|

|||||||||

|

ARTICLESTreasures from the Chu Valley of Kings Fig. 1

Jade ge weapon

Fig. 1

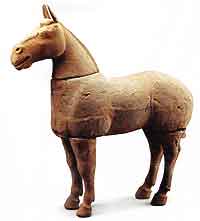

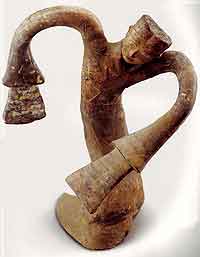

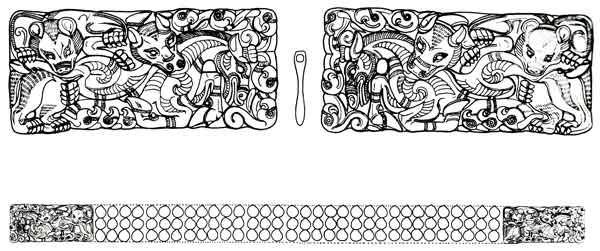

Jade ge weapon2nd century BCE Width, 17.2cm; Height 11.2cm Unearthed in 1994-1995 from the king's tomb at Shizishan 'Tombs of the Chu State in the Western Han Dynasty" is the less than catchy English title of a major archaeological exhibition running through to 20 April 2006 at the National Museum of China. The exhibition displays some of the most impressive finds of the past two decades excavated from the royal tombs in the vicinity of Pengcheng, capital of the Chu kingdom.  Fig. 2 Jade zhi cup 2nd century BCE Height, 11.8cm; Diameter of mouth, 6.7cm Unearthed in 1994-1995 from the king's tomb at Shizishan  Fig. 3 Jade dragon 2nd century BCE Length, 17.5cm; Width, 10.2cm Unearthed in 1994-1995 from the king's tomb at Shizishan The ancient city of Pengcheng was located near today's Xuzhou in Jiangsu province, and the exhibition displays 190 objects from the Xuzhou Museum, few of which have previously been seen in Beijing. These items were excavated from tombs named for the hills around Xuzhou in which they were located—Beidongshan, Chuwangshan, Dongdongshan, Shizishan, Tuolanshan and Yangguishan. The Chu kingdom, perhaps more accurately regarded as a "principality", was located in the Chu homelands of Liu Bang, founder of the Han dynasty. The four centuries of Han rule were later divided by historians into the Western Han dynasty (206BCE-24CE) and Eastern Han dynasty (24-220CE), because of the break in historical continuity created by the interregnum of Wang Mang (8-23). The Han dynasty's Chu kingdom was ruled for more than two centuries (202BCE-8CE) by kinsmen of the Han emperors. Archaeological excavations over recent years have revealed that great power and wealth accrued to the rulers of the various kingdoms both related to, and enfeoffed by, the Liu imperial household of the Han dynasty. At the outset of the Han dynasty there were ten kingdoms scattered throughout the eastern territories of the Western Han dynasty, but few rivalled Chu. Two centuries later, at the close of the Western Han dynasty, there were about twenty kingdoms. In all, twelve kings of Chu are buried in the royal mausoleums near Xuzhou. After Liu Bang deposed the first king of Chu, Han Xin, who had ruled for only two years, and installed Liu Jiao (r.201-179BCE), the twelve successor kings of Chu were all descendants of the Liu clan, the ruling family of the Western Han. The imperial household appointed most of the officers who served the kings of Chu.  Fig. 4 Jade ornament 2nd century BCE Length, 14.3cm; Width, 4.5cm Unearthed during 1994 and 1995 from the king's tomb at Shizishan  Fig. 5 Dragon-shaped jade pendant ornament 2nd century BCE Length, 18cm; Width, 11.9cm The Chu kingdom had its pedigree in the rich and ancient culture of the Chu region that extended back for at least five centuries prior to the establishment of the Han dynasty. Having its homeland in Chu, the Liu imperial household also brought craftsmen with them to the northern court in Chang'an (near present-day Xi'an) as well as a taste for the lyrical art styles of the ancient Chu region, exemplified by the archaeological finds at Mawangdui, thus defining Han dynasty art. The difference between northern and southern sensibilities is exemplified, in the literary tradition, by the contrast between the formal metres of Shi jing (The Classic of Songs), said to have been anthologised by Confucius himself, and the shamanic flow of Chu ci (The Songs of Chu), ascribed in part to Qu Yuan. The former work eulogises the worldly joys and political triumphs born of the more austere and arid northern environment, while the latter work is redolent of the mythology and luxury derived from the southern landscapes steeped in mists and rain. Through the objects in this exhibition, almost all of which date from the 2nd century BCE, visitors can see how the art of Chu in the Western Han dynasty also represented a blending of northern and southern styles, and foreign influences can also be discerned in the Chu art of Pengcheng, especially in gold working techniques.  