|

ARTICLES

Enfant du Siècle: The Urban Symphonies of Zhang Ruogu | China Heritage Quarterly

Enfant du Siècle: The Urban Symphonies of Zhang Ruogu

Jonathan Hutt

Urban Symphony: Shanghai and Jung Wien

I thoroughly detest Shanghai's mercantile society. It is no longer a village but, as yet, it is still not a true city. It hesitates at the crossroads, possessing neither the beauty of the countryside nor the élan of a metropolis. Consequently, only its ugliness is visible.

—Gao Changqiao 高長虹 'From Shanghai to Berlin' (1926)[1]

No one could have disagreed more vehemently with the sentiments expressed by Gao Changqiao than the young Shanghai littérateur Zhang Ruogu (1905-1960), a man who would devote much of his career to disproving similar claims made by members of an increasingly vocal anti-Shanghai intellectual cabal. If, as Gao argued, Shanghai was indeed a city in transition, then, for Zhang, it was one of extraordinary promise; for it was the descendant of the great European capitals from antiquity to the present day, a progeny that could well bring the ideals of these ancient and alien civilizations to the Far East and into the modern age. By the dawn of the Nanjing decade, Shanghai had reached a pivotal moment in its short but far from illustrious history, and now the city stood at the threshold of a new age, one when it might finally take its rightful place alongside the greatest civic and artistic capitals in world history.

Fig 1 From Boy of the Chinese City to Man of the World. Zhang Ruogu: Author, Critic and Shanghai's leading Aesthete.

This extravagant claim alone would make Zhang Ruogu, author and critic, the most impassioned and loyal advocate of a new Shanghai. Furthermore, by entwining his city with mankind's greatest achievements, Zhang also displayed grandiose personal and professional ambitions. Like his mentors within Shanghai's Occidentalist and Francophile salons, Zhang firmly believed that by turning his life into a unified piece of art, he was anticipating the birth of a new artistic civilization that would eventually transform not just the city but also the nation. Consequently, the works of this prolific man of letters were designed to instil in both the connoisseur and the crowd a sense of civic pride that would banish, once and for all, the negative estimations of Shanghai and its residents. More than simply a guide to this new and often incomprehensible environment, Zhang's works were also meant to be an instruction manual on how to use this urban experience to remake oneself as the enlightened citizen of a future China.

Yet, even amongst the small yet zealous group of Shanghai's devotees, Zhang was unique; a man free from any trace of the ambivalence and self-loathing that underscored the writings of so many of his peers. As a result, Zhang bequeathed to future generations the portrait of a city that existed almost purely in the realm of the artist's imagination, a splendid chimera in which the artist and the city were joined by the cult of romantic imagery that came to be known as the Shanghai Style. The foremost ambassador for the city and its intellectual ideals, Zhang's success in these endeavours rested upon both his untiring faith in his hometown and the fact that he himself was the very embodiment of the contradictory impulses that fuelled the city's metamorphosis. Born in the heart of the old Chinese city, Zhang would nonetheless become the most cosmopolitan of Shanghai's new authors, and his works would be amongst the most highbrow of his generation and a testament to his erudition, littered as they were with references to his European mentors in the realms of literature, music and art. An eccentric character and minor literary celebrity, Zhang was also an unapologetic supporter of the city's thriving yet much reviled literary and publishing worlds, a man who to his enemies seemingly embodied the many failings of the Shanghai author and whose fondness for romantic excess and juvenile role-play found expression in works that were both self-referential and self-reverential. Like the style of the city he was said to represent, Zhang would be reviled and ignored by many in his own time and expunged from all subsequent histories. Yet, even with the city's rehabilitation in the 1990s mentioned above, Zhang would frequently be subject to misinterpretation. Over time, he would become a figure inextricably tied to either rigid historical truths or the 'cultural imaginary' of the Republican literary élite. In actuality, Zhang's aspirations lived on the cusp of reality, tailored to accommodate life in the Nanjing decade, yet always foreshadowing the dawn of a long-awaited Belle Époque.[2]

Still, the model for Zhang's Belle Époque was never static, adapting itself to both his shifting tastes and the intellectual fashions of Republican China. With each new prototype Zhang added another dimension to his exotic world view, drawing upon places of which he had no first-hand experience and eras that had long since passed. In the process of seeking parallels between his own city and those European centres, which he believed epitomised the zenith of all cultural achievement, Zhang created more than a defensive wall around Shanghai, he created a vision of the metropolis that would belong not just to the city and the nation but also to the world. While few would dispute that Zhang was instrumental in lending intellectual credibility to the city's claim to be the Paris of the East, little scholarly attention is given to another unspecified though equally important influence on Zhang's writing. It is immediately apparent from his earliest works that Zhang's concept of Europe was initially vague and lacking any geographical specificity. Still, for Zhang, such boundaries were secondary to the notion of a broader empire united by common religion, culture and the language of music. Thus, it might be argued that the original muse of the precocious young author was not Paris but rather the capital of this great musical dominion, Vienna.

As the acknowledged birthplace of modern classical music, Vienna's credentials were beyond reproach. The city of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, it had given birth to the classical symphony and the string quartet, along with great masterpieces of religious and choral music. Yet, the city's golden age would outlive these immortals, enjoying a second period of glory that differed radically from its first incandescence. As Peter Hall has noted, this next phase was characterised by more than striking changes in music, it signalled the dawn of new movements in the fields of literature, philosophy, social sciences, and the visual arts. Jung Wien, as it came to be known, was a point of convergence for the avant-garde and home to such illustrious figures as Mahler, Schoenberg, Freud, Schnitzler, Kraus, von Hofmannstahl, Wittgenstein, Otto Wagner, Loos, Klimt, and Kokoscha.[3]

Like Shanghai, Vienna was also a city of conflict and contradictions, one that seemingly straddled the worlds of tradition and modernity. The centre of the once mighty Hapsburg dynasty, by the late nineteenth century it was the symbol, and centre, of an empire in decline, characterised by the decadence of its inhabitants and their pursuit of all that was frivolous and immoral. It was this very corruption that helped transform a city once known as the epitome of artistic orthodoxy into a centre of radical new intellectual trends and artistic movements that signalled the birth not only of the modern world but also the modern mind. If there was much in the Viennese paradigm to attract the Shanghai intellectual, there were still more concrete parallels between the two cities. In their heyday, both Shanghai and Vienna were considered gateways to other realms, the meeting points of different cultures and a magnet for great talent and economic migrants alike. Both had been transformed by population explosions, generating phenomenal wealth and abject poverty, and a new middle class élite, who would help determine the shape of a new urban culture. Moreover, their residents had created public spheres and modes of living that fascinated outsiders, a world of entertainment, extravagance, and epicurean tastes.

Though largely unrecognised, the Viennese influence would be visible in all Zhang's shifting literary and intellectual personae; the author of delicate feuilletons who appreciated the perfection of Brahms second symphony, the Neo-Classicist who upheld the Hellenic ideal, the romantic Francophile who chronicled the birth of both the literary salon and fresh urban playgrounds, and the new intellectual-aesthete who championed the literary experimentation of his peers. The common thread that bound these disparate personalities together was their musicality. All would attempt to capture in prose the ephemeral cadence of this city, a euphonic air that was variously exhilarating, haunting, and even tragic. Be it his fiction, criticism, or translations, each would become a new movement in Zhang's majestic urban symphony.

While the enormity of Zhang's undertaking was unique, his passion for music and his belief in its educational power was hardly exclusive. As Heinrich Freuhauf's groundbreaking study of urban exoticism in modern Chinese literature illustrates, for many Republican intellectuals music was 'the most synesthetic and most directly effectual medium of the arts.'[4] Nor is it surprising that some of Zhang's closest colleagues were at the forefront of the intellectual endeavours to foster musical appreciation amongst the Chinese people. Significantly, it was shared musical tastes that initially brought Zhang into contact with two figures who as patrons would help launch his fledgling literary and social careers, publishing his works, providing prefaces to his earliest collections, and introducing him to members of the city's smartest literary sets. Xu Weinan, whose translation of the Romain Rolland biography of Beethoven was certainly compulsory reading for the graduate of Shanghai prestigious Université L'Aurore (晨丹大學), would co-opt Zhang for his most ambitious publishing venture. This was the multi- volume encyclopaedia of Western aesthetics, the ABC Compendium (ABC 叢書).[5] Perhaps more importantly, he would also provide Zhang with entrée into the hallowed realm of the Francophile salon, where the aspiring author would encounter the greatest influence on his literary career. However, it was Fu Yanchang, a man who might rightly be considered the Walter Pater of Republican China, who moulded the still nebulous thoughts of a young man whose love of music was equalled only by his devotion to the Church of Rome and the masterpieces of European literature.

