|

||||||||||

|

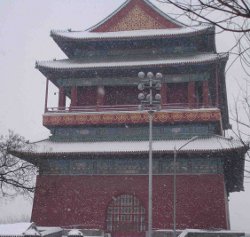

ARTICLESChina’s PromiseGeremie R. BarméThe following essay, which in part reiterates, but then extends, our discussion of New Sinology, was first published on 20 January 2010 by China Beat, and variously reprinted by the History News Network and China Digital Times. A shorter version of this essay appeared in East Asia Forum published by The ANU. I am grateful to the editors of China Beat for permission to reprint this work here. A Year of Anniversaries Fig.1 ‘Welcome with Joy the Sixtieth Birthday’ (Xiying 60 huadan), Ri Tan Park (日坛公园), Beijing. (Photograph: GRB, October 2009) The year 2009 was marked by a series of important anniversaries in the history of the People’s Republic of China. Some of these were commemorated with due pomp and circumstance in the official media and dissected at length during learned gatherings and discussions. Others, those events that I think of as ‘dark anniversaries’, passed by in an atmosphere of heightened alertness, surveillance and official anxiety. Dark anniversaries are the signposts of quelled protests, social unrest and state violence, events such as the 1959 rebellion in Lhasa, the shutting down of the Xidan Democracy Wall in Beijing in 1979, the tragedy of the 1989 protest movement and the religious repression of 1999. Such events offer alternative narratives to the official Party-state story of modern China; an understanding of them also contributes to our appreciation of the ways that the strong unitary state, and its anxieties, has evolved over the past decades. The ‘forgotten dates’ in the official Chinese calendar offer a penumbra of history; they stand in shaded contrast to vaunted moments the commemoration of which is carried out in the merciless glare of publicity and official largesse. Although formally ignored, or recalled only in verso, the dark anniversaries cast a gloomy shadow over the orchestrated son et lumière of state occasions.[1] Only days after the 1 October 2009 celebration of the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in Beijing, the Chinese Premier, Wen Jiabao 温家宝, paid a state visit to North Korea. During his stay in Pyongyang, Wen visited the memorial to the fallen members of the Chinese ‘volunteer army’ that had fought alongside Soviet and Korean communist forces during what is known in China as the ‘War to Oppose American Aggression and Support Korea’. Among the war dead is Mao Anying 毛岸英, the favoured son of Mao Zedong, the founding leader of the People’s Republic. After laying a wreath at Anying’s tomb, Wen directly addressed a stone likeness of the dead soldier. He said: ‘Comrade Anying, I have come to see you on behalf of the people of the motherland. Our country is strong now and its people enjoy good fortune. You may rest in peace’. (Anying tongzhi, wo daibiao zuguo renmin lai kanwang ni. Zuguo xianzai qiangdale, renmin xingfule. Ni anxi ba. 岸英同志,我代表祖国人民来看望你。祖国现在强大了,人民幸福了。你安息吧。[2] Although this statement passed by the media with little comment, among well-informed friends in Beijing Wen’s was seen as a remarkable utterance. Some argued that, in essence, it meant that a contemporary Chinese leader was declaring that the efforts to create a strong and prosperous nation—a Herculean enterprise that has inspired and haunted Chinese thinkers, politicians and people for over a century—have to all intents and purposes borne fruit. Taking things one step further it would seem that, in offering consolation to the long-dead son of modern China’s founder, Wen was also declaring that the mission of the ‘Chinese revolution’ had been achieved. If, friends remarked to me in private, the revolution is over and the aims of the Communist Party all but achieved, then what will the next grand mission of the Chinese nation be in the twenty-first century? As China continues along the trajectory it is enjoying as a strong, and increasingly willful, modern power it therefore becomes necessary to speculate about the future enterprises of not only the Party-state that rules China, but of the Chinese people collectively. While the orchestrated mass celebrations of the People’s Republic were being held in Beijing, thoughtful writers and thinkers recalled the solemn undertakings that had originally brought the Chinese Communist Party to power shortly after the Second World War. In a country racked by years of invasion and internecine strife and economic collapse, at that time the Communists not only offered national unity and economic stability, they also won over the urban classes and intelligentsia by declaring that they would create a polity that instituted political democracy and secured human rights in ways unachieved by the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek. During the late 1940s, in countless essays, editorials, speeches and documents, time and again China’s revolutionary leaders undertook to fulfill the promise of China’s original revolution of 1911 that had seen the end of dynastic autocracy. It was a promise to realize national prosperity and democratic politics.[3] Broken Promises Fig.2 The Gate of Divine Prowess (Shenwu Men 神武门), north entrance to the Palace Museum, Beijing. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010) Not long after achieving power in 1949, the Communists forged a regime that ensured national stability but they soon betrayed their commitments to bring true democratic rule and economic prosperity to the peoples they now ruled. After three decades of increasingly radical totalitarian experimentation and the disastrous denouement of the Cultural Revolution era, in late 1978 the Party-state returned to another part of its original undertaking, to ensure economic prosperity for the nation. Although China has experienced unprecedented economic transformation and global integration in recent decades, nonetheless the long-term political and social transformation of the society proffered so long ago remains unrealized. Nothing made this more evident than the detention in late 2008 of the writer Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波. Liu, a cultural and political critic who has enjoyed (mostly unofficial) prominence since the mid 1980s, is also a leading pro-democracy activist. He helped draft Charter 08, a petition calling on China’s Communist Party to honour the state constitution and fulfill its historical pledges to undertake political reform. That petition garnered the signatures of leading public intellectuals and concerned citizens before harassment and police questioning halted its progress in the dying weeks of China’s eventful Olympic Year of 2008.[4] On Christmas Day 2009, as a momentous year of anniversaries drew to an end, the Beijing authorities announced that Liu Xiaobo had been sentenced to eleven years in jail for ‘inciting subversion’. According to media reports, this was the longest term given to any offender accused of this particularly nebulous crime since it was introduced in 1997. Ironically, for the two decades since the tragic denouement of the 1989 mass protest movement that pressed for media freedoms and basic rights Liu’s has been a voice of reason and decency. Like patriots who had agitated for the Party to make China a modern and civil nation in the 1940s, activists like Liu, and the thousands who signed the Charter 08, have used peaceful means and public protest to appeal to Chinese authorities to respect their own constitution.  Fig.3 The Drum Tower (Gu Lou 鼓楼), Beijing. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010) As China continues on its path to become a major world influence, it is important that we remain heedful of the complex realities of China’s society and the varying demands of its citizens. As international criticisms of China’s failure to realize a social and political transformation concomitant with its economic achievement, the Chinese authorities have become increasingly anxious to present their monolith version of Chinese reality to the world as the only truly Chinese story worthy of our consideration. The Chinese Party-state, with the support of many citizens nurtured by a guided education and media industry, is now investing massively in presenting what it calls the ‘Chinese story’ (Zhongguode gushi 中国的故事) to the rest of the world. However, in doing this, it constantly limits and censors the variety of stories and narratives that make up the rich skein of human possibility in China itself. To many it would appear self-evident that no political force can or should claim to represent in its entirety or in perpetuity such human richness. In the case of the sentencing of Liu Xiaobo, for example, we should be aware that leading Chinese thinkers condemned a decision that was obviously politically motivated, an abuse of legal norms and another indication that the Party-state is fearful of reasoned and legitimate opposition to autocratic rule. The Chinese media could not report their views, but they are available on Twitter. In January 2010, for instance, an unofficial (and in China unpublishable) poll of leading thinkers, rights activists, lawyers and writers, was unanimous in condemning the absurd charges against Liu and the harsh sentence meted out to him by the Party-dominated legal system. A random selection of the numerous comments, collected by the prominent cultural critic, translator and writer Cui Weiping 崔卫平, is worthy of consideration here: Ding Dong (丁东 cultural critic): From ancient times essays have led to many unjust jailings, now another eleven years has been added to the record. Thought always demands its freedom, not only in ’08.—Christmas in China. 文章自古多奇狱,又添十一载;思想从来要自由,何止零八年。——圣诞中国 I would note in passing that in Cui’s list of some ninety Chinese thinkers, it would appear that those with a more avowedly ‘left-leaning’ caste (that is those who generally provide some kind of academic and intellectual rationale for Party-state dominance albeit in the guise of Euro-American neo-Marxism), seem uncharacteristically at a loss for words. Indeed, even the most enthusiastic advocates of the regnant Party-state blather inanities and bromides when confronted with the kind of pitiless political and intellectual censorship as evinced in the case of Liu Xiaobo. Party EmpireDespite an extraordinary array of media publications and new voices in the Chinese public sphere, the public is still not allowed access to an unfettered range of views and debates on a range of subjects—whether it be the case of Liu Xiaobo, or local governance, or questions related to corruption or Copenhagen, the continuing situation in Tibetan China or the unrest in Xinjiang. Such guided and paternalistic policing of opinion and discussion continues to foster a kind of state demagoguery, and popular zealotry, that already has and will continue to have baleful consequences for China as a global presence.  Fig.4 ‘Warmly Celebrate the Sixtieth Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China’ (Relie qingzhu Zhonghua renmin gongheguo chengli 60 zhounian), North Third Ring Road, Beijing. (Photograph: GRB, October 2009)