Fig. 6 Jade beast head 2nd century BCE Height, 5.8cm; Width, 5.4-11.5cm The majority of the items on display come from the excavated sites near Xuzhou mentioned above, but the most spectacular are from the largest tomb at Shizishan. In 1984 a large number of warrior and horse figurines were recovered from a pit at the western foot of Shizishan (Lion Hill), now the site of the Xuzhou Han Warrior and Horse Figurine Museum. In 1991 a massive tomb adjoining this warrior pit was discovered, and it was excavated, from late 1994 to 1995, by local archaeologists and a team from the Nanjing Museum.  Fig. 7 Jade shroud sewn with gold wire 2nd century BCE Length, 175cm; Width, 68cm The tomb, even though extensively plundered, contained more than 2,000 interesting objects. Although a number of tombs of the princes of the Chu state have been excavated near Xuzhou, this was the largest. Judging by the tomb structure, the funerary objects and the fact that some sections of the tomb were unfinished, the tomb occupant would appear to have been Liu Ying, a second generation king of Chu, or his successor Liu Wu, who was buried at some time between 175 and 154BCE. Some scholars have argued that because Liu Wu committed suicide after his rebellion was defeated by the Western Han central government, it is quite possible that Liu Wu was the king buried in the uncompleted mausoleum. Despite the valuable hoard found in the tomb, it had been robbed, possibly at some time during the Wang Mang interregnum.  Fig. 8 Jade headrest 2nd century BCE Length, 37.1cm; Width, 16cm; Height, 11.4cm Unearthed in 1991 from Han tomb no.1 at Houloushan  Fig. 9 Jade bi sword ornament 2nd century BCE Length 6cm; Width 4.6-5.9cm Unearthed in 1986 from the king's tomb at Beidongshan This massive tomb is distinguished by its unusual structure: it comprises an inner and outer tomb, as well as side chambers. The inner tomb was more carefully constructed than the outer. There was also an ancillary tomb at the northern end of the complex. Three of the side chambers had not been discovered by tomb robbers and they were found to contain bronze and iron weapons, bronze containers, jade items, lacquer articles, clay seals, silver items, and pottery cooking implements, as well as carbonised cereal grains and fish bones. Other side chambers branched off the tomb's vaulted passage, which was divided by sixteen enormous stone slabs. Gold, silver, bronze, iron, stone, pottery and jade objects that had escaped earlier tomb robbers were discovered both in the vaulted passage and in the side chambers.  Fig. 10 Jade open-work ring 1st century BCE Diameter, 7.9cm Unearthed in 1982 from the queen's tomb no.2 at Dongdongshan JADESIn the pre-Qin period, jade commanded less attention from Chu artists than did timber and lacquer ware, but by the Western Han that situation had changed. The most spectacular finds from Shizishan were probably the jade items, many of which are on display in the exhibition. The side chambers off the vaulted passage at the Shizishan tomb complex contained many exquisitely carved jade objects, including a jade dancer, bi discs, jade pendant components called huang and heng, a chicken-heart shaped jade plaque, dragon-shaped jade plaques, jade ear and nose stoppers. (Figs 1-6) Although the Shizishan tomb had been robbed, an enormous number of relics were found during the 1994-1995 excavation, but the jades are undoubtedly the most striking artefacts. Among these was a complete jade suit (Fig.7) and 1,809 pieces of jade used to decorate the coffin. These jade pieces, which were mostly triangular, rectangular or rhomboid in shape, had been scattered by tomb robbers, making it difficult to reassemble them on the coffin. After comparison with a jade-decorated coffin found in the Han tomb of Dou Wan in Mancheng, Hebei province, archaeologists devised a plan for restoring the design, based on the inscriptions that appear on the jade pieces. The impressive results of the eighteen-month restoration project are now on display in the National Museum of China.  