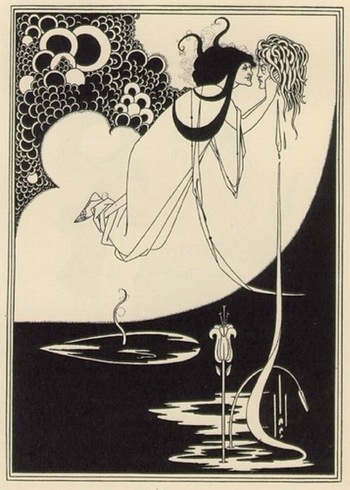

Fig.2 The Attic Spirit comes to China: Zhu Yingpeng's 'Aglow'

The godfather of the city's modern intellectual salon, the foremost authority on the Attic spirit, publisher, promoter, and a critic remembered as much for his dandified appearance as his robust prose, Fu was also editor of the landmark journal, Music World (音樂界). Here, Fu set about introducing the reading public to the great Western composers and their works, virtuoso musicians, and various musical forms from sonatas and arias to canticles and pastorals. So impressed was Fu by this young prodigy, that in compiling the magnum opus of the Occidentalist school, Three Personal Views on Art, Zhang musings on the such diverse music-related topics as 'Chamber Music and Solo Recitals' (室内樂與獨秦樂), 'Faust' (歌劇浮士德), 'Categories of Jiangnan Folk Music' (江南民歌的分類) and 'The Musical Forms of Opera' (歌劇的樂式) covered almost two hundred pages. It was also under Fu's tutelage that Zhang was encouraged to publish his 1927 collection, Let's Go to the Concert. Yet, still very much the apprentice, Zhang, whose works were alternatively didactic and impressionistic, had trouble giving voice to his personal aesthetic. Accordingly, Zhang quoted extensively from the works of his contemporaries, including Wang Guangqi (王光祈), a leading light in the Young China Association then studying music theory in Berlin and author of An Analysis of Musical Systems East and West (東西樂制之研究).[6] However, it was left to Fu, who had already devised an aesthetic blueprint for the city and the nation, to provide a theoretical framework for his acolyte's work.

Arguably, Fu was the first Chinese intellectual of the modern age to argue that a thriving musical world was an essential part of the cultural infrastructure necessary for any Chinese Enlightenment.[7] In his preface to Zhang's Let's Go to the Concert he acknowledges the great progress made towards realizing this dream, citing larger audience numbers at concerts and a greater musical appreciation amongst concert-goers. Since his own musical epiphany in 1915 when the author witnessed an Italian opera troupe perform Othello, Carmen, and Faust, Shanghai's residents could now enjoy a full concert season from October to May, performances by visiting foreign musicians, opera companies and dance troupes, and music in the home courtesy of new technical advances such as the radio and gramophone. Yet, misconceptions of this vital art form still prevailed. The contemporary Chinese music lover often failed to grasp the power of music to transform society. Confusing 'serious' music with the popular musical genre, they considered it to be an essentially feminine pastime and believed that a rudimentary knowledge of the foxtrot and the waltz was sufficient for the modern city-dweller. For Fu, quite the reverse was true. Not only was music the expression of the heroic and deeply artistic spirit that gave rise to great civilizations, it was the driving force behind the warrior races who, unafraid of death, had gone on to conquer the world. More alarming still, were the nation's music enthusiasts who appreciated the art form merely on a technical and not an emotional level, and with no regard for its place within mankind's artistic heritage. Like all Fu's writings, his remedy for such ills was largely impracticable, and he called upon the Chinese citizenry not only to engage in a rigorous study of Western musical theory, but also to imbibe regularly the heady atmosphere of the concert hall, preferably in Europe.[8]

If the young author at times appeared to simply regurgitate Fu's aesthetics of musical appreciation, his true contribution to the Occidentalist body of work was more significant. Zhang's early works were unique in that they offered a guide to concert hall etiquette as well as instructions as to the correct emotional response to various musical forms. Yet, in doing so Zhang was also inculcating in the concert-goer the notion that members of the audience were more than simply passive spectators, they were active participants in the performance itself, a concept of vital importance to the Occidentalist coterie for whom,

Music was…a three dimensional spectacle in which musicians and audience alike participated. At the concert hall, the Shanghai journalist could observe foreign diplomats drinking champagne, ladies in gala dresses, perfect manners, smooth lighting, ornate architecture, sumptuously printed evening programs, and the euphonious 'revolutions' described by the music of Beethoven or Schubert. It was the sanctuary where the foreign residents of Shanghai were affirming their civilization in its most sacred ritual. [9]

Perhaps unwittingly, Shanghai's Occidentalists were seeking to replicate the Viennese experience. In his memoirs, Stefan Zweig recalled the spirit of fin de siècle Vienna when the city's residents and its flourishing theatrical world appeared to have attained a state of perfect harmony.

It was the microcosm that mirrored the macrocosm, the brightly coloured reflection in which the city saw itself, the only true cortigano of good taste. In the court actor the spectator saw an excellent example of how one ought to dress, how to walk into a room, how to converse, which words one might employ as a man of good taste and which to avoid.[10]

It was this very synchronicity between art and the city that Zhang would attempt to capture in prose. While contemporary scholarship depicts the musicality of Zhang's prose as simply a literary device employed by many of his generation to capture the rhythms and sensations of modern urban life, it is more accurate to consider literature as merely the medium through which Zhang might convey how music was the distillation of all human experience. Yet, in order to give expression to this philosophy, the author would first have to find his literary voice and, more importantly, refine his own relationship with the city, a process which when complete would give birth to two of the most important literary works in the city's history: the aptly-titled fictional work, Urban Symphonies and the collection of essays, Exotic Atmospheres.

Zhang's musical and literary worlds would coalesce in his 1929 essay, 'The Dōbun Academy's Autumn Recital' (Tongwen qiujie yinyuehui 同文秋節音樂會).[11] This work starts with an account of Zhang's sense of ennui brought on by the inclement weather; days of persistent light rain that have confined him and his neighbours to their cold rooms. However, with the dawn of a clear day, Zhang is finally able to throw off this emotional paralysis and venture outside. Making his way to North Sichuan Road 北四川路, he discovers an advertisement for an upcoming recital in the window of a store selling musical instruments. Learning from the store's manager that the concert by students of the Dōbun Academy will take place on the evening of the 11th at a club for Japanese expatriates, the author promptly purchases a ticket. The lion's share of this essay is devoted to recording his impressions of the concert itself. This detailed account includes everything from observations on the orchestration and the melodic structure of certain works to the attire and even the stage fright of the performers. As the performers are merely students, Zhang does not hesitate in offering constructive criticism. He points out the almost whimsical nature of some pieces that pale in comparison to more orthodox works. He lauds the use of Eastern colour in an orchestral work by the Japanese composer, Saitō Fujiō 斎藤勝, but adds despite being conducted by a man of obvious talent, the absence of any internal harmonic development means that this piece lacks emotional depth. There is also the uneven performance of a young pianist who, while technically adept, cannot maintain the emotive power of the work. Still, there is much worthy of praise, in particular the diminuendo of a choral work, which, for Zhang, epitomises classical elegance.

At first glance, this essay is an awkward amalgam of Zhang's traditional musical criticism and the style of confessional literature in which he now specialised. Yet, while it is neither a masterpiece in terms of either literary creation or musical criticism, its true success lies in the fact that it records the many facets of this spectacle, the symbiotic relationship that exists between the musicians and the spectator, the concert hall and the urban setting, and the artist and art.[12] Consequently, Zhang's journey through the city is also a spiritual voyage from ennui to exhilaration. The author employs seemingly incidental details to chart his progress, from the chill of the artist's 'garret' to the damp pavements of North Sichuan Road, to the music store, a refuge from the chaos of urban life, and finally the cultured environs of the auditorium itself. The characters encountered by the narrator also contribute to the ambience, specifically the courteous manners of the store's proprietor and the predominantly Japanese audience elegantly attired in both traditional and Western dress, all of whom anticipate the refinement of the music by Beethoven and Bach.

