|

|||||||||

|

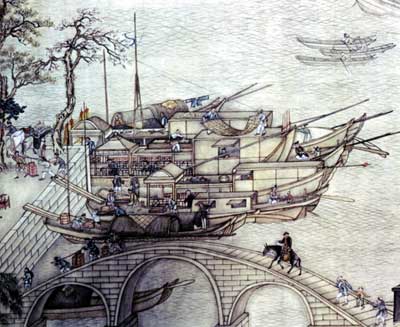

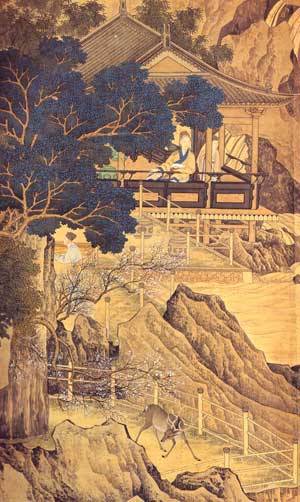

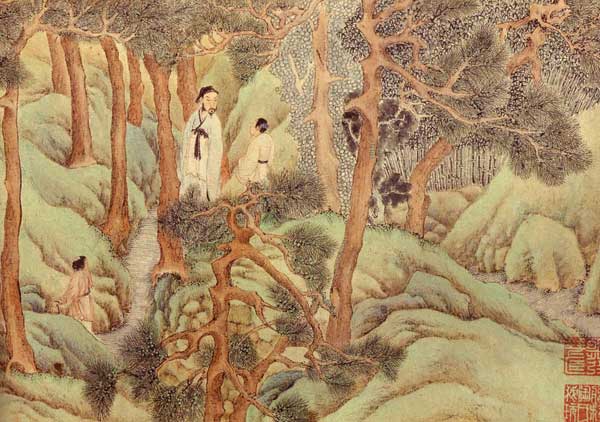

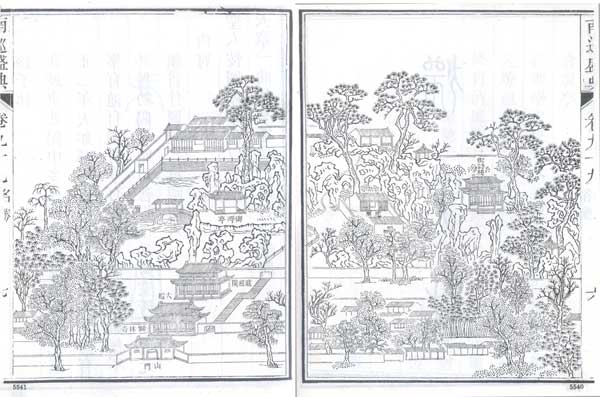

FEATURESAcquiring Gardens Fig.1 Suzhou sailing vessels of the zuochuan type moored on the Grand Canal, Qing painting by Xu Yang, Gusu fanhua tu, illustration courtesy Illustration from Wang Guanzhuo ed., Zhongguo guchuan tupu, Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, 2000, colour frontispiece. In the course of nearly one and a half millennia, various dynastic capitals—Kaifeng, Luoyang, Hangzhou, Nanjing and Beijing—were located on or adjacent to the Grand Canal. The rulers in these political centres sought to patronise or acquire the best of the nation's culture, so it is hardly surprising that distinctive cultural features of different regions spread to the capital of the day along the canal. Two of the signature cultural properties of Beijing today—Peking duck and Peking opera, both travelled to the capital via the Grand Canal—Peking duck from Shandong province and Peking opera from Anhui. However, Qing dynasty other aspects of the culture of Beijing and its environs that had 'travelled' there via the Grand Canal continue to be regarded as typically 'southern.' An example we examine here is the Suzhou-style garden with its fantastically shaped rocks and expansive vistas created within limited confines. This cultural feature, inspired by private gardens seen in southern China by the Qianlong Emperor (r.1736-1795), made its major entrée to Beijing via the Qing imperial garden palace, Yuanming Yuan (the Garden of Perfect Brightness, see issue no.8, December 2006 of China Heritage Quarterly).  Fig.2 Jin Tingbiao, Hongli gongzhong xingle tu (The Qianlong Emperor enjoying his pleasures in the palace), transverse scroll, detail. Source: Gugong Bowuyuan ed., Gugong Bowuyuan cang Qingdai gongting huihua (Qing palace paintings in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing), Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, 1992, p.192. During his sixty-year reign, Qianlong undertook six tours of inspection through southern China, taking him to the major cities of Jiangning (now Nanjing), Yangzhou, Wuxi, Suzhou and Hangzhou (see 'The Southern Expeditions of Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong' in the Features section of this issue). (Fig.1) Aside from the duties incumbent upon him as the ruler of the Manchu-Qing empire, the emperor clearly took great pleasure in the south and its natural and manmade landscapes. His southern tours of inspection also represent the pinnacle in this enterprise developed by his grandfather, the Kangxi Emperor (r.1662-1722), and one of the most tangible reminders of the south for Qianlong were the four southern-style gardens that he had constructed in the vicinity of the Yuanming Yuan garden palace and its environs north-west of Beijing. Yuanming Yuan was the garden palace complex gifted by the Kangxi Emperor to his fourth son Yinzhen, the future Yongzheng Emperor. However, it was in 1744 that his grandson Hongli, the Qianlong Emperor, set about creating vistas which were near replicas or faithful evocations of impressive private landscaped gardens which the Qianlong Emperor had visited in the course of his journeys to the south. The most renowned of these were four southern gardens, the 'Ten Vistas' inspired by the West Lake of Hangzhou, Anlan Yuan (Tranquil Wave Garden) in Haining, Jichang Yuan (Garden Conferring Pleasure) in Wuxi, and the Forest of Lions (Shizi Lin) in Suzhou. (Fig.2) Although the existence of these acquired gardens is well documented and the general outline of what the Qianlong Emperor achieved in these northern replica gardens are clear, architectural historians have yet to examine the actual process of by which this imperial acquisition took place. This is a reflection of the relative anonymity of the landscape gardener and even of the architect in Chinese history. What remains of these imitative gardens today are the poems, essays and paintings that celebrate them, although these often depict ideal, rather than real, individual gardens. (Figs.3&4) Scholars have not yet examined in detail the records of the imperial household with a view to studying the accounts of expenditure on the replica gardens, the commissions issued to gardeners and the acquisition of rocks, plants and materials for use in their construction. The partial destruction of Yuanming Yuan in 1860 and the subsequent dismantling and neglect of the immense site also ensured that little attention was paid to the fate of individual elements of the complex.  