If China is to be a responsible member of the international community, and for its peoples to be a harmonious part of an equitable world order, the citizens of the People’s Republic not only need to be informed and to inform of their views, but be free to debate, disagree and reach social and political consensus in a way that is not determined behind closed doors, or predominantly by a secretive political system with complex corporate ties in which family connections, personal wealth and power form the only basis for true legitimacy. In the 1940s a number of Chinese writers, reporters and thinkers were wary of the Communist Party’s promises to bring democracy and freedom to the country. In 1956, the noted publisher and writer Chu Anping 储安平 warned of the rise of what he dubbed a ‘Party Empire’ (dang tianxia 党天下). Like so many others who spoke out as part of a movement that the Party launched so it could ‘correct its mistakes’, Chu was soon purged for his outspokenness. Eventually, he disappeared in mysterious circumstances in 1966. To this day the expression ‘Party Empire’ resonates powerfully among those who are fearful of the swagger and style of a regnant Communist Party that along with a newfound economic clout cleaves to its backward-looking autocratic habits. Some now discuss the baleful consequences that this kind of ‘Chinese story’ could have on a global scale. Another China StoryWe as individuals, societies and countries engaged with China in multifarious and changing ways are also challenged to find creative paths to deal with and offer insights into not only the main ‘story of China’ that the Party-state promotes, but also into the rich variety of Chinese histories, cultures and realities that make China and the Chinese world an extraordinary global presence. One approach can be described under the rubric of what I choose to call ‘New Sinology’.[6] This is an expression that I first used in 2005 when founding the China Heritage Project at The ANU with a colleague. Simply put, and to quote my initial essay on the subject, New Sinology is: descriptive of a robust engagement with contemporary China and indeed with the Sinophone world in all of its complexity, be it local, regional or global. It affirms a conversation and intermingling that also emphasizes strong scholastic underpinnings in both the classical and modern Chinese language and studies, at the same time as encouraging an ecumenical attitude in relation to a rich variety of approaches and disciplines, whether they be mainly empirical or more theoretically inflected. Furthermore, it is an approach: that recognizes an academic and human relationship with a vital and voluble Sinophone world that is not just about the People’s Republic, or Taiwan, or Chinese diasporas. It bespeaks an involvement that is part of the intellectual, academic, cultural and personal conversations in which many of us are engaged, not merely as Australians, but as individuals, regardless of our background, individuals who are energetically and often boisterously interconnected with one of the great, complex and lively geo-cultural spheres of the world.  Fig.5 Zhengyang Men and Qian Men (正阳门及前门), with the Mao Zedong Mausoleum in the distance, Tiananmen Square, Beijing. (Photograph: GRB, December 2009)

A New Sinology, or a more profound and humanly rich engagement with China and the Chinese world, is not a study of an exotic, or increasingly familiar Other. It is an approach that also constitutes a concerted attempt to include China as integral to the idea of a shared humanity in all of its contradictory, unsettling as well as inspiring complexity. It is a study, an engagement, an internalization that enriches the possibilities of our own condition. In that initial essay on the subject of New Sinology I also spoke of our critical engagement being: with a language and a culture that has already altered our Anglophone habits of mind: an ‘Other’ that haunts us from within, in the sense of a common humanity that Pierre Ryckmans evocatively affirmed, using the phrase ‘we are all Chinese’; or which Benjamin I. Schwartz spoke of as part of the enterprise to ‘bring the experience of the entire human race to bear on our common concerns.’ Nor is this merely an engagement in one direction. For to talk of some divide, some chasm that has to be bridged or crossed, is to accept too easily the belief that difference predominantly creates barriers and distances. It also limits us unnecessarily to the idea that studying about China, learning its languages, cultures and thought systems is to limit ourselves to being interpreters of a ‘correct’ view of what China and Chineseness is. While such linguistic and cultural translation is essential for the growth of all peoples, our engagement with China is not merely that of sophisticated interpreters equipped through dint of hard work and long years of study with some privileged insider knowledge. In thinking about Chinese realities, we are concerned not only with the issues of the day but also with the complex origins of those realities and the Chinese possibilities for tomorrow as well. Just as the Anglophone world—that is the linguistic realm that started out limited to the British Isles—has become part of world culture, as have French and Spanish and Arabic, the Sinophone world is likewise one of global reach. Its ‘hybridity’ adds to lives, thinking and feelings wherever it extends. I believe that we, and more importantly, those who are being educated in Chinese now as well as those who will be literate in Chinese in the future can and will be co-creators in this process. Young people—no matter of what ethnic or multi-ethnic background—are and will be part of this extraordinary new era of human engagement in which Chinese languages and cultures are increasingly part of the global world. I would point out that many Australian-born Chinese are, while pursuing various careers or studies, also interested in learning more about the Chinese world from which their forbearers come. Similarly, many students from the People’s Republic, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or ethnically Chinese students from the region, study China-related subjects at tertiary institutions. Co-creating China for them, and for students of other backgrounds, is part of what should and will be possible. Writing, thinking and creating in Chinese, not as merely passive receptors, not just to be told tirelessly what ‘We Chinese’ think, is, I would suggest, part of the way that a developing enmeshment with the Chinese world is already unfolding for many young people. We have already seen such an evolution and interaction throughout East and South-East Asia, where Chinese languages, cultures and communities descended from various provincial or local Chinese areas, religions and thinking systems have been part of the fabric of diverse societies for many years. We have seen too how the ‘Kong-Tai Ark’ (see, for example, my book In the Red, Columbia University Press, 1999)—that is the world of Hong Kong and Taiwan not dominated by the Chinese Communist Party from the 1940s—played a crucial role in China’s mainland reinvention of itself from the late 1970s. We have also seen how the waves of cultural fashion, imbricated with economic exchange with Korea and Japan, have contributed to the richness of modern Chinese identities.  Fig.6 On Qionghua or Jade Island (Qionghua Dao 琼华岛), Bei Hai Park (北海公园), Beijing. (Photograph: GRB, January 2010) English as a global language used in every sphere of human activity has been transformed and immeasurably enriched by its non-Anglo-Saxon users. So too will the Sinophone world be enriched and enhanced by the growing communities of users of Chinese who learn, employ and creatively engage with living Sinitic legacies. Speaking, using, writing Chinese, imagining through Chinese, creating with Chinese colleagues—these are all acts that enrich not only those who live in Chinese but those who grow through Chinese, adding thereby to the multifarious heritages of the Chinese world. Just as countless Chinese people young and old study, live and travel internationally, so do people from countries throughout the world go to study, live and travel in China. They have been lured by the economic boom and employment opportunities, by educational opportunities, or just by the desire to see what is happening in a place that has been the talk of the world. Many I have encountered have found employment in big cities, or in teaching, or in entertainment, or in a host of other professions. Indeed, it has been the fashion these last few years for Chinese firms to employ a foreigner or two who can speak Chinese to make PowerPoint presentations at meetings with new business partners, or for ‘display’ during negotiations, or even to play the role of a foreign ‘rent-a-date’ for social occasions with business people. (This is a practice familiar to many from earlier days in Hong Kong and Taiwan, or equally for those familiar with business practices in Japan or Korea.) When I speak of the creative engagement with the evolution of the Sinophone world, I do not just mean that foreigners will be a trendy accessory or a useful tool. Just as those young people of Chinese background will have an impact on world culture and that of their places of origins, so will those cosmopolites with no Chinese background who are now making the Chinese world the ‘habitus’ for their creativity. It is the stories of these individuals and groups that will also form part of the pluralistic ‘Chinese story’ that is part of the global story of humanity. And it is in its telling that the other promise of China will be realized. Notes:[1] For more on the anniversaries of 2009, see the March and June issues of China Heritage Quarterly at: www.chinaheritagequarterly.org [2] For a report on Wen Jiabao’s trip to North Korea, see ‘温家宝专程赴志愿军烈士陵园凭吊’ at: http://news.sina.com.cn/c/p/2009-10-05/171116399003s.shtml [3] For an important, and unique, collection of articles, speeches and editorials by Communist writers and leaders on how the Communist Party would institute democracy and human rights in a New China, see Xiao Shu 笑蜀, Lishide xiansheng—bange shijiqiande zhuangyan chengnuo 历史的先声——半个世纪前的庄严承诺, Shantou: Shantou daxue, 1999. This volume was published in time for the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic in 1999. It was soon banned. [4] For details of Charter 08, see http://charter08.eu/2.html [5] For the comments by leading public intellectuals on the sentencing of Liu Xiaobo, see Cui Weiping’s phone and email interviews published via Twitter: ‘崔卫平就刘晓波案访谈中国知识分子’, at: https://isaac.dabbledb.com/page/isaac/NRJznSaR# [6] For more on New Sinology, see the essays at: http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pah/chinaheritageproject/newsinology/ |