It is this very atmosphere that Zhang takes with him on his departure, one which the artist finds mirrored in everyday urban life. Like Zweig, Zhang sees the concert as the reflection of the urban experience, encapsulating the various emotions and themes which together define human existence. Yet, unlike the Viennese of the Belle Époque, Shanghai's residents were not attuned to the rhythms of their city, unconscious of the various cultural experiences that made up the artistic civilization of the polis. Therefore, by depicting the musical atmosphere of the city, Zhang hopes to awaken his readers to the fact that by simply participating in the life of the city they are sowing the seeds for their own enlightenment. Here, Zhang echoes not only the Occidentalist manifesto of 'art for life's sake' but the artistic credo of Jung Wien. Like Otto Wagner before him, Zhang endeavours to recreate the world, offering the formula not for a renaissance but rather a 'naissance, a completely new beginning.'[13]

In many regards, Zhang's career can be said to have followed the trajectory of nineteenth century Vienna, combining the musical perfection of the late Baroque and early Romantics with the exciting and frequently shocking experiments in aesthetic modernity that typified the city's avant-garde. From his earliest attempts at musical criticism, Zhang would discover the musicality of the city, which in turn would come to define his own sense of literary mission. Henceforth, Zhang's role as an artist would be inextricably linked to the city of his birth. It was the beginning of a voyage in which he would explore his environment, a journey during which he would discover new aspects of city life and new models upon which to base his unique urban vision. Shunning the natural wonders of Scandinavia, and even the classical ruins of Rome, Zhang now identified the great musical centres of Vienna, Berlin, Paris and London as the focal points for his cultural peregrinations both real and imaginary.[14] Moreover, this would also be a voyage into the recesses of the artist's imagination. Here he would become the painter of modern life, whose sole ambition was to capture the beauty of this illusory world.

Sacred and Profane: A New Urban Vision

There then is the delightful spot where I was born in sin, the air from which I breathed poisoned perfumes, the sea of pleasure upon which I heard the Sirens sing! There is my cradle according to the flesh, there my home according to the world! A cradle of flowers and a home of nobility in the eyes of men! It is natural, Alexandria, for children to cherish you as a mother, and I was reared upon your breasts decked in magnificence. But the ascetic despises nature, the mystic disdains appearances, the Christian regards his human home as a place of exile, and the monk shuns the world. I have turned away my heart from love for you, Alexandria. I hate you! I hate you for your wealth, for your science, for your gentleness and for your beauty. My curse be upon you, temple of demons.

—Anatole France Thaïs (1890)[15]

Zhang's use of a lengthy quote from Anatole France in his most dogged defence of his beloved Shanghai would have surprised neither his detractors nor his admirers. For Zhang and many of his closest acquaintances, France, who had passed away only a few years earlier in 1924, was both one of the literary immortals and the consummate French stylist, an author renowned as much for his erudition and love of beauty as his graceful prose. Zhang's very public adulation of and identification with France had reached its apex in 1928 with the publication of his La Vie Littéraire (文學生活), an homage to the four volume collection of causeries published by his idol in the final decades of the nineteenth century. However, Zhang's borrowing from the Nobel laureate was more than simply another example of literary name-dropping. Written at the height of the Shanghai intellectuals' fascination with French literature, the words of France added weight to the highly contentious argument Zhang set forth in this essay, entitled 'The Seductive Metropolis' (都會的誘感).[16] Such measures were prudent as not only did Zhang's line of reasoning run directly counter to conventional opinions of Shanghai, it was also a contemptuous critique of the city's enemies by a man better known for his enthusiastic praise of his contemporaries and the European artistic canon. As its title suggests, here Zhang offered an entirely new vision of the metropolis, which, while deeply indebted to the thinking of the Occidentalist élite, was also radical in its interpretation of the city's splendours. Consequently, 'The Seductive Metropolis' can be said to represent a unique moment in the city's intellectual history when polar conceptions of Shanghai converged, a continuation of the Occidentalist dogma and an anticipation of a modernist dystopia that was then forming in the imagination of a new generation of Shanghai writer. The synthesis of the classical and the modern, the sacred and the profane, Zhang had found a way for the city's authors to resolve many of the contradictions that lay at the heart of the Shanghai Style. Yet, ultimately Zhang's philosophy failed to sway his colleagues, eclipsed as it was by the growing chorus of anti-urban sentiment and rejected by the city's former supporters who quickly capitulated to demands for intellectual and political conformity.

Ostensibly, this essay might well have been penned by any member of Shanghai's Occidentalist salon. As in their earliest works, the city is once again praised as the pinnacle of mankind's achievements where the civic ideals of Ancient Greece have continued into the modern age. Quoting Fu Yanchang, Zhang equates Europe's most modern cities with the realisation of their artistic vision, where purely material phenomena, be it monumental architecture, beautiful mansions, or the pristine tree-lined streets, take on great symbolic significance, both a mirror of man's primal instincts and monuments to his subjugation of nature. Still, the author's acknowledgement that he was merely reiterating long-held beliefs is in itself highly important for it illustrates that, despite the famed fickleness of the Shanghai intellectual, the Occidentalists had not jettisoned their beliefs in order to keep abreast of intellectual fashions. In fact, if anything, the Occidentalists' philosophy had finally garnered some degree of mainstream acceptance. Finding themselves suddenly in vogue, the Occidentalists became still more prolific, launching a new periodical in which they might continue their Attic-inspired educational campaign. Eliciting contributions from writers of all intellectual and ideological persuasions, Athens (雅典a title that suggested classical elegance) was launched in 1929, offering its readers an insight into both the ancient and modern worlds. While much space was devoted to examining all that came under the orbit of classicism from Homer and Michelangelo, this journal also featured the latest developments in the worlds of literature and visual arts, both domestic and foreign. Such was the increased currency of the Occidentalist ideology that it now spawned a series of similar publications, including Apollo (雅波羅) and Aesthetic Education (美育).[17]

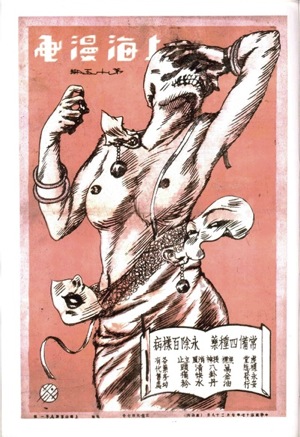

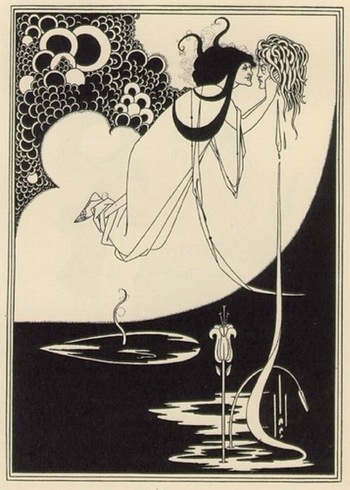

Fig.3 Inspiration for a generation. Aubrey Beardsley, Illustration for Oscar Wilde's Salomé

While the Occidentalist clique remained true to their ideals, they had also fine-tuned their thinking to account for a fresh view of the classical world that owed much to the decadent movement of fin de siècle Europe. Though a highly contentious label, many of the city's most prominent authors dabbled with decadence, from Ye Lingfeng (葉靈風), whose works featured his own Aubrey Beardsley-inspired illustrations, to the sculptor and self-confessed symbolist poet, Li Jinfa, whose poetry recorded the sufferings of la juenesse dérancinée and whose very nom de plume, Jinfa or 'golden haired', suggested a head of luxurious Apollonian curls.[18] The Republican fascination with decadence extended beyond the literary world to the visual arts, where artists such as Ye Qianyu (葉淺予) developed themes of the femme fatale and 'the terribilatà of dying civilizations' as major motifs in their depiction of Shanghai's corruption.[19] However, without doubt, the true poster boy of Chinese decadence was Shao Xunmei (see Hutt's piece on Shao Xunmei in the June 2010 issue), whose poetic début featured odes to both Sappho and Swinburne, and an epic poem on the fall of man.

Ah, this withered paradise,

A burial ground for what strange beauty?

God!

You have locked within all enticements,

All desires forever debarred.

God! [20]

With his passion for French literature, it was Zhang Ruogu, however, who played a key role in bringing the Occidentalists' frequently jaundiced view of antiquity into line with the current artistic tastes. Although more colourful literary characters competed for the mantle of China's greatest decadent, it can be argued that it was Zhang himself who represented the true spirit of a Chinese decadence. Such tendencies were evident even in Zhang's earliest writings, specifically in his outright rejection of the natural world in favour of the artificial urban landscape.[21] Still, it was only when he sought to capture the essence of his hometown that Zhang exposed, albeit unconsciously, the decadent undertones of his world-view. In his impressionistic sketches of Shanghai that accompanied 'The Seductive Metropolis,' Zhang offers the reader entrée into the realm of artifice, an exploration of the imagination where experience and the pursuit of experience were ends unto themselves. While many of his generation championed the credo of 'art for art's sake' and indulged in similar fantasies of cosmopolitan Shanghai, none could match Zhang's unique sensibility, a mental landscape where all boundaries remained blurred, allowing Shanghai's exotic niches to segue seamlessly into Athens, Alexandria, Paris, or Berlin.