Fig.3 Scene from a typical Suzhou garden. Zhuozheng Yuan, Suzhou [BGD]  Fig.4 Another scene from a typical Suzhou garden. Zhuozheng Yuan, Suzhou [BGD] The majority of Qianlong's landscaping innovations and introductions were focused in the eastern section of Yuanming Yuan, where, by 1751, he had basically completed construction of a Chinese-style complex of gardens, which he named Changchun Yuan (the Garden of Prolonged Spring). It occupied an area of approximately 70 hectares and was named for one of the buildings in Yuanming Yuan proper called Changchun Xianguan (the Lodge of the Immortals of the Prolonged Spring), where he had grown up as a young man under his grandfather's tutelage. He prepared the new garden complex as the residence for his retirement, so it had none of the characteristically complex architectural structures of the Yuanming Yuan which had to function as both political work places and residences. Changchun Yuan was designed to provide tranquillity and solitude. Ironically, the gardens of southern China, epitomised by those of Suzhou, were, in fact, originally inspired by gardens in the vicinity of Beijing, created by the early emperors of the Ming dynasty who sought to reassert agriculture and agricultural policy by example in the western parts of the capital that had been transformed by the Mongols into a hunting park. The Suzhou garden, which came to epitomise the ability to create spaces for philosophical retreat, aesthetic transcendence and desirable connoisseurship in urban settings, is often depicted as the exemplification of the Daoist ideal of man and nature in harmony. Yet the economic, cultural and social origins of the Suzhou garden, among a class of scholar-officials who were simultaneously also what we might describe anachronistically as serious-minded hobby farmers of the early Ming period, represent one local interpretation of a political economy originally practised in Beijing.[1]  Fig.5 Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) made many paintings of Suzhou gardens in the Ming period. This is a detail from his painting of the garden at Huishan, Wuxi, Huishan ronghui tu (Gathering of personages at Huishan) in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. Source: Zijincheng (Forbidden City), no. 140, July 2006, p.32. However, the veracity of the relationship between gardens visited by the emperor in the south, and those of the same name he created at Yuanming Yuan, can never be known, except through the idealised vistas that appear in several albums of paintings and woodblock illustrations. Few scroll paintings depicting the replicated gardens, either before or after, survive. (Figs. 5&6) Yet the fact that many of Qianlong's artistic exercises entailed a passion for faithfully transforming objects from one artistic medium into another would suggest that the gardens of the south that he sought to acquire through replication were veracious reproductions of originals.[2]  Fig.6 Detail of Wen Zhengming's Huishan ronghui tu. Source: Zijincheng (Forbidden City), no. 140, July 2006, p.32.  