Fig. 11 Jade pendant ornament 2nd century BCE Length, 5cm; Width, 3.9cm Unearthed in 1986 from the king's tomb at Beidongshan  Fig. 12 Jade headrest 2nd century BCE Length, 28.7cm; Width, 9.5cm; Height, 8.5cm Unearthed in 1996 from Liu He's tomb at Huoshan Jades from other Chu sites, including Beidongshan, Houloushan and Huoshan, are also included in the exhibition. (Figs 8-12) SEALS Fig. 13 Bronze seal with inscription Chuhou zhi yin 2nd century BCE Overall height, 2.1cm Length, 2.2cm Width of seal, 2.1cm Unearthed in 1994-1995 from the king's tomb at Shizishan The exhibition opens with a display of twenty-four seals. These create the historical setting for the other displays, and place the finds within a literate context. Although one seal is made of gold and another of silver, the rest are either square seals made of bronze or are clay seals (called fengni). During the excavation of the king of Chu's mausoleum at Shizishan, more than 200 official seals and some eighty clay seals were found in a wooden case. According to the excavators, official titles of twenty-two central government offices and nineteen local administrative titles that appear on these seals have been identified. Scholars who have examined the seals say that the titles recorded on them conform to the titles recorded in Han shu, the official history of the Han dynasty. This reveals that the administrative apparatus in place in the Chu kingdom largely replicated that of the Han central government. The seals can also be functionally divided into three categories: those of court officials, military officers and local bureaux. Thirteen official titles, including Chu hou (Marquis of Chu), (Fig.13) Chu Zhongzhou and Chu Taipu have been identified in the first category, eight in the second and nineteen in the third. Twelve seals belonging to local officials were also unearthed from another Western Han tomb near Xuzhou in 1986. These seals reveal the names of approximately two thirds of the total of thirty-six counties established in the Chu kingdom.  Fig. 14 Pottery soldier figurines with weapons in hands 2nd century BCE Height, 48.5cm Unearthed in 2005 from the pit at Yangguishan In general, Han officials were buried with their seals, but the Shizishan mausoleum demonstrates a different practice, that is, diverse official seals rather than only the king's seals were discovered, and most of these seals had not been used prior to their burial. In 155BCE, two prefectures within Liu Wu's territory were seized by the central government and Liu took part in a rebellion against the central government in the following year. Some scholars suggest that Liu Wu dreamed of rebuilding his kingdom and prepared new official seals after the contraction of his domain. STATUARY Fig. 15 Pottery horse figurine 2nd century BCE Height, 64cm Unearthed in 2005 from the pit at Yangguishan  Fig. 16 Painted pottery guard figurines 2nd century BCE Height, 49.5-50.5cm Unearthed in 1986 from the king's tomb at Beidongshan Examples of stone, terracotta and bronze statuary produced in the Chu kingdom are also on display in the exhibition. Unlike the rigid, formal and more detailed statuary that developed in northern China, of which a good example are the Qin dynasty armies of terracotta warriors at the mausoleum of Qin Shihuang, the statuary that developed in pre-Han southern China was more graceful and flowing, while the lines were more simple. In the Han dynasty the different styles blended. The dramatic contrast between the pre-Han northern style and the Han northern style can be seen from the armies of warrior figurines found in the course of the excavation of the Han and Chu royal tombs. (Figs 14-16) The warrior figures from the Western Han dynasty Yangling mausoleum at Xianyang, Shaanxi province, and the Shizishan royal and