If his colleagues' understanding of decadence was largely cerebral, then as a devout Catholic, Zhang's comprehension possessed a decidedly more numinous aspect. It was the notions of blasphemy and sin absent from the work of his peers that informed the arguments set forth in 'The Seductive Metropolis.' To the Occidentalists' city of enlightenment, Zhang now grafted the city of earthly pleasures, creating an unusual hybrid that, for the author, explained the very inconsistencies at the root of the modern condition. By his own admission, Zhang's conception of Shanghai's many temptations was entirely foreign. Professing a profound ignorance of classical Chinese literature (a fact in which he took great delight), Zhang's thesis relied upon the works of such great European writers as Gustave Flaubert and Anatole France. If Zhang's references to the Lord's Prayer attest to his religious convictions, then Flaubert's kaleidoscopic La Tentation de Saint-Antoine and France's sensual evocation of pagan Alexandria provided him with the rich hues with which to depict the charms of Shanghai. For Zhang, there was a direct correlation between the Temple of Serapis, the magnificent villas steeped in perfume, and exquisite brass statues housed in marbled vestibules and the splendours of 'East Asia's sole metropolis,' an array of peculiar and dazzling sights, which in the word's of Zhang's close friend, Ni Yide (倪貽德), 'hypnotize like a seductive demon.'[22] Zhang's catalogue of temptations would embrace all facets of the city's great material civilization; a world of machinery and perpetual motion, sumptuous satins and silks draped on the bodies of elderly matrons and prostitutes alike, the refinement of the art gallery and the more primal sensations of the dance hall heavy with the scent of wine, smoke and flesh.

Since the Occidentalists considered the city to be the centre of modern life and the source of all new movements in the arts, then the myriad temptations of the metropolis must also be an essential aspect of both the urban lifestyle and the artistic experience. Therefore, in spite his own religious beliefs, Zhang now declared that is was incumbent on the modern artist to submit to the 'decadence of this floating life.'[23] Yet, such temptations were purely an intellectual pleasure and as such did not require the artist to physically engage with the putrescence and decay of modern life itself. Instead, like Joris-Karl Huysman before him, the artist's very 'corruption' became a means by which he might define his own opposition to conventional morality as they applied to society and the arts.[24] The standard bearers of such norms in China were the champions of moral and aesthetic traditions, whom Zhang, in keeping with the European flavour of his prose, now dubbed the Parnassian movement (高蹈派). Zhang ridiculed the rustic ideal of those city-based intellectuals who resided in Shanghai and enjoyed the fruits of city living, but constantly bemoaned their alienation from nature. To Zhang, their loud and bitter denunciations of this 'haven of a myriad evils' and the 'den of degenerates' were little more than symptomatic of their intellectual and artistic redundancy.

Clearly, Zhang's aestheticism was peculiar to both the era and his environment. Like many of his peers, Zhang's decadent motives were evidence of his susceptibility to the intellectual fashions of Republican Shanghai during the Nanjing Era. However, if Zhang's decadence was a stylistic device that helped add colour to his prose, it was also an important intellectual tool which enabled the author to construct a new defence of Shanghai at a time when the city was increasingly considered to be in breach of May Fourth ideals. Consequently, though Zhang's prose style was indebted to the theory of l'art pour l'art, it would never be divorced from the Occidentalists' very ethical conception of their artistic mission. These noble professional and personal goals, which at times remained buried beneath Zhang's quasi-decadent persona, would find more concise expression in his essay 'The Stimulus of Spring' (刺激的春天).[25]

If Shanghai's temptations seemed firmly rooted in nineteenth-century European soil, its dynamism was grounded in the present day realities of treaty port life. Zhang's conception of Shanghai's charms was not only in direct opposition to current political thinking, it was also far broader than that of his Occidentalist peers. Outside the concert hall and far from the monumental architecture of the Bund, Zhang now found evidence of the city's splendour within the drudgery and oppression of the quotidian.

In our schools young men and women are worried and depressed by a plethora of physical and material concerns, while in society at large, the serving classes must struggle for even the necessities of life—for some, the simple question of putting food on the table engenders feelings of crisis, an unending quest for work, and many untold hardships. Thus, in their rare moments of leisure, people have come to believe that life is drab and flavourless.[26]

Far from being an indictment of contemporary society, Zhang's controversial essay, composed at a time when Marxism was gaining ascendancy in the intellectual world, considered social inequities to be the foundation of a new Chinese civilization. He predicted that from such adversity there would arise a new sensibility that would serve as the basis for all contemporary art, a condition with an exceptional European pedigree known as mal du siècle (世紀病). Recent history offered concrete evidence that the stress and anxieties of modern life and the concomitant desire of the artist and common man alike to find solace in absinthe and opium had spawned the marvels of modern European society and culture. Thus, European societies had now attained a state of perpetual spring, which despite its apparent privations was the season of growth and regeneration. Once more, Zhang asserted that Shanghai's ills might be harnessed to a greater creative good. By fostering this sense of isolation and deprivation, and by escaping into a world of sensation and experience, the city's residents might effect a personal transformation and become the harbingers of China's long-awaited cultural spring.[27]

Although the terminology of Zhang's aestheticism was entirely novel, the conviction that Shanghai was the key to China's enlightenment remained unchanged. What necessitated this new vocabulary was not shifting intellectual fashions but the radical changes within Shanghai society that in recent years had delivered neither a new Vienna nor a modern Athens as the Occidentalists had prophesised, but a culture of frivolity and vulgarity, while for others it allowed for politics and opportunism. As we have noted earlier, such developments had already alienated many Chinese intellectuals who regarded Shanghai's grotesque metamorphosis as a betrayal of their intellectual vision for a new China. None were more sensitive to such events than Shanghai's most ardent supporters, whose reputations were tied to the city's ability to realise their social vision. A unique and highly personal response to this dilemma, Zhang's objective in both these works was to reconcile the physical city with noble Occidentalist ideals. Accordingly, he now adorned their manifesto with the trappings of his current cultural preoccupations. Bringing together elements of high Romanticism, Classicism, and decadence, Zhang hoped to construct an impenetrable wall that might deflect the increasing number of barbs aimed not simply at the city but its intellectual élite. Yet, it was these very writings that would seal his fate. His apparent disdain for the sufferings of the common man, his artistic posturing, and his latently 'Sinophobic' comments would subsequently earn him the label of decadent.[28]

If, however, Zhang can be branded a decadent, the term is best applied not to his prose style but rather to the spirit of his work. While their agenda were radically different, Zhang's writings shared a singularity of purpose with Anatole Baju's journal Le Décadent for in both, 'the energies it sought to represent and advance, or those it sought to oppose, were far greater and more complex than its formulatory approach could hope to contain. Its pages were filled with proclamations, calls to order and that particular fusion of aggressive certainty and plaintive wishfulness which characterises so many soi-distant movements in thoughts and the arts.'[29] Furthermore, while the fascination with decadence that typified the early years of the Nanjing decade was only remotely related to the literary movements of France's Belle Époque and England's mauve decade, true to Matei Calinescu's theories on decadence their common sense of anguish and alienation were self-consciously modern and foreshadowed radical new developments in the cultural sphere.[30] This was certainly the case with Zhang, whose writings would serve as the link between two distinct phases in the thinking of the pro-Shanghai intellectual. Although he maintained the idealism of the May Fourth scholar, by embracing all aspects of the city's culture and, in particular, what its enemies considered the manifestations of Shanghai's vulgarity, Zhang anticipated a new breed of urban writer who would revel in the evils of city life and attempt to capture its unique sensibility, one that was founded upon similar feelings of anxiety and isolation. The temptations, stimulus and mal du siècle outlined in Zhang's works would quickly mature (or regress) into the aesthetic hedonism of Shanghai's most enduring modernists, the Neo-Sensualist school.

In addition to being a renewal of the Occidentalist manifesto, Zhang's writings were also a deeply personal response to the challenges presented by Shanghai's capricious transformation. The concept of mal du siècle upon which he had expounded would become more than merely a justification of the city's latest incarnation; it would be central to his own artistic mission and shifting intellectual persona. It moulded the author's belief that the citadel of art was a sanctuary into which the artist might withdraw and a means by which he might experience the minutiae of life in the manner of art. This discovery would prompt Zhang to explore his personal desires and succumb to the 'fantasy of [the] superlative emotional adventure'[31] that would ultimately find expression in his most extravagant work, Exotic Atmospheres. Signalling the triumph of imagination over reality, these visionary, dreamlike portraits of Shanghai would become the core of the city's new mythology. As a crucial aspect of the city's cultural ambience, the artist would feature prominently in these studies; but while Zhang's self-portraits took many different forms including those of the celebrity scholar, the painter of modern life, and the boulevardier, the background of these sketches increasingly resembled a city other than Shanghai. A zealous Francophile, Zhang's new model was the City of Light.

