|

FEATURES

A Tale of Two Cities | China Heritage Quarterly

A TALE OF TWO CITIES:

NEW MUSEUMS FOR YINING AND URUMQI

Fig. 1 Exterior of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining. [BGD]

The year 2004 marked the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Region in the far west of Xinjiang and, to celebrate the occasion, Yining, the region's capital, acquired a modern museum to showcase local history and cultures. (See Fig. 1) Thereby, in the wake of the scandals which closed down and led to the demolition of the old Museum of the Xinjiang-Uyghur Autonomous Region in Urumqi, Xinjiang as a whole acquired its only modern museum.

Fig. 2 Palaeolithic stone core from the Qiongkek site in collection of Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

The Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture covers an area of 350,000 sq k in the north-west of Xinjiang and has a population of more than 4 million. The Qazaq (Kazak) ethnic group is the "main" ethnic group in the prefecture, numbering more than one million. Of the 47 national minorities now living in the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture, thirteen can be described as original inhabitants: Qazaq, Han, Uyghur, Hui, Mongol, Xibe, Manchu, Daur, Russ (Russian), Qirghiz, Uzbeq (Ozbeq), Tartar and Tajik. Yining today is little different from other northern Chinese cities, although the old town preserves a predominantly Uyghur heritage. There is also a perceptible Russian architectural influence in the city, and in the dacha-style housing in the city's environs. Driving through the countryside of the prefecture, one sees many yurts that belong predominantly to Qazaqs and Mongols, but the owners are generally eager to rent these out to tourists to supplement their incomes. Unlike the oases of southern Xinjiang, the Ili river valley district is lush and amenable to farming and pastoral economies. The steppe, which covers most of the prefecture, is ringed by the towering peaks of the Altai and Tianshan ranges.

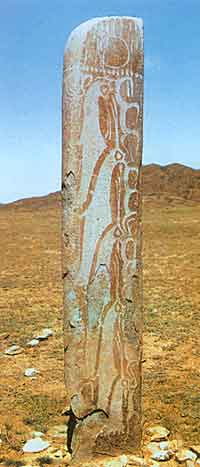

Fig. 3 Lushi or deer stone from Qiaerger, Fuyun county, in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

Fig. 4 Sample of white matter ore from Nurasai copper mine, Nilka county, in the collection of the Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

The museum comprises three major exhibition areas for the display of pieces drawn from the museum's collection of approximately 2,700 items. Since it opened to the public at the end of 2004, the museum has divided its exhibits between archaeological and folkloric displays respectively titled: "The Steppe, Heavenly Horses and Nomads" and "Ethnic Customs". Housing the offices of the Ili-Kazak archaeological team on its second floor, the museum's archaeological material is well presented, showcasing the many archaeological discoveries made in the Ili River Valley over the past half century.

The Ili River Valley has been a centre of steppe cultures over the past three millennia and the area has seen the passage of many nomadic groups and polities – the Iranian Saka, the Xiongnu, the Wusun, the Turks, ancient Huihu (Uyghur), Mongols, Xibe, not to mention the colonising Han Chinese and Russians. Over the past two centuries the Ili River Valley has also been a major stage on which Qing, Russian, Soviet and Republican-PRC international politics have been played out, with Yining (formerly known as Khuldja) playing a pivotal role in the resurgence of both Turkic-Uyghur identity and Sino-Russian tensions. Alimali (Turkic for "place of apples"), now a ruin at a strategic border crossing north-west of today's Yining city, was the political centre during the Qaraqanid empire, Jaghatai Khanate and the Qing dynasty. The governor-general of Ili was effectively the governor of Xinjiang during the early part of the 19th century.

Fig. 5 Bronze figure of Saka period unearthed in Gongliu county, in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

A curved bronze bas-relief surrounding the foyer of the new Ili Kazak Museum celebrates incidents in the history of the Ili River Valley: the military expedition of the Han-dynasty general Zhang Qian, the domination of the steppe by the Wusun, the return of the Turghot Mongols (Kalmucks) from the Volga River, the arrival of the Xibe people from north-east China, the suppression of Yakub Beg's uprising in the 19th century and the exile of Lin Zexu (famed for his ill-fated anti-opium trade activities) in Alimali. All these events hinged on the epic movement of peoples and armies, but the displays indicate that many skills of settled communities were developed in the region over the past five millennia. The museum well documents the archaeological record.