ancillary warrior pit tomb are very different from the figures constituting the armies of Qin Shihuang. The fluid sculptural style of the Chu kingdom can best be seen in the figurines of dancers and performers from the Tuolanshan Chu tomb, and superb examples of these figurines are on display in the National Museum of China. (Figs 17-21)  Fig. 17 Pottery dancer figurines 2nd century BCE Heights 47cm and 49cm Unearthed in 1989-1990 from the king's tomb at Tuolanshan  Fig. 18 Pottery dancer 2nd century BCE Height, 44.7cm Unearthed in 1989-1990 from the king's tomb at Tuolanshan  Fig. 19 Pottery dancer 2nd century BCE Height, 45cm Unearthed in 1989-1990 from the king's tomb at Tuolanshan One of the most impressive sculptural items on display is a stone tomb guardian figure from the Shizishan tomb, described as a hunting leopard in the exhibition catalogue. (Fig. 22) Although the cheetah was used for hunting in ancient China, this leopard was possibly a status symbol because in view of its plumpness it would not have been an ideal hunting animal. However, its association with the hunt is suggested by the cowry shell choker it wears around its neck. Belts decorated with cowry were attributes of warriors, as can be seen on terracotta figurines of two rows of warriors excavated from the accompaniment burial pit no.20 attached to the Yangling mausoleum. Three rows of cowry shells also decorate a golden belt excavated from the Shizishan tomb; the buckles from that belt can be seen in Fig. 23. Despite the fact that the hunting leopard from the Shizishan tomb wears a shell choker it was not necessarily trained to hunt, and warriors may simply have used it as a mascot during military exercises.  Fig. 20 Pottery musician playing the se; 2nd century BCE; Height of musician 33cm; Length of se 54cm; Width of se 14cm; Unearthed in 1989-1990 from the king's tomb at Tuolanshan  Fig. 21 Pottery figurine of musician striking stone chimes; 2nd century BCE; Height, 32cm; Unearthed in 1989-1990 from the king's tomb at Tuolanshan BRONZEChu bronzes, too, have simpler lines than earlier pieces from the Zhou dynasty, (Fig. 24) although this perhaps simply reflects the fact that the Chinese age of bronze had passed. Gold, however, seems to have been highly revered at the Chu court and to have commenced its ascendance. (Fig. 25) GOLDAmong the finds at Shizishan were two gold belt buckles bearing a design of a tiger and a bear attacking a horse. (Figs. 23 and 26) Similar depictions of animals in combat have been discovered on six plaques recovered in the 1950s from the tomb of a Han dynasty official of the Nanyue Han dynasty kingdom in Guangzhou, as well as on a number of plaques found in 1986 in the tomb of the King of Nanyue, also in Guangzhou. A screen pedestal in the tomb of the King of Zhongshan, another Han dynasty kingdom, located in Pingshan, Hebei province, depicts two tigers locked in combat in a similar style. This "animal style" has been identified as originating among the nomadic people of the ancient Eurasian steppes known as the Saka and called by the Greeks the Scythians. These cultural influences may have been introduced to China by the Xiongnu people, or they could have come to China along the ancient trade routes from Central Asia first opened up in the Han dynasty.  Fig. 22 Leopard-shaped stone sculpture; 2nd century BCE; Length, 23.5cm; Width, 13cm; Height, 14.5cm; Unearthed in 1994-1995 from the king's tomb at Shizishan IRON WEAPONSTwenty-one iron and steel objects, including weapons, tools and a piece of a vessel unearthed from the Shizishan tomb, were examined at the laboratories of the Institute of the History of Metallurgy and Materials at the Beijing Science and Technology University using metallographic analysis. Iron and steel artefacts from six other princes" tombs dated to the same period were also examined as a comparison. The results indicated that these iron and steel items could be classified as belonging to the following types: cast iron, solid state decarbonised steel, malleable cast