The City of Light and the doctrine of Exoticism

La vie parisienne est féconde en sujets poétiques et merveilleux. Le merveilleux nous enveloppe et nous abreuve comme l'atmosphere; mais nous ne le voyons pas.[32]

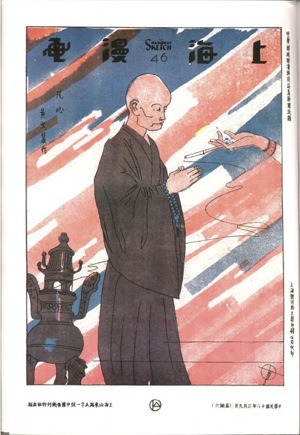

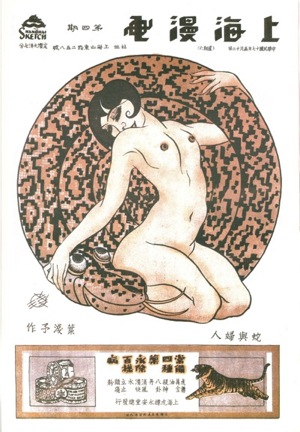

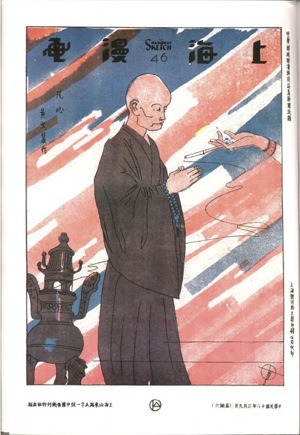

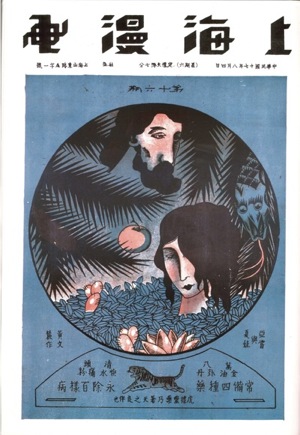

Fig.4 '..the delightful spot where I was born in sin..' Huang Wennong's's 'Worldly Pleasures'in Shanghai Sketch 9 March 1929

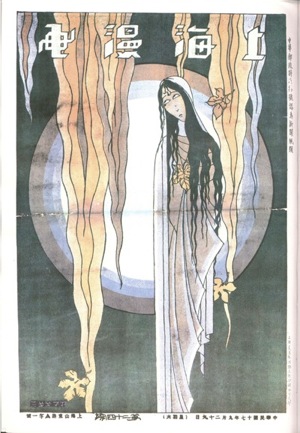

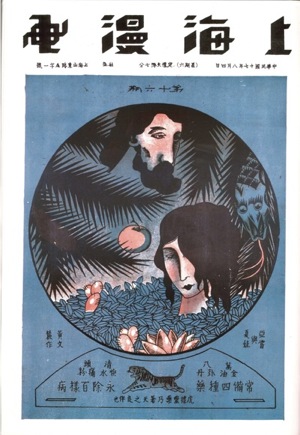

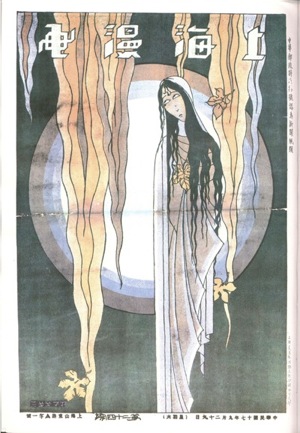

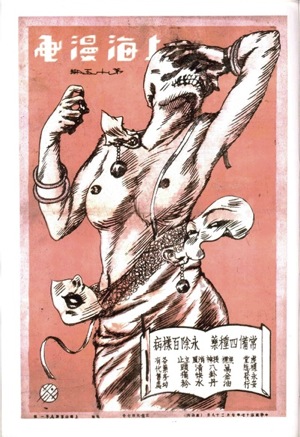

Fig.5 The Chinese Ophelia, Shanghai Sketch 29 September 1928

The publication in 1929 of Exotic Atmospheres was a personal and professional milestone for the twenty-three year-old author. Like many in Shanghai's highly competitive world of letters, Zhang had previously seemed content to collate his published writings on a single subject, an ethos that had already produced four books in just over three years including, Let's Go to the Concert, La Vie Littéraire, and Café Confabulations.[33] Despite this astonishing productivity, these homilies on the joys of the musical experience, the treasures of foreign literature, or the glamour of Shanghai's literary salon, were all motivated by a single desire: to attest to the centrality of Shanghai in China's social and cultural rejuvenation and to establish the city as the fons et origo of both modern art and the modern mind. To the reader familiar with the works of this young prodigy, it would have been instantly apparent that here Zhang was attempting something infinitely more complex. Though the content of this collection again featured the various styles of confessional literature in which he specialised, the citations of Shanghai's modern culture, translations of works by his literary heroes, and the effusive appreciation of his colleagues were now bound together by a new style of work that embodied a highly subjective and deeply personal configuration of the city. These impressionistic portraits of Shanghai recorded the author's experiences in the city's exotic corners and fragments of time in which the narrator appears to have transcended all geographical and temporal limitations. By committing these fleeting and ethereal atmospheres to paper, the author was endeavouring yet again to capture the beauty of modern life, a beauty peculiar to the urban landscape. However, for Zhang, this catalogue of sensations was also an evocation of the absolute. Like Charles Baudelaire, Zhang believed that the city's very ability to generate such transitory and ephemeral impressions validated his conviction that this city belonged to the great and universal, though decidedly Eurocentric, empire of Art.[34]

As the title of this work, Exotic Atmospheres, indicates, Zhang was not interested in depicting the sensibilities of traditional life, but rather the delicate atmospheres generated by physical monuments of the colonial presence.

Such sentiments might well have found favour with many of the Chinese literati who on their return from their studies overseas now congregated in Shanghai and sought to recreate the urbane existence they had witnessed, if not lived, whilst abroad. If in this regard, Zhang was typical of his generation; where he surpassed his contemporaries was in his ability to fashion a sketch of Shanghai that not only co-joined the city with the golden ages of alien civilisations both past and present, but one that blended the worlds of reality and that of the artist's imagination. Shanghai's exotic corners were more than simply a source of artistic inspiration, they were the very vibrations of la vie moderne which 'stimulate a specific part of our senses, which in turn transmit these impressions to the central nervous system, from where they oscillate through the entire body and even influence the abyss of our soul.'[36] For Zhang, the submersion of the self in these impressions would prove the most rich and rewarding experience of his career.

Clearly, Exotic Atmospheres was the author's most personal and emotional response to the city of his birth. It was also the work that would define Zhang's legacy. Again, like Baudelaire, Zhang had discovered within the city what he believed was the definitive spirit of the age, a timeless quality that might ensure the authenticity and durability of his art. Indeed the very sensations, desires, memories, and fantasies upon which these imaginary landscapes were built did, in a sense, prove ageless for they offered future generations a lexicon of images and emotions upon which to draw, and which would frequently resurface in both popular and scholarly writings on the metropolis. Ironically, just as Zhang had once relied upon the European canon to find a connection with another world, later authors would draw upon Zhang's esprit to build a bridge between the contemporary city and their idealised conceptions of 'Old Shanghai.' Therefore, while Zhang was by no means the first to draw parallels between China's 'Paris of the Orient' and the world beyond, his depictions of Shanghai's cosmopolitanism were unquestionably the most sophisticated and enduring of his era. However, Zhang was not merely seeking physical and cultural correspondence between Shanghai and the great European capitals, but the experiential, aesthetic, and deeply spiritual bonds that lay at the heart of his doctrine of exotisme.

It is possible that Zhang's notion of exoticism, or l'amour exotique, was simply the internalisation of the Occidentalist worldview. If the city was still defined as the cornerstone of modern society, it was also considered to be the repository of the individual creative spirit, a dominion where beauty might exist independently of ethical and humanistic concerns. Thus, Zhang's primary aspiration was to capture the essence of this city, which existed not only in the physical sphere, but also in the world of the spirit. In the lengthy prologue to Exotic Atmospheres, Zhang stated that the artist should aim to secure this moment of transcendence, when free from the confines of time and place, he existed purely in the realm of the senses. Still, the very 'moods, emotions, attachments, memories, desires and fantasies' that together formed the city's atmospheres were also in a state of perpetual flux, for they were the record of the shifting and contradictory emotions to which the residents of the metropolis were prey. Even so, amidst these unstable and formless airs, the artist might still discover the eternal, and by skilfully recording the sights, sounds, and perfumes of modern life capture the essence of the human spirit.[37] Consequently, within Zhang's doctrine of exoticism there existed a new relationship between the artist and the city. If such intangible impressions offered the artist the foundation of his art, then it was only through the artist's imagination that their import could be made known to the common man.