Fig. 6 Bronze cauldron in Ordos style from the Saka period unearthed in Zhaosu county, in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

Evidence has been discovered of microlithic cultures in the 3rd millennium BCE along the Ertix and Ili rivers which cross the steppe. Since 1989, five microlithic sites have been found around Qideharen on the Ertix river, and in 2002 microliths were also found under the cultural layers of the Qiongkek site (Fig. 2) on the Kax River, an upper tributary of the Ili River. The stone age art in the Ili region blends with some of the Turkic rock art of later periods. Deer stones (lushi) are the name for engraved stelae often bearing distinctive deer motifs which have been found at Eurasian steppe sites dating from the 13th to the 7th and 6th centuries BCE. More than 80 have been found in Ili prefecture. (See Fig. 3) They have been found either standing alone or arranged in groups at burial grounds or sacrificial sites. In addition to deer motifs, they are also carved with images of cattle, horses, goats, pigs, donkeys and fantastic beasts. Others are engraved with circles or linked dots, thought to represent ear ornaments and necklaces, as well as other items of apparel and weapons.

Fig. 7 Open-work bronze plate on stand with human figures and sheep, Saka period, unearthed in Narat, Xinyuan county, in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

The bronze age of the region is termed the Agarsrsheng type of the closely related Andronovo found in Kazakhstan. The Ili bronze age is dated from 2000 BCE to the 8th or 7th centuries BCE. A number of ancient mines and smelters have been excavated in the area, making it clear that copper was locally mined and worked. (See Fig. 4) The Nurasai copper mine, located south of the Kax River and 3km south of Nilka, is the best preserved and the earliest mine in the whole of Xinjiang. Ten vertical ancient shafts have been identified.

Fig. 8 Gold cup with tiger-shaped handle and inlaid with agates dated to period contemporary with the Southern and Northern Dynasties, unearthed at Boma ancient cemetery, Zhaosu county, in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

From the 8th century BCE onwards, the activities of nomadic bronze cultures in the region are evidenced by the archaeological record. These people are believed to have been the people called the Saka in ancient Persian histories, Saca or Saga by Graeco-Roman writers and Sai in the Chinese dynastic history Han shu. A bronze statue of a Saka warrior unearthed at Gongliu (Fig. 5) is similar to another bronze figure in the collection of the Xinjiang Regional Museum in Urumqi. The kneeling figure of the Saka warrior in the latter museum suggests that the Saka wore pointed felt hats, loose garments and long felt boots. The Saka bronze culture seems to share affinities with other northern bronze cultures of the Eurasian steppe. Very typical is a bronze cauldron unearthed in Zhaosu county. (See Fig. 6) More unusual is a tripod stand of bronze, the surface of which is decorated with human and sheep designs. The legs supporting the stand are hollow. (See Fig. 7) Another distinctive Saka rectangular bronze tray with human mask and beast-shaped legs was unearthed at the Qiongbola site, also in Xinyuan county.

Fig. 9 Gold pot unearthed at Boma ancient cemetery, Zhaosu county, in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

A number of earth mound tombs have been excavated in Nilka county. In the 2001-2004 excavations at Jiligtay reservoir, more than 700 tombs were identified. Some of the earth mounds were surrounded by stones. Burial accessories included pottery, some of it painted, timber, stone, iron, leather and bone items, as well as the bones of animals. Much of this material is still being examined in the laboratories of the museum, but contemporary material from the Jialegesikayink, Qiongkek and Akbuzaogou sites is on display.

Fig. 10 Gold mask unearthed at Boma ancient cemetery, Zhaosu county, in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

The Wusun people are the next nomadic polity to be identified in the displays at the Ili Kazak Museum. The Wusun are described in the explanatory material provided in the museum as "a branch of the Turkic people who first inhabited the Gansu Corridor", and who moved westwards into the Ili river valley in the 2nd century BCE. The Wusun are said to have had a population exceeding 125,000 households, according to a section of the Han shu, titled Wusun zhuan. There are thousands of tombs of the Wusun scattered over the Ili steppe. Since 1961, excavations of these tombs have been conducted at a number of sites. Many of the tombs have a burial chamber made of logs joined together with mortise and tenon, with felt blankets hanging on the walls, so that the chamber resembled a log cabin of the type in which the Wusun lived.

