things Chinese dominate the international trade in major and minor Chinese antiquities. A tiny cohort of those pioneering dealers were in the old-paper business, purveying Qing dynasty string-bound books, Republican magazines and monographs, Cultural Revolution posters, pictorials and documents, red-covered books of all types, and soft-propagandistic art books, printed on expensive imported paper. (Note: When I worked in the Foreign Languages Bureau in Beijing in the early 1980s, I was shocked to learned that over 60 percent of the bureau's entire budget was spent on imported paper.) At first, the book dealers plied their profession at Panjia Yuan 潘家园 Market, Liulichang 琉璃厂, and Baoguo Si 报国寺 in Beijing and in Fuzhou Lu 福州路, Dongtai Lu 东台路, and the Chenghuang Miao 城皇庙area of Shanghai. But by the late 1990s, virtually every city in China had its own Curios City (guwan cheng 古玩城), similar in nature to longstanding Hollywood Road in Hong Kong—tiny shops, piled with goods, no written prices, bargaining essential, strikingly improved service for repeat visits. Initially set up as tourist attractions for foreigners, the Chinese curiosity shops matured quickly and became the base for today's highly sophisticated trade.  The earliest non-local customers for 'serious' academic and documentary material, were embassy and consular China hands, Sinologists, undergraduate and graduate students in China, resident and visiting academics and journalists and the occasional book dealer or spy. Because the trade was conducted in spoken Chinese, and required customers to demonstrate a knowledge of written Chinese, those foreigners who showed a serious interest and who bought significant amounts of material were accorded great respect, and assigned clever nicknames, by the dealers, who were less individually competitive than co-conspiratorial in the tradition of the Chinese guilds. The early shops were unsystematic and generally a mess, with a few exceptions. Compared to Tokyo, with its weekly book markets in Kanda 神田 and elsewhere in Tokyo, an endless stream of detailed catalogues, Chinese book shops were, well, borrowing a phrase from Sun Yat-sen, a plate of loose, and often moldy and torn, pages. Where did the material come from? Mining the PastFollowing in the wake of Deng Xiaoping's modernization policies, ministries, bureaus, departments, committees, schools, hospitals, associations and private citizens shed their Cultural Revolution skins and the trappings of earlier lives. Entire archives and the holdings of libraries, reading rooms, 'cultural stations', filling thousands of burlap sacks (many formerly used for fertilizer and poultry feed) stuffed to the brim with personal dossiers, letters of introduction, written confessions, letters of transmittal, internal memoranda, personnel lists, inventories—variously marked 内部 (neibu, restricted circulation), 秘密 (mimi, secret), 机密 (jimi, classified) and even 绝密 (juemi, top secret) from civilian, police, military, government and religious sources, and even from defunct embassies and consulates in China, came onto the market, providing enough material for 25,000 PhD students per year for the next 250 years. Among the discards one could also find publications from an odd assortment of nations including Albania, North Korea, East Germany, the Soviet Union and her satellites, Cuba, Vietnam as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong , Macau and Singapore. It was as if an entire generation of documentation, from the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 until Deng Xiaoping's rise in 1978 was, by order from the top, to be consigned to the incinerator or scrap heap of history. While some of this material reached the dealers directly via their acquaintances and counterparts in the institutions, another major source for the book dealers were the wholesale scrap dealers, who stepped in with their sharpened antennas and retrieved from these massive consignments of printed paper what was valuable and sellable. As China revived, reconstructed—and regurgitated—in the 1980s, virtually every Chinese danwei 单位 or 'work unit' moved to new quarters, expanded their offices, got new coats of paint, and hired more workers. In this massive expansion project, there was little money, not to mention concern or awareness for the conservation, preservation or storage of old books, magazines and files. Rather, in the new capitalism-tainted climate, the cashflow went for living accommodations, automobiles, photocopy machines, weekend research trips to Macau and Hong Kong, and sumptuous business banquets at the restaurants and hotels that flourished with the new economy. At worst, old books with their outmoded ideological contents became obstacles to modernization, and new books and magazines were being written and published in such variety and quantity that if danwei didn't buy them, who would? As shortsighted as this was for the Chinese historical record, it was a godsend for collectors and dealers like myself. Fortunately, the birth of a new generation of dealers made it possible for much of this discarded material to circumvent the black hole of the official bookstores, such as the nationwide Cathay Bookstore (Zhongguo shudian 中国书店 ), which for several decades until around 1987, had a monopoly on the purchase and sale of old books and other printed matter. Today, Cathay/Zhongguo shudian in Beijing is one of several companies that holds regular auctions of rare books, and sells new books on its informative website (www.zgsd.net). In the mid-1990s, Cathay had at least one warehouse in Beijing for its old periodicals, located in a large underground fallout shelter in the southwest part of the city, with a dozen large rooms filled with books on shelves and dangerously moldy air. I was invited there once to search for children's books, and was able to purchase entire runs of bound early-Republican children's magazines for sensible prices. The contents of that fallout shelter were later moved to a two-story barn-like structure above ground that was lacking in heating, air conditioning and leak-proof walls and windows.  Once I made my general needs known, 'my' dealers astounded me by their resourcefulness, industriousness and entrepreneurial chutzpah, producing in a matter of weeks precisely the sort of material I had requested. In addition to the more obvious sources mentioned above, one shrewd dealer, who in recent years opened his own auction house, moved intelligently up the supply chain and contacted the family of a famous, late children's book author, editor and publisher, from whom he was able to purchase over 2,000 titles from a major 'youth and children's' publishing house, all dating from the early 1950s through the 1970s. Other dealers sought out school principals and former teachers, children's illustrators and authors. These were the days before the Internet, when telephones were far from universal, and people actually had to meet face to face to conduct business. Today, of course, taobao.com and kongfuzi.com, which operate much like amazon.com and ebay.com, have hundreds of thousands of books for sale online. Another group of smart dealers offered me a collection of 1,300 public health posters, dating from 1950 to 1976, from the archive of a major metropolitan hygiene department, which had obtained the posters by means of exchange with smaller hygiene bureaus and departments on the provincial, county and prefectural level, throughout China. The posters, bound in brown-bag paper volumes, are mostly printed in Chinese, but there are also posters from Tibet, Xinjiang and the Korean-speaking counties in the Northeast in local languages. The posters deal with the key health issues facing China in the early decades of the PRC: Schistosomiasis (or snail fever, Chairman Mao's famous 'god of plague' wenshen 瘟神), tuberculosis, handling of nightsoil, avian and swine flue, birth control and eugenics, food hygiene, eye exercises… . Arguing that the posters document the hygiene movements that account for one of the greatest population explosions in world history, I was able to place the poster collection and several thousand other items related to Chinese health, nursing, child-birth, opium addiction and sex education with the world's largest medical library in Washington, D.C. Interestingly, over eighty-five percent of the more than 50,000 children's books and magazines that have passed through my hands bear the marks, stamps and/or card pockets of libraries or danwei past and present. While books published in China up until the mid-1990s (when publishers lost state support and had to sink or swim based on sales, and thus increase production values), have always been relatively inexpensive, it appears that very few private individuals collected children's books, or kept them beyond the childhood of the reader. Print runs for illustrated childrens' 'chapter' books published by leading houses in Beijing and Shanghai in the 1950s and 1960s rarely exceeded 100,000 copies, and many titles were issued in the low ten-thousands. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, especially, paper and ink shortages and low paper quality reduced print runs of some books to 5,000 or less. In that era of highly questionable, and often quite deadly, statistics, such numbers are naturally open to suspicion. On the other hand, the most popular, and widely distributed books in China before and after the Little Red Selected Quotations of Chairman Mao 毛主席语录 of the mid-1960s to early 1970s were the small illustrated comic books (连环画, 小儿书, 小人书 ), read by 'children of all ages', with print runs that exceeded several millions. This is a topic worth pursuing in its own right. For some dealers in China, mastering the concept of 'condition' was a challenge. I recall one Tianjin man with a good supply of children's magazines who managed a single stall or tan'r 摊儿 consisting of two square meters of cold concrete under the huge roof at Panjia Yuan, who seemed unable to distinguish which of the books in his stock were filthy, moldy, rotten, splitting at the seams, overly fragile, or lacking key pages. It was during one of my mini-lessons with him in the basic skills of book connoisseurship, just as I was trying to explain how a book without a front or back cover, where the publication data was found, was of little value to me—that he tore off a page from one of the