Fig.7 View of the Tuisi Garden in Tongli outside Suzhou. This garden is said to have been established in the Ming dynasty. [BGD] By the time Ji Cheng's work on the theory and practice of landscape gardening titled Yuanye (The craft of gardens) had been compiled at the end of the Ming dynasty, a theory of garden culture and its associated aesthetic had emerged in China. Born in 1582 in Tongli (Fig.7), a canal town not far from Suzhou, Ji Cheng systematised a tradition of horticultural and related writing to which many Ming scholars, including the 'Gongan School' essayist Yuan Hongdao (1568-1610), contributed. Ji Cheng's Yuanye may have been consigned to obscurity, because the preface was written by the notoriously corrupt Ruan Dacheng (1587-1646), but it is also the articulation of professional knowledge in its time. We can assume that the Qianlong Emperor was in a position to gain access to the information contained in Yuanye, even if we have no record of the emperor referring to this particular text. The fact that two of the four southern gardens—Shizi Lin and Jichang Yuan (Huiyuan) (Figs. 8&9)—which the Qianlong Emperor recreated in Yuanming Yuan, have survived largely intact to the present day gives us some idea of the originals on which the imperial copies were based.  Fig.8 Woodblock illustrations of the garden at Huishan visited by the Qianlong Emperor. Source: Nanxun shengdian, Taipei: Xinxing Shuju, 1979, pp.5518-9.  Fig.9 Woodblock illustrations of the Shizi Lin garden in Suzhou visited by the Qianlong Emperor. Source: Nanxun shengdian, Taipei: Xinxing Shuju, 1979, pp.5541-2. The Forest of Lions Fig.10 Scene of Shizi Lin, Suzhou [BGD] The creation of the garden complex in Yuanming Yuan that came to be known as the Forest of Lions (Shizi Lin) began with the establishment of a small courtyard in Changchun Yuan where a pavilion jutted out into the water. Accessible by boat, the pavilion was named Yangyue Ting by the Qianlong Emperor. Behind it stood a hall, as well as a belvedere and studio surrounded by ancillary buildings on three sides. The belvedere and studio, which eventually were named Congfang Xie (Belvedere of Verdant Fragrance) and Jingxiu Zhai (Studio of Respectful Cultivation), respectively, were built in 1747, and these first structures would later be augmented on their eastern side by the landscaped stone garden called Shizi Lin (Forest of Lions), the name eventually applied to this landscaped area. The original western section, as depicted in prints and paintings of the period, of what would become the Forest of Lions bears no resemblance to the private garden in Suzhou, but the eastern area constructed later was described as a faithful replica. The entire Forest of Lions in Changchun Yuan was not completed until 1772 (some sources say 1777), after the Qianlong Emperor's fourth expedition to the south. However, the emperor was so delighted by the creation of his garden architects in Beijing that, only two years later, he ordered that a second replica of the Forest of Lions be built at the Imperial Hunting Lodge (Bishu Shanzhuang) in Jehol (Chengde).  Fig.11 Scene of Shizi Lin, Suzhou [BGD]  Fig.12 Scene of Shizi Lin, Suzhou [BGD] The eastern section of the Forest of Lions in Changchun Yuan, like its namesake in Suzhou, is said to have been ultimately inspired by a landscape in a painting by the Yuan dynasty artist Ni Zan (1301-1374) entitled Shizilin tu (A forest of lions), in which small buildings are clustered among artificial outcrops of Taihu rocks that appear to have been tossed up like billows of ocean spray. The rocks are of the characteristically unusual form collected from Lake Tai (Taihu). However, the Forest of Lions in Changchun Yuan was largely destroyed in the conflagration of 1860 and many its Taihu rocks were gradually removed over the course of the subsequent century. The inscription 'Forest of Lions' in the hand of the Qianlong Emperor remains on a stone plaque is still in situ, and a forlorn stele inscribed by the Daoguang Emperor (r.1821-1850) is a further sorry reminder of its subsequent fate.  