Fig. 11 Yuan blue-and-white pot unearthed at Yuan dynasty site in Beijing, and very similar to a piece in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

After a period of chaos, unity was established over the steppe by the ancient Turks who at the height of their power in the 6th century, commanded a sweep of territory from Liaodong in the east to the Caspian Sea in the west, and from the Oxus River in the south to Lake Bailkal in the north. This empire provided a foretaste of the Mongol empire to come. From the 6th to the 12th century, communication routes forming part of the Silk Road network ran through the Ili region. In 1997, archaeologists working in Zhaosu at the Boma site, where three large tombs covered with earth mounds had been discovered, uncovered a hoard of items belonging to this period and testifying to the wealth flowing from the Silk Road. In one tomb believed to have been that of a Western Turk king of the late 6th century a trove of silk fabrics and gold objects was uncovered. Several of these objects are now on display in the museum. Notable is a gold cup, measuring 16cm in height, which has a tiger-shaped handle and is encrusted with agates set in diamond-shaped lozenges. (See Fig. 8) Also discovered was a gold ring featuring roe pattern beadwork and set with a ruby, as was a 17.2cm high gilded silver pot with a single handle. A lidded gold jar featuring inlaid rubies and standing 14cm in height was also discovered. (See Fig. 9) This piece weighs 489g. The discovery in the tomb of what might be a mask of the tomb occupant was also unearthed. (See Fig. 10) Measuring 17cm in height and 16.5cm across, the eyes on this mask of a bearded king are set with rubies.

Fig. 12 Stone plaque with Nestorian cross, Yuan dynasty, unearthed at the Alimali site, Huocheng county, in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

The Alimali area of Ili prefecture gained in importance after the Mongol ascendancy and it was a major trading centre in this period. In May 1999, the Cultural Relics Management Office of Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture acquired a Yuan dynasty blue-and-white ewer (bianzhi hu ) with a phoenix-head spout and decorated with a phoenix and peony design believed to be made in Jingdezhen. Allegedly discovered by a farmer in his fields in Alimali in September the previous year, this vase is now on display in the museum. Only one other similar piece is known; it was found in 1970 at the site of the Yuan capital in Beijing and is now housed in the Capital Museum. (See Fig. 11) The find is said to demonstrate that the Jingdezhen kiln catered to the Islamic market, and that the trade route ran through the Ili region. Another item of the Yuan period on display in the museum is a stone plaque with a Nestorian cross unearthed at the Alimali site in what is today Huocheng county. (See Fig. 12)

Fig. 13 Cutaway diagram of Qazaq yurt, similar to a full-size example in the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

In the 1320s, Genghis Khan granted the territories he had conquered to his four sons. The Ili steppe subsequently came under the rule of Jaghatai and Ogodei. The territory of Jaghatai, his second son, extended from the Ili steppe to the Oxus River, southward to embrace the entire region west of Yanqi in the area of Xinjiang south of the Tianshan Mountains. Ogodei's territory was the territory of the former Naiman tribe east of Lake Balqash, including the Alta and Tacheng prefectures of Xinjiang and the western areas of Mongolia. During its strongest period the Jaghatai Khanate controlled the Ogodei Khanate, but in the 14th century the Jaghatai Khanate split into western and eastern khanates. The Western Jaghatai Khanante was centred in the Semirechye area of today's Kazakhstan, while the Eastern Jaghatai Khanate was centred in the areas of Xinjiang both north and south of the Tianshan mountains. In the latter half of the 17th century the Eastern Jaghatai Khanate was destroyed by the Jungar tribe from Mongolia. Objects of Jaghatai culture are also displayed in this section of the museum, which is brought to a close with material from the Qing dynasty. The Qing conquest of the region began with the suppression of the Jungars. The Qing display includes coins and objects from the Mansion of the Ili General, a post which, prior to 1884 was effectively that of Governor of Xinjiang. The Mansion of the Ili General in Alimali is currently being restored and it is possible that this material will be returned to the new site museum when that is completed.

Fig. 14 Qazaq saddle in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

Fig. 15 Qazaq wooden chest with bone inlay in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

The Ethnic Customs Exhibition at the Ili Kazak Museum focuses on the Qazaq (Kazak, Kazakh) ethnic group dominant in the prefecture. Like the Uyghurs, Qazaqs speak a Turkic language now written in China with the Arabic script. The Ili region is one of the areas where Qazaq ethnic identity took shape. This folkloric display is dominated by a large Qazaq yurt, the distinctive form of traditional housing. (See Fig. 13) The yurt is divided into two sections—one for living, and one for storage. The yurt is impressively decorated and seems extremely comfortable. The accoutrements of everyday Qazaq life fill the yurt, and around it are displayed traditional saddles, (Fig. 14) as well as items used for hunting, fishing and falconry.

Fig. 16 Qazaq butter churn in the collection of the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Yining.

Fig. 17 Exterior of the Xinjiang Regional Museum (now demolished).

Among the objects on display are a Qazaq wooden chest with bone inlay (fig. 15) and a butter churn. (See Fig. 16) The textiles and other objects acquired for the folkloric displays, either through donation or purchased, are not necessarily only Qazaq. They include an old Russian hat stand and a vintage sewing machine, as well as everyday items and utensils of many other ethnic groups. The display is only slightly diminished by a set of models standing inside the entrance dressed in national dress, none of them clothes made from original fabrics but rather tawdry satin replicas.