iron, bloomery iron produced directly from malleable iron, carbonised steel and puddling iron. The tests also revealed that they were produced using the techniques of quenching and cold working. This suggests that blacksmiths and foundrymen had made great advances in iron and steel making and heat treatment techniques during this period. The five items unearthed from the Shizishan tomb and classified as puddling iron, which is a type of wrought iron made from pig iron by heating it with ferric oxide in a furnace, are the earliest ever found in China, and it has been confirmed that the technology for producing puddling was invented in the mid 2nd century BCE. Many examples are included in the exhibition.  Fig. 23 Gold belt buckles; 2nd century BCE; Width of plate, 13.3cm; Height of plate, 6cm; Length of pin, 3.3cm; Unearthed in 1994-1995 from the King's tomb at Shizishan This exhibition is a timely reminder that the research and study of the tombs of the kings of Chu continues to the present day. The privy on display (fig. 27) makes it clear that in the Han dynasty the needs of the dead were regarded as similar to the needs of the living, but this small niche documenting tomb "life" also highlights the fact that this exhibition is not archaeological in the information it provides, but art-historical in its emphasis on high-quality recovered objects rather than the visual documentation of an excavation and the archaeological work the recovery of these objects entailed. [BGD]  Fig. 24 Bronze tripods 2nd century BCE Height, 26cm, Diameter of belly, 31cm; Height, 24cm; Diameter of belly, 27.4cm Height, 21cm; Diameter of belly, 23.6cm; Height, 21.5cm; Diameter of belly, 20.3cm Height, 20cm; Diameter of belly, 19.8cm; Height, 16.2cm; Diameter of belly, 19cm Height, 16cm; Diameter of belly, 17cm Unearthed in 2005 from the pit at Yangguishan  Fig. 25 Gold belt hook 2nd century BCE Length, 3.5cm Unearthed in 1994-1995 from the king's tomb at Shizishan  Fig. 27 Stone latrine 2nd century BCE Unearthed in 1989-1990 from the queen's tomb at Tuolanshan  Fig. 26 Line drawing of Fig. 23 AcknowledgementsAlthough the National Museum of China permits visitors to the exhibition to photograph objects, in line with new museum policies in China, the illustrations here are taken with permission from the exhibition catalogue, Da Han Chu Wang, jointly compiled by the National Museum of China and the Xuzhou Museum and published by Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe, Beijing, 2005. References:Geng Jianjun, "Xuzhou Shizishan Xihan Chu wangmu kaizao shijian kaoxi" (A study on the date of the construction of the Western Han Prince of Chu's mausoleum at Shizishan in Xuzhou), Dongnan wenhua, 2000:3, pp.73-77. Meng Qiang and Qian Guoguang, "Xihan zaoqi Chuwang mu paixu ji muzhu de chubu yanjiu" (A preliminary study of the sequence and occupants of the early Western Han mausoleums of Chu kings), Xihan wenhua yanjiu (Studies on Western Han culture) no. 2, Wenhua Yishu Chubanshe, 1990. Nanjing Bowuyuan (Nanjing Museum), "Tongshan Xiaoguishan Xihan yadong mu" (The Western Han rock-cut tomb at Xiaoguishan in Tongshan), Wenwu, 1973:4. Nanjing Bowuyuan (Nanjing Museum), "Tongshan Xiaoguishan erhao Xihan yadong mu" (The no. 2 Western Han rock-cut tomb at Xiaoguishan in Tongshan), Kaogu xuebao, 1985:1. Excavation Team of the Shizishan Chu King's Tomb, "Xuzhou Shizishan Xihan Chu wangmu fajue jianbao" (A brief report on the excavation of the Western Han Chu king's tomb at Shizishan, Xuzhou), Wenwu, 1998:8. Wei Zheng, Li Huren and Zou Houben, "Xuzhou Shizishan Xihan mu de fajue yu shouhuo" (The finds from the excavation of the Western Han tomb at Shizishan, Xuzhou city), Kaogu, 1998:8. Xuzhou Museum, "Xuzhou Shizishan Han bingmayong keng diyici fajue jianbao" (The first excavation of the Han warrior and horse figurine pit at Shizishan hill, Xuzhou), Wenwu, 1986:12. Xuzhou Museum, "Xuzhou Beidongshan Xihan mu fajue jianbao" (Brief report on the excavation of the Western Han tomb at Beidongshan, Xuzhou), Wenwu, 1988:2. |