Fig.13 Scene of Shizi Lin, Suzhou [BGD]  Fig.14 Scene of Shizi Lin, Suzhou [BGD] The only sense of the former glory of Qianlong's Forest of Lions can be gained from the garden of the same name extant today in Suzhou. (Figs.10,11&12) Now one enters the Forest of Lions in Suzhou from the far south-eastern corner of the enclosed area, through what was part of a family shrine constructed in the early 20th century. The entrance is austere and confined, comprising only bare whitewash walls and dark simply carved timbers. (Fig.13) Only after passing through a shaded courtyard decorated with several gnarled ancient trees in pots and a strategically placed Taihu rock, suggesting a crouching animal form, do the bare elements of the original garden first present themselves to the visitor. (Fig.14) Located in north-eastern Suzhou, the original Forest of Lions is regarded as being representative of gardens of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) and was first laid out at the rear of Lion Forest Temple founded by the Buddhist monk Tianru Weize (1286-1354). Weize, whose surname was Tan, was a native of Yongxin in Ji'an, Jiangxi province and, as a young man, he went to study Chan (Zen) under Master Zhongfeng at Lion Crag (Shizi Yan) in the Tianmu Mountains of Zhejiang. Today Tianmu is better known as the name of a porcelain glaze (Temmoku) on the dark tea bowls used in the Chan (Zen) art of tea. After Weize had studied for more than twenty years in the Tianmu Mountains, he was presented by the last Yuan emperor, Shundi (r.1333-68), with the title Foxin Puji Wenhui Dabian Chanshi, signifying that he was a prominent and erudite Chan master. Students flocked to study under him. Weize moved to Suzhou, where his students purchased ten mu, equivalent to 60 acres, of land to establish a temple. The temple was called Shizi Lin Puti Zhengzong Si (Lion Forest Temple of the True Bodhi Master). As was customary, a garden was established at the rear of the temple. As Ouyang Xuan (1283-1357) wrote in Shizi Lin Puti Zhengzong Si ji, 'In the city of Gusu [Suzhou], there is a grove called Shizi and a temple called Puti Zhengzong'. However, it was only later that the temple and the garden were separated. By naming the grove Lion Forest, Weize was honouring his teacher, Master Zhongfeng, and the Buddha, The lion is a salient image of the Buddha and the name recalled the location of the retreat of Weize's master. Following the introduction of Buddhism to China, it was customary for Buddhist temples and monasteries to establish groves in which teachers would lecture and train their students. This recalled the setting in which Gautama Buddha taught his disciples. However, almost from the time of its establishment, the Lion Forest Temple's garden also became a venue at which the secular literati of Suzhou would gather. Shizi Lin is most renowned for its sculpted rock formations or artificial mountains (shanshi), and this feature of the gardens is described in early writings by Ouyang Xuan, Zhu Derun (1294-1365) and Gao Qi (1336-1374). These artificial mountains were a feature of Shizi Lin from the time of its establishment by Weize, who wrote in his Shizilin ji jing (The Forest of Lions and its vistas), 'People say that I live in the city, but I imagine I am located among ten thousand mountains'.[3] Dating from the Yuan dynasty, the large group of unusual rocks arranged as a mountain riddled with caverns at the front of the belvedere called Zhibai Xuan has been described as the most renowned example of an artificial mountain among landscaped Chinese gardens. (Figs.15, 16&17) Mazes run through its peaks, crags, valleys and caverns formed from Lake Tai rocks, and these rockeries in Suzhou cover nearly half the total land area of the garden, which is said to include nine separate 'mountain trails' and twenty-one grottoes.  