Considering himself merely the humble critic, Zhang was careful to distance Exotic Atmospheres from such exalted ambitions. Nevertheless, despite his modesty, Zhang was more successful than many of his contemporaries. While many of the extravagant claims made in these essays emphasise the author's naïveté, they are also testament to the purity of his fertile imagination. The triumph of the author's imagination is perhaps best seen in his essay 'A Quiet Moment at the Café Tichenko' (忒珈欽谷小座記) in which both the author and the city seemingly exist in a single moment, yet the reader is still invited to follow the author's musings across continents, cultures, and time. Like its companion pieces, 'The Dōbun Academy's Autumn Recital' and 'Local Colour Behind Paper Doors' (紙門里的風味),'A Quiet Moment at the Café Tichenko' is a work that, at first glance, simply chronicles another facet of the literary life, as armed with a copy of the Romantic's bible (Alfred de Musset's La Confession d'un enfant du siècle) the narrator finds refuge within the café's quiet elegance.

Sitting here is a truly pleasurable experience; the square tables with their exquisitely starched white tablecloths and small china vase containing two or three fresh and highly perfumed blossoms. In the highly polished silver cutlery one sees a faint reflection of the elegant young couple seated at the next table, while outside groups of smart urban youths stroll by, a daily occurrence as dusk begins to envelop the Avenue Joffre. In Shanghai, there is only this one narrow, tree-lined street where one may see so many genteel people from all parts of the globe, including French and Russian nationals and a considerable number of Chinese … . Here I am shielded from both traffic noise and rowdy street vendors, immune to the unpleasant odours that assault the senses. Within there is only the delicate whir of an electric fan and the sounds of silverware inadvertently grazing a porcelain cup, these sounds blending with the strains of a piano drifting down from the floor above. When there is nothing more along this street that can hold my attention, I return to de Musset's La Confession d'un enfant du siècle.[38]

What Zhang offers his readers here is more than simply a sketch of manners, a depiction of the new bourgeois lifestyle, or even a commentary on contemporary fashions; rather, he has created a unique portrait of the passing moment and in so doing casts himself in the new and exiting roles of artist, observer, and flâneur. An increasingly popular yet problematic term in contemporary scholarship, the flâneur of Republican Shanghai features as a central figure in two recent studies of the era. Yingjin Zhang has been keen to identify the flâneur in his review of new city narratives, in particular the works of the Neo-Sensualist school. He equates the flâneur with the voyeuristic central characters in the works of Mu Shiying and Liu Na'ou, the passant, who roams through this dark and erotically charged landscape encountering the grotesque human products of this moral vacuum, such as the femme fatale and her many victims.[39] Leo Ou-fan Lee, on the other hand, is more hesitant in applying the term to the works of Chinese modernists. Attempting to adopt Walter Benjamin's thesis, he argues that though the city is central to their works, these are the observations not of the anonymous spectator but of those immersed in and, at times, overwhelmed by the urban spectacle. Instead, Lee considers the pensive flâneur in the works of Mu Shiying closer to the figure of Pierrot, who conceals his despair beneath the mask of hedonism.[40] With his unbridled enthusiasm for the urban landscape, Zhang Ruogu hardly seems to match the profile of Baudelaire's critic of modernity. Nevertheless, the attitude that inspired Exotic Atmospheres is perhaps closer to the ideals of Baudelaire than that of his peers. Unlike the Neo-Sensualists' Chinese Gotham, which seems grounded in both reality and cliché, Zhang's landscape is merely a pathway into the realm of imagination.

And the external world is reborn upon his paper, natural and more than natural, beautiful and more than beautiful, strange and endowed with an impulsive life like the soul of its creator. The phantasmagoria has been distilled from nature. All the raw materials are put in order, ranged and harmonized, and undergo that forced idealization which is the result of a childlike perceptiveness—that is to say, a perceptiveness acute and magical by reason of its innocence.[41]

Zhang might well have seen himself reflected in Baudelaire's description of Constantin Guys' 'The Man in the Crowd.' He too considered himself the passionate spectator, at once engaged yet perpetually detached from the turmoil of la foule. He also shared with the flâneur an interest in all that was novel and even trivial, a trait, which even his critics must concede, had long been associated with the native Shanghainese.[42] Furthermore, for all his apparent sophistication, Zhang was the first to admit that his perception of the city was grounded in his lack of worldly wisdom. He readily informed his audience that such exotic fantasies were those of a man whose life was still very much entwined with the traditional way of life. It was precisely because he was a child of the Chinese city, who other than a quick visit to the new capital of Nanjing had never ventured far from the mudflats of Shanghai, that the exotic possessed such great allure for him. Consequently, his observations not only reveal what Klaus Schepe defines as the 'imaginative potential of urban experience' but also serve as the living embodiment of an ideal.[43] For Zhang, this ideal was now represented by the glamour and artistic splendour of la belle France. Accordingly, by interweaving these random images, Zhang creates more than simply an elegant backdrop for his personal fantasy; he invokes the hallowed artistic spirit of the City of Light. Shanghai's French quarter becomes an emissary of Haussmann's Paris, the Tichenko a replica of the fashionable cafés along the Parisian boulevards or the artists' cafés of Montmatre, while the great literary salons of the French capital are mirrored in Zhang's allusions to contemporary literary gossip and the repeated references to the work of de Musset.

From his earliest writings, it is clear that Zhang had long grappled with how to depict accurately the city's foreign ambience, be it the musical rhythms of modern life or the European feel of the city's cafés and its literary salons. If his doctrine of exoticism was the culmination of this intellectual and spiritual journey, it was a discovery made possible only by his encounter with a man of similar tastes and one whom, like Zhang, had only experienced the joys of Western culture indirectly, both on a cerebral and emotional level. This man was the celebrated author Zeng Pu. Zeng, whose popular and critically acclaimed novel Flowers in a Sinful Sea had secured his position amongst the literary élite, was now the figurehead of the city's Francophile salon and editor of the highly influential journal, Zhenmeishan (The True, the Beautiful and the Good). Despite the cut-throat nature of Shanghai's publishing world, this periodical enjoyed astonishing longevity. From its initial publication in November 1927 to its closure in July 1931, Zhenmeishan was instrumental in introducing the reading public to works of French literature, publishing translations of both major and minor works by such diverse authors as Flaubert, Loti, and Henri de Reignier. It also featured many critical essays by leading authorities on foreign literature while encouraging debate on related topics by devoting a large portion of the journal to letters from its enlightened readership. An avid reader himself, Zhang's induction into the Francophile salon was a defining moment in his literary career.

It is in the preface that he provided for Exotic Atmospheres that Zeng's influence upon his youthful prodigy is most apparent. Here, Zeng would write that despite their brief friendship, the discrepancy in their ages and their frequently divergent tastes, he and Zhang were united by their love of the city's exotic atmospheres. Calling upon the spirits of Chateaubriand and Mme de Staël, Zeng suggested that the doctrine of exotisme was the realisation of the French Romantic spirit on Chinese soil, a simple statement, which would help crystallize both Zhang's relationship with Shanghai and his literary vision. Not only did the city's exotic atmospheres allow those who had never ventured abroad enjoy la vie parisienne, they also served as a means by which the littérateur might draw close to the Romantic ideal of mankind's perfectibility, an aspiration that existed in the pure and eternal realm of art.

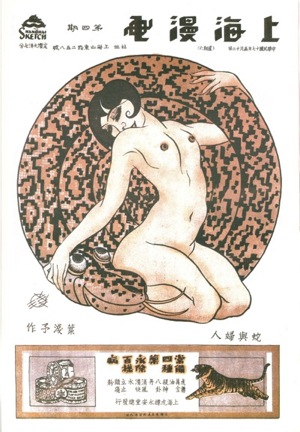

Fig.6 Ye Qianyu's playful 'Woman and the Serpent' Shanghai Sketch 12 May 1928

Massenet is the name of the modern French composer, and as soon as I step out onto the street, his operas LE ROI DE LAHARE and WERTHER spring to mind. Late in the afternoon as I stroll over the tightly knit shadows of the tree-lined walk, the tragic scenarios of LE CID and HORACE unfold on my left, vis-à-vis the RUE DE CORNEILLE. And on my right, from the RUE DE MOLIÈRE, the cynical laughter of a TARTUFFE or a MISANTHROPE seems to reach my ears. Horizontally in front of me stretches the AVENUE DE LAFAYETTE. Though France has many notable figures of this name, the one to which I refer is the female author, LAFAYETTE, who published under the name of SEGRAIS. This, in turn, evokes the scenery depicted in her LA PRINCESSE DE CLÈVES and the historic sites described in MEMOIRES INTERESSANTES. The French Park is my (Jardin du) LUXEMBOURG and the Avenue Joffre my CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES. My steadfast determination to stay in this area is solely rooted in this eccentric EXOTISME of mine.[44]