well-worn children's book at his feet and rolled a cigarette with it. Exporting China By the turn of the millennium, the flow and exchange of material in the antiques and curios markets had become increasingly liberalized, and shops in the major cities were displaying and selling with impunity everything from high quality archeological material to the finest fakes. Freshly unearthed Chinese antiquities, including archeological jade, bronze, ceramics, textiles and lacquer, once available only in Hong Kong, no longer needed to be smuggled across the border to Macao, and could be purchased in places like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. There was even a rumor about that as a way of competing with their mainland counterparts, dealers in Hong Kong boasted that customers could actually 'order' archeological items from any of the digs scientifically described in the authoritative mainland magazines, Cultural Relics (Wenwu 文物) and Archaeology (Kaogu 考古) and said items would be delivered to Hong Kong in a matter of weeks. Chinese police, army and Customs officials were allegedly pro-active in all categories of smuggling in and out of China—from tomb jades and gold bars and heroin to entire oil tankers and naval ships packed with Japanese luxury cars. There were rules on the books governing the export of cultural relics; at one point, 1798 (the third year of the Jiaqing 嘉庆 reign of the Qing dynasty) was the critical cut-off year for antiques, anything manufactured before that date requiring a Customs seal to be exported, but I was only offered one or two books from the eighteenth century in my fifteen years of buying in China. More recently, a rule appeared stipulating that anything manufactured before 1949 in any material (skin, cloth, paper, glass, metal, stone, wood, lacquer, etc.) had to be submitted to the Cultural Relics Bureau for examination before permission to export would be granted. But enforcing such a rule seemed absurb. While every antiques and curios market in China (Panjia Yuan in Beijing alone boasted over 1,000 dealers on weekends) was filled with clocks, furniture, clothing, sculpture, housewares, books, games, toys, jewelry and every kind of tschotske, bauble, trinket and notion imaginable from the first half of the twentieth century and a few decades before, there were no signs or instructions posted in any language making that pre-1949 rule known to the buying public, and, evidently, no Customs or Cultural Relics Bureau (Wenwu Ju 文物局) officials available on site to check what was being sold and bought. Dealers, too, were generally ignorant of the details of such rules. And thus it would seem commonsensical that in the absence of any visible rules or regulations to the contrary, everything sold at these markets, in a country reputed for its skills in policing human activity, was acceptable for export, given that foreign tourists were actively welcomed at such markets. For years I never had any problem, actual or conscience-wise, in sending the books I bought out of China. Until one enlightening encounter in 2003. The Raid of the Lost LibraryDuring the process of a home move from Hong Kong to New York, I had accumulated a large amount of printed matter in China, the fruit of some six-to-eight visits over the course of eighteen months to the many markets I shopped in. My assistant in China, Suzanne, had stored, packed in three one-cubic-meter crates, and arranged the shipping by sea to the US for me of these materials. However, the shipper delayed the dispatch without explanation, finally reporting to Suzanne after several weeks that there was a problem with the contents of the shipment.  A few days passed, and Suzanne, who worked for me part time as a liaison with the shipper and the dealers, informed me that her office had been raided by a dozen plainclothes officers, who confiscated her computer's hard drive, personal address book and passport, and rifled through her desk drawers. They muttered darkly about 'smuggling state secrets' and left her with a warning: 'That foreigner you work for is in serious trouble, and better never come back to China'. They also gave her a telephone number on a card and the surname of the person she could contact. She was naturally terrified by this rude intrusion, and confused about the reason for it, as the gentlemen in the possee hadn't given her specific information, nor did they detain her. She told them (truthfully) that she had been storing books for me in an empty room in her office building for over a year, while I searched around New York for a warehouse to store the material, but as most of the smaller boxes of books making up the shipment had been sealed by me, she was not aware of their specific contents and had not gone through them. I was in New York in the time, fortunate to be out of Hong Kong in a time of SARS, but became intensely paranoid when, one week later, Suzanne faxed me an article from a Chinese tabloid newspaper, which included the following contents (my summary), under the title 'Customs Intercepts Historical Material from the Anti-Japanese War: A Cause for Profound Concern by Collectors' (Haiguan jiekou Kangzhan shiliao: yinqi shoucanzhe shenceng