Fig.15 Scene of Shizi Lin, Suzhou [BGD]  Fig.16 Scene of Shizi Lin, Suzhou [BGD]  Fig.17 Scene of Shizi Lin, Suzhou [BGD] During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) the garden remained part of the adjacent temple, except for a brief period during the Jiajing reign (1522-66) when it seems to have been a private demense that attracted literati gatherings. In 1651, after the establishment of the Qing dynasty, we know that the temple garden was 'restored.' In 1703, during his fourth trip to Suzhou in the course of a southern tour of inspection the Kangxi Emperor paid a visit to the Lion Garden Chan Temple. He inscribed plaques for both the temple and the garden at its rear, but Wei Jiazan points out that at some time prior to 1679, the garden had become the property of Zhang Wencui and his son Zhang Shijun. The garden was now independent of the temple and it again became a venue for gatherings of prominent literati, including Zhu Yizun (1629-1709) and Zhao Zhixin (1662-1744). It was later acquired by Huang Xingzu, who served for a time as the prefectural magistrate of Hengzhou, and he renamed the garden She Yuan or Wusong Yuan, the latter meaning Five Pines Garden, a reference to one feature of the garden. When the Qianlong Emperor first visited Shizi Lin in 1757, he noted in a footnote to a poem titled You Shizi Lin that the garden was now the She Yuan of the Huang family. He praised the beauties of the place and had his artists draw sketches of it. On returning to Beijing, the emperor allocated 130,000 taels of silver to construct the replica garden in Changchun Yuan, and, later, a further 70,000 taels to construct the further replica in Chengde. It was not until the beginning of the Qing dynasty that a dividing wall was built between the temple and the garden, and the garden became a private villa. Yet while this change from temple garden to private garden saw a change in alignment from one in which the temple was in front and the garden in the rear to one in which there is a private shrine on the eastern side and a garden on the western side, the basic features of the garden itself did not fundamentally change. In documenting the changes the garden underwent in the 19th century, Wei Jiazan tells us that by the end of the Xianfeng reign (1851-61), the garden had fallen into complete decay and become overrun with weeds. More alarmingly, in the mid Guangxu period, the Huang family was bankrupt and 'the large timbers and rocks were sold off.' [4] The garden was eventually acquired by Bei Runsheng (1870-1945), who restored the garden and built a family shrine in it. Today, part of the family shrine and the living quarters are occupied by a museum of folklore. Jichang Garden Fig.18 Scene of Jichang Yuan, Wuxi  Fig.19 Scene of Jichang Yuan, Wuxi  Fig.20 Scene of Jichang Yuan, Wuxi Although the Forest of Lions was possibly the most beloved of the 'private' gardens that the Qianlong Emperor transplanted from the south, it was the Jichang Yuan, located in Wuxi, near the Grand Canal along which the imperial flotilla passed in 1751 that had first impressed the ruler. (Figs.18, 19&20) Jichang Yuan made spectacular use of two hills which bounded it—Huishan to the west and Xishan to the east. Jichang Yuan has been characterised by the Chinese garden historian Zhou Weiquan as 'a medium sized landscaped villa garden' (zhongxing de bieshu yuanlin).[5] First laid out in the Yuan dynasty as part of a Buddhist monastery, the garden later came into the possession of the powerful Ming dynasty minister Qin Liang who, in 1591, after returning from a journey to the Hu-Guang region, was inspired to create a garden with hills surrounding a lake. He named the garden Jichang Yuan, drawing inspiration for the title from an essay by the renowned calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303-361). At the beginning of the Qing dynasty, the garden was extensively remodelled and enlarged, and a number of the hills were augmented. The garden became renowned for the immensity it evoked, and during their southern expeditions both the Kangxi and Qianlong emperors were accommodated there. The garden was irregularly arranged around a lake, which occupied the eastern section of the space. The expanse of lake emphasized the expanse of hills that ringed it on its northern and western shores, and the reflections in the lake lent height to the surrounding hills. It was one of the most successful examples of trompe d'oeil created by Chinese landscape gardeners. The Qianlong Emperor first became acquainted with Jichang or Huishan Garden during his first tour of inspection