Implicit in Zeng's poetic portrait of the geography of his beloved French concession is the belief that even such indirect exposure to the icons of French culture might effect this moment of transcendence, a sentiment echoed in Zhang's homage to his new mentor, 'My First Meeting with The Sick Man Of Asia' (初次見東亞病夫). In a description worthy of a true Chinese flâneur, every step of Zhang's journey is simultaneously an excursion through the masterpieces of French culture from the sixteenth century to the present day. So immersed is this work in literary allusions that only rarely does the author allow the mundane world to impinge upon his idyll. As a consequence, the Chinese world is experienced only through its absence, the unseen merchant and plebeian families who reside in these Western villas where 'the nappies and ladies underwear strung across sun porches like flags' are tell-tale signs of Chinese occupancy.[45]

More than simply a record of the author's peregrinations through this quasi-imaginary landscape, 'My First Meeting with The Sick Man of Asia' is Zhang's account of his literary awakening in what was the epicentre of the exoticist world, the salon. For Zhang, entrée into this new world was nothing short of a revelation, for in this most exotic of corners he discovered a refraction of his inner world. While the city's cafés and concert chambers might evoke the ambience of foreign lands, the Francophile salon, with its affiliated publishing ventures, its highbrow discussions of Lu Xun and Brunetière, and its colourful cast of characters, was to him the very embodiment of the French literary spirit. In this sacred precinct, every mannerism, pattern of behaviour and conversation now assumed the role of ritual to be offered up as a confirmation of their claim to be the rightful heirs to this alien cultural heritage. Therefore, Zhang employs anecdotes of the legendary bohemian and bon vivant, General Chen Jitong (陳季同將軍), the work habits of the ailing Zeng Pu, whose maladies are seen as confirmation of his Romantic nature, and his own musings, which incite comparisons to the great Pouvillion, as further evidence of the deeply spiritual, aesthetic, and experiential bonds that tied Shanghai, and of course its literary élite, to the sublime and wondrous chimera that was Paris.

Zhang's attempt to build a connection with the French literary world was also evident in his translation of an essay by Anatole France entitled 'L'amour Exotique.'[46] Significantly, Zhang dedicated his translation of this glowing assessment of the novelist Pierre Loti to the Chinese translator of Loti's novel, Madame Chrysanthème, and fellow member of the Francophile salon, Xu Xiacun (徐霞村). As Zhang had acknowledged elsewhere, the works of Loti were held in high esteem by many and were a frequent subject of conversation amongst Zeng Pu's clique.[47] A former sailor turned highly prolific author, Loti had achieved fame for his idealised romances, which were invariably set in tropical and oriental settings including Constantinople, Tahiti, Senegal, and Japan. If Loti's preoccupation with the exotic backdrops provided justification for their own fantasies of foreign lands, then his style was also critical in shaping Zhang's latest collection. Within the impressionistic, sensuous, yet simple and musical timbre of Loti's work, which emphasised atmosphere rather than pictorial detail, Zhang finally encountered the technique that would allow him to depict the vague and elusive sympathies for the city of his birth.[48]

Zhang's creation of a realm in which the known physical world and that of the imagination converged would be his most significant achievement for it was destined to play a vital role in defining both intellectual and popular perceptions of Shanghai at the dawn of its Belle Époque. Yet, while contemporary scholars have acknowledged Zhang's role in the Republican intellectuals' construction of a new 'cultural imaginary,' most have overlooked the deeply personal motivations that inspired both Exotic Atmospheres and the doctrine of exotisme. While the essays 'The Seductive Metropolis' and 'The Stimulus of Spring,' together with Zhang's references to Zhou Zuoren's 'The Shanghai Style' in the preface to this collection all indicate that he was cognisant of the mounting criticism of the city, his real motivations were almost certainly less altruistic. If by immersing himself in the city's exotic atmospheres, Zhang was attempting to capture the suggestion of eternity that lay hidden within the confines of quotidian life, he was careful to stress the centrality of the artist in all such experiences. While maintaining the Occidentalist view that the city was the catalyst for mankind's transformation, Zhang stressed Baudelaire's belief that the poetic and marvellous subjects of urban life were indiscernible to all but the artist. What Zhang had garnered from the Francophile salon was a belief that the atmospheres in which he revelled were synonymous with the notion of a full artistic life of the senses.[49] Accordingly, this new artistic dogma allowed the author not only to experience, albeit indirectly, the Western aesthetic paradise of Paris, but to connect with a future Shanghai modelled upon the city of light, where he and his colleagues might enjoy the same esteem as their literary idols. The synthesis of art and life, Exotic Atmospheres was nothing short of a glowing endorsement for Zhang's indulgence in his highly contentious and increasingly unfashionable concept of 'la vie littéraire.'

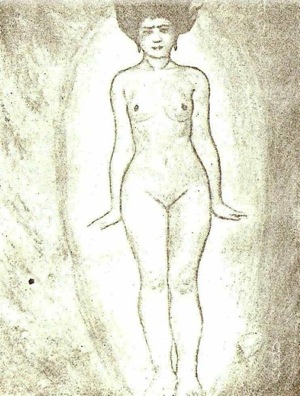

Fig.7 'Adam and Eve' Huang Wennong, Shanghai Sketch 4 August 1928

Susceptible to the tides of fashion and ideology, the true success of Zhang's vision would not be seen until the mid-1990s when a renewed interest in Republican Shanghai gripped the city. Almost seventy years on, his fantastic vision of Shanghai would once again resonate in the works of a new generation of authors, and in particular those of the popular writer Chen Danyan (陳丹燕). Published in 1998, Chen's Shanghai Memorabilia (上海的風花雪月), is a collection of personal essays that examines not only the author's relationship with the city, but that between Shanghai and its past. An homage to the city's cosmopolitanism, Chen would devote an entire chapter to her own experiences in major metropolitan centres such as New York and St. Petersburg, recording both the similarities and disparities between Shanghai and the artistic capitals of the Western world. Perhaps not surprisingly, Chen felt the greatest sense of belonging in Paris and it is in her own discovery of Shanghai in Paris that we can discern a distinct echo of both Zhang and Zeng Pu. For Chen, the plane trees and the boutiques of the Boulevard Saint-Germain bring to mind those along Shanghai's Maoming Road (茂茗路); while its late night restaurants remind the author of Huang He Road's (黃河路) numerous and perpetually busy eateries.[50] Though Chen claims never to have read the works of Zhang, clearly she is motivated by similar desires.[51] The very clichés that had subsequently come to define China's Queen of the Orient would be called upon once more to bridge the abyss separating Shanghai from the world and allow the residents of Shanghai to explore this new and rapidly changing urban environment.

Needless to say, Chen's exploration of the city would follow a similar route to Zhang's, for she too conceived of the old French concession as the very heart of the city's exoticism and its vibrant café culture as the most tangible symbol of Shanghai's modernity. While Chen invokes the spirit of Old Shanghai in her essays on the Peace Hotel and Café 1931 and describes the neo-colonial ambience of such legendary nightspots as Judy's Place and O'Malley's Pub, it is only in her essay, 'Times Café' (時代咖啡館) that the author inadvertently re-writes Zhang's portrait of the Café Tichenko.[52] Once again, the café is described in minute detail, from its softly spoken waitresses to the white pianola that plays tunes heavy with the ambience of foreign lands (異鄉情調). The variety of customers that visit this establishment at various times of the day and night are also the subject of Chen's gaze. These include the elegantly attired urban youths who armed with shopping bags and the ubiquitous mobile phone seek refuge in the elegant surrounds, entrepreneurs conducting business transactions, and young couples who wile away the hours discussing European fashions, real estate, and the best private schools. By building this atmosphere layer upon layer, Chen offers a fresh insight into the lifestyles of the new urban élites. In spite of this, the sensibility that shapes this essay is sharply divergent from Zhang's notion of exoticism. Chen perceives Shanghai's new urban spaces as the extension of the Shanghai alleyway or longtang (弄堂), thereby forcibly connecting the new Shanghai with its past.[53] In doing so Chen betrays her own origins as a native of Beijing, for the veneration of and nostalgia for this sense of community is identical to that exhibited by contemporary residents of Beijing who fondly recall the rapidly disappearing life of the capital's hutong. It is almost certain that Zhang would have found the true spirit of Shanghai's fin-de-millennium modernity in locations other than the Times Café, the refurbished colonial monuments on the Bund or leisure spots that sought to recreate the glamour of Republican Shanghai. Instead, the author would have looked to the steel cathedrals of Pudong, the works of the city's artistic avant-garde, the Parisian glamour of the Printemps department store (巴黎春天) on Huaihai Road (淮海路) or one of the Tichenko's many successors, such as the fabled café/bar, 1997.