![Exterior of new Xinjiang Regional Museum (under construction), Urumqi. [BGD]](003/_pix/ili15.jpg)

Fig. 18 Exterior of new Xinjiang Regional Museum (under construction), Urumqi. [BGD]

As the 50th anniversary of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region approached in late August 2005, Xinjiang's capital, Urumqi, still lacked a regional museum. The former regional museum of the city (Fig. 17) had been inadequate for the display and preservation of the large collection of more than 32,000 items, but it was an excellent example of a bygone style of Soviet-style architecture which could well have served other purposes. The original museum opened in April 1953 and covered a total area of 52,000 sq m and the main exhibition floor had an area of 11,000 sq m.

Fig. 19 Painted pottery sarira reliquary of the Northern Dynasties period unearthed in 1975 in Keping county, Xinjiang, and originally in the collection of the Xinjiang Regional Museum.

However, the museum was demolished in 2002. This happened at the instigation of Du Gencheng, the man appointed director in 1995, to make way for a new grandiose structure. However, the new buildings are only now approaching completion. (See Fig. 18) Du Gencheng, the former museum's director, was sentenced in February 2004 to ten years' penal servitude, not for authorising the destruction of this rare example of the 1950s architectural heritage of Xinjiang, but for a number of crimes related to his position as director. He was originally investigated in 2003 for taking RMB 208,000 yuan in bribes related to contract work for air conditioning and other aspects of building work at the museum. It transpired that he had also been behind the theft of valuable items, including textiles, from the collection of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Museum. It is not known how many objects were either stolen or destroyed at Du's instigation, but, according to one former colleague, he ran the museum like a "free market with dealers coming and going as they pleased".

![P20 Sign indicating location of interim displays of mummies at site of Xinjiang Regional Museum (under construction), Urumqi. [BGD]](003/_pix/ili16.jpg)

Fig. 20 Sign indicating location of interim displays of mummies at site of Xinjiang Regional Museum (under construction), Urumqi. [BGD]

Fig. 21 Sheep's wool felt rug measuring 76 cm x 74 cm of the Han dynasty unearthed in 1983 at the Shanpula cemetery site in Lop county and now in the collection of the Xinjiang Regional Museum, Urumqi.

Some of the details of his organisation of break-ins and thefts have been published. In 2000, Korla police produced evidence that a dealer by the name of Arim Maimaiti sold 22 precious woollen fabrics, excavated at the 2,000 year old Shanpula and Zaghanluq sites, from the museum's collection to an antiques smuggling ring. Arim Maimaiti was a close associate of Du Gencheng. In September 2002, six precious objects from the Loulan and Niya sites were stolen during another break-in. Even state-level Class 1 cultural relics went missing from the collection including a painted pottery sarira cask. (See Fig. 19) This rare item, dated to the Northern Dynasties period, was unearthed in 1975 at a Buddhist temple site in Keping county, Xinjiang. It stands 17.5cm in height and has a close fitting lid at the tip of its cone. The object is well known and published, and can only now have disappeared from sight into a private collection, if it has not been destroyed. Alarmingly, Du Gencheng's modus operandi also included filing reports detailing the destruction of objects as a result of mould or damp. In 1997, he reported the destruction of 80 items of Qazaq, Mongol and Xibe folkloric material, and in 1998 of a further 20 items of similar material. Apart from gross mismanagement, corruption, vandalism, theft and conspiracy, Du Gencheng is also believed to have taken massive bribes for authorising illegal excavations at sites throughout Xinjiang, including Niya and Loulan, by Chinese and foreign dealers.

Fig. 22 Top section of pottery drinking vessel of Tang dynasty period unearthed in 1976 at Yotkand site, Hotan (Khotan) and now in the collection of the Xinjiang Regional Museum, Urumqi.

The Xinjiang Museum had an internationally-renowned collection, but visitors have been appalled by the exhibition of ancient mummies that now stands in for a museum on the original grounds. (See Fig. 20) It is clear that another charge that could have been laid against the defunct director is that of neglect and mismanagement.

The new museum will hopefully be completed in time for the 50th anniversary of Xinjiang's establishment. Will the Museum still house one of the world's oldest carpets—a two thousand year old sheep's wool felt rug (Fig. 21) unearthed at the Shanpula cemetery in 1983? Or the Tang dynasty pottery cup (Fig. 22) unearthed near Khotan in 1976? A new system for appointing museum directors is being introduced at the beginning of 2006, in large measure to ensure that someone of the calibre of Du Gencheng is never again allowed to manage a major museum. [BGD]

|