of the south in 1751, and on his return to Beijing he set about having a replica garden constructed. It was completed by 1754 and the emperor composed as set of poems describing eight of the vistas in the replica: 'Of all the renowned villas of Jiangsu, the Qin Garden in Huishan is the most ancient, and one of my imperial ancestors [in the Ming] gave it the name Jichang. In the spring of the xinwei year [1751], I made my southern tour of inspection and was able to take delight in its subtle perfection (youzhi) and I returned to the capital with pictures of it. I then [had] copied the conception of these at the foot of the eastern side of Wanshou Mountain, and I called it Huishan Garden. Each pavilion and path afforded me a marvellous sense of harmony, and I have composed poems for eight of its vistas'.[6] Zhiyu Qiao (Knowing Fish Bridge—a reference to a famous episode in Zhuangzi) was a long bridge that was the best known of the five in the garden and Qianlong wrote poems which were carved on each of its columns. As he writes in one of the poems:

This and the seven other poems in the set celebrating Huiyuan Garden make it clear that the acquisition of such a garden also encompassed the acquisition of its literary and cultural associations. Here the emperor refers to Zhuangzi's debate with Huizi in the Qiushui (Autumn waters) section of Zhuangzi regarding the inability of an individual to presume to know the mind of another, occasioned by Zhuangzi's comment on yu zhi le: the delight fish took in swimming in the Haoliang River. Today we also have little idea of the nature of the replica Huishan Garden in Qingyi Yuan (the site of what would become the Yihe Yuan). It was renamed by the Qianlong Emperor's successor, the Jiaqing Emperor (r.1796-1820) Xiequ Yuan (Garden of Harmonious Interest). It was destroyed together with much of the Yuanming Yuan and the other four large gardens in western Beijing in the looting and razing frenzy authored by Anglo-French troops in 1860. Ironically, Jichang Yuan in Wuxi was also burned to the ground by rebel armies in 1860. Many of the buildings in the southern part of the Wuxi complex were never rebuilt, but Jichang Yuan in Wuxi has today recovered much of its former glory. The garden in Beijing which it inspired was again drastically remodelled in 1893 as the Yihe Yuan summer palace built for the planned retirement of the Empress Dowager Cixi. Verisimilitude aside, both gardens are nevertheless tributes to the art of Chinese landscaping and to the emperor who helped disseminate this art throughout China, indirectly creating the conditions which led to the introduction of Chinese gardening concepts to England and Europe. [BGD/© Bruce Gordon Doar] Notes:[1] This is a simplistic encapsulation of Craig Clunas nuanced thesis on the social and art-historical phenomenon represented by the Suzhou garden. See Craig Clunas, Fruitful Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China, Durham NC: Duke University Press, 1996. [2] Wang Guangyao, 'Porcelain imitating bronze: The porcelain Ban gui of the Qianlong period,' China Archaeology and Art Digest, vol.3 no.4, June 2000, pp.115-129. [3] Wei Jiazan, Suzhou gudian yuanlin shi (History of classical gardens of Suzhou), Shanghai: Sanlian Shudian, 2005, pp.169-70. [4] Ibid, p.179. [5] Zhou Weiquan, Zhongguo gudian yuanlin shi (The history of Chinese classical landscaped gardens), Beijing 1990; 2nd ed., Beijing: Qinghua Daxue Chubanshe, 1999, p.295. [6] Aisin Gioro Hongli, Ti Huishan Yuan bajing (Inscriptions for eight vistas of the Huishan Garden), Sun Peiren & Bu Weiyi, eds., Qianlong shi xuan (Selected poetry of the Qianlong Emperor, Shenyang: Chunfeng Wenyi Chubanshe, 1987, pp.130-2. [7] Ibid, p.130. Further reading:Chen Zhi annot., Ji Cheng, Yuanye zhushi (The annotated Technique of gardening), 2nd ed., Beijing: Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chubanshe, 2006. Wu Bihu, Liu Xiaojuan, Zhongguo jingguan shi (History of Chinese cultural landscapes), Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, 2004. |