sikao 海关截扣抗战史料: 引起收藏者深层思考): The Customs of a major city had seized a shipment of books and other goods heading for the United States. With the assistance of the Cultural Relics Bureau, it has been determined that the shipment contains cultural relics of national value. According to the law, 'All important or representative documents and cultural relics, etc., that pertain to the Chinese nation's [Zhonghua minzu 中华民族] fending off foreign insult, or resisting foreign aggression, or relate to noted personages, belong to the category of cultural relics that must be protected [by the state], and may not be exported. According to this report, the shipment contained a 'stunningly large and rare' (ziliao zhi duo zhi han ling ren zhenjing 资料之多之罕令人震惊) collection of 'material testifying to the Japanese invasion of China during the Anti-Japanese War [1937-45].' The sender of the shipment described himself as a 'Hong Kong person', [I was not named, nor was my English name transliterated into Chinese, but I did give my actual Hong Kong address as the 'shipper's address'.] The shipping manifest falsely claimed that the contents of the three cubic-meter crates were 'children's books.' Who would risk life and limb to attempt to smuggle such a vast collection of anti-Chinese material out of China? After describing a number of magazines, photographs, maps and posters attesting to the depredations of the Japanese military in the Republic of China, one collector who was quoted surmised that a number of 'die hard anti-Chinese elements' in Japan had collaborated with a number of book dealers in China, accumulating a large trove of printed evidence of Japanese crimes against the Chinese people, merely in order to destroy the explicit evidence of these crimes. At the same time, not everyone overseas who collects material about the Anti-Japanese War has pernicious motives. In 2001, a Chinese person living in the United States spent 'hundreds of millions of US dollars' to establish a 'Japanese Invasion and Holocaust Memorial' in Washington, DC, dedicated to exhibiting, researching and collecting material on the subject, and have sent teams to major Chinese cities to purchase material related to the subject. Their presence has been felt at auctions. In the report a university professor was named and quoted as having examined the material along with the Customs officials. He had supposedly verified that it was a significant corpus of material of extremely highly value to researchers. Said professor was to perform triage on the material, distributing the most important contents to the relevant departments and research institutions, and offering the remainder for sale to the public at auction.  The article upset me because it was, frankly, absurd. It was clear that the report was describing some aspects of my shipment, and the crude action that victimized Suzanne seemed to bear this out. But there were too many discrepancies between the article's description of the contents of the shipment and what was actually there, not to mention other fictional accretions. In describing the 'Japanese Invasion and Holocaust Memorial', was the journalist, possibly for the first time in Chinese history, viciously or ignorantly confusing the Japanese military with the Jewish victims of the Holocaust? Furthermore, as far as I could recall, the only items in the shipment related to the Anti-Japanese War were a handful of popular Japanese pictorial magazines from the period, which appeared from time to time in the markets, and were sold for less than USD2 per volume. The sort of Japanese war maps, books and pictures described by the article were precisely the kind of items that had been appearing in Chinese rare book auctions over the past few years, selling for the same price as in Japan; in fact, the descriptions in the article read like the descriptions in an auction catalogue. And it seemed ridiculous to me that those magazines should have been confiscated, not to mention be considered valuable, since pictures from periodicals of this sort were being reprinted in big Chinese books with titles like History of the Anti-Japanese War in Pictures. At this point, all I wanted was to recover my books and to clear Suzanne of any wrongdoing. So, I asked Suzanne to call the name and number on the card she had been given and ask them how they wished to proceed. At the same time, since my head was starting to reel from the outlandish lies in the article and the cloak and dagger nonsense taking place at Suzanne's and my expense, I contacted an acquaintance who was a former US State Department official with extensive experience in China. He is a man with a great sense of humor, openness and warmth, to ask his advice on how to proceed as painlessly as possible. The man at the other end of the line replied quickly to Suzanne that I should write a confession, and that it should offer information on the potentially serious offense that I had committed: exporting 'state secrets' from China. They had specifically mentioned that they were concerned about the datou wenjian大头文件, documents with 'headlines in a large font' for elderly cadres with failing eyesight, issued by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, and widely distributed during the Cultural Revolution. Heaps of just such documents, their contents now appearing like so much political mumbo-jumbo after 35 years on the junk heaps, were available for sale by weight in the various book markets in China. The official did not mention anything about Japan. The detail about the datou wenjian also disturbed me. I was aware that, in 2003, the Chinese University of Hong Kong had compiled for sale a CD ROM filled with jpg files of these very documents. Entitled The Chinese Cultural Revolution Database CD-ROM, it was issued in seven parts, with 'first-hand sources to tally to 30,000,000 words'. Part I contained 'CCP's Documents, Directives, and Bulletins Concerning the Cultural Revolution', the very sort of documents that had pixilated the security people in China. One would note that Chinese University was a public institution firmly located on Chinese soil. It was also an institution with which I was very familiar, having been employed there as an assistant editor at Renditions magazine for four years in the 1980s. Regarding the picture books, maps, postcards and magazines published in Japan and Manchoukuo during the 1930s and 1940s that were being sold at rare book auctions, such as at Cathay Bookstore, I learned from book dealers in Tokyo that buyers from Mainland China were coming to their shops and sales and purchasing this kind of wartime material, which was inexpensive and unpopular in Japan, but which seemed to have a growing audience in China. Yes, indeed, the material provided clear evidence of Japanese imperialists' invasion of Japan. So while I—having been suspected of collusion with diehard Japanese Right Wing reactionaries—was busy exporting wartime material from China as a way of hiding nasty evidence, Chinese traders were similarly engaged importing it from Japan to China and making the same evidence known, and at a profit to them and the Chinese auction houses, some of them government-run. The true absurdity of this sword-and-shield international trade was only confirmed to me by my interrogators, as will be discussed below. My Day in CourtIn my Chinese confession, which Suzanne helped translate and tailor to local etiquette, I outlined my forty years of China study, twenty-five years living and working in China and Hong Kong, my travel business in China (I had organized 175 tours that brought around 2000 people to China since 1979), my writing and translation work, and suggested that they consult my dossier at the Foreign Languages Bureau in Beijing, where I had worked from 1981 to 1984. I described my formation of the Asian children's book holdings of the Cotsen Children's Library, and my authorship of a monograph on Chinese childrens' books published by the library. I stressed my close relationship to China on a family, personal, business and professional level, and threw in the fact that I had consulted with close friends in the US State Department and the US Embassy in Beijing on the matter at hand. Conferring with my US contact, I decided that while I felt confident that the charge against me had a bark worse than its bite, I had no interest in setting off an international incident. More than anything, I wanted to continue traveling to China and acquiring Chinese books; in that regard, I had long-term obligations to over a dozen dealers. The naïve assertions of the newspaper article were nothing more than a group of trills and appoggiaturas ornamenting the rather dim-witted dirge-like progress of nationalism. Regarding the sensitive material I had attempted to export, I wrote that everything in my shipment had been purchased from approximately thirty dealers who had shops at public markets in Beijing, Xi'an, Shanghai, Tianjin, Guangzhou, and Urumqi. Finally, I stated my willingness to go to China once the World Health Organization determined that the SARS threat had diminished sufficiently to make travel safe, and to meet with them to regain possession of my books. I also asked for assurance that my movements would not be circumscribed in doing so. Suzanne submitted the document, and had to wait several weeks for a reply, which was positive: they would meet me when I came to China, and I didn't have to worry about my safety. So, in late April 2003, Suzanne and I headed for a meeting in a large Chinese city. I controlled the butterflies in my stomach by reassuring myself that I had in my pocket the direct phone number of the US Ambassador in Beijing and the US State Department China Desk. To support my case, I also brought with me the printed brochure for the Chinese University's CD ROM of Cultural Revolution documents, and several Chinese auction catalogues with Japanese-published books, photographs and magazines from the period of the Anti-Japanese War. We were met at a four-star hotel by four men aged from their thirties to fifties, and moved to a suite. It was a grey early spring day, overcast, and the men seem to have walked directly out of the ambivalent weather. The two middle-aged men did nearly all the talking; the youngest man acted as stenographer; and a fourth, elderly fellow, evidently the most senior sat and listened to the entire interview, only speaking up at the end of our session. I had initially contemplated insisting on speaking English, if indeed the charges they were going to bring against me were serious to the point of life-threatening. But after a few minutes of speaking in Chinese, their cordiality and mixture of self-importance and boredom put me at ease, and I agreed to answer their questions in Chinese for the record. The session began with their telling me that they had received my confession, and had read it very carefully. After reminding me of the potential seriousness of my offenses, they asked me pointedly where I had bought the sensitive material. I told them candidly that since the purchases had taken place as long ago as 2-3 years ago, and that I had made many visits to many dealers in many markets, and that there with three cubic metres of material, it was impossible for me to recall exactly who sold what to me when. I did show them the Chinese University CD ROM brochure, and they were straightforward enough to acknowledge that they did not know about it, but brushed aside the issue of public access to Chinese documents by telling me that: 'We look at things like that differently in China.' I let the matter go, but clearly I had won a point. They then took out the eleven items that had been impounded from the shipment.

Taking a very deep breath, as much a sigh of relief as a source of oxygen for a belly laugh, I interrupted the interrogation process and said: So is that the great Anti-Japanese collection I read about in the newspaper article? I had mentioned the article in my confession, and they acknowledged that they had also read it. I told them that at most there were three or four Japanese wartime magazines in the boxes, but they had not taken them out to show me, probably because they only looked through one of the three boxes.  Their reply was unforgettable. The senior gentleman, speaking for the first time, said to me: There's no Anti-Japanese material here, and in any case it's no problem to export that kind of book or anything about the Anti-Japanese War. In China, as you know, things aren't always what they appear to be. That article was fabricated by a journalist in cahoots with the Customs. Before the Chinese New Year, the Customs department offers financial rewards to underlings who discover plots to smuggle important relics and data out of China, as a way of stirring up patriotic fervour. At the same time, newspapers offer financial incentives to journalists who write about such things and who stir up such feelings among their readers. Whether the transgressions occurred or not doesn't matter. What matters is that The People learn via the media that the Customs is doing a good job. 'By crushing the Japanese imperialists', I added. We all laughed, and the ice was broken. The leader made it quite clear that he held the Customs people in the greatest contempt. A Way OutMy testimony, in about eight pages, was presented to me after a one hour lunch break, and I appended my thumbprint in carmine seal ink to it. In addition to most of what I said, they had added, writing in the first person, that I had committed a very serious crime that would normally merit grave punishment, but that considering the circumstances of my long time connections to China, and my forthright confession to them, they would wave any punishment—something that was not specified (and I didn't ask what it might be). As the stenographer read the passage about 'serious punishment' to me, the four mens' eight eyebrows contracted contrapuntally in a mass calesthenics display of pain and contrition. They also told me that I was welcome to continue operating tours in China, and buying children's books, but that I should not attempt to send sensitive material out of China again. As we parted with an earnest 'Tut, tut, tut' from the cadres, the senior gentleman actually put his arms around me and offered me a friendly bear hug—I checked for a bug on my back later, but there was none, and he told me that if I ever needed anything in his city, I should contact him; I similarly invited them to visit me in New York. They told me that I had to pay a Customs storage charge of about USD250, which won my books the right to sail to America. When the three wooden crates, each a cubic meter in size, arrived in New York two months later, it was evident that the contents of at least one of the boxes had not only been 'opened for Customs inspection', but also had been ravished on a muddy, wet floor, and then haphazardly tossed back into the crate, resulting in crushed spines, torn posters, stripped covers, missing pages, etc. Notably, one volume of a four-volume set of Mao's selected works was missing from the shipment, but otherwise it seemed that nothing save the eleven sensitive items had been removed. The saddest addition of all was the imprint of muddy boot soles on children's classroom posters and textbooks, evidence that the Customs people had strolled like giants on the very objects they were inspecting, Goliath leaving his footprints on David's face. Such was their heroically fruitless search for a precious cache of Anti-Japanese material among a shipment of kid's books. |