Although Chen would stress the cosmopolitan nature of the Shanghai café, the world she depicts remains constrained by the limits of her imagination. Offering little more than a snapshot of urban life, the author emerges from her experience unchanged, oblivious to the potential awakening that such moments invariably offer. On the contrary, as Zhang observed the passing street traffic from the window of the Café Tichenko, he was acutely aware that those engaged in this urban drama were also acting out their aspirations for a new and brilliant world. 'A Quiet Moment at the Café Tichenko' was intended to confirm that that within these fragments of time there was a clear suggestion of an impending golden age. Hence, Exotic Atmospheres must be recognised as one of the significant works of the Nanjing decade. Not only did it manage to capture the spirit of the age, but by identifying the very psychological impulses that determined the city's transformation, Zhang pinpointed an essential quality of the Shanghai Style, one that would endure despite the vagaries of the city's history and remerge triumphant in the city's new era of prosperity. Like the common man, Zhang also engaged in this performance of modernity, one that would conclude with his rebirth as the very apotheosis of the new literary man.

La Vie Littéraire and the celebrity scholar

The life that presented itself to these fellows was divided by three elements; behind them a past forever destroyed, but with the still smouldering ruins of centuries of absolutism; before them the dawn of an immense horizon, the daybreak of the future; and between them something like an ocean … that separates the past from the future, which is neither one nor the other, but which resembles both at the same time, and in which one does not know at each step whether one is walking upon a seed about to spring up, or upon a plant just dead.

—From Alfred de Musset, La Confession d'un enfant du siècle (1836).[54]

Poor Alfred! He's a charming fellow and delightful in society; but between me and you, he never has written and never will write a line of poetry.[55]

Fig.8 Mythical Landscapes. Gustave Moreau 'Oedipus the Traveller or Equality before Death' c. 1888

In 'Stage of Dreams: The Dramatic Art of Alfred de Musset,' Herbert S. Gochberg writes that the young French author 'had spoken for an entire generation in the second chapter of La Confession d'un enfant du siècle.'[56] This truly remarkable feat had been achieved through de Musset's vivid portrait of a world in ruins, his elegy for lost heroism and lament for the glory of France destroyed along with the nation's shameful defeat at Waterloo. Although de Musset might be said to have captured the spirit of the age, his reputation would prove susceptible to the tides of fashion. Nevertheless, his words would continue to resonate in the literary salons of Shanghai almost a century later. From the above quote, it is evident that many Chinese intellectuals could have readily identified with de Musset's le mal de l'isolement. Not only had they also abandoned the certainties of the past (for as part of the May Fourth generation they had been instrumental in its demolition), they too were blighted by what de Musset considered to be the modern condition, specifically a sense of bewilderment at the chaos in which they lived. Alienated from life and politically impotent, they had withdrawn into the world of letters from where they hoped to exert their authority and guide the nation towards an enlightened future. However, even in this endeavour they were plagued by self-doubt. Once again, they could find a reflection of their predicament in the words of de Musset as they also 'loved the future but in the same way that Pygmallion loved Galatea; it was to them a marble love … they were waiting for it to become animate, for blood to flow in its veins.'[57]

Despite its clear relevance to the modern era, de Musset's novel failed to capture the imagination of the Republican intellectual and it was only thanks to Zhang that his works became a subject of discussion amongst the city's Francophiles. Still, as the Chinese intellectual who would draw most heavily on the work of de Musset, Zhang was himself only vaguely interested in the sober concerns that plagued his latest literary hero. Primarily, de Musset presented the young critic with a model for his own literary persona, an eclectic and imprecise entity that evolved in line with the fickle yet consistently Romantic tastes of the Shanghai literati. In this regard, Zhang was in tune with many of his generation, for as Leo Ou-fan Lee has noted, 'imitation of and identification with one's favourite Western authors was a central facet of this vogue of étrangerie,' a process which allowed the May Fourth intellectual 'to aggrandize oneself and one's favourite Western counterparts into heroic proportions.'[58] In examining the various motivations and manifestations of this Romantic fervour, Lee identifies two romantic prototypes: the passive Wertherian and active Promethean personalities which he identifies in Yu Dafu and Xu Zhimo respectively. Yet, unlike his more famous contemporaries Zhang seemingly vacillated between the two extremes, an author who while attempting to shape the world in accordance to his acute sensitivities, frequently preferred the protection afforded by his withdrawal into the realm of the senses. Within Zhang's awkward and often contradictory relationship with de Musset, it is possible to detect an integral aspect of literary life in the Nanjing decade and by extension the Shanghai Style itself. If the author was willing to reconfigure his environment to conform to an ideal of a civilised and artistic society, he was equally prepared to adapt his public façade to both reflect and conceal his extravagant personal ambitions.

Barely out of his teens, Zhang was naturally attracted by an author who had enjoyed such astonishing early success. Even before the publication of La Confession d'un enfant du siècle, de Musset's talent had been recognised by the influential critic Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve, who had introduced him to the Romantic cénacle of Victor Hugo. Only a few years later, at the tender age of twenty-six, he had published the autobiographical novel which would secure his place amongst the literary élite. Based upon his tumultuous relationship with the novelist George Sand, this was precisely the type of tortured romance to which so many of the Shanghai literati aspired. Somewhat fittingly, Zhang discovered de Musset at roughly the same age that the French author began his great affaire du Coeur. Yet, while Zhang might have idolised the central character, Octave, he himself was anything but a reformed débauché. Despite his fondness for autobiographical essays, Zhang avoided any reference to his own emotional entanglements. These he concealed beneath the innocent persona of a Mother's Boy, his religious convictions, and his behaviour, which in the words of one of his contemporaries, resembled that of 'a young maiden of yesteryear.'[59] His emotional immaturity notwithstanding, Zhang and his closest acquaintances could hardly fail to see the many conspicuous parallels between the two young men of letters. Zhang too was a youthful prodigy whose talent was fostered first under the patronage of the Occidentalists and later in the Francophile salon, where the Chinese Victor Hugo singled him out as a kindred spirit and a critic of astonishing sensitivity. For some there might well have been a correlation between de Musset's classic novel and Zhang's ambitious fictional debut, Urban Symphonies. Containing four vignettes with such florid titles as 'Moonlight Sonata' (月光秦嗚曲) and 'Étude in the Key of Solitude' (寂寞獨秦曲), Urban Symphonies was not only a portrait of the new metropolitan life but the author's reflections on the modern condition and an exploration of themes as diverse as love, sorrow, and the synthesis of art and life.[60]

Zhang's fixation on de Musset is evident in many of his essays written between 1928 and 1929, in which he repeatedly refers to the seminal work of the young French author. For Zhang, La Confession d'un enfant du siècle served many purposes: it reinforced the French ambience of his essay, 'A Quiet Moment at the Café Tichenko,' inspired debate with his peers, and offered justification for his unique interpretation of the concept of mal du siècle. Yet, even amongst Zhang's pantheon of literary greats, de Musset was unique. While he might have to share other literary icons such as France, Verlaine, and Baudelaire with his peers, de Musset was his exclusive property. Eager to impress his mentors within the Francophile salon, Zhang could now establish himself as the undisputed authority on a figure who, alongside Hugo, Lamartine and Vigny, was regarded as vital to the development of Le Romantisme. Despite this, Zhang's adulation lacked the almost religious intensity he accorded to the literary giants of the nineteenth century. If Zhang did not heap upon de Musset the superlatives reserved for the most fashionable French authors, it was because de Musset served a very different but no less significant role in his literary life. While Zhang knew he could never attain the heights of France or Baudelaire, de Musset offered him a glimpse into a world in which his literary ambitions were realised; a niche in which he might conceal his secret dream of fame.

Few intellectuals of the Nanjing decade can be said to have worked so assiduously towards achieving the goal of literary celebrity. From his appearance on the Shanghai wentan at the age of nineteen, Zhang proved to be a highly prolific author, translator, and interpreter of the Western musical and literary canons. His numerous essays, which first appeared in the literary supplements of leading newspapers and the journals produced by his mentors, were then collated in book form, creating an astonishing body of work for one so young.[61] Yet, his writings were only one means by which Zhang sought to garner the attention of his peers and the reading public. Zhang was equally adept at social networking, becoming a cornerstone of the city's salon culture and a familiar face at the literary gatherings held at cafés and restaurants across the city; a man who avoided personal frictions and rivalries and developed friendships with some of the most prominent literary personalities of the day. He was also an ebullient critic whose lavish praise of his colleagues fostered the cult of the celebrity-scholar. While he shared this formula with many of his like-minded peers, what makes Zhang so unique is that he left a detailed record of this mammoth undertaking in the two volumes of essays, La Vie Littéraire (